The Nilotic in Hispania: the pictorial ensemble of Calle Suárez Somonte in Augusta Emerita

Lo nilótico en Hispania: el conjunto pictórico de la calle Suárez Somonte de Augusta Emerita

Eleonora Voltan

Departamento de Prehistoria y Arqueología,

Facultad de Geografía e Historia

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia

Paseo Senda del Rey 7, 28040, Madrid

evoltan@geo.uned.es  0000-0003-4750-3062

0000-0003-4750-3062

Santiago Feijoo Martínez

Consorcio de la Ciudad Monumental de Mérida

C/ Santa Julia 5, 06800 Mérida, Badajoz

sfeijoo@consorciomerida.org  0000-0003-0046-5820

0000-0003-0046-5820

Fecha recepción: 23-06-2025 | Fecha aceptación: 21-08-2025

Abstract The paper focus on the study of a painted panel found during the 2021 archaeological excavations of a residential building located at number 28 Suárez Somonte street in Mérida, carried out by the Consorcio de la Ciudad Monumental. The wall paintings are linked to a late imperial public bath complex, currently dated to the 1st century CE. Although the decorative scheme has only been partially preserved and documented, the surviving iconographic elements clearly indicate the representation of a Nilotic landscape. The detailed analysis of this painting provides insight into the spread of this figurative theme in Hispania and its relationship with Italian models.

Keywords Egypt, Nile, Iconography, Landscape, Roman painting, Baths.

Resumen El presente artículo aborda el estudio del panel pictórico que se documentó en la excavación arqueológica de una casa de la calle Suárez Somonte n.o 28 de Mérida realizada en el año 2021 por el Consorcio de la Ciudad Monumental. Las pinturas pertenecen a unas termas públicas alto imperiales, fechadas en el siglo I d.C. En este conjunto, pese al hecho de que se ha podido documentar solo parcialmente, se observa la representación de un paisaje identificable como nilótico por los elementos iconográficos aún conservados. A través del análisis pormenorizado de esta pintura resulta posible reflexionar sobre la difusión de este tema figurativo en Hispania y su relación con los modelos itálicos.

Palabras clave Egipto, Nilo, iconografía, paisaje, pintura romana, termas.

Voltan, E. y Feijoo Martínez, S. (2025): “The Nilotic in Hispania: the pictorial ensemble of Calle Suárez Somonte in Augusta Emerita”, Spal, 34.2, pp. 176-193. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/spal.2025.i34.18

Index

3. The pictorial ensemble from calle Suárez Somonte

3.1. The Nilotic motif in the Roman painting repertoire

3.2. The iconographic and stylistic analysis of the Nilotic painting from Augusta Emerita

Captions List

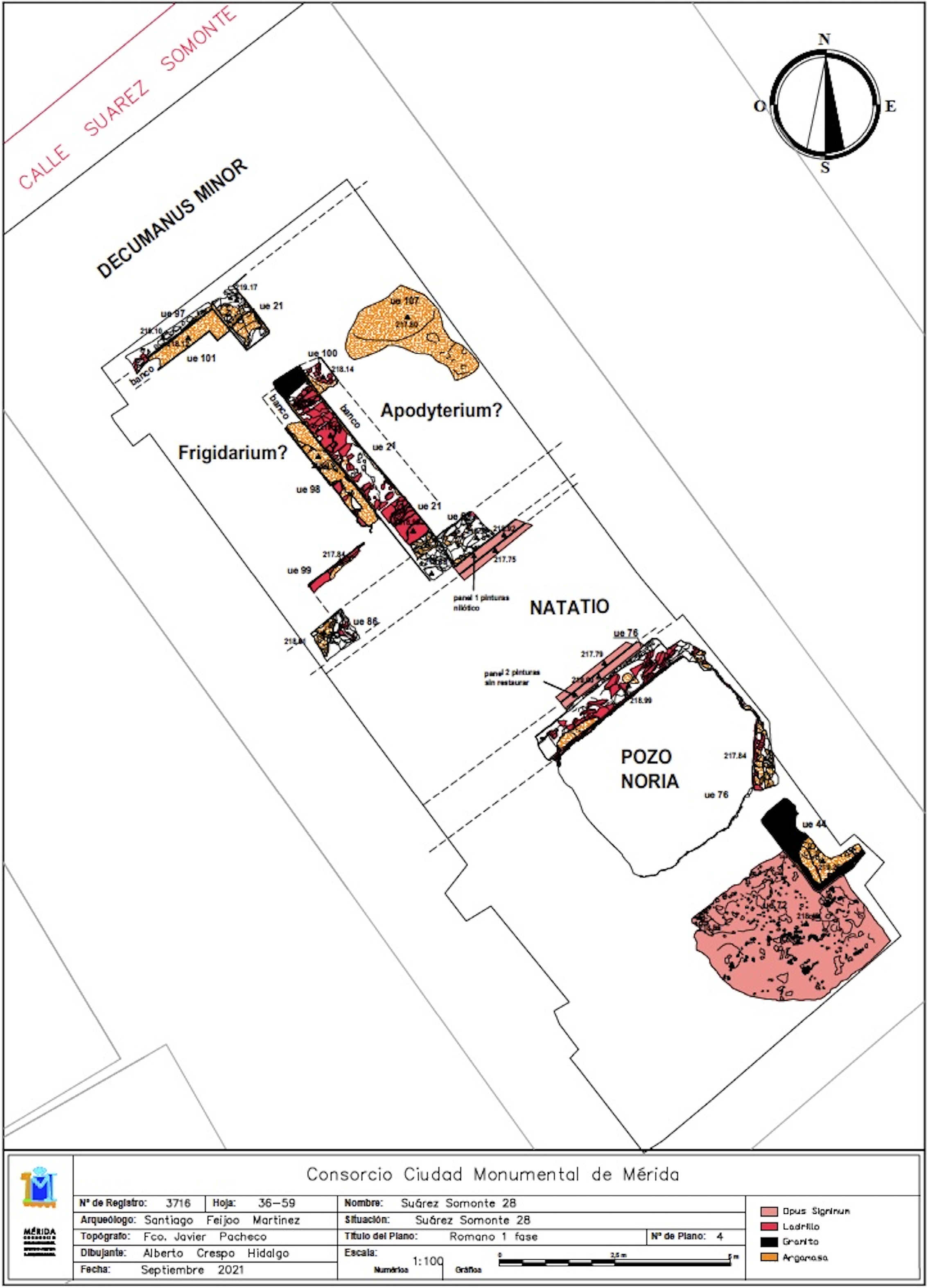

Figure 2. Plan of the first phase of the thermal baths building. Elaboration: S. Feijoo Martínez.

Figure 4. View of the Nilotic painting in situ . Photo: S. Feijoo Martínez.

Figure 5. Nilotic painting in situ . Photo: S. Feijoo Martínez.

Figure 7. Detail from the Nilotic mosaic of Palestrina. From Bernard, 2003, p. 78.

Figure 8. Nilotic painting from Herculaneum (MANN, inv. 8651). From Voltan, 2023, p. 39, fig. 3.10.

Figure 9. Detail of the Nilotic painting in situ . Photo: S. Feijoo Martínez.

1. Introduction ^

Mérida, or Colonia Augusta Emerita as mentioned by Pliny the Elder (HN 4.117), is one of the most important Roman cities on the Iberian Peninsula. It stands out not only for its archaeological heritage, but also for its ongoing urban and socio-political evolution spanning over five centuries (Nogales and Álvarez Martínez, 2014, p. 209). Founded between 23 BCE (Hidalgo and Feijoo, 2023) and 25 BCE by order of Emperor Augustus (Cas. Dio. 53.26.1; Mateos, 2001; Arce Martínez, 2004; Feijoo and Alba, 2008; Álvarez Martínez and Nogales, 2010), the city was established under the direction of the legatus Augusti pro praetore Publius Carisius (Blázquez Cerrato, 2010). Its location was carefully selected for both strategic and economic purposes: it rose at the confluence of the Guadiana and Albarregas rivers, on fertile Quaternary terraces that had been intermittently inhabited since prehistoric times (Enríquez Navascués, 2003; Jiménez Ávila and Barrientos, 2019). The foundation of Augusta Emerita was primarily intended to secure Roman control over newly conquered territories in western Hispania, following the protracted and violent campaigns against the Lusitanians, Gallaeci, and Cantabrians (Heras, 2019, p. 271). In this context, the city functioned as a keystone in the consolidation of Roman power and the pacification of the region. Its establishment was also driven by economic motivations, notably the exploitation of the area’s rich mineral resources and agricultural potential. Situated along the crucial Vía de la Plata (“Silver Route”), a Roman road that connected the northern and southern regions of the peninsula, the city enjoyed a privileged position within the imperial transport and communication network (Mateos, 2001). This strategic placement facilitated not only the movement of troops and goods but also the efficient transport of construction materials such as granite, quartzite, and clay, resources that would later contribute to the city’s monumental architecture (Acero, 2011).

Initially conceived as a settlement for veterans of the V Alaudae and X Gemina legions, the city was granted the status of colonia civium romanorum and enjoyed ius Italicum, a legal privilege that exempted its citizens from certain taxes and granted them rights equivalent to those of citizens in Italy (Arce Martínez, 2004, p. 8; Palma, 2019, p. 319). Although the city did not possess a strongly militarized character in its early years, its role evolved rapidly. With the administrative reforms initiated by Augustus, Augusta Emerita was designated as the capital of the newly created province of Lusitania, further cementing its symbolic and political significance (Acero, 2013). Despite the relative scarcity of surviving material evidence from its earliest phase, archaeological investigations have uncovered remnants of Augustan-era structures, including portions of urban infrastructure, ceramic assemblages, and wall paintings dating from the late first century BCE (Alba, 2004; Álvarez Martínez, 2008; Álvarez Martínez and Nogales, 2011; Corrales Álvarez, 2016; Castillo Alcántara, 2021). These findings, though limited, support the view that the city was conceived from the outset as a carefully planned urban project, embodying both the logistical necessities and the ideological aspirations of the Augustan regime. Mérida thus emerged as a city that blended military rationale with ideological projection (Saquete, 2011). It served not only as a means of veteran resettlement but also as an emblem of Roman civilization and imperial order in the westernmost territories of the Empire. The colony’s foundation represents a clear instance of Augustus’s broader strategy: using urbanism, colonization, and monumental architecture to project Roman authority and culture across the provinces (Álvarez Martínez, 2004; Álvarez Martínez and Nogales, 2011). In this sense, Augusta Emerita represents a carefully orchestrated expression of Roman imperial identity, power, and permanence on the Iberian frontier.

2. Archaeological context ^

The painting analysed in this paper was discovered during the 2021 archaeological excavation of a house at 28 Suárez Somonte street (calle) in Mérida, conducted by the Consorcio de la Ciudad Monumental. The paintings are part of a public bath complex dating back to the early 1st century CE, according to the structure and findings reported by the Consorcio’s archaeologists. However, the excavation covered only a 100 m² area, significantly smaller than the original complex, which likely exceeded 1000 m² and occupied a large portion of the Roman insula where it was situated. This limited scope complicates interpretation of the functions of the uncovered spaces, particularly since the structure was demolished between the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE to construct a new bath complex. This later phase disrupted and concealed much of the earlier layout, hindering efforts to reconstruct the original configuration. The site lies adjacent to the forum of the Roman colony, giving it particular importance due to its location within the civic centre, surrounded by the city’s most significant public buildings (Feijoo and Alba, 2008) (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Map of Augusta Emerita indicating the thermal baths at Suárez Somonte street 28. Elaboration: S. Feijoo Martínez. ^

The initial entrance to the baths likely faced a decumanus minor to the north, where archaeological evidence of a pedestrian pavement and a staircase belonging to the second phase has been found, indicating that the baths served a public rather than private function. Although the first bath complex is only partially preserved (cf. fig. 2), several rooms are discernible. Behind the façade wall are two interconnected spaces, both featuring benches. These may correspond to the apodyterium and frigidarium. To the south lies a pool measuring 2.80 meters in width and 1.20 meters in depth, entirely lined with opus signinum. The full length of the pool is unknown, as it extends beyond the excavated area. It lacks evidence of a hypocaust, making it unlikely to have functioned as a tepidarium. It more closely resembles a natatio. While it seems to have been open-air, this cannot be definitively confirmed. Next to the southern edge of the possible natatio, the remains of a large well, probably a noria (water wheel), used to draw water for the baths, can be identified. Due to the city’s high-water table, it was more practical and economical to draw water from this source rather than from aqueducts, which were reserved for more prestigious uses such as public fountains (Feijoo, 2005; 2006; Álvarez Martínez, 2011).

Figure 2. Plan of the first phase of the thermal baths building. Elaboration: S. Feijoo Martínez. ^

The original complex was demolished down to the first floor to construct a new bath building between the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, with a completely different layout. The natatio - where the Nilotic panel is placed - and one of the changing rooms were full of debris from the raw brick walls, used to raise the floor level by about two metres. A bath was probably constructed over the former apodyterium, of which only the drainage channel remains. The adjacent room was converted into a cistern and left underground. From this second phase, the only space that can be confidently identified as a possible frigidarium is a small apsidal pool, once covered in large marble slabs (now removed), from which a drainage channel runs eastward. The pool is flanked by thick walls that likely featured niches and supported a barrel vault perpendicular to the stepped entrance. Its architectural features, including a central opening with two columns, are comparable to the Baths of Caracalla in Rome (Piranomonte, 1998). The waterwheel remained in use during this period.

Moreover, the analysis of the walls of the thought-to-be frigidarium revealed three layers of plaster. The finish layer was topped with white plaster, and underneath there was a pink plaster layer that was put on using a tapping technique to help it stick better. Although not preserved, it can be assumed that this pink layer derives from the inclusion of crushed ceramics suitable for waterproofing the mortar. The last preparatory layer, approximately 3 cm thick, adheres firmly to the wall mortar and has a finer and whiter finish on the surface. Additionally, although no definitive archaeological data are available, the use of a traditional and common zigzag fixing system could be assumed. The process described was repeated over time, with the introduction of a much thicker final preparatory layer, consisting of successive 5 mm preparatory layers applied while still wet and finished with a smoother, whiter layer of lime that was polished. However, after cleaning by the restorers, only faint bluish shadows are visible. It is unclear whether these are pigment residues or discolouration caused by the burial conditions, or whether they were part of a painted decoration intended to imitate marble. Where best preserved, on wall 97 and at the beginning of wall 21 to the north, the surface appears as a uniform cream-coloured panel.

To the south lies what may have been a courtyard or secondary pool, draining into a large sewer that cuts through a wall over two meters thick. This wall leads to a semi-subterranean space whose function remains unclear. However, the presence of ash on the floor and the wall’s considerable thickness suggest it may have been the hypocaust of a caldarium, designed to support the heavy vaulting typical of such warm and humid rooms. What stands out is the continuous maintenance and decorative enhancement of the first thermal complex throughout its use, culminating in its complete demolition to make way for a new, more robust and richly adorned bath structure, apparently finished in part with marble. All evidence indicates that this was a public bath - both the older and the later building, generously funded and carefully maintained over a long period, likely supported by the colonial administration, or possibly through acts of imperial evergetism. It was probably among the most significant bath complexes documented in Augusta Emerita (Palma and Bejarano, 2023).

3. The pictorial ensemble from calle Suárez Somonte ^

Within the initial building complex described above, a small perimeter wall was also uncovered, measuring 65 cm in height and originally coated with signinum, which surrounded the pool (fig. 2). This wall was later embellished with Nilotic-themed wall paintings, which will be analysed in detail below. However, due to restoration work, it was not possible to study the mortar on this panel. In any case, it can be assumed that it dates back to the same period as the frigidarium and therefore may have a mortar similar to that analysed in the previous paragraph. It may also have been characterised by the presence of a pink preparation layer, derived from the presence of crushed ceramics, which is probably also present in the frigidarium. Moreover, the analyses carried out did not allow for a more in-depth study of the technical characteristics of this panel, due to the absence of preparatory traces and information on the fixing system.

It seems reasonable to assume that these paintings were originally exposed to the open air, positioned at the height of the bathers’ heads, such that the water level would have remained below the signinum-lined edge and would not have reached the small cornice above which the frescoes were painted (fig. 3). The painted panel is preserved to a total length of 1.44 meters and a height of 0.65 meters (figs. 4 and 5). The decoration is organized into distinct horizontal zones. The lower section consists of a red band, which exhibits numerous signs of chips and scratches in the preserved area that do not appear to result from burial, as they are restricted to this specific zone. It is more plausible that the damage was caused by regular use, possibly by bathers leaning against the ledge or placing objects on it, resulting in wear. Similar signs of intensive use are visible on the walls of other rooms, where they prompted multiple plaster repairs. These are also evident in the painted pool area and consist of later additions to the original surface. Above the red band, a narrow white strip marks the transition to the central register, where the figurative scene is located (see 3.2). Before analysing it in detail, a brief overview of the characteristics of Nile scenes in Roman wall painting will be provided.

Figure 3. Hypothetical reconstruction of the pool and the painting’s position. Elaboration: S. Feijoo Martínez. ^

Figure 4. View of the Nilotic painting in situ. Photo: S. Feijoo Martínez. ^

Figure 5. Nilotic painting in situ. Photo: S. Feijoo Martínez. ^

3.1. The Nilotic motif in the Roman painting repertoire ^

The fascination with the land of the Nile found compelling expression in Roman visual culture through the widespread depiction of Nilotic landscapes, a motif that first emerged during the Late Republican period and reached the height of its popularity in the Imperial era. This aesthetic and iconographic trend, often described as a cultural “fashion,” was largely fuelled by the intensification of political, economic, and artistic exchanges between Egypt and the Roman world following the annexation of Egypt as a Roman province after the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE (De Vos, 1980, pp. 75-89; Bragantini, 2006; Capriotti Vittozzi, 2006, pp. 37-49; Swetnam-Burland, 2015, pp. 75-89). From a chronological perspective, the Nilotic theme persisted in Roman artistic production from the 2nd century BCE to at least the 6th century CE, spanning a vast geographical area that included not only Italy but also the provinces of Hispania, Gaul, Libya, Egypt, Cyprus, Greece, and the region of Judea (Voltan, 2023). This iconographic motif appeared on a variety of media, in addition to paintings, such as mosaics, stucco reliefs and even sculptures, proving the adaptability and timeless appeal of the subject throughout the centuries and across different contexts (Versluys, 2002). A number of recurrent iconographic elements define the Nilotic motif within the Roman artistic lexicon (Voltan, 2022a). Prominent among these are depictions of the lush and exotic flora characteristic of the Nile region, including lotus blossoms, palm trees, aquatic vegetation, and papyrus reeds (Voltan and Valtierra, 2020). Equally significant is the abundant representation of fauna native to Egypt: crocodiles, hippopotamuses, ibises, ducks, cranes, snakes, mongooses, and a variety of fish and birds populate these scenes (Voltan, 2025). Architectural features also play an essential role in shaping the imagined Egyptian landscape, with towers, pavilions, temples, and enclosures evoking an idealized and somewhat fantastical vision of Egypt (Coarelli, 1990; Voltan, 2022b). Another defining characteristic of Nilotic compositions is the inclusion of human figures, often with ethnographic or satirical undertones. Historical or allegorical personages are frequently substituted by pygmies and dwarves, figures that, while rooted in Greco-Roman traditions of ethnography and humor, play multiple narrative and symbolic functions (Janni, 1978; Dasen, 1993; Meyboom and Versluys, 2006; Strocka, 2021). Pygmies are commonly depicted aboard boats, engaged in activities such as fishing, navigating the waters, or performing rituals. Though less frequent, erotic encounters and scenes with religious connotations also appear within this iconographic corpus (Voltan, 2024). A particularly vivid subset of Nilotic imagery involves dynamic and often comical scenes of combat between pygmies and the region’s dangerous fauna. These depictions exhibit a remarkable variety in both composition and style. The most iconic among them portrays pygmies battling crocodiles, followed by similar confrontations with hippopotamuses and other wild animals. In some instances, pygmies are shown riding atop these creatures, highlighting both their absurdity and their symbolic function (Voltan, 2022c).

The Egyptian motifs, especially the Nile scenes, tend to be found in the more secluded or peripheral areas of Roman domestic architecture, such as triclinia, cubicula, peristyles, and gardens, spaces typically reserved for private use or limited social interaction (Mol, 2013; Barrett, 2019). Their placement away from the main visual axes suggests that these images were intended less for public display than for the intimate enjoyment of household members and select guests. In this context, the distant, exotic landscape of the Nile may have offered a source of aesthetic pleasure, cultural distinction, and playful escapism, reinforcing the Roman viewer’s self-image through contrast with the “other” (Koponen, 2017). In addition to their decorative function, Nilotic scenes, particularly those featuring pygmies, may have held an apotropaic role. Their exaggerated features and comic behaviour, including ithyphallic or macrophallic traits, were believed to ward off the evil eye (malocchio), offering protection through laughter and inversion of norms. Some scholars interpret the pygmy figure itself as an apotropaion, or talismanic presence, embedded within the decorative context (Levi, 1947, pp. 28-34; Spano, 1955, p. 349; Clarke, 2006; Dasen, 2009, p. 226).

Recent research has also highlighted the ongoing evolution of the meaning of these Nilotic images over time. Whereas earlier, Republican-era representations often carried an ethnographic tone, perhaps reflecting genuine curiosity about Egypt, Imperial-period scenes increasingly embraced a burlesque or parodic aesthetic. This shift may have been influenced by the Roman conquest and the ideological need to assert cultural and moral superiority over Egypt and its people (Versluys, 2002, pp. 285-299, 438-439; Tybout, 2003, pp. 508-509; Meyboom and Versluys, 2006, pp. 172-173). As has been argued, the caricatured portrayal of Egyptians as absurd, licentious, or primitive served to reinforce Roman identity through contrast, especially in the aftermath of Augustus’s victory at the Battle of Actium. Finally, another interpretive thread links the Nilotic pygmies with fertility symbolism and sexual potency, underscored by their frequent depiction in overtly sexualized forms. Such representations may have carried auspicious connotations related to abundance, vitality, and the generative powers of nature, qualities associated both with the Nile and with Roman ideals of prosperity (Versluys, 2002, p. 276; Meyboom and Versluys, 2006, p. 173).

3.2. The iconographic and stylistic analysis of the Nilotic painting from Augusta Emerita ^

The central part of the pictorial panel of the natatio contains a series of iconographic elements that allow the scene to be identified as Nilotic (fig. 6). Starting from the bottom, there are four small fish, one of which is only partially preserved, painted in shades of beige and dark brown for the lower and upper parts of the body respectively. They are depicted swimming among aquatic vegetation and lotus flowers. Fish are commonly featured in aquatic representations and form a frequent motif in Nilotic iconography (Voltan, 2025, p. 204). However, the lotus flower holds a particularly prominent role in Egyptian-inspired contexts. Regarded as sacred in ancient Egyptian culture, the lotus symbolized rebirth, owing to its distinctive behaviour of closing its corolla and sinking underwater at dusk, only to reemerge and reopen at dawn, oriented toward the sun (El-Saghir, 1985; Segura and Torres, 2009). In the panel from Augusta Emerita, the lotus is rendered in two colour schemes: green with a central red bud, and pink also with a central red bud. Despite its relative simplicity, the depiction is notable for the graceful forms of the corolla and slender stems, as well as the subtle use of lumeggiature that lend the flowers a sense of depth and plasticity. The stylistic treatment of the lotus here bears a closer resemblance to Nilotic mosaic tradition, such as those in Palestrina (fig. 7) and the Nilotic threshold in the House of the Faun in Pompeii (VI. 12, 2), particularly due to the distinctive central red bud, a detail seldom found in painted Nilotic scenes. The disproportionately large size of the lotus flowers relative to other landscape elements, such as the palm tree, further underscores their symbolic and compositional prominence, possibly emphasizing the riverine setting. The palm tree is another identifiable element in the panel. Although incompletely preserved, its stylized form remains discernible, with an apical tuft and leaves executed in swift brushstrokes, lacking detailed naturalism. Nonetheless, the depiction of the plant’s bark through a series of green dots creates a convincing textural effect. The tree appears to represent a date palm (Phoenix dactylifera), painted in a monochromatic greenish hue and enhanced with lumeggiature. Parallels for this type of rendering can be found in a wall painting from Herculaneum (MANN inv. 8561) (fig. 8) (Voltan, 2023, pp. 39-41) and a frieze in the Temple of Isis at Pompeii (VIII. 7, 28; MANN inv. 8539) (Voltan, 2023, pp. 49-51).

Figure 6. Graphic reconstruction of the painted panel with the Nilotic scene. Elaboration: A. Crespo. ^

Figure 7. Detail from the Nilotic mosaic of Palestrina. From Bernard, 2003, p. 78. ^

Figure 8. Nilotic painting from Herculaneum (MANN, inv. 8651). From Voltan, 2023, p. 39, fig. 3.10. ^

Broadly speaking, the defining feature that identifies the scene as Nilotic is the partially preserved figure of a pygmy. In the Augusta Emerita panel, one leg remains intact, although the foot is missing, along with the phallus and other distinctive accessories (fig. 9). The brown tone of the figure’s skin is similar to other depictions in the wider pictorial repertoire and is made more realistic by the use of lumeggiature to give it volume and plasticity. The prominent representation of the phallus is another significant indicator of the figure’s identity. As already mentioned, pygmies in Nilotic scenes are characterised by exaggerated, often caricatural anatomical features, particularly oversized phalluses, which take on a range of symbolic meanings (Levi, 1947, pp. 28-34; Spano, 1955, p. 349; Clarke, 2006; Meyboom and Versluys, 2006, p. 173). Two additional elements go with the pygmy: a greyish spear, recognisable by its shaft and sharp tip, and a white cloak, whose delicately curved lines suggest movement, as if it were fluttering. The pygmy is otherwise naked, wearing only this cloak, which may be fastened at the shoulders and fluttering behind the figure, like some representations in Pompeian repertoire (fig. 10). This detail is noteworthy, as most pygmies in Nile scenes are depicted completely naked. Clothed figures are rare and include variations such as abdominal bands that leave the phallus visible (House of the Pygmies, IX. 5, 9, Pompeii), short skirts (House of the Doctor, VIII. 5, 24, Pompeii) and tunics of various styles (Sanctuary of Cybele, Lyon) and, in exceptional cases, full armour (House of the Coloured Capitals, VII. 4, 31, Pompeii). However, the corpus of Nilotic representations does not contain any known examples of a cloak similar to the one preserved on the panel from Augusta Emerita (Versluys, 2002; Voltan, 2023). Another distinctive feature is the position of the pygmy directly above a lotus flower, an iconographic arrangement not previously attested in painted Nilotic scenes, although it does appear in mosaics. Examples include the Nilotic mosaics of Vigna Maccarani (MNR inv. SSBAR 171; Versluys, 2002, pp. 76-77) (fig. 11), of Collemancio (MNR inv. 124698; Versluys, 2002, pp. 173-174) and the mosaic of Neptune in Itálica (fig. 12) (Blanco and Luzón, 1974; Mañas, 2009, pp. 179-198; Versluys, 2002, pp. 204-205). Even though there’s a chance that similar iconographic patterns existed in painting at some point, no examples of this type have survived. Still, the panel highlights the importance of common iconographic models and the sharing of sketchbooks between painters and mosaic artisans in ancient times.

Figure 9. Detail of the Nilotic painting in situ. Photo: S. Feijoo Martínez. ^

Figure 10. Painting of Apollo with cloak, Silverware House, VI, 7, 20, Pompeii. Photo: © Jackie and Bob Dunn www.pompeiiinpictures.com. ^

Figure 11. Nilotic mosaics from “Vigna Maccarani” (MNR inv. SSBAR 171). Photo: © https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3a/0_Mosa%C3%AFque_%C3%A0_sc%C3%A8ne_mytholgique_-_villa_Severi_-_Pal._Massimo_3.JPG ^

Figure 12. Mosaic of Neptune, Itálica. Photo: © https://www.museosdeandalucia.es/web/conjuntoarqueologicodeitalica/-/mosaico-de-neptuno ^

Finally, the preliminary analyses carried out by the Centro de Conservación y Restauración de Bienes Culturales of the Junta de Extremadura on the pigments used in the background are particularly noteworthy. A comparative study of various photographs indicates the use of two distinct shades of blue: a darker tone in the lower section and a lighter one in the upper. The darker pigment appears to be azurite, a copper-based blue pigment known since ancient Egyptian times, though seldom employed due to its tendency to degrade over time. In the case of Augusta Emerita, the azurite—likely imported from Egypt—seems to have been partially mixed with black. The identification of the lighter pigment remains inconclusive: standard tests for Egyptian blue have yielded negative results, although false-colour infrared imaging suggests its possible presence. While these findings are still preliminary, they offer valuable insights and contribute meaningfully to the ongoing technical analysis of the painted panel.

4. Closing remarks ^

Based on the data provided in this paper, the main goal was to analyse and contextualise the Nilotic painting found at number 28 Suárez Somonte street in Mérida, starting from the archaeological context in which it was discovered. As demonstrated in this paper, the archaeological evidence confirms the interpretation of the context as part of a public bath complex dating back to the early 1st century CE. This specific context is key to interpreting the meaning and function of the Nilotic theme within the decorative programme of the building. The interplay between the tangible, physical presence of flowing or gushing water and the immaterial, almost dreamlike depiction of water within the painted Nile scenes is particularly striking. Coupled with the exoticism evoked by the iconographic choices, this interplay serves to enhance the viewer’s sensory and cultural experience within the bath environment. Such themes were not arbitrarily chosen; rather, they played an integral role in shaping the ambiance of the space and in conveying symbolic meanings. A particularly illustrative comparison can be made with the Suburban Baths in Pompeii (70 CE), where the decorative scheme of the natatio features Nile friezes centrally positioned on the eastern and western walls, flanked by panels depicting a marine deity surrounded by aquatic fauna in the lower register (Versluys, 2002, pp. 152-154; Voltan, 2023, pp. 145-146). Additionally, scenes of naumachiae adorn the northern and southern walls. This elaborate visual program suggests a carefully curated iconographic narrative in which the sea, the Nile, and the baths are interwoven through the use of imagery. Other examples from Pompeii can also be cited in support of this interpretative approach. In the nymphaea F and G of the Stabian Baths (70 CE), there were paintings with a Nile theme which, although no longer visible today, are preserved in the descriptions of Minervini (1856, pp. 33-40) (Versluys, 2002, pp. 124-125; Voltan, 2023, pp. 101-102). Another noteworthy example is the Sarno Baths (70 CE), where friezes with a Nile theme run along the north, east and west walls of the frigidarium (Versluys, 2002, pp. 124-125; Salvadori and Sbrolli, 2018; Voltan, 2023, pp. 112-115). Such a visual dialogue underscores the thematic and symbolic connections between these elements, reinforcing the notion of water as a multi-dimensional symbol, of purification, of leisure, and of social interaction. As Seneca famously noted, referring to the bustling atmosphere of Roman baths: “Ecce undique me varius clamor circumsonat. Supra ipsum balneum habito” (Sen. Ep. 56.1–3). However, it is important to recognize that the baths, while a place of pleasure and social gathering, also carried connotations of vulnerability in the ancient imagination. It was perceived as a space where one might fall prey to malevolent forces, such as the evil eye or magical incantations (Dunbabin, 1989). In this context, the inclusion of a Nilotic repertoire, featuring, among other elements, comic and grotesque pygmies, served not only a humorous or burlesque function but also an apotropaic one. These diminutive figures were believed to act as guardians, warding off harmful influences and protecting bathers from supernatural threats.

Furthermore, the discovery and subsequent study of this painting have contributed significantly to broadening our understanding of Nilotic iconography in the context of Roman Hispania. Although several examples of Nilotic-themed mosaics have been documented on the Iberian Peninsula, particularly at sites such as Italica, Puente Genil and Mérida, the presence of this motif in wall painting was previously limited to a single known case: the Cartagena frieze, dated to the first half of the 2nd century CE (Velasco and Iborra, 2020; Voltan, 2023, pp. 189-190). The panel from Augusta Emerita is therefore not only earlier than the example from Cartagena but is currently the oldest known pictorial representation of the Nile theme in Spain and one of the oldest in the Roman world. Indeed, most of the surviving Nilotic paintings have been dated to the second half of the 1st century CE (Voltan, 2023, pp. 203-204), highlighting the exceptional importance of the find of Mérida.

In addition, iconographic and stylistic analyses of the painting revealed a strong influence from the compositional patterns typically associated with mosaic artwork, rather than the established pictorial models of Nile scenes. Although it is possible that similar pictorial models existed in the past but have not yet been discovered, this observation draws attention to the permeable boundaries between different artistic media in Antiquity. It also points to the likelihood that shared visual resources, such as pattern books or sketchbooks, circulated among painters and mosaicists, facilitating the mutual contamination of motifs and techniques between different artisans’ fields.

Hence, this paper provides a little but valuable insight into the wider understanding of Nilotic iconography in the visual culture of the Roman world. By exploring the painting in relation to its original archaeological, architectural, and cultural context, this research allows for a more nuanced re-evaluation of the symbolic function, transmission, and reception of Nilotic imagery. In doing so, it also sheds light on the dynamic mechanisms of artistic adaptation, reinterpretation and cross-media exchange that were an integral part of Roman decorative practices, revealing how such motifs were continually reshaped to meet the aesthetic, social and ideological needs of their specific contexts.

Acknowledgements ^

We would like to thank Dr Miguel Ángel Ojeda of the Centro de Conservación y Restauración de Bienes Culturales of the Junta de Extremadura for analysing the pigments used in the painting examined and for all the information provided.

We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback on the paper.

Authors’ contributions ^

- Conception and design: EV, SFM

- Data analysis and interpretation: EV, SFM

- Paper writing: EV, SFM

- Paper critical review: EV, SFM

- Data set: EV, SFM

- Paper final approval: EV, SFM

References ^

Acero, J. (2011) “Augusta Emerita”, in Remolà, J.A. and Acero, J. (eds.) La gestión de los residuos urbanos en Hispania. Xavier Dupré Raventós (1956-2006). In Memoriam, Anejos de Archivo Español de Arqueología, LX. Mérida: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, pp. 157-180.

Acero, J. (2013) “Provincia Lusitania”, in Escudero, F. and Galve, M.P. (eds.) Las cloacas de Caesaraugusta y elementos de urbanismo y topografía en la ciudad antigua. Incluye un estado de la cuestión de las cloacas de Hispania. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando El Católico, pp. 402-409.

Alba, M. (2004) “Arquitectura doméstica”, in Dupré Raventós, X. (ed.), Las capitales provinciales de Hispania. Vol. 2. Mérida. Colonia Augusta Emerita. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider, pp. 67-83.

Álvarez Martínez, J.M. (2004) “Aspectos del urbanismo de Augusta Emerita”, in Nogales, T. (ed.) Augusta Emerita. Territorios, espacios, imágenes y gentes en Lusitania romana, Monografías Emeritenses, 8. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, pp. 129-169.

Álvarez Martínez, J.M. (2008) “Los primeros años de la colonia Augusta Emerita. Las obras de infraestructura”, in La Rocca, E., León, P. and Parisi Presicce, C. (eds.) Le due patrie acquisite. Studi dedicati a Walter Trillmich, Bulletino della Commisione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, Supplementi, 18. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider, pp. 27-40.

Álvarez Martínez, J.M. (2011) “Obras públicas e infraestructuras en la colonia Augusta Emerita. Puentes y acueductos”, in Álvarez Martínez, J. M. and Mateos, P. (eds.) Actas del Congreso Internacional 1910-2010. El yacimiento emeritense. Mérida: Ayuntamiento de Mérida, pp. 265-283.

Álvarez Martínez, J.M. and Nogales, T. (2010) “Los primeros años de la colonia Augusta Emerita: la planificación urbana”, in Gorges, J.G. and Nogales, T. (eds.) Origen de la Lusitania romana (siglos I a.C. – I d.C.). VII Mesa redonda Internacional sobre la Lusitania Romana. Toulouse/Mérida: Museo Nacional de Arte Romano de Mérida, pp. 527-557.

Álvarez Martínez, J.M. and Nogales, T. (2011) “Las producciones pictóricas y musivas emeritenses”, in Álvarez Martínez, J.M. and Mateos, P. (eds.) Actas del Congreso Internacional 1910-2010. El yacimiento emeritense. Mérida: Ayuntamiento de Mérida, pp. 463-488.

Arce Martínez, J. (2004) “Introducción histórica”, in Dupré Raventós, X. (ed.) Las capitales provinciales de Hispania. Vol. 2. Mérida. Colonia Augusta Emerita. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider, pp. 7-13.

Barrett, C. E. (2019) Domesticating empire: Egyptian landscapes in Pompeian gardens. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bernard, A. (2003) Antike Bildmosaiken. Berlin: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Blanco, A. and Luzón, J.M. (1974) El mosaico de Neptuno en Itálica. Sevilla: Patronato del Conjunto Arqueológico de Itálica.

Blázquez Cerrato, C. (2010) “El proceso de monetización de Lusitania desde el siglo I a.C. al siglo I d.C.”, in Gorges, J.C. and Nogales, T. (eds.) Origen de la Lusitania romana (siglos I a.C. – I d.C.). VII Mesa redonda Internacional sobre la Lusitania Romana. Toulouse/Mérida: Museo Nacional de Arte Romano de Mérida, pp. 405-435.

Bragantini, I. (2006) “Il culto di Iside e l’egittomania antica in Campania”, in De Caro, S. (ed.) Egittomania. Iside e il mistero. Milano: Electa, pp. 159-167.

Capriotti Vittozzi, G. (2006) L’Egitto a Roma. Roma: Aracne.

Castillo Alcántara, G. (2021) Pictura ornamentalis romana: análisis y sistematización de la decoración pictórica y en estuco de Augusta Emerita. Tesis doctoral. Murcia: Universidad de Murcia. Accesible en https://portalinvestigacion.um.es/documentos/622ad806011bba44b55f7218, consulta 10.06.2025.

Clarke, J.R. (2006) “Three uses of the pygmy and the aethiops at Pompeii: decorating, othering and warding off demons”, in Bricault, L., Versluys, M.J. and Meyboom, P.G.P. (eds.) Nile into Tiber: Egypt in the Roman World. III International Conference of Isis Studies. Leiden: Brill, pp. 155-169.

Coarelli, F. (1990) “La pompé di Tolomeo Filadelfo e il mosaico nilotico di Palestrina”, Ktema, 15, pp. 225-251.

Corrales Álvarez, A. (2016) La arquitectura doméstica de Augusta Emerita, Anejos de Archivo Español de Arqueología, LXXVI. Mérida: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

Dasen, V. (1993) Dwarfs in Ancient Egypt and Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dasen, V. (2009) “D’un monde à l’autre. La chasse des Pygmées dans l’iconographie impériale”, in Trinquier, J. and Vendries, C. (eds.) Chasses antiques. Pratiques et représentations dans le monde gréco-romain (IIIe siècle av. - IVe siècle apr. J.-C.). Rennes: Université de Rennes, pp. 215-233.

De Vos, M. (1980) L’egittomania in pitture e mosaici romano-campani della prima età imperiale. Leiden: Brill.

Dunbabin, K.M. (1989) “Baiarum Grata Voluptas: Pleasures and Dangers of the Baths”, Papers of the British School at Rome, 57, pp. 6-46.

El-Saghir, M.M. (1985) The papyrus and the lotus in ancient Egyptian civilization. El Cairo: General Organisation for Government Printing Offices.

Enríquez Navascués, J.J. (2003) Prehistoria de Mérida (cazadores, campesinos, jefes, aristócratas y siervos anteriores a los romanos), Cuadernos Emeritenses, 23. Mérida: Museo Nacional de Arte Romano.

Feijoo, S. (2005) “Las presas y los acueductos de agua potable, una asociación incompatible en la antigüedad: el abastecimiento en Augusta Emerita”, in Nogales, T. (ed.) Augusta Emerita. Territorios, espacios, imágenes y gentes en Lusitania romana, Monografías Emeritenses, 8. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, pp. 171-205.

Feijoo, S. (2006) “Las presas y el agua potable en época romana: dudas y certezas”, in Moreno, I. (ed.) Nuevos elementos de ingeniería romana. II Congreso de las Obras Públicas Romanas. Salamanca: Junta de Castilla y León, Consejería de Cultura y Turismo, pp. 145-166.

Feijoo, S. and Alba, M. (2008) “Consideraciones sobre la fundación de Augusta Emerita”, in Feijoo, S. (ed.) IV Congreso de las Obras Públicas en la Ciudad Romana. Madrid: CITOP, pp. 97-124.

Heras, F.J. (2019) “El territorio de Augusta Emerita un siglo antes de su fundación”, in López Díaz, J.C., Jiménez Ávila, J. and Palma, F. (eds.) Historia de Mérida. Un viaje por la Historia de Mérida. Desde los antecedentes de Augusta Emerita a la contemporaneidad. Mérida: Consorcio de la Ciudad Monumental de Mérida, pp. 269-310.

Hidalgo, L.Á. and Feijoo, S. (2023) “L. Aelius Caesar y Helena Augusta honrados en un mismo monumento de Emerita (Mérida). Nueva edición de HEp 19, 2010, 38”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 227, pp. 286-292.

Janni, P. (1978) Etnografia e mito. La storia dei pigmei. Roma: Edizioni dell’Ateneo & Bizzarri.

Jiménez Ávila, J. and Barrientos, T. (2019) “Mérida y su territorio antes de Augusta Emerita: antecedentes, realidad arqueológica y proyección social”, in López Díaz, J.C., Jiménez Ávila, J. and Palma, F. (eds.) Historia de Mérida. Un viaje por la Historia de Mérida. Desde los antecedentes de Augusta Emerita a la contemporaneidad. Mérida: Consorcio de la Ciudad Monumental de Mérida, pp. 207-268.

Koponen, A.K. (2017) “Egyptian Motifs in Pompeian Wall Paintings in their Architectural Context”, in Moormann, E.M. and Mols, S. (eds.) Context and Meaning, Proceedings of the XII International Congress on Ancient Wall Painting. Leiden: Brill, pp. 125-130.

Levi, D. (1947) Antioch Mosaic Pavements. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mañas, I. (2009) “Pavimentos decorativos de Itálica. Una fuente para el estudio del desarrollo urbano de la ampliación adrianea”, Romula, 8, pp. 179-198.

Mateos, P. (2001) “Augusta Emerita. La investigación arqueológica en una ciudad de época romana”, Archivo Español de Arqueología, 74, pp. 183-208. https://doi.org/10.3989/aespa.2001.v74.153

Meyboom, P.G.P. and Versluys, M.J. (2006) “The meaning of dwarfs in nilotic scenes”, in Bricault, L., Versluys, M.J. and Meyboom, P.G.P. (eds.) Nile into Tiber: Egypt in the Roman World. III International Conference of Isis Studies. Leiden: Brill, pp. 171-208.

Minervini, G. (1856) “Notizia de’ più recenti scavi di Pompei. Terme alla strada Stabiana”, Bulletino Archeologico Napolitano, 103, pp. 33-40.

Mol, E.M. (2013) “The Perception of Egypt in Networks of Being and Becoming: A Thing Theory Approach to Egyptianising Objects in Roman Domestic Contexts”, Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal, 2012, pp. 117-132. https://doi.org/10.16995/TRAC2012_117_131

Nogales, T. and Álvarez Martinez, J.M. (2014) “Colonia Augusta Emerita. Creación de una ciudad en tiempos de Augusto”, Studia Historica. Historia Antigua, 32, pp. 209-247.

Palma, F. (2019) “La fundación de Augusta Emerita. Mérida, los inicios de una fascinante historia”, in López Díaz, J.C., Jiménez Ávila, J. and Palma, F. (eds.) Historia de Mérida. Un viaje por la Historia de Mérida. Desde los antecedentes de Augusta Emerita a la contemporaneidad. Mérida: Consorcio de la Ciudad Monumental de Mérida, pp. 311-353.

Palma, F. and Bejarano, A.M. (2023). La arquitectura termal de Augusta Emerita, Memoria, 4. Mérida: Consorcio de la Ciudad Monumental de Mérida.

Piranomonte, M. (1998) Le Terme di Caracalla. Milano: Electa.

Saquete, J.C. (2011) “Aspectos políticos, estratégicos y económicos en la fundación de Augusta Emerita”, in Álvarez Martínez, J.M. and Mateos, P. (eds.) Actas del Congreso Internacional 1910-2010. El yacimiento emeritense. Mérida: Ayuntamiento de Mérida, pp. 111-124.

Salvadori, M. and Sbrolli, C. (2018) “Repertorio e scelte figurative di una ‘bottega’ di pittori a Pompei: il caso del frigidario delle Terme del Sarno”, in Boschetti, C. (ed.) Mvlta per Æqvora. Il polisemico significato della moderna ricerca archeologica. Omaggio a Sara Santor. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses universitaires de Louvain, pp. 527–545.

Segura, S. and Torres, J. (2009) Historia de las plantas en el mundo antiguo. Bilbao: Publicaciones de la Universidad de Deusto.

Spano, G. (1955) “Paesaggio nilotico con pigmei difendentisi magicamente dai coccodrilli”, Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Memorie della Classe di scienze morali, storiche e filologiche, 8/6. Roma: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, pp. 335-368.

Strocka, V.M. (2021) Pygmäen in Ägypten? Die Widerlegung eines alten Irrtums. Bevölkerte Nillandschaften in der antiken Kunst. Darmstadt: Philipp von Zabern.

Swetnam-Burland, M. (2015) Egypt in Italy. Visions of Egypt in Roman Imperial Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tybout, R.A. (2003) “Dwarfs in discourse: the functions of Nilotic scene and other Roman Aegyptiaca”, Journal of Roman Archaeology, 16, pp. 505-515. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759400013374

Velasco, V. and Iborra, F.J. (2020) “Una posible escena nilótica”, in Fernández Díaz, A. and Castillo Alcántara, G. (eds.) La pintura romana en Hispania. Del estudio de campo a su puesta en valor. Murcia: Editum, pp. 133-141.

Versluys, M.J. (2002) Aegyptiaca Romana. Nilotic Scenes and the Roman Views of Egypt. Leiden: Brill.

Voltan, E. (2022a) “Visioni d’Egitto. I topoi iconografici della terra egizia nella pittura romana”, in Harari, M. and Pontelli, E. (eds.) Le cose nell’immagine. Roma: Quasar, pp. 261-271.

Voltan, E. (2022b) “De la piedra a la iconografía. Materiales pétreos y arquitecturas pintadas en los paisajes de Egipto: el caso de los picta nilotica romana”, in Azofra, E., García-Talegón, J. and Gutiérrez-Hernández, A.M. (eds.) La piedra en el patrimonio monumental. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca, pp. 231-241.

Voltan, E. (2022c) “Riding the alterity. The depiction of pygmy ‘warriors’ in Roman Nilotic paintings”, OTIVM. Archeologia e Cultura del Mondo Antico, 13, pp. 1-30. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10283905

Voltan, E. (2023) Picta Nilotica Romana. L’elaborazione e la diffusione del paesaggio nilotico nella pittura romana. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Voltan, E. (2024) “Towards the construction of an identity. Some observations about the pygmies in Roman representations of the Nilotic landscape”, in Cristilli, A., Di Luca, G., Gonfloni, A., Sofia Capra, E., Pontuali, M. (eds.) Experiencing the Landscape in Antiquity 3, BAR Internacional Series, 3178. Oxford: BAR Publishing, pp. 151-156.

Voltan, E. (2025) “Evocación de Egipto. Algunas consideraciones sobre la representación de ciertos tipos de fauna en las pinturas nilóticas de época romana”, Pyrenae, 56, pp. 195-217. https://doi.org/10.1344/Pyrenae2025.vol56num1.6

Voltan, E. and Valtierra, A. (2020) “Et palmae arbor valida. Alcuni spunti sull’iconografia della palma nella pittura nilotica romana”, Eikón Imago, 15, pp. 593-613.