Núm. 22 (2022)

En febrero de 2002, Collin Powell dio una rueda de prensa de carácter más bien rutinario en la sala correspondiente de las Naciones Unidas, en la que analizaba el desarrollo de los últimos acontecimientos de la llamada Guerra de Golfo. En aquella sala se encuentra una copia autorizada del Guernica de Picasso, que, sin embargo, fue sutilmente velada antes de que comenzara la intervención del por entonces Secretario de Estado norteamericano, supuestamente, para no herir la sensibilidad de los telespectadores, que podían fácilmente asociar el lienzo con una simbología generalista en torno al sufrimiento de las víctimas de guerra.

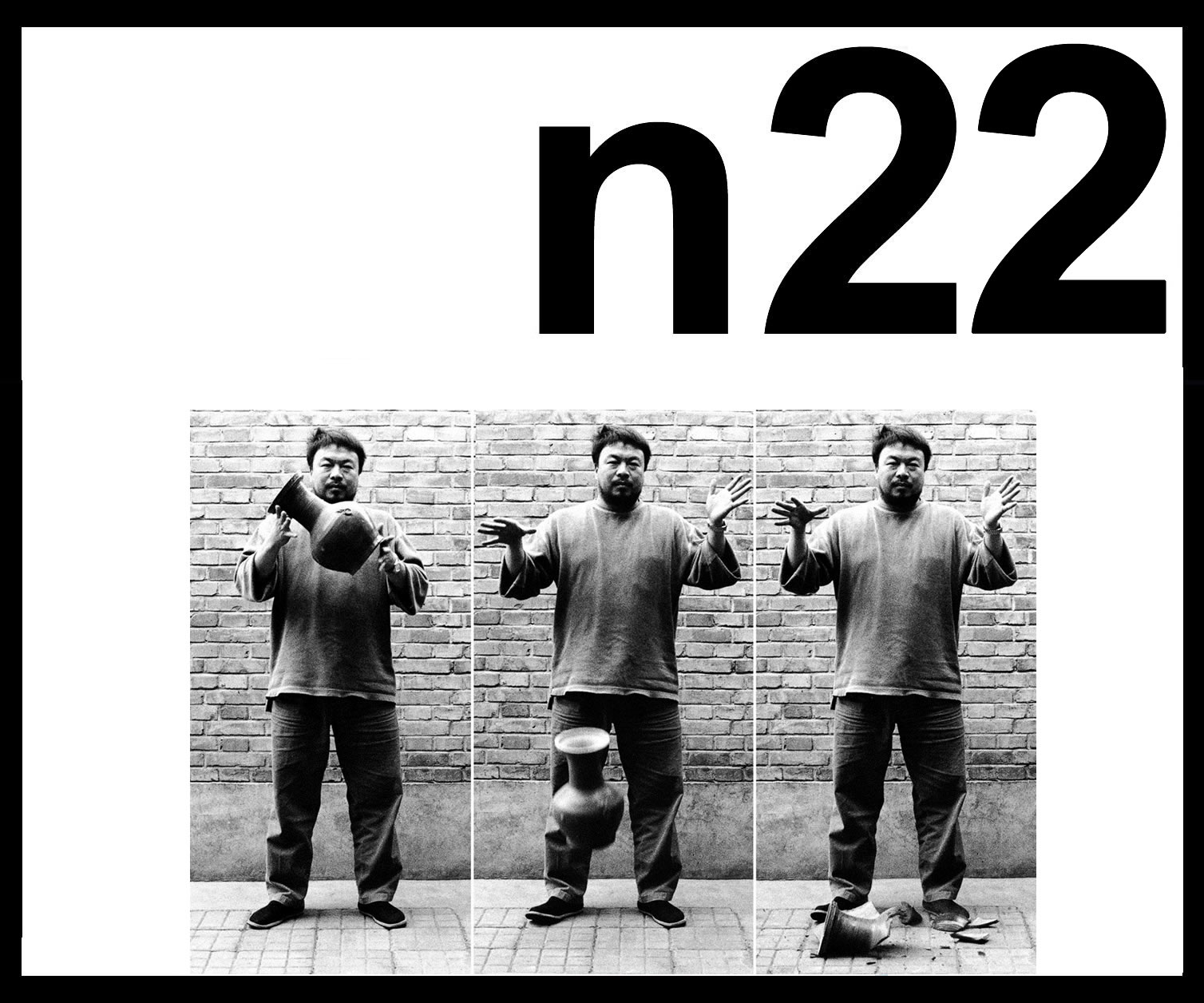

Destruir imágenes, ocultarlas, taparlas, disimularlas o, directamente, violarlas, ha constituido siempre un acto de poder blanco ejercido sobre la base de la violencia simbólica. Aunque históricamente, el fenómeno se ha asociado con la religión, teniendo en el Segundo Mandamiento del Decálogo uno de sus hitos históricos más determinantes y entablándose además desde entonces una clara vinculación entre iconoclasia e idolatría, no es ni mucho menos este el único ámbito en que el cabe encontrar gestos iconoclastas en la actualidad. La pregunta por la iconoclasia moderna conlleva preguntas ya formuladas en el pasado que parecen retornar por no haber sido aún resueltas: hasta qué punto la destrucción física de las imágenes supone la destrucción mental de sus significados. ¿Sigue siendo válida la distinción entre ídolo e icono, sobre la que se alzaron las justificaciones teóricas de la iconoclasia en la Antigüedad? Y quizás la pregunta por antonomasia que genera todo acto iconoclasta: ¿cómo es posible que una imagen pueda generar tanto odio y tanto dolor?

Desde el ámbito del arte, han surgido además nuevas formas de iconoclasia que amplían el ámbito de problematización. ¿No puede considerarse como iconoclasta la sombría reinterpretación que Bacon hizo del retrato de Inocencio X de Velázquez? ¿Y qué decir de las siete cuchilladas que soportó la Venus del espejo por parte de una sufragista canadiense en el año 1914? ¿Es la iconoclasia una forma de “politizar el arte”, como invitaba a hacer, frente a la estetización de la política, Walter Benjamin en La obra de arte en la época de su reproductibilidad técnica? ¿Fue la abstracción, como sugiere por su parte Gottfried Boehm, un acto iconoclasta dirigido contra la pintura figurativa? Y, puestos a generalizar, ¿no es la propia historia del pensamiento occidental, tan logocéntrico y volcado en textos, un ejercicio endémico de violencia contra las imágenes?

Fedro. Revista de estética y teoría de las artes invita a investigadores de ámbitos académicos vinculados a la filosofía y la estética a aportar una visión renovada de la iconoclasia, un fenómeno de ahora y de siempre, del que queremos explicar sus metamorfosis y derivas contemporáneas, así como proponer nuevos interrogantes que no permitan entenderla con una mirada más actual.

Fecha de entrega de los originales: 1 de marzo de 2022