http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/spal.2019.i28.05

Terra sigillata trade in Mesas do Castelinho (Almodôvar-Portugal): pattern of imports and contextual data in southern LusitaniaEl comercio de terra sigillata en Mesas do CASTELINHO (ALMODÔVAR-PORTUGAL): datos contextuales y patrones de importación en la Lusitania Meridional

Catarina Viegas

Universidade de Lisboa. UNIARQ – Centro de Arqueologia da Universidade de Lisboa,

Faculdade de Letras. Alameda da Universidade, 1600-214 Lisboa, Portugal.

Correo-e.: c.viegas@letras.ulisboa.pt.  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5434-2485

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5434-2485

Abstract: Mesas do Castelinho (Almodôvar) is located in southern Portugal, an area traditionally recognized as a natural path connecting coastal region in the Algarve and the inland Alentejo region. Occuppied since 5th century BC, the site is still relevant during the Roman Republican phase. After the Augustan reforms it progressively loses importance to be abandoned at the end of the 1st century AD. Terra sigillata, recovered in the project directed by C. Fabião and A. Guerra is abundant and forms a set of 322 pieces. Main categories are Eastern sigillata A, Italian-type, South Gaulish, Hispanic (from Andújar and Tritium) and Peñaflor type sigillata (“sigillata de imitación tipo Peñaflor”), ARS A and Phocean red slip ware. Following the economic dynamics of the site, the major phase of imports took place in Augustan-Tiberian period with progressive decrease until the end of the urban settlement in late 1st century AD. Episodic presence in the end of the 5th century AD is testified by one fragment of Phocaean red slip ware. The strategic position of Mesas do Castelinho determined its role during the Islamic period with fortress and settlement from the 9th-10th until the12th century, affecting and disturbing previous Early Roman phases.

Resumen: Mesas do Castelinho (Almodôvar) se encuentra en el sur de Portugal, una zona tradicionalmente reconocida como camino natural conectando la región costera del Algarve y el interior del Alentejo. Con ocupación desde el siglo V a.C., sigue siendo relevante durante la fase romana republicana. Después de las reformas de Augusto, pierde progresivamente importancia para ser abandonado en el final del siglo I d.C. La Terra sigillata recuperada en un proyecto dirigido por C. Fabião y A. Guerra es abundante formando un conjunto de 322 piezas. Las principales categorías son Sigillata oriental A, de tipo itálico, sur de la Gália, Hispanica (de Andújar y Tritio) y “sigillata de imitación tipo Peñaflor”, sigillata africana A e Foceense. Siguiendo la dinámica económica del sitio, la fase principal de las importaciones tuvo lugar en el período de Augusto-Tiberio con disminución progresiva hasta el final del asentamiento urbano a fines del siglo primero d.C. La presencia episódica está atestiguada en el final del siglo V d.C. por un fragmento de Foceense. La posición estratégica de Mesas de Castelinho determinó su papel durante el período islámico con una fortaleza y asentamiento desde el siglo IX-X hasta el XII afectando y perturbando la fase previa romana imperial.

Key words: tableware, consumption, commercial circuits, economy.

Palabras claves: cerámica, consumo, circuitos comerciales, economía.

1. Introduction

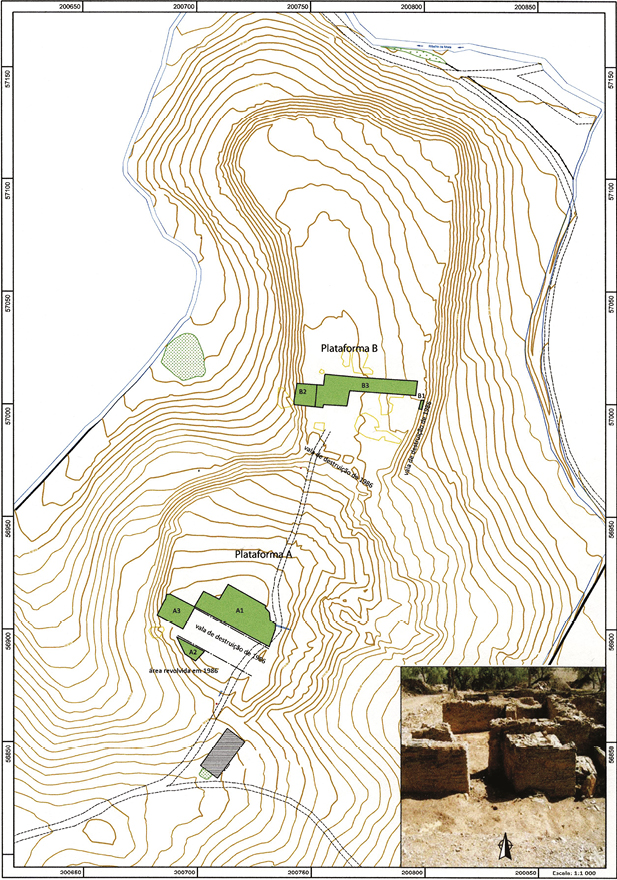

The site at Mesas do Castelinho (Almodôvar-Beja), is located in Southwest Iberian Peninsula – in the inland low Alentejo region - in an area that is considered to be the natural path or corridor through the montain (Serra do Caldeirão), connecting the coastal Algarve and the interior of Lower Alentejo region (fig. 1). This location might have been one of the major reasons for the establishment of the site, along with the mining resources, since there are no major agricultural resources known in the region.

Figure 1. Mesas do Castelinho in southern Lusitania (Fabião and Guerra 2010, modified).

More than two decades of the archaeological research project in Mesas do Castelinho allowed the identification of a significant amount of structures and materials from the different periods of its occupation. The research has been conducted by a team directed by C. Fabião and A. Guerra (UNIARQ, University of Lisbon) and besides the important scientific results that have been obtained, the site is under a conservation programme in order to allow visits by the general public (Fabião and Guerra 2010: 325-346).

The first occupation in Mesas do Castelinho dates from the Iron Age (5th century BC) and is a hilltop fortified settlement that from the 2nd century BC onwards entered the Roman sphere. Remodeling of the urban features was a reality during the Republican phase, but from the Augustan period onward the site progressively loses its importance possibly in favor of Arandis. This was considered the case of a “failed Roman town”, as the coordinators of the long-term research project have referred to, as the site was abandoned at the end of the 1st century AD (Fabião and Guerra 2010). After a long period without permanent occupation, the location was chosen to be an Islamic fortress and settlement, from the 9-10th to the 12th century (Guerra and Fabião 1993, 2002). This medieval Islamic presence has deeply affected and disturbed the previous early Roman layers.

In this paper we make a systematic analysis of the whole assemblage of terra sigillata from Mesas do Castelinho (plain and decorated forms; potters’ stamps). Imports took place from the last decades of the 1st century BC until the end of the Roman occupation of the site at the end of the 1st century AD, and originated from distinct areas of supply in Eastern Mediterranean, Italian Peninsula, Southern Gaul, Hispania and North Africa. Besides the identification of the pattern of imports and the dynamics of consumption in southern Portugal in this period and the comparison with other sites in the region, there is a particular focus on a rare, especially well-preserved context that was dated from the Late Augustan period.

2. General overview of Mesas do Castelinho during the Roman Republican and early Empire

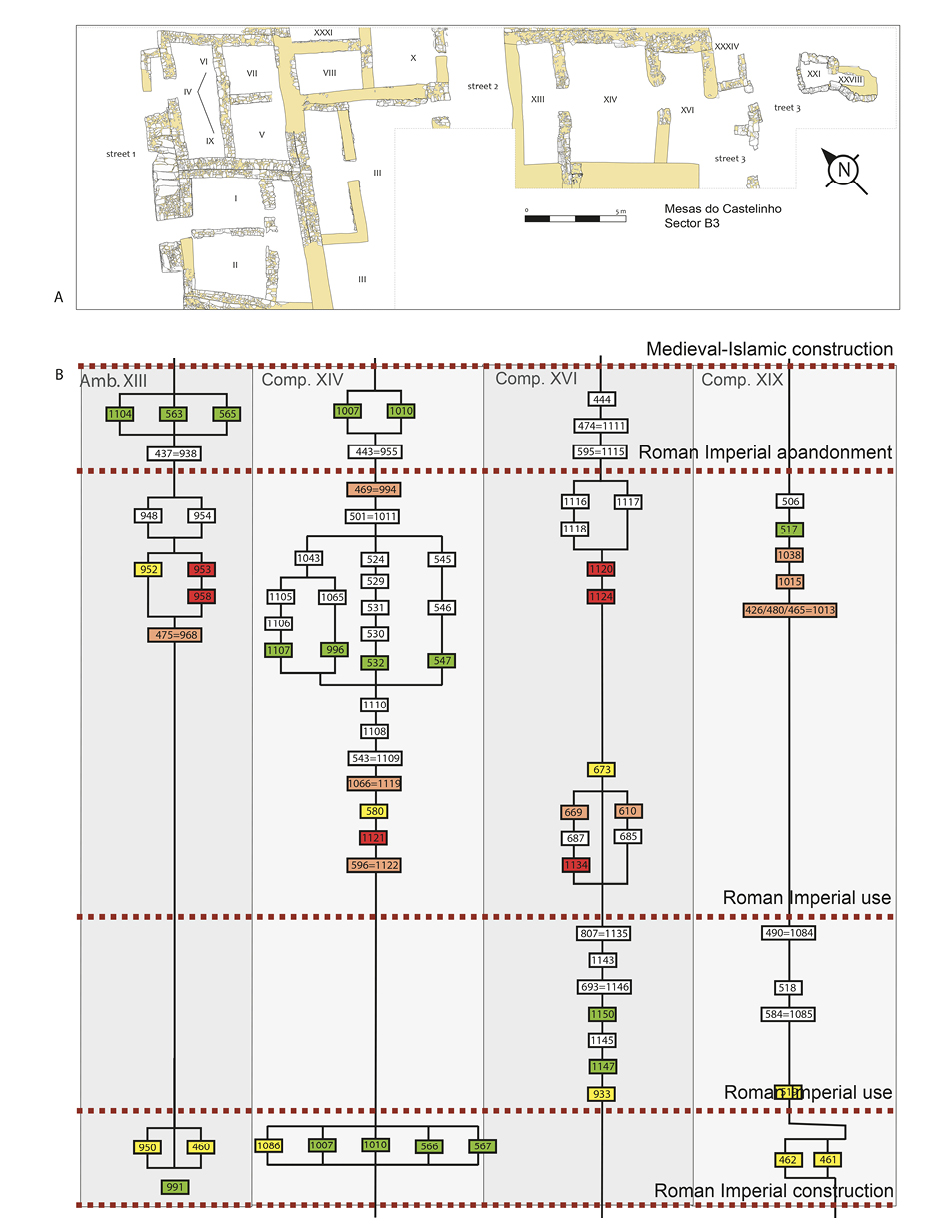

Considering both the quantity and quality of Campanian ware imported to Mesas do Castelinho, the site must have maintained its relevance as an urban center during the Roman Republican period. This is also the clear testimony of the full integration of this region in the main Roman supply network from the 2nd century BC onward, as C. Alves as already pointed (Alves 2010, 2014). This relevance is also materialized by a series of remodeling episodes of the urban landscape, mainly in sector B, which shows an urban layout structured by three main streets with several buildings and compartments (fig. 2).

Figure 2. The site of Mesas do Castelinho with the location of the different sectors (according to Fabião and Guerra 2008; Alves 2010).

Preliminary information on the numismatic finds in the site show the presence of regional mints from both the town of Myrtilis (today Mértola) in the Guadiana river and Ossonoba (Faro) in the Algarve region (personal information from C. Fabião and A. Guerra, based on the “Preliminary report on the numismatic finds”) (fig. 1). The presence of both coins and lead tesserae is a clear evidence of the strong connection that was established with the southern coastal region and the Guadiana river (Fabião and Guerra 2010: 340).

The Early Imperial presence in the site is also a reality that can be perceived by the archaeological materials present in surface layers in the whole extension of the site and is particularly relevant in B3 sector. Here, as will be seen, there is a series of contextual data related to the remodeling of previous Republican buildings, during early Roman Empire.

3. Terra sigillata in Mesas do Castelinho: General pattern of imports

Terra sigillata recovered in the site is the result of more than twenty years of archaeological campaigns, since the first campaigns took place in 1989. The assemblage is formed by 445 fragments and 323 MNV and although it is highly fragmentary it allows the identification of different forms and their proveniences.

The systematic analysis of terra sigillata recovered in Mesas do Castelinho (tab. 1) allowed the identification of the imports pattern of the site and the comparison to other sites in the region, and made possible to understand, in some extent, the supply network where the site was integrated during Roman imperial period. Quantification method used to obtain the Minimum Number of Vessels was based on the Seville Protocol (pcrs/14) (Adroher et al. 2016).

Table 1. Terra sigillata recovered in Mesas do Castelinho.

|

Fragments |

% Fragments |

Minimum |

% Minimum Number of Vessels |

|

|

Eastern sigillata A |

3 |

0.69 |

3 |

0.93 |

|

Italian terra sigillata |

204 |

46.90 |

154 |

47.67 |

|

South Gaulish sigillata |

140 |

32.18 |

102 |

31.58 |

|

Hispanic sigillata |

86 |

19.77 |

62 |

19.20 |

|

ARS A |

1 |

0.23 |

1 |

0.31 |

|

Late Phocaean red slip ware |

1 |

0.23 |

1 |

0.31 |

|

Total |

445 |

100.00 |

323 |

100.00 |

Chronological scope of the terra sigillata in the site covers the periods between Augustus reign until the end of the 1st century AD and the main categories of terra sigillata that were in circulation in that period in Lusitania are represented: Eastern sigillata A (ESA); Italian-type sigillata (ITS); South Gaulish sigillata (SGS) mainly from La Graufesenque and Hispanic sigillata (HS) from either Baetica (Andújar) or Tarraconensis (Tritium workshops) and also the Peñaflor type productions (“sigillata de imitación tipo Peñaflor”). Besides terra sigillata, this general chronology is also supported by the other categories of ceramics that have been partially studied (e.g. amphorae) (Parreira 2009), as well as the numismatic findings in the site.

The presence of ESA is testified by few fragments that don’t allow the identification of the forms and consequently, its precise chronology is difficult to establish. Despite this and considering the other sites in Lusitania where ESA was recovered, a Late Republican chronology is a strong possibility and so this fragments could be contemporary of the major Campanian imports to the site (Alves 2010, 2014).

ITS is the most abundant sigillata in the site (47.67%) showing that its population still had a relevant purchasing capacity during the Augustan/Tiberian period. From that moment onward the relatively smaller proportion of SGS and HS (31.58% and 19.2%, respectively) are a clear testimony that the site was progressively losing its previous relevance.

One fragment of ARS A form Hayes 9A recovered in the surface layers may extend the chronology until the early 2nd century AD but the lack of precise context leads us to view these data with some caution. On the contrary, we know that the only example of Late Phocaean Red Slip ware (Late Roman C) form Hayes 3D, which is dated from the third quarter of the 5th century (Hayes 1972: 336-337), is originated in a context, stratigraphic unit (SU) [17] that was identified as a small trench “dug” in the upper layers that covered the Republican building in sector B2 (fig. 11, nr. 112). In this case, it is clear that this is an episodic presence in a site that had been abandoned for quite a long period of time and that will only be occupied once again in the 9-10th century, in the medieval Islamic period.

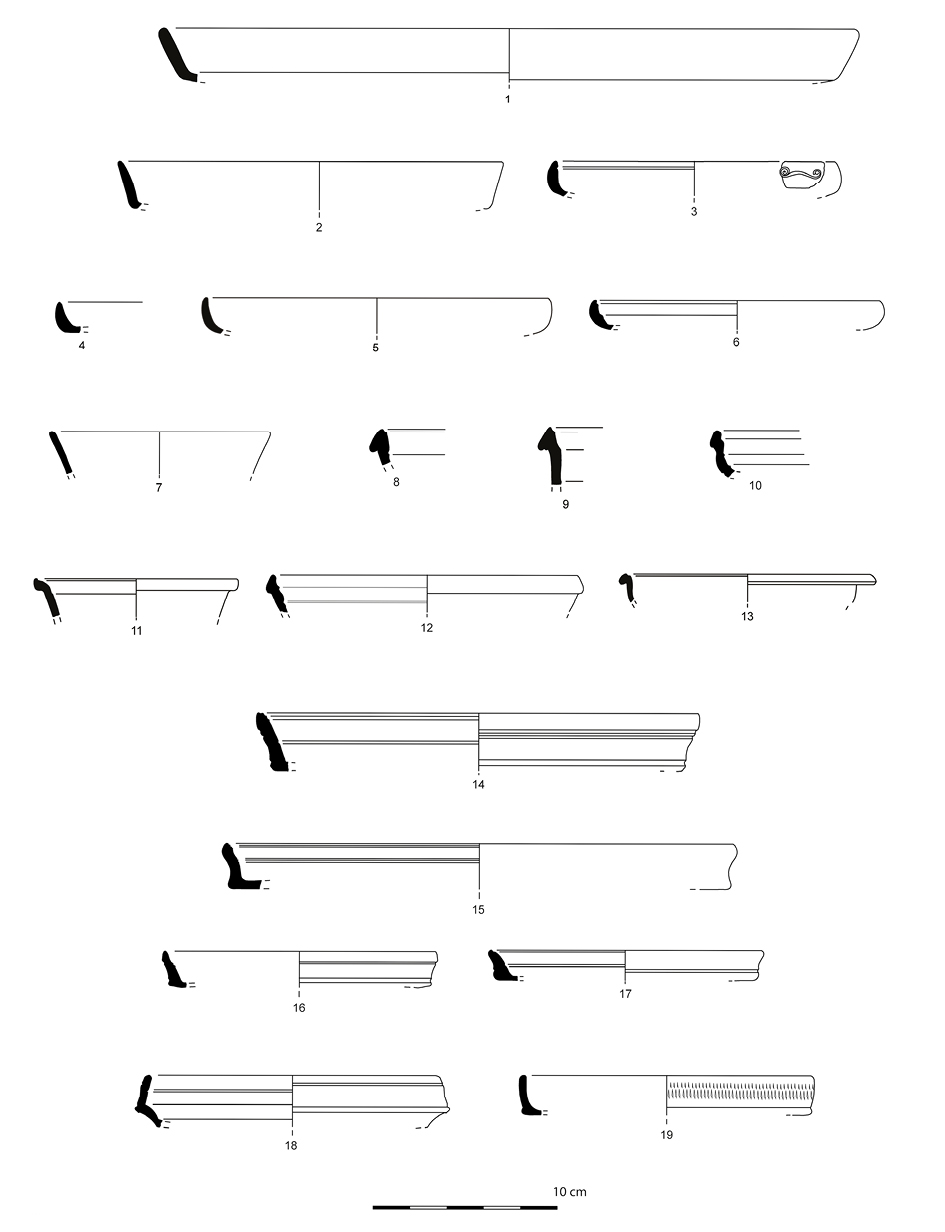

3.1. Italian sigillata

Concerning the terra sigillata assemblage, ITS is the most frequent in Mesas do Castelinho and the chronological scope of the imports show that it covers the period between the last decade of the 1st century BC until the second half of the 1st century AD (tab. 2 and figs. 3 to 5). A quite timid beginning of the supply must have started in the last decades of the 1st century BC, as could be testified by few examples of the plate Consp. 1 (fig. 3, no. 1-2), the cup Consp. 7.1 (fig 3, no. 7) or even the cups Consp. 13.3 (fig. 3, no. 11) and 14.1 (fig. 3, no. 12). Accordingly, the radial stamp of Ateius (OCK 267.26) (fig. 5, no. 36) should also integrate this first moment of Italian imports to the site. In this context, it must also be remembered that black Arretine sigillata had already been identified with the stamp of the Arretine potter Q.AF (Alves 2010: Est. XXI, nr. 3430; 2014: fig. 5, nr. 31). These early ITS suggests that there was some degree of continuity between black gloss Campanian ware and ITS imports.

Table 1. Terra sigillata recovered in Mesas do Castelinho.

|

Fragments |

% Fragments |

Minimum |

% Minimum Number of Vessels |

|

|

Eastern sigillata A |

3 |

0.69 |

3 |

0.93 |

|

Italian terra sigillata |

204 |

46.90 |

154 |

47.67 |

|

South Gaulish sigillata |

140 |

32.18 |

102 |

31.58 |

|

Hispanic sigillata |

86 |

19.77 |

62 |

19.20 |

|

ARS A |

1 |

0.23 |

1 |

0.31 |

|

Late Phocaean red slip ware |

1 |

0.23 |

1 |

0.31 |

|

Total |

445 |

100.00 |

323 |

100.00 |

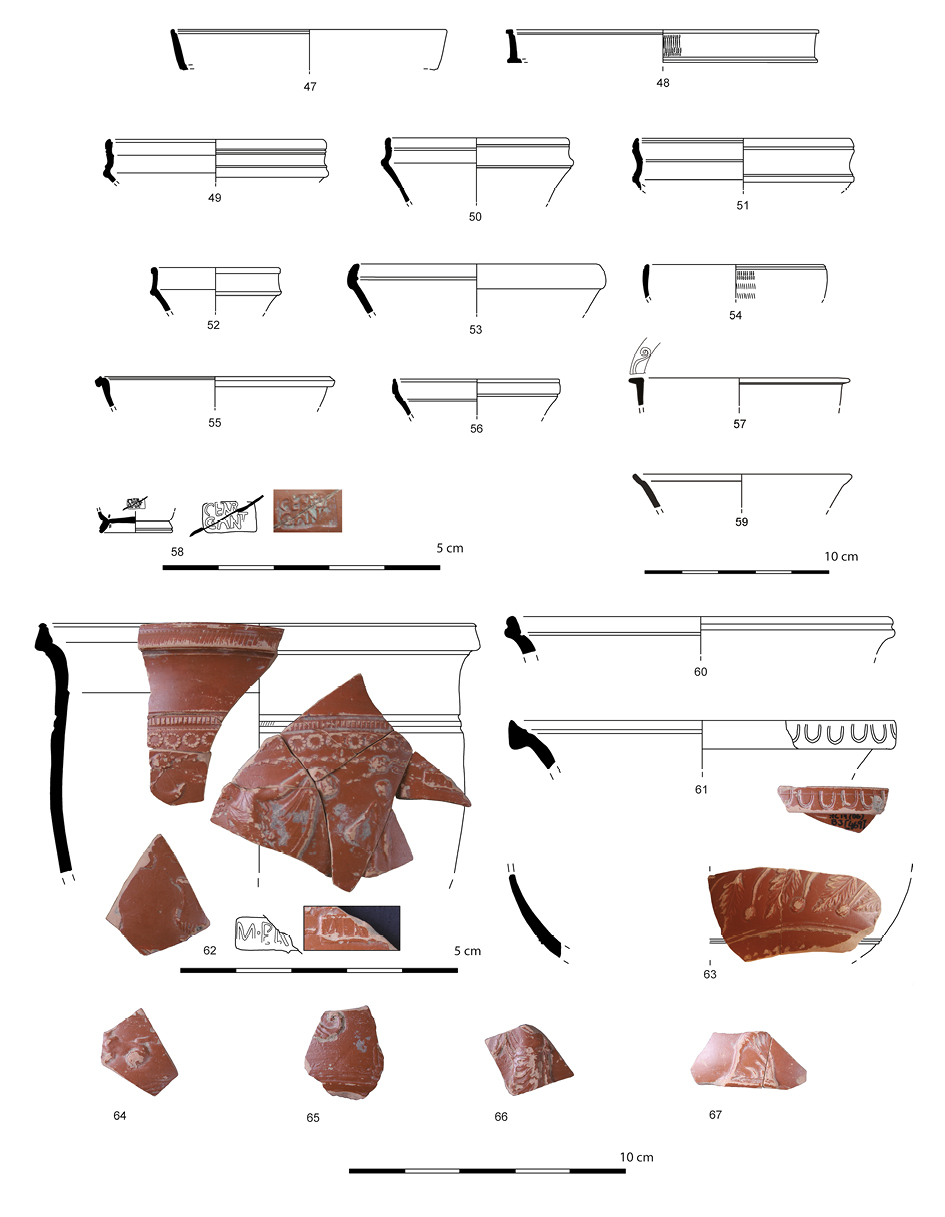

Most of the Italian-type sigillata imports must have taken place during the middle to the end of the Augustus reign, which is the period of major diffusion of Italian-type sigillata, as the distribution of forms show (tab. 2, fig. 3-5). The diversity of forms is to be highlighted and the most frequent types of this period are the plates Consp. 4.4-4.6 (fig. 3, no. 3-6), Consp. 12.4 (fig. 3, no. 10), Consp. 18, 18.2 (fig. 3, no. 14-17), Consp. 20.1-3 (fig. 3, no. 19; fig. 4, no. 20-23) and the cups of the types Consp. 22.1 (fig. 7, no. 49-51) and Consp. 22.6 (fig. 7, no. 52). Decorated chalices type R 2.1 (fig. 7, no. 61), R 4.2 (fig. 7, no. 62) and broad beaker R 11.1 (fig. 7, no. 63), are also dated from this period (Mid to Late Augustan). Late Augustan imports are particularly well represented, as will be seen infra, in the specific context that was retrieved in sector B3, in a sequence of use and remodeling of the Roman urban layout (fig. 6 and 7).

Figure 3. Italian terra sigillata from Mesas do Castelinho.

Figure 4. Italian terra sigillata from Mesas do Castelinho.

ITS was still in circulation in the first half of the 1st century AD but in a smaller proportion, represented by the later forms such as Consp. 26.1 (fig. 4, no. 25), Consp. 27.1 (fig. 4, no. 26), 32.2 (fig. 4, no. 27), 33.1 (fig. 7, no. 54), to mention a few examples. The frequency of the plate Consp. 20.4, but also the presence of forms Consp. 36.4 and 37.3 with a chronology that could be extended to the second half of the 1st century, are a clear testimony of the consumption of these products in the site in a later phase of the Italian production. In fact, in this period the site must have already changed its sources of supply, obtaining products from the South Gaulish centers, namely from La Graufesenque.

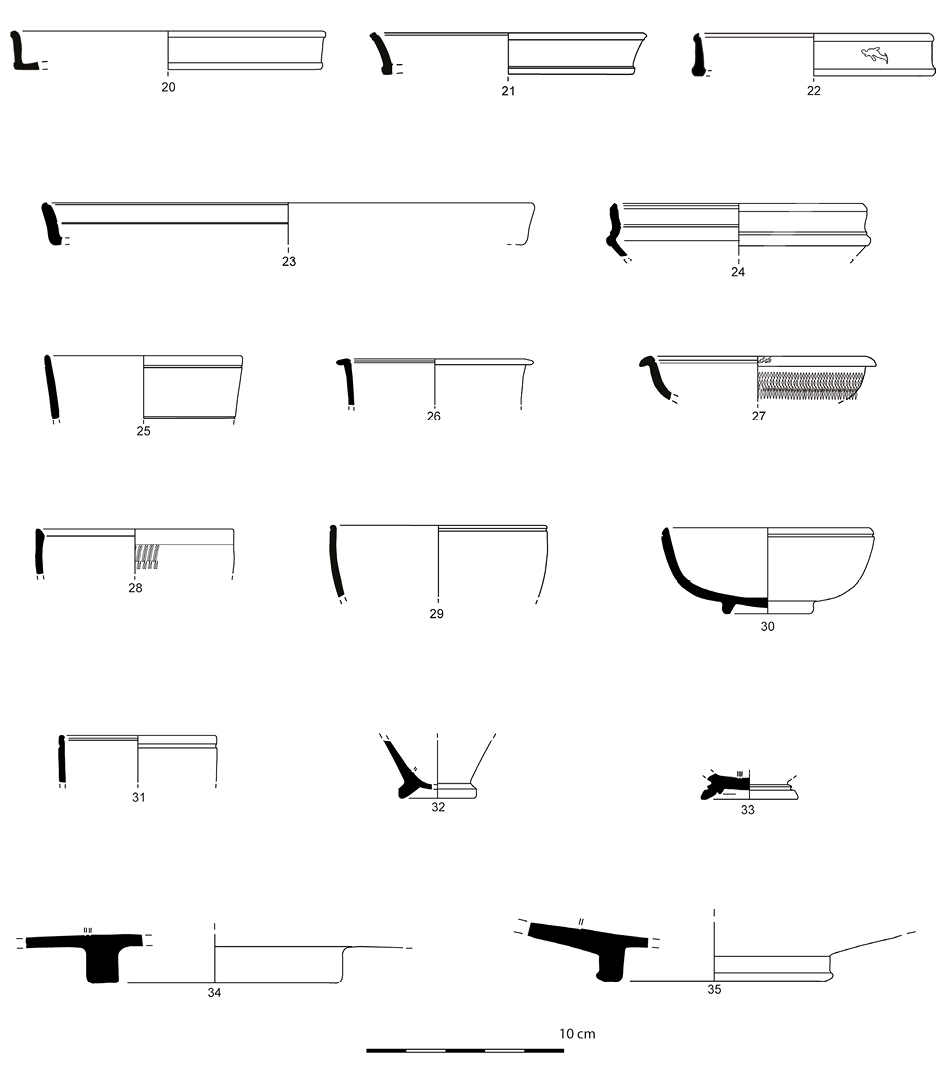

There are eleven ITS potter’s stamps, and from the eight that could be read, the chronology of the majority is situated in the period between 15 BC until 20 AD, with one earlier example dated from 40 to 20 BC and another quite later piece attributed to 1-40 AD (fig. 5 and tab. 6). Main areas of supply were Arezzo, though Central Italy and Pisa were also responsible for the exportation to the site, as determined by the potters stamps. The majority have their origin in the Arretine workshops as is the case for the radial stamp belonging to Q.AF (OCK51.1) in black sigillata, dated from 40 to 20 BC, which was previously published (Alves 2010: Est. XXI, nr. 3430; 2014: fig. 5, nr. 31). The ATEIVS (2) workshop is represented also by the radial stamp (OCK 267.26) (fig. 5, no. 36) dated from the 15 to 5 BC. Unfortunately, the only letters that were preserved are the final part of the stamp EI, marked on the bottom of a plate (Consp. B 1.3). Despite beeing a 7mm in planta pedis stamp with a tenuous dye, we believe that the stamp in the base of a possible Consp. 28 (fig. 5, no. 37) can be attributed to ATEIVS (3) (OCK 268) from Pisa, who has labored from 5 BC until AD 25. The only letters we could identify is the A and an incomplete part of a T but the similarity with OCK 268.140 is strong and favors our proposition.

Figure 5. Italian terra sigillata from Mesas do Castelinho. Potters stamps and grafitti.

Two different stamps of M. PERENNIVS are known in Mesas, one in a plain form (base of cup Consp. B 3.9 (OCK1391.44) (fig. 5, no. 39) and the other in an incomplete though readable intradecorative stamp in a R 4.2 chalice (OCK1390.4) (fig. 7, no. 62). We will discuss the details of the context and the decoration of the Dyonisiac cycle of this vessel, further below. Also from Arezzo, one of the stamps identified belong to the production of C.ANNIVS, slave GEMELLVS (OCK147.2) (fig. 7, no. 58), that is dated from 15 BC onwards; and C.VIBIENVS (OCK2373.66) (fig. 5, no. 40), that produced in the first half of the 1st century AD. Two potter stamps are more difficult to read due to a weak impression of one of the stamps (fig. 5, no. 38), and because it was poorly preserved, in the other case (fig. 5, no. 41). We think that the stamps with C.PA?/PAR, that could be attributed to C.PA(IDEIVS)PAR( ) (OCK1367.2) (fig. 5, no. 38), with a production dating from 15BC until 5AD possibly from central Italy (?). In the second case (fig. 5, no. 41), in the two-line stamp, we can read O and what can be part of a P or R at the beginning of the first line and in the second line: C.ANN. Considering that the stamp is incomplete and that none of the C. ANNIVS potter stamps have an association with a slave name starting with O (Orbius ?), we may propose this could be another slave of the Arretine potter C.ANNIVS. Another possibility could be C. Annius, slave Cerdo (OCK 137), but none of the known dyes present the name Cerdo in retrograde.

Unfortunately the internal stamps in fig 5, no. 42 is incomplete and the only thing we could read was the upper part of a possible C and V (?), also internal in planta pedis stamp in the base of Consp. 33 (fig. 5, no. 43) the same situation happens allowing only to read what seems to be the upper part of C, F ou E and A (?). Internal stamp in the base of an undetermined cup only shows the final letter I in rectangular stamp-frame with a bifid end (fig. 5, nr. 44).

We were able to make some further considerations on the distribution of Italian sigillata stamps based on the data in the OCK (Oxé, Comfort and Kenrick 2000) (available in the Samian Research database: https://www1.rgzm.de/samian), with more updated information for Portugal, seeking to understand the circulation of this products. I was particularly interested in recognizing the dissemination of the different potters for the western provinces, particularly for Hispania, but also the Mauritania Tingitana.

The distribution of Q.AF stamp is quite restricted and only seven stamps are known outside of Italy. Considering the distribution to the western provinces, it was already referenced in Sala (Marrocco) and Ampurias (Spain). To our knowledge, it is the first time that the stamp of C. Annius, slave Gemellus (OCK 147) is identified in Hispania, in this occurrence in Mesas do Castelinho, as the potter has a limited distribution with only seven occurrences.

Naturally, the potter ATEIVS (2) (OCK 267) has more than 400 examples in OCK database although most of them are from Arezzo. Its production was mainly destined to Germany and France, but there are also five pieces identified in Spain (Ampurias, Ibiza, Varea and Mérida) and two in Morocco (Lixus and Mogador). Concerning the diffusion of ATEIVS (3) from Pisa, this is not so easy to determine since most of the Ateius stamps have been generally attributed to Ateius workshops in Arezzo.

Distribution of M. Perennius (OCK1391) with 153 examples in OCK database, is quite wide. Apart from Italy (with 55 stamps), its products spread both in east and western Mediterranean. In the western provinces, there are two pieces identified in Marroco (Lixus and Sala) and seven in Spain (Alicante, Ampurias, Ibiza, Mérida and Tarragona). In Portugal this potter was already known in Alcácer do Sal (Dias 1978: 145-154, especially nr. 4, 148) and also in Represas (Beja)(Ribeiro 1958: nr. 75; Silva 2012; Lopes 1994). Intradecorative stamp of M. Perennius is not so well distributed as the previous one; nevertheless 105 examples are known, with several stamps in Spain (Cartagena, Elda, Herrera de Pisuerga, Lleida, Pollentia, Tarragona, Varea). It is the first time that this potter is identified in an intradecorative stamp in Portugal.

Potter C. Paci(deius) Par had a relatively restricted diffusion and only 6 examples are known in OCK database, distributed in Italy and in Spain (Ampurias and Tarragona). The stamp in Mesas do Castelinho is not completely clear but if confirmed is the first one in Lusitania. C. Vibienus is an Arretine potter with a wide distribution with over 190 examples in OCK database. His stamps are known in Marroco (8), (Sala and Lixus), in Spain (23 stamps from Ampurias, Cartagena, Cordova, Elche, Ercavica, Numancia, Segobriga, Sevilha, Tarragona and Valeria). His distribution in today Portugal is also well established with several examples in southern Portugal in Balsa (Torre de Ares, Tavira) (two examples) (Nolen 1994: 66, si-14, Est. 10, fig. 20; Viegas 2011: 293-294, nr. 556, est. 39.), Castro Marim (Viegas 2011: est. 84, nr. 1049), Milreu (Teichner 2008: F6, Tafel 128), Alcácer do Sal (Faria et al. 1987: nr. 21), Miróbriga (Quaresma 2012: 83, nr. 25) and Represas (Beja) (Lopes 1994: nr. 1626 and 1640, Quadro I).

Considering the origin of the Italian sigillata potters in Mesas do Castelinho, apart from the uncertain central Italian (?) C. Paci(deius) Par, and the possible Pisa Ateuis, there is a clear dominance of the Arretine workshops, that distributed their production mainly in the first two decades BC until the change of the era. Black sigillata with the potter stamp of Q. Af escape this trend, being much earlier, as well as the C.Vibienus in this case because it is a stamp that is situated, from a chronological point of view, in a later phase in the first decades of the 1st century AD.

Grafitos occur in three ITS pieces though in one case it is particularly poorly preserved (fig. 5, no. 43), the only visible letters are CA. In another quite interesting piece it was possible to read the letters MA in the exterior base of a cup (unfortunately potters stamp is truncated and illegible) (fig. 5, no. 45). What is most curious about this fragment is that a close observation has led not only to the identification of these letters (written in a nexus), which possibly corresponds to the abbreviation of a name but also to what we believe to be a subsequent action to scratch out the name making it almost imperceptible. The purpose must have been to delete the name. As graffiti are associated with names of owners, this could be the case of misappropriation of this cup by someone else. The second piece with a graffito in the assemblage poses a totally different set of questions. In the interior base of a cup where part of the slip has disapeared, it was possible to identify some geometric signs and possible letters that are very difficult to interpret (fig. 5, no. 46). In the center of the piece there is an X inside a circle and, disposed radially, there are a series of V, F and square shape symbols limited by two concentric circles. We weren’t able to find any other example similar to this one and unfortunately the context where it was found in B2 sector [147] does not elucidate further on this matter. The piece is originated in the floor level of a compartment belonging to Imperial phase in the site B2 sector [147] (fig. 5, no. 46). Other aspects should be mentioned because if grafitti are usually seen as signs of property, normally they are positioned in the exterior part of the vessels, which makes this a quite unique example. Another possibility is that it was used, as a decorated base with a different function from its original one that we cannot identify, though a game piece could be proposed.

Previously, in the Republican period, in the assemblage of Campanian ware, it was also possible to identify five pieces bearing graffiti (Alves 2010: 80-81). The author distinguished, from a set of incisions with no apparent logic, some examples where could be seen letters, such as A or X.

A close observation of the ITS distribution over a wider geographical area in Southern Portugal emphasizes what seems to be a trend of the supply from the Arretine workshops. In fact, in the assemblage composed of eleven Italian potter stamps from the site at Castelo das Guerras (Moura) (Caeiro 1976-77: 419-422) there is a similar pattern when comparing the origin of the potters, also with a clear predominance of Arezzo, though with some examples from Pozuoles and Pisa. When comparing the chronology of the potter’s stamps from Castelo das Guerras with those from Mesas do Castelinho, most of them point to the last decades of the 1st century BC and the first decade of the 1st century AD which is slightly later than the ones in Mesas. Only three potters stamps allow extending the chronology until the first half of the 1st century AD (40 AD).

Also, an important site for comparison, Castelo de Manuel Galo (Mértola) (Maia 1974: 157-174; Maia 1987) is a Roman site near Mértola where a relevant amount of terra sigillata has been recovered. PhD project by C. Alves will surely bring new light into this and other related sites (Alves 2014: 385-403). In fact, ITS potter stamps retrieved in the seventies of the 20th century - ten pieces - show that the sources of supply to this site were primarily the Arretine workshops with a few examples from the Po valley and Pisa. Despite the presence of one radial stamp, there is a larger number of pieces that are attributed to the first half of the 1st century AD, than the ones in Mesas do Castelinho and Castelo das Guerras.

Early Italian-type sigillata imports are a reality in other inland Alentejo sites, such as Caladinho (Mataloto et al. 2014: 17-43), and Castelo da Lousa (Carvalho and Morais 2010: 139-151). In fact, in these sites, the chronology of the ITS forms and potter stamps does not extend beyond the turn of the era, as we witness their abandonment. Although in most places of today Portugal the service II of Haltern is dominant, in these Alentejo region sites it is the service I of Haltern that is the most numerous. According to R. Mataloto, J. Williams and C. Roque proposal, these sites and others located in Upper Alentejo region are part of a network of settlement previous to Roman times, which corresponds to the initial stages of the formation of the province of Lusitania (Mataloto et al. 2014: 17-43). Their military character is attested by the location, the architectural features (often with walls and associated towers), as well as the recovered materials.

Despite being quite rare, distribution of the radial stamps in this region of the former Roman province of Lusitania allows the identification of the circuits of supply in a quite early moment of the commercialization of Italian-type sigillata. The participation of the region of Mesas do Castelinho in this circuit, show that an area that is quite far from the coast, must have had a population with, simultaneously, a taste for Italian-type sigillata (imported tableware) and the capacity for its acquisition. Land routes must have played an important role in this context, combined with riverborne trade.

Consumption of Italian-type sigillata in the above-mentioned sites also arise questions about the civil versus military supply. In fact, the commercialization of this tableware in Mesas do Castelinho is done in a clear civil context. This aspect must also be valorized as the consumption of Italian sigillata is often related with socio-cultural change that took place in the different provinces of the empire.

Decorated vessels usually represent a tiny proportion of the total assemblage and Mesas do Castelinho follows this general trend. In fact, considering the MNV, there is a percentage of 7.6% of ITS decorated pieces which is a relatively higher proportion when compared to Represas (Beja) where they are 6,9%, and Conimbriga with only 5%.

In most of the fragments it is only possible to observe a small portion of the decoration such as parts of human figures, or the line of ovolo. One of the most interesting and most well preserved pieces in this assemblage is the chalice with the Dionysiac cycle that has the intradecorative stamp of the Arretine potter M.Perenius (fig. 7, no. 62). In this piece we were able to identify the motif of the menade in profile with a robe and a thyrsus in one hand, which is similar to the punction M li 10a in Porten Palange (2004: 130, Tafel 63); in other fragments we can see the statue of Dyonisus in a second plan, holding a bunch of grapes in one hand and a thyrsus in the other, and the closest punction corresponds to mStHe fr 3s in Porten Palange (2004: 317, Tafel 170, 317). The motif of a cantharus and the figure of a felidae could also be part of the same cycle and are attributed to the work of M. Perennius, as the figure of a panter (?) is similar to the punction T/Felidae li 9a in Porten Palange (2004: 271, Tafel 152), but unfortunately these fragments couldn’t be integrated into the mentioned chalice.

In some other chalices, the rims of form R 4.2.1 and R 2.1 (fig. 6, no. 60 and 61 respectively) were identified, though the dimension of the fragment does not allow the identification of the motifs of the decoration. The latter piece is, however, quite peculiar because it has a line of impressed double ovolo in the outer face of the rim. This rare form of decoration was previously identified among the material from the excavations in the Duomo Cathedral in Florence published by J. Bird (2013: 289-305, especially nr, 49). As is pointed by the author, the Italian example could have belonged to a chalice or a Modiolus of the Tiberian or Tiberian–Claudian period. Considering that our chalice belongs to a context that was dated from the Late Augustan period, we propose an earlier chronology. The impressed ovolos with or without tongues are present in the exterior surface of hanging lips in ESA plates Hayes 9 and 11, dating from the pre-Augustan period (50-25 BC)(Hayes 1985: 18-19, Tav. II). Examples of these ESA forms are rare in Portugal but have been identified in Santarém (Viegas 2003: 37) and in Alcácer do Sal (Sepúlveda et al. 2013) 371- 409). The same decoration is also present in large platters from a production context (Celsa furnaces) in Rome (Carrara 2012: 1-27, especially the plate with the catalog nr. 6.). In both cases, it seems that the prototypes are to be found in metal examples, as M. Carrara refers (ibd). Following what has been said, we believe that the line of impressed ovolo in the ITS chalice corresponds to another testimony of the interaction between Eastern and Italic potters at the beginning of the imperial era.

In another decorated piece in Mesas do Castelinho, possibly belonging to a chalice, only the lower part of the vessel is conserved with the decoration of floral motifs (fig. 7, no. 63), possibly attributed to the work of Bagarthes (Dragendorff and Watzinger 1948). Among the decorated pieces there is a small fragment of a base with a portion of decoration that was classified as a possible broad beaker of form Consp. R 11.1.1 which is mid to late dated from Augustan period (Ettlinger et al. 1990: 180). Despite the assemblage being highly fragmentary, it seems once again, that the Arretine workshops are predominant. Even though decorated pieces are always a minority in the assemblages of Italian-type sigillata, among the different motifs that Italian decorated pieces bear, Dyonisiac scenes are quite well represented in Portuguese sites (Sepúlveda and Fernandes 2012: 139–154).

3.1.1. Contextual data for Italian-type sigillata in Mesas do Castelinho

Apart from this general overview seen by the chronological evolution of ITS imports in the site, we also focused on specific stratigraphic data that was recovered which allows considerations on the way ITS was used/consumed in this particular urban centrer. In fact, during the 2006 and 2012 campaigns it was possible to detect, in the B3 sector, several homogenous stratigraphic units (SU) that were interpreted as the remains of primary contexts of use with several pieces of Italian sigillata associated to the Early Empire remodelling of the urban features (Fabião et al. 2006; 2012; 2013) (fig. 6, tab. 3). The abandonment levels were also identified in this area where the medieval islamic presence was also noted.

Figure 6. A. Final plan of Sector B3 in Mesas do Castelinho. B. Stratigraphic diagram of the sequence of the occupation in Sector B3: Compartments XIII, XIV, XVI and XIX (according to Fabião et al. 2012, modified).

Despite terra sigillata being recovered in every campaign of excavation, it was only in 2006 that began to be possible to delineate more clearly the characteristics of the early imperial Roman occupation of the site. In fact, in the 2006 campaign, the continuation of the excavation in sector B2 and B3 showed several Roman Republican urban features formed by streets and buildings with several compartments (fig. 2 and 6). In the later Imperial occupations that produced some transformations in the previous urban layout, particularly in B3 sector, it was possible to recover homogenous archaeological levels of the early imperial period (Fabião et al. 2006). In these layers, that correspond to the cycles of remodeling/use and abandonment of a series of compartments (comp. XIV, XVI and XIX), the researchers that conducted the excavations were able to identify layers with a relevant assemblage of Italian-type sigillata. In this context, we would like to particularly highlight the sequence recovered in compartment XIV where it was possible to identify an assemblage that can be assigned to the actual occupation and use of the compartment (Fabião et al. 2006) (fig. 6).

Table 3. Italian terra sigillata from the context in sector B3, compartment XIV.

|

Sector B3 |

CompartmentXIV |

Context: SU [469=1011] [501] |

|

|

Frags |

MNV |

||

|

ITS |

Consp. 4.4 |

5 |

1 |

|

plain |

Consp. 4.5 |

1 |

1 |

|

Consp. 12.1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 12.5 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 14.4 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 15.1 |

4 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 18.5 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 20 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 20.1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 20.3 |

5 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 22.1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 22.2 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 22.3 |

4 |

4 |

|

|

Consp. 22.5 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Consp. 22.6 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 24.1 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 33.1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Consp. 37.3 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Undeterm. |

13 |

8 |

|

|

decor |

Chalice R 2.1/stamp |

2 |

1 |

|

Chalice R 4.2 |

12 |

2 |

|

|

Consp. R 11.1. |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Calice indet |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Decor indet |

8 |

2 |

|

|

Total |

72 |

36 |

|

|

GEMELI/C·ANNI OCK 147.2 |

1 |

– |

|

|

Peñaflor |

Martínez Ia |

1 |

1 |

|

SGS |

Drag. 18 |

2 |

1 |

In this context (specifically in the SU [469=994] and [501=1011]) 71 fragments of Italian-type sigillata were recovered belonging to 36 pieces (tab. 3, fig. 6 and 7). The plain forms identified were the plates Consp. 4.4, 4.5, 12.5, 18.5, 20.1, 20.3, and cups Consp. 22.3, 22.5, 22.6, 24.1 and 33.1 and the decorated pieces of chalices of the forms R 2.1 and R 4.2.1. As said before, decoration in most of these pieces was poorly preserved but we were able to identify a Dionysiac scene belonging to the work of M. Perennius (in an intradecorative potters’ stamp). Another chalice had a rare decoration formed by a line of impressed ovulo in the exterior part of the rim, as mentioned above. Among the decorated pieces, a small fragment of a base of a broad beaker Consp. R 11.1.1 was also identified. Another potter stamp in a plain cup was attributed to the Arretine C. Annius, slave Gemellus, that worked from 15 BC onward (OCK 147.2) (fig. 7, no. 58).

Figure 7. Italian sigillata and Peñaflor type sigillata from the Late Augustan context in sector B3 (plain forms, decorated and potters’ stamps).

In a clear association in this context, there is also one fragment of Peñaflor type sigillata (“sigillata de imitación tipo Peñaflor”) form Martínez Ia (fig. 7, no. 59), (or Amores and Keay type 14) (Amores and Keay 1999: 231-252). Referring to the Martínez typology we can stress that this form, which was inspired in ITS form Consp. 8 should be dated from the end of the 1st century BC and Augustus-Tiberian period according to the contexts in Itálica and Écija (Amores and Keay 1999: 236) and also because of its Italian prototype.

Most of the Italian-type sigillata in this context has strong affinities to those in the contexts identified in northern Gaul as Late Augustan and early Tiberian (Hanut 2004: 153-203, fig. 15), except that in this “quatrième horizon augustéen” there are also the first productions of SGS. We also find similarities with ITS assemblage of Late Augustan period in the Ampuritan contexts from the forum, namely those from the layer 99-CR-CB-1030 (Aquilué et al. 2010: 36-91).

It must be stressed that contextual data for ITS is extremely rare in southwestern Hispania and that most of this type of fine ware that was identified in the region was originated in disturbed layers. This gives us a unique opportunity to make a series of reflections on the way this imported table ware was being used by this specific urban community.

One of the first observations to be made is the chronology of this deposit that has a very limited time span. According to the association of forms, we have dated this assemblage from the final phase of the Augustan reign. Some of this forms may have had a longer duration than the Augustan period and early Tiberian, but the almost total absence of South Gaulish sigillata which should be expected to be distributed in the region during the Tiberian/Claudian period, allows us to propose this chronology. We have considered one fragment of SGS Drag. 18 as an intrusion from the upper layers since it is dated from a probable Claudian chronology or later. Also, ITS Consp. 37.3 form with applied decoration, which can be dated from Tiberian/Claudian period could be considered in the same situation (fig. 7, no. 57).

With a partial inventory of the ceramics from the site, it is impossible to determine the precise residuality index that was observed. Nonetheless, some information is provided concerning this issue. In fact, in this context SU [501=1011] residuality is expressed by 3 Campanian ware fragments: two bases of Lamb. 5/7and 27A and one rim of a Lamb. 1 plate both in Campanian ware A and B from Cales/Teano (Alves 2010: anexo III and IV). Also in SU [469=994], there were recovered 5 fragments of Campanian B ware from Cales: 2 bases (of forms Lamb. 1 and 3), 2 rims (undetermined, Lamb. 1 and Lamb. 55), as well as 1 undetermined handle (Ibidem). Also in this context: MañáC2 and Dressel 14 amphora from coastal Baetica, Haltern 70 and Dressel 20A from the Guadalquivir, thin-walled ware, Roman grey ware, and a simpulum.

Another aspect to be underlined is the relevant proportion of decorated pieces seen in this specific context when compared to the total amount of ITS in the site. In fact, considering the sample is formed by 36 individuals, there are 6 decorated pieces, not only chalices but also the base of broad beaker R 11.1.1. Considering that some of the decorated fragments may not belong to the pieces identified (fig. 7, no. 64-67), this proportion of decorated pieces, which is in this context of about 16%, might be even higher. Another feature that was observed is the relatively higher proportion of cups when compared to the number of plates.

The interpretation of the function of the compartment was based on the terra sigillata recovered together with the presence of Baetican Haltern 70 and Dressel 20A, as well as Lusitanian Dressel 14 amphorae and was clearly related to the consumption of food, as stated in the reports (Fabião et al. 2006, 2012, 2013).

Considering the future of the research on ceramics from the Early Imperial phase of the site, the homogeneity of this particular contexts, dating from the final phase of Augustus reign will also allow other approaches as to determine the meaning of ITS in the context of the table service and food consumption. In this case, we will be particularly interested in understanding the role of ITS when compared to other different categories of table ware: common ware (local and imported) and thin-walled ware. Italian thin-walled ware is abundant in this context but we weren’t able to develop a systematic study of this category of pottery at this moment.

Apart from this very rare and especially well-preserved context in B3, the remaining assemblage of ITS from Mesas do Castelinho had its provenience mostly in surface layers distributed all over the site in its different sector (A and B), but mostly in sector B 1-4. In fact, half of the ITS (if the number of fragments is considered) is from these surface layers (fig. 2).

In sector B3, some other ITS cups and plates were originated in the abandonment levels of these compartments, as is the case in the US [443] of the previously mentioned compartment XIV; US [444] which is the abandonment level of compartment XVI where were also retrieved Haltern 70 Gualdaquivir amphora, thin-walled ware, and common ware as well as coins and two Campanian ware fragments (Alves 2010) and SU [480] in compartment XIX.

Generally, ITS in these layers (of secondary deposition) is accompanied by South Gaulish and Hispanic sigillata and occasionally also with Peñaflor type sigillata pointing to a chronological framework within the last quarter of the 1st century and the begining of the 2nd century AD.

3.2 South Gaulish sigillata (SGS)

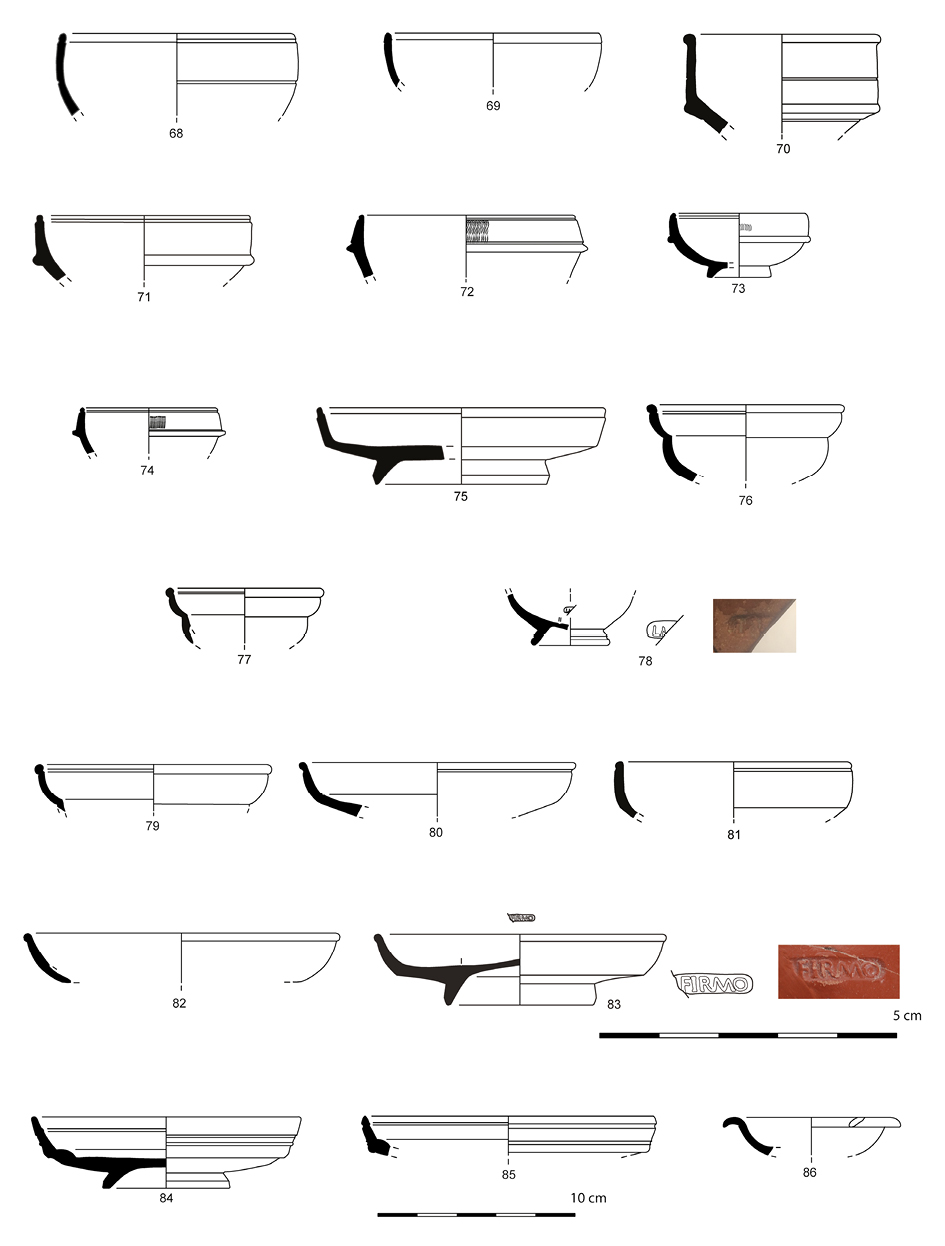

SGS must have started to arrive at the site during Claudian reign or slightly earlier although there is no precise stratigraphic data to support this. La Graufesenque production is predominant and most of the forms have a quite vast chronological scope, such as the cup Drag. 27, and the plates Drag. 18 and 15/17, that is a majority in the inventory (fig. 8-10 and tab. 4 and 6).

Table 4. Distribution of South Gaulish sigillata forms in Mesas do Castelinho (Almodôvar).

|

Frags |

MNV |

||

|

SGS |

Ritt. 8 |

4 |

3 |

|

Ritt. 9 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Drag. 24/25 |

17 |

17 |

|

|

Drag. 27 |

27 |

20 |

|

|

Drag. 18 |

25 |

21 |

|

|

Drag. 17 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Drag. 15/17 |

24 |

13 |

|

|

Drag. 35 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Drag. 35/36 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Drag. 29 |

10 |

5 |

|

|

Drag. 30 |

9 |

7 |

|

|

Drag. 37 |

14 |

7 |

|

|

Undeterm. |

4 |

4 |

|

|

Total |

140 |

102 |

|

|

potter |

legible |

5 |

5 |

|

stamp |

ilegible |

7 |

7 |

The relatively more significant presence of earlier forms such as Drag. 24/25, Ritt. 8, Ritt. 9 and Drag. 17 that are about 18% of all the identified forms (MNV) (seen in comparison to their presence in other sites) (fig. 8, no. 68-75), could be used as an argument in favor of an earlier chronology when compared to the number of vessels belonging to the Flavian services. In fact, Drag. 35/36 and decorated Drag. 37, are just 10% of the whole assemblage. Also, as will be seen in detail infra, from all of the five potters’ stamps, four of them belong to potters who have started their production quite early, beginning in the Tiberian period. On the other hand, in apparent contradiction to what has been mentioned, decorated forms and decorative schemes belong mostly to the Flavian period with Drag. 37 and with the typical motifs of this phase of La Graufesenque (fig. 9).

Figure 8. South Gaulish sigillata from Mesas do Castelinho potters’ stamps.

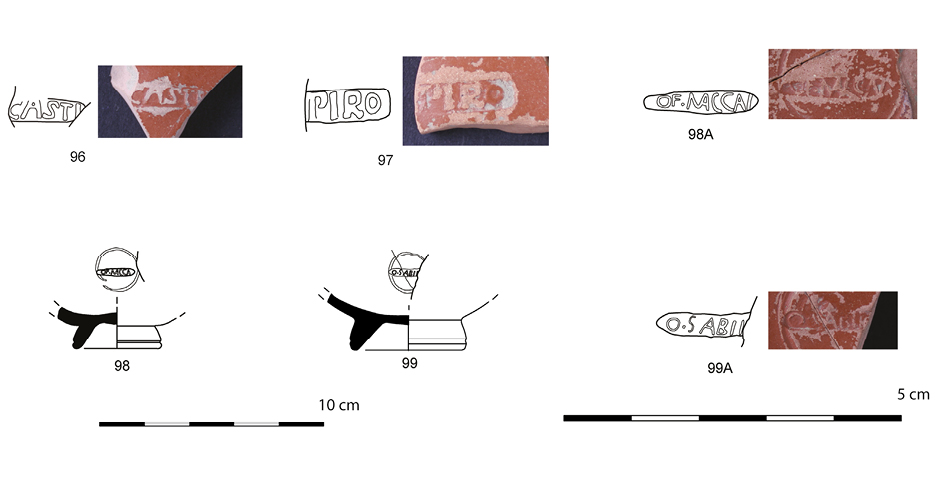

Unfortunately, some potter’s stamps are truncated and are therefore illegible, but in other five examples, we could identify the name of the potter: Castus i, Copiro, Firmo i, Maccarus and Sabinus iii (fig. 10, tab. 6). To evaluate the distribution of these potters we used the Samian Research database available on: http://www.rgzm.de/samian), which was updated with information on Iberian Peninsula sites.

Figure 9. South Gaulish sigillata from Mesas do Castelinho decorated forms.

Castus i (fig. 10, no. 96) is a pre-Flavian potter that laboured from 40 to 70 - the chronology proposed by Polak (2000: 199) was confirmed by Genin/Schenck-David (2007: 190) - and according to NoTS (=Names on Terra Sigillata) its estimated output was of about 30.000 vessels with the dissemination of his production mostly destined to Italy and the Iberian Peninsula (Samian Research: http://www.rgzm.de/samian). In fact, the potter is well known in Spain in Tarraco, Ampurias, Valencia, Baelo (Bourgeois and Mayet 1991: nr. 30, Planche XXX) and in the capital of the province: Mérida. In the Portuguese assemblages, Castus i was identified in several sites, such as Monte Molião (Lagos) (Santos 1971: 352), Torre de Ares (Tavira) (Nolen 1994: fig 20, ss-58), Represas (Beja) (Lopes 1994: nr. 2013) Alcácer do Sal (2 examples) (Faria et al. 1987: nr 28 and 29), Lisbon (Silva 2012: Ol.195, Est. XXVII), Braga (Delgado and Santos 1984: 49-69, nr. 7; Morais 2005: 205, nr. 12) and Monte Mozinho (Carvalho 1993-94: 91-112, nr. 228).

Another stamp is from Copiro (fig. 10, no. 97), though only the letters ...PIRO were preserved. This potter, who is supposed to have produced between 70 and 100 has only 12 stamps in Samian Research database and is, mostly known in France, Germany and England. In the Iberian Peninsula it was referred in Tossal de Manisses (Ribera i Lacomba 1988-89: 199, fig. 3) and Baelo Claudia (Bourgeois and Mayet 1991: nr. 41, Planche XXX) but to our knowledge, no other stamp had already been recovered in today Portuguese territory.

The difficulties in establishing the different potters signing Firmo was cleared in NOTS and two different potters Firmo i and Firmo ii are now proposed. The stamp of Firmo i in a Drag. 18 (fig. 8, no. 83), was identified with the potter Firmo i from La Graufesenque whose production must have started in a quite early period, during the Tiberian reign and lasted until 60-65 (Polak 2000: 227), while according to Genin and Schenck-David, the chronology should be extended from 15 until 70 AD (2007). A Claudian chronology for the Mesas do Castelinho example could be defended, based also on typological details of the Drag. 18. According to the Samian Research database, Firmo i was previously recognized in Tarragona (2 examples) and in Volubilis (Marrocco). Other stamps are known in Baelo (Bourgeois and Mayet 1991: nr. 61, Planche XXXI ) and in Portugal this potter was previously recovered in Represas (Beja) (Lopes 1994: 52, nr. 1930) and in two stamps identified in Braga (Morais 2005: 235, nr. 17 and 18), one of which of Claudian date.

Figure 10. South Gaulish sigillata from Mesas do Castelinho potters’ stamps.

One incomplete stamp where we can read the characters MACCA (with an uncertain or incomplete last letter) belongs to the work of Maccarus (fig. 10, no. 98), that must have started to produce from the Tiberian period onward but it was in the middle of the 1st century that he was most active. According to M. Genin and J.-C.L. Schenck-David, the stamp of this potter was identified with one of the first workshops at La Graufesenque. In this production center, Maccarus is supposed to have worked from 15/10 BC until 60/70 AD (Genin and Schenck-David 2007: 216). Also considered «(…) one of the most prolific potters of the Tiberio-Claudian period at La Graufesenque» (Samian Research database: http://www.rgzm.de/samian), his production was mainly destined to Britannia and Gallia. Despite this trend, stamps of this potter are known in Baelo, Ampurias and Conimbriga (ibd) and its diffusion to Marroco (Banasa) and Algeria (Cherchel) is also attested (Polak 2000: 256-257). In Portugal, several stamps of this potter were recognized in Lisbon (Silva 2012: Ol.12, Est. II, Ol.197, Est. XXVII, Ol.210, Est. XXVIII), Azeitada (Almeirim) (ibd: Sc.Ag.12, Est. LXXV) and Eburobritium (Óbidos) (ibd: Eb.28, Est. LXXX) and in Braga (Morais 2005: nr. 27).

In Mesas do Castelinho there is an example of a cup base with a potter stamp of Sabinus (fig. 10, no. 99), whose production was dated from 50 to 80 AD (see Samian database in http://www.rgzm.de/samian). M. Polak had previously drawn attention to the fact that the stamps with Sabinus had a wide chronology (from 45 until 100 AD), suggesting that it should be the work of two different potters (Polak 2000: 313). In fact, in the stamp from Mesas there is the abbreviation for the officina with the letter O, followed by SABIN, a feature that places this stamp in the earliest group of this series of production: between 50-80 AD. Since the distinction of the different potters Sabinus is relatively recent it becomes more difficult to see its distribution when considering the previously published material. The potter is represented among the Torre de Ares (Tavira) material (Viegas 2011: 318, Est. 19, nr. 124), S. Cucufate (Vidigueira) (Alarcão et al. 1990), Lisbon (Silva 2012: Ol.16 Est. III, Ol.56, Est. X, Ol.144, Est. XIX, Ol.349, Est. XLVIII, Ol.347, Est. XLIX), Briteiros (Guimarães) (Oleiro 1951: 225-229) and Braga (Morais 2005: nr. 54-57) (with 5 examples). In Spain the potter is well represented in Baelo (with 5 examples) (Bourgeois and Mayet 1991: nr. 162-165, Planche. XXXII ) and in Marrocco (Laubenheimer 1979: 99-225). M. Genin and J.-L. Schenck-David (2007) state that the potter was active between 50-100/110 AD.

Considering the whole series of potters’ stamps we could certify that most of them are from the pre-Flavian period, confirming that the first imports of La Graufesenque products must have occurred in Tiberius-Claudian reign. It should be stressed that the site is being supplied by the products from La Graufesenque in a quite early period as was documented by the presence of potter stamps of Firmo and Maccarus. On the other hand, one should stress that when evaluating the pattern of imports of SGS to a specific site, potters stamps should not be seen alone. In fact, there should be a special attention to all aspects of the production, such as plain and decorated forms as well as the potters’ stamps as they often show apparent contradictory trends when seen separately.

Decorated forms are represented by the most common types: Drag 29, 30 and 37 (fig. 9). Despite being incomplete, the decorative schemes and the motifs pictured in some fragments allowed the identification of different phases of La Graufesenque production. Almost in all of the examples of Drag. 29, the decoration didn’t survive or was poorly preserved and the only part that was visible was the row of beads. Best preserved decoration in Drag. 29 (fig. 9, no. 92) shows the upper part of the bowl with a frieze of bifoliated leaves and rosettes followed by the cordon with the row of beads in both sides. In the lower part of the form, another incomplete bifoliated frieze was preserved. Both the moulding and the carinated profile suggest an early Flavian piece.

The cylindrical bowl Drag. 30 is quite frequent and one example (fig. 9, no. 87) shows the lower limit of the ovolo frieze and the panel decoration with plant-derived motifs or circles that include an animal (bear?). Concerning the line of ovolo, the motif is close to type NN, possibly from Marinus, (Dannel et al. 1998: 80 and 82). This decorative scheme is similar to the one used by potter Germanus i whose production is dated from the Neronian phase (Mees 1995: Tafel 68, nr. 1). Other Drag. 30 fragment (fig. 9, no. 88) shows two gladiators and was possibly the work of Aquitanus or Masclus, dating from the third quarter of the 1st century AD (Mees 1995: Tafel 1.3). The same motif was used also by Severus iii, dated from 70-90 and was found in one Drag. 37 of the Atkinson Pompeian hoard (Dzwiza 2004: Tafel XII, nr. 83). In two quite small fragments of another Drag. 30 (fig. 9, no. 90) we identified a possible panel decoration scheme with a vertical foliated line, bordered by undulated lines (not illustrated).

One Drag. 37 (fig. 9, no. 94) displays the line of ovolo with tripartite tongue, close to type SJ that was attributed to Sulpicius (Dannel et al. 1998: 80 and 84), a potter that is dated from 80 to 110 AD (Polak 2000: 339-340). In another example of the same form (fig. 9, no. 95), the line of ovolo seems to be close to SB type, attributed to potter Mommo, dating from 70-90 (Dannel et al. 1998) and the scheme is difficult to determine though it could be formed by medals or undulated scroll. One of the latest examples of this form Drag. 37 (fig. 9, no. 93) shows a decoration that was impossible to reproduce formed by the lower members of a satyre and also of another character (possibly Bacchus), motifs that are usually present in the work of Biragillus, a potter dated from the Domician-Trajan period (Mees 1995: est. 11-14; Tilhard 2004: 436). In a very small fragment of a Drag. 37, only the vertical bifoliated line bordered by undulated lines was preserved and could be part of another zonal decoration of Flavian chronology (MC 6053, not illustrated).

We weren’t able to propose any classification for other fragments as is the case with nr 91 in fig. 9 that presents a scheme also difficult to determine as it is so poorly preserved. There is a possibility that it is a plant-derived motif with circles that include animals (an eagle and a wild boar). The eagle seems to be identical to the one in the Pompeian Atkinson box (see Dzwiza 2004). Also, an identical composition and eagle poinçon is seen in the work of Passienus (Mees 1995: Tafel 158, nr. 1, 89, in this example the lower part of a Drag. 29), a potter who was active in the decades of 60-80. Poor moulding of the piece also denotes a Flavian date.

According to the chronology proposed for the decorated fragments, which was based on the forms identified and in the decorations schemes or the motifs represented, we believe that most of them fall in the Flavian period.

We should also note that in the SGS assemblage, formed by 103 (MNV) only two pieces are marbled (one Drag. 27 and one Drag. 18) which is a relatively small number when compared to sites such as the Roman towns in the Algarve region where the proportion of marbled sigillata is higher (Viegas 2011). In fact, the percentage of marbled sigillata in Faro and Castro Marim is 7,04% and 5,4% (respectively), while in Santarém or Alcacer do Sal is only 2% (Viegas 2013: 271).

3.2.1. Contextual data for South Gaulish sigillata

Concerning the complex stratigraphy in Mesas do Castelinho and the contexts where SGS was retrieved we observed that from the 219 fragments, 123 had their provenience in surface layers with an important part of them being originated in the cleaning the surface of a stratigraphic section visible on the site in the early 1990’s. One should notice that top layers in these sectors are of medieval Islamic chronology and have deeply disturbed the previous occupation levels.

From a stratigraphic point of view, the data on SGS that we could determine, indicates the presence of this fineware in the abandonment levels of the site, in association with Hispanic sigillata, a reality that is particularly visible in sector B (as is the case with US [421], [443] or [458]). In fact, most of the pieces come from abandonment layers of previously remodeled Early imperial buildings.

SGS typological data points to the beginning of the imports from Gaul in the Tiberian or early Claudian period but unfortunately we haven’t identified stratigraphic data of the Claudian period and it seems that some of the Republican/Augustan buildings in sector B3 and B2 might still be in use at this phase. On the other hand, we know that this period corresponds to the moment when the sigillata imports to Mesas do Castelinho clearly start to decrease. In this case, we could only confirm the chronologies previously proposed by the directors of the research project, that point to the abandonment of the urban center at the end of the 1st or the beginning of the 2nd century AD. In fact, some of the decorated SGS fragments point to a chronology of the Domician-Trajan period.

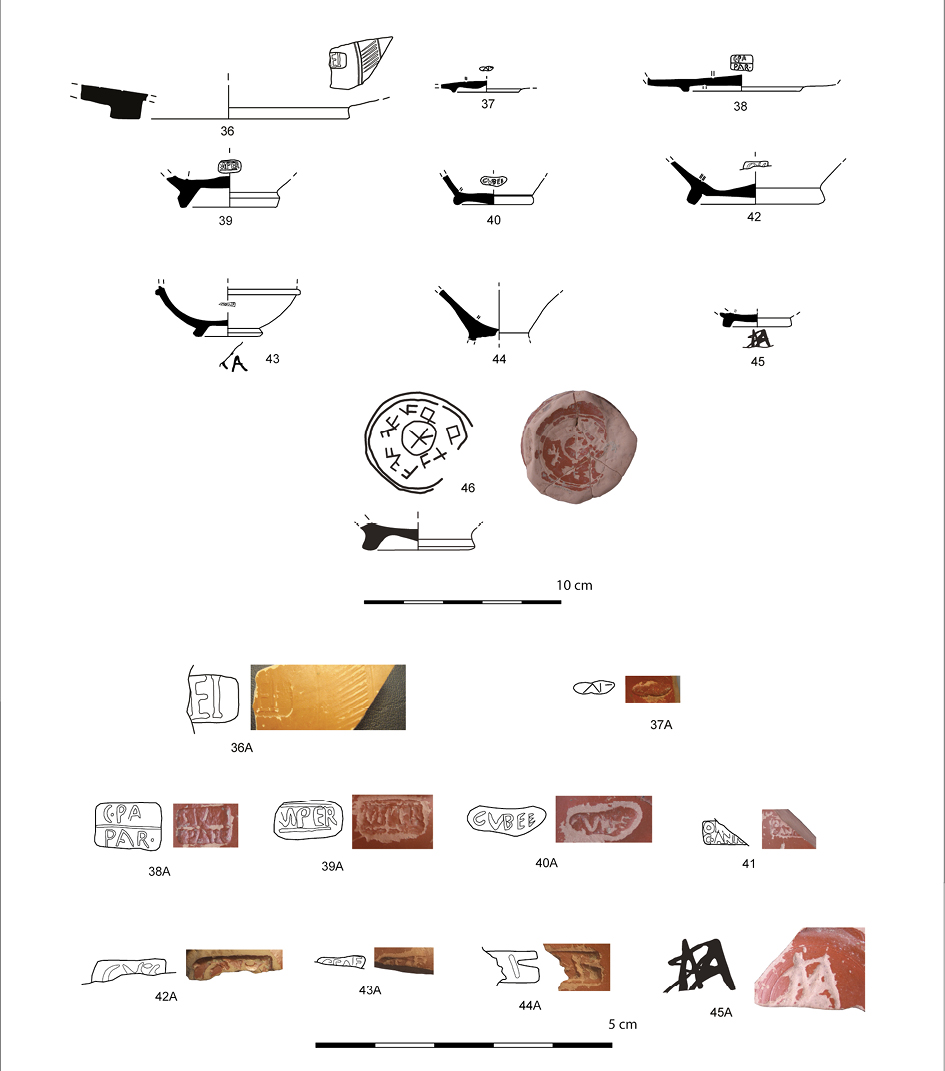

3.3. Hispanic sigillata and Peñaflor type sigillata

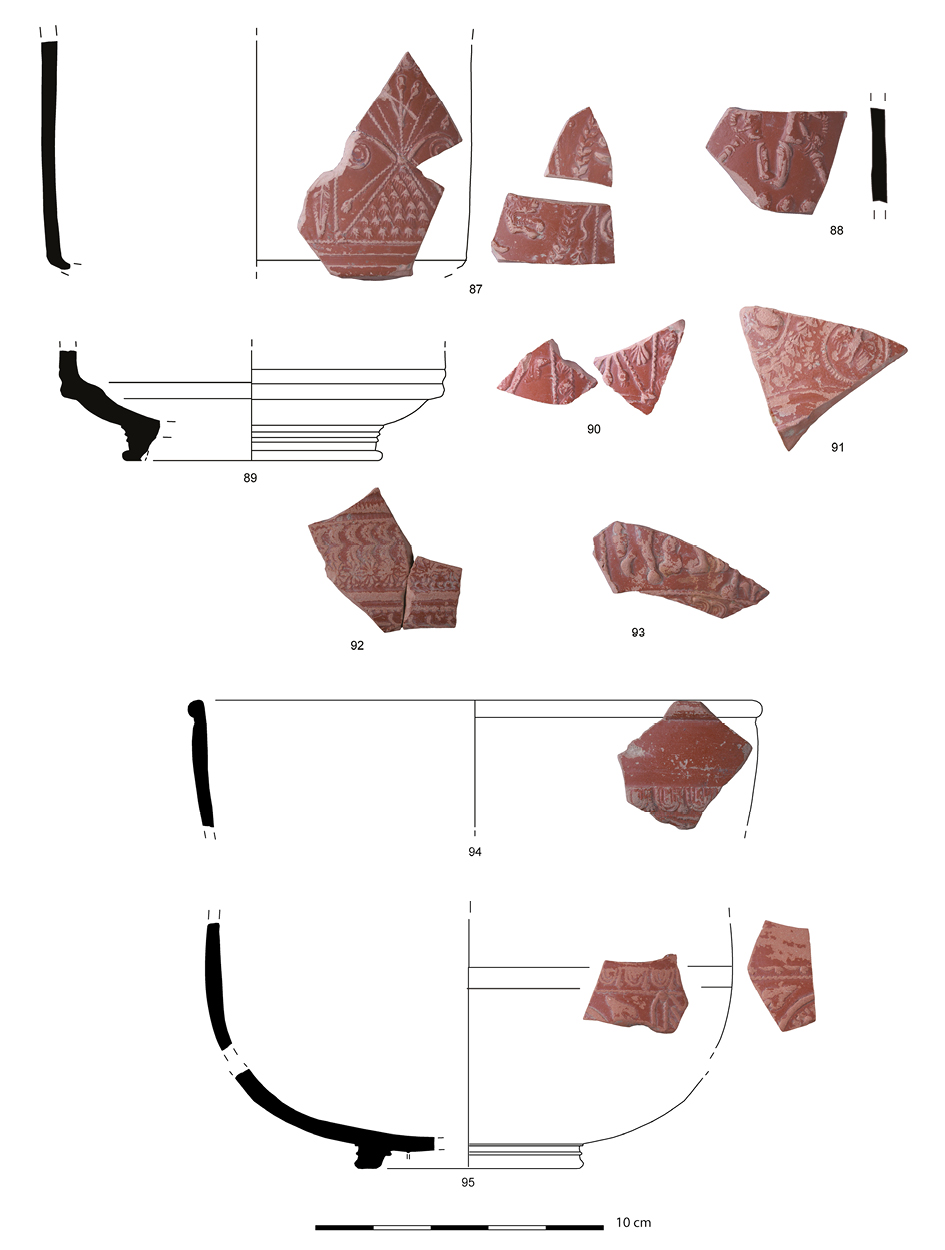

In the last phase of occupation of the site, Hispanic sigillata was also consumed, mainly from the last decade of the 1st century AD onward, when the last imports of SGS were still arriving at the site (fig. 11, tab. 5 and 6). HS is represented by the workshops of Andújar from the Baetican province, as well as the production of Tritium workshops in the Tarraconensis. The Peñaflor type sigillata (“sigillata de imitación tipo Peñaflor”) was also recovered. Discussion on the correct designation of this production is an ongoing issue (Fernández et al. 2014: 56-71), as besides Peñaflor (Celti) (Keay et al. 2001), this type of sigillata has also been produced in Córdova (Vargas and Moreno 2004), Andújar (Ruiz Montes 2013), Cádis (Bustamante and López 2014), and possibly Mérida (Jerez Linde 2004).

Table 5. Hispanic sigillata and Peñaflor type sigillata from Mesas do Castelinho.

|

Frags |

MNV |

||

|

Tricio/ |

Ritt. 8 |

2 |

2 |

|

Andújar |

Drag. 24/25 |

10 |

10 |

|

HS |

Drag. 27 |

33 |

17 |

|

Drag. 18 |

18 |

13 |

|

|

Drag. 15/17 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Drag. 36 |

3 |

2 |

|

|

Drag. 35/36 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Hisp. 17 A |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Drag. 29 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Drag. 29/37 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Undeterm. |

5 |

5 |

|

|

Sub total |

77 |

55 |

|

|

Peñaflor |

Martinez Ia |

1 |

1 |

|

Martinez IIb/c |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Martinez IIIa |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Undeterm. |

6 |

4 |

|

|

Sub total |

9 |

7 |

|

|

Total |

86 |

62 |

Seen together these productions (HS and Peñaflor) are 19,2% of the total assemblage of terra sigillata in the site and show a clear depreciation on the purchasing capacity of the population in Mesas do Castelinho, that will lead finally to the abandonment of the site.

Peñaflor type was identified in Mesas do Castelinho assemblage enlarging the distribution map of this production that was disseminated from different production centers identified in the Guadalquivir valley and the Cadix region, reaching several sites in southern Portugal (see Viegas forthcoming for updated information), the town of Lisbon (Ribeiro 2010: 77; Bugalhão et al. 2013; Santos 2016) though always in quite reduced quantities. Most of the forms were inspired by early Italian sigillata types but also in Pompeian red slip ware, as well as in forms of thin-walled ware. Their chronology extends from the Augustan until the Flavian period. Due to the poor preservation of most of the fragments for most of them we weren’t able to identify the form. Diagnosed types are the plates Martínez II and IIIa and the cup Martínez Ia which, as was mentioned above, was recovered in the specific Late Augustan context in sector B3. This fact should be highlighted since most of the Peñaflor type sigillata recovered in other sites wasn’t part of a homogenous context as was the case in Mesas do Castelinho.

A reflection should be made concerning the ITS forms that have inspired Peñaflor type sigillata. In southern Portugal these types are mostly represented by the cups Martínez types I (a and b variant) and the plates Martínez II (a and b) which are well represented in the urban sites in Southern Portugal; though the most common form is, by far, the one based in the Pompeian red slip ware dish (Martínez III type, and its variants) (Viegas 2011). It should be stressed that this form is used in the context of the tableware and the consumption of food since none of the pieces has any sign of having been exposed to fire for the preparation of food, as happens with the Italian prototypes.

Although is not easy to find the key to understand what might have motivated the local potters, (mostly located in the Guadalquivir valley), to produce such forms inspired in the Italian type sigillata and those that follow the Pompeian red slip ware, it’s true that a previous pre-Roman and Late Republican tradition of the Kouass ware seems to have provided the know–how to allow the manufacture of fine table red slip wares as M. Bustamante and E. López have recently defended (2014). In this context, these imitations could be interpreted as a clear testimony of an early adaptation of local potters to Roman Italian forms used in tableware, in a phase when the Italian sigillata imports were not so abundant yet. In fact, one should see these types as a response to the early impact of the circulation of Italian sigillata in southern Lusitanian sites. These Penãflor type plates and cups seem to copy forms of the service I of Haltern, that are relatively rare and that announce the following arrival of the most frequent forms of the service II of Haltern that are relatively common in most of the southern sites.

Figure 11. Hispanic sigillata, Peñaflor type sigillata and Late Phocaean red slip ware from Mesas do Castelinho

(plain forms 1:3, potters’ stamp 1:1).

Most of the repertoire of forms of HS from Tritium and Andújar is similar to what is usually recovered in Lusitanian sites, with a majority of Drag. 27, followed by type 18, 24/25, 15/17 and 35/36, that are direct descendants of SGS types (Fig. 11). Typical Hispanic forms are reduced to one fragment of form 17 that could be integrated in the B variant, dated from the Vespasian period (fig. 11, no. 106) (Bustamante 2013: 79-82). Note that in some previous publications the same form was integrated in type Ludowici Tb. Most of the forms are represented by small fragments, but whenever the type is better preserved and the variant of the form could be established it belonged to the variants that could be integrated in the Flavian period or the beginning of the 2nd century, as is the case for the form 8 or 27 (fig. 11, no. 102, 107 and 108) (ibd: 72-77 and 95-98). Decorated forms are rare and badly preserved (not illustrated) and there are no fragments with the typical motifs of concentric circles usually attributed to the 2nd century AD. There are two potter stamps in HS, but one is unfortunately unreadable. In the other, we could read ... F FVSCVS with the C rectograde that was attributed to the potter Fuscus i from Bezares/Tricio workshops in Tarraconensis (Mayet 1984: nr. 227). We were not able to determine the full extent of this potters’ diffusion apparently unknown in the Portuguese collections but another potter stamp was identified in Carteia (Beltrán 1990: 114).

Table 6. Potters’ stamps and grafitti on Italian, South Gaulish and Hispanic sigillata. Oxé, Comfort, Kenrick

(= OCK); Names On Terra Sigillata (= NOTS) in Samian database (https://www1.rgzm.de/samian).

|

fig. and no. |

Potter’s name |

reading |

Samian Research database OCK /NOTS |

Origin |

Date |

Form/ position |

|

fig. 7, no. 58 |

C. ANNIVS, slave GEMELLVS |

GEME/ C·ANI |

OCK 147.2. |

Arezzo |

15 BC + |

Internal stamp on a base of cup Consp. B 4.2 |

|

fig. 5, no. 36 |

ATEIVS (2) radial |

…EI |

OCK 267.26 |

Arezzo |

15 – 5 BC |

Internal stamp on a base of plate Consp. B 1.3 |

|

fig. 5, no. 37 |

ATEIVS (3) (?) in planta pedis |

AT ? |

OCK 268.140 |

Pisa |

5 BC – |

Internal stamp in a Base of possible Consp. 28. |

|

fig. 5, no. 38 |

C. PAC(IDEIVS) PAR( ) |

C·PA ?/·PAR |

OCK 1367.2. |

Central Italy ? |

15 BC - |

Internal stamp of a cup Consp. B 2.10 |

|

fig. 7, no. 62 |

M. PERENNIVS (4) |

M·PER |

OCK1390.4 |

Arezzo |

15 BC - |

Intradecorative stamp on a chalice Consp. R 4.2.1 |

|

fig. 5, no. 39 |

M. PERENNIVS (4) |

MPER |

OCK1391.44 |

Arezzo |

20 BC - |

Internal stamp on a base of cup Consp. B 3.9. |

|

fig. 5, no. 40 |

Potter stamp of C. VIBIENVS (2) in planta pedis |

CVBE |

OCK 2373.66 |

Arezzo |

1 – 50 AD |

Internal stamp on a base of cup Consp. B 4.6 |

|

fig. 5, no. 41 |

Potter stamp C. ANNIVS, slave Orbius ? |

OR.../ C.ANN... |

— |

ITS |

— |

Internal stamp on undetermined form |

|

fig. 5, no. 42 |

Incomplete potter stamp |

CV… |

— |

ITS |

— |

Internal stamp on a base of a cup Consp. B 4.7. |

|

fig. 5, no. 43 |

Incomplete potter stamp in planta pedis |

CFA ? |

— |

ITS |

— |

Internal stamp on a base of Consp. 33. grafito CA outside the base of a cup. |

|

fig. 5, no. 44 |

Incomplete potter stamp |

…I |

— |

ITS |

— |

Internal stamp on thebase of a cup. |

|

fig. 5, no. 45 |

No stamp |

— |

— |

ITS |

— |

External grafito with NA scratched on the base of a cup |

|

fig. 5, no. 46 |

No stamp |

— |

— |

ITS |

— |

Internal grafito on the base of a cup |

|

fig. 10, no. 96 |

Castus i |

CAST… |

NOTS Nr 42260, 17 |

La Graufesenque |

40 - 70 AD |

Internal stamp undetermined form |

|

Fig. 10, no. 97 |

Copiro |

...PIRO |

NOTS Nr 50450, 1a |

La Graufesenque |

70 – |

Internal stamp undetermined form |

|

Fig. 8, no. 83 |

Firmo i |

FIRMO |

NOTS Nr 63324 9- b |

La Graufesenque |

AD 30 – 60? |

Internal stamp on Drag. 18. |

|

fig. 10, no. 98 |

Maccarus i |

OF·MACCAI |

NOTS Nr 83744 13- j |

La Graufesenque |

30-65 AD |

Internal stamp on a possible Drag. 27 |

|

fig. 10, no. 99 |

Sabinus iii |

O·SABIN ... |

19- b |

La Graufesenque |

50 – 80 AD |

Internal stamp on a possible Drag. 27 |

|

fig. 8, no. 78 |

Incomplete /truncated potter stamp |

LA |

— |

South of Gaul |

— |

Internal stamp on a possible Drag 27 |

|

fig. 11, no. 109 |

Fuscus |

FFVSCVS |

Mayet, 1984: 137, nr 217 |

Bezares Tricio |

— |

Undetermined form. Stamp with C retrograde |

|

— |

Unreadable potter stamp |

— |

— |

HS |

— |

Undetermined form |

As said before, the presence of this quite small percentage of HS is a testimony of the decline of the site that could be related to the degradation on the purchasing capacity of the population and consequence of the progressive abandonment of Mesas do Castelinho.

3.3.1.Contextual data for Hispanic sigillata and Peñaflor type sigillata

The main observations made for SGS could be repeated here also concerning the archaeological context for HS. In fact, most of the fragments recovered are provenient from the surface layers of the site, in sector B1-3 but also in B4. These are disturbed layers where occasionally Islamic presence is noted.

Apart from surface layers, HS is represented, in sector B3, in the abandonment layers that cover the last construction phases dated from Early Roman period (e.g. SU [421] and [444] are good examples), usually associated with SGS imports.

Considering that we should expect the beginning of HS imports to have occured from the Vespasian period onward and knowing that the definitive abandonment of the site must have taken place in the end on the 1st century AD, there is a quite limited time span for the consumption and discard of this category of sigillata in Mesas do Castelinho. In a certain way this also helps to explain its relatively low percentage being only 19,2%. As seen above, this contextual data cannot provide new perspectives concerning the chronology of the early phases of the diffusion of Hispanic sigillata, since the stratigraphy of this period is marked by the abandonment of the site together with important disturbance due to the Islamic settlement.

4. Final remarks

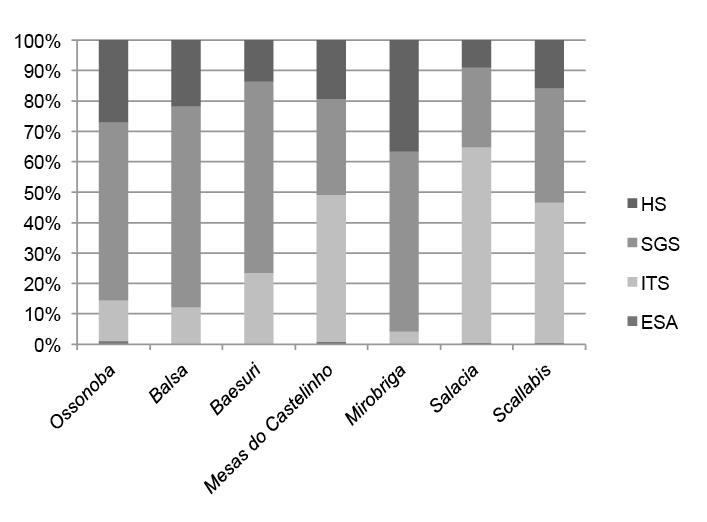

The confrontation of sigillata pattern of import of Mesas do Castelinho should be done firstly with the coastal sites of the Algarve, location from which the site must have been supplied. A comparison with Faro (Ossonoba) is, however, rather limited as the ITS assemblage is formed by a relatively small set of 27 individuals (yet diversified) (Viegas 2011: 130-138). Torre de Ares – Tavira (Balsa) and Castro Marim (Baesuri) offer a good standard of comparison when we intend to evaluate the distribution of this ceramic category, especially the latter, given the location of this urban center in the lower course of the Guadiana river (ibd: 292-297). In fact, if we consider that this river would have been an important penetration route to the interior of Alentejo, Castro Marim could provide important clues to the understanding of the distribution of such material. On the other hand, the observation and analysis is limited by the difficulty to compare the patterns of import in Mesas with those from Mértola, the Roman city that might have played the role of redistribution center for the region where Mesas do Castelinho is located. Unfortunately, the High Empire Roman occupation of Mértola (Myrtilis) is not so well known and it is not possible to assess the consumption patterns present in this site. As already mentioned it should be emphasized the fact that the monetary findings in Mesas show the close relationship between Mesas do Castelinho and Myrtilis.

Exploring another line of research, we can also make a comparison of the profile of import of Mesas with the one in other urban centers from more distant areas. In this context, we selected sites like Miróbriga, (Santiago do Cacém), Salacia (Alcácer do Sal), in the valley of the Sado and Scallabis (Santarém), on the Tagus valley, as urban centers integrated in this broader region of south-central Portuguese territory.

Based on the assemblages of ITS known in the Portuguese territory we were able to delineate some distribution trends about the circulation of these products in one hand, and to confirm other lines of interpretation that were previously outlined.

In fact, the first imports of ITS, testified by the forms Consp. 1, Consp. 12 e 14 and the radial stamps are present, though in small quantities, in coastal urban centers, such as Castro Marim (ancient Baesuris) in the mouth of the Guadiana river (Viegas 2011). Further north, the Roman towns in the Sado and Tejo valley imported more significant assemblages of earlier ITS. Examples of this phase are also the urban contexts in Santarém (ancient Scallabis) in the Tejo estuary (Viegas 2003) and Alcácer do Sal (ancient Salacia), where the percentage of pieces of the service I of Haltern is significantly higher (Viegas 2014: 755-764, with Bibliography of earlier studies by other authors).

In the upper Alentejo region, there is a series of sites that can also be integrated in this early phase and that, in some cases have had a military function related to the logistic support and to the consolidation of the province of Lusitania. Sites like Castelo da Lousa (Carvalho and Morais 2010: 139-151) and Caladinho (Mataloto et al. 2014: 17-43; 2015) share this features and were mentioned above. One should note that the military nature of these sites, including Castelo da Lousa, was widely discussed, but we shall not develop this subject here. Regardless of this fact, it appears that the presence of the early forms of ITS in today Portuguese territory had a mainly urban and civil character. It is in this context that we must also integrate the importation of ITS to Mesas do Castelinho. However, it is unwise to dismiss and devalue its association to the possible dislocation of military contingents in the inland upper Alentejo region, that those sites are an example.

In a second phase of the imports, which corresponds to the end of the Augustus reign and that covers also the Tiberian period, we have seen, that it coincides with the moment of the major production in the various production centers of the Italian peninsula with large-scale Arretine workshops manufacture. Simultaneously, in the context of the Iberian Peninsula and more specifically the Portuguese territory, this phase is contemporary to the period of the creation and consolidation of the province of Lusitania and the establishment of the urban and road network and is the period of greatest importation and consumption of the Italian production.

In Mesas do Castelinho it was possible to recover a rare consumption context related to the remodeling of a particular area of the site (sector B3), with a well preserved and homogenous context dated from the late Augustan period. The association of Italian sigillata imports to Baetican amphora commerce (Haltern 70, Dressel 20, Dressel 7/11 and Beltrán 2B) could also be established both for Mesas do Castelinho and the coastal towns in the Algarve, such as Baesuri, (Castro Marim), Ossonoba (Faro) and Balsa (Torre de Ares) (Viegas 2011).

In this regional context, the Baetican town of Cadix must have had a crucial role in the commercialization of the Italian products, the town acting as a logistics platform and main redistribution center towards the southwestern Lusitania. From there, ITS imports would supply major Lusitanian urban centers such as Baesuri, Myrtilis and Ossonoba. Roman Hispalis (today Seville) must have been also relevant, considering the importance of the products supplied by the Guadalquivir region, following a long-term tradition of pottery production (table and common ware) together with foodstuff (olive oil and wine products) transported in amphorae.

Commercial dynamics of today Huelva region (Onuba Aestuarina) should also be valorized in the context of redistribution when addressing the circulation of products in today Algarve in early imperial period (Campos, Vidal and Bermejo 2012).

The first SGS imports to the site must have begun in a moment when local population was still acquiring ITS. From the Claudian period onward we believe that the SGS must have imposed definitely in the markets. This period corresponds to the gradual decrease of the activity on the site. Despite this fact, the amount of SGS is relevant and allowed the identification of trends that seem discordant. Plain forms and potter stamps are mostly related to the earlier pre-Flavian phases of La Graufesenque and, in apparent contradiction, decorated fragments report a strong presence for designs and decorative schemes of the later Flavian phases.

HS has a minor proportion and were the last imported tableware to the site that was abandoned in the end of the 1st or the beginning of the 2nd century AD. Apart from a few examples, most of the Hispanic sigillata that has arrived to Mesas do Castelinho, (either from Tritium or the Guadalquivir valley), could be contemporary to the later Flavian/Vespasian SGS. There is no further evidence of the occupation of the 2nd century onward except for a fragment of ARS A form Hayes 9 A that was recovered in surface layers and is usually dated from the second half of that century. The sole example of Late Phocaean Red Slip ware form Hayes 3D is the proof that despite being abandoned for quite a long period of time, the site may have occasionally been attended in a moment around the third quarter of the 5th century. The final Islamic occupation of the site took place from the 9-10th until the 12th century.

Figure 12. Percentual distribution of Early Empire terra sigillata from Ossonoba, Balsa, Baesuri, (Viegas 2011); Mesas do Castelinho, Mirobriga (Quaresma 2012), Salacia (Viegas 2014) and Scallabis (Viegas 2003)(MNV).