Evidence of late Roman glass production in Southern Lusitania (Ossonoba, Faro, Portugal)

Evidencias de producción de vidrio en época tardoantigua en el sur de la Lusitania (Ossonoba, Faro, Portugal)

José Alberto Retamosa

Departamento de Prehistoria y Arqueología

Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Granada

Campus de Cartuja s/n, 18071 Granada

jose.retamosa@ugr.es  0000-0002-8976-794X

0000-0002-8976-794X

(Corresponding author)

David Govantes-Edwards

INCIPIT – CSIC

Edificio Fontán, Monte Gaiás s/n

15707 Santiago de Compostela

david.govantes-edwards@incipit.csic.es  0000-0003-3998-2200

0000-0003-3998-2200

Adolfo Fernández Fernández

Grupo de Estudios de Arqueología, Antigüedad y Territorio (GEAAT)

Universidad de Vigo

Rúa Canella da Costa da Vela s/n

32004 Ourense

adolfo@uvigo.es  0000-0003-2981-6604

0000-0003-2981-6604

Alba A. Rodríguez Nóvoa

Grupo de Estudios de Arqueología, Antigüedad y Territorio (GEAAT)

Universidad de Vigo

Rúa Canella da Costa da Vela s/n

32004 Ourense

alba.antia.rodriguez.novoa@uvigo.gal  0000-0001-8577-212X

0000-0001-8577-212X

Ricardo Costeira da Silva

Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies (CEIS20)

Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Coimbra

Instituto de Arqueologia, Rua de Sub-Ripas

3000-395 Coimbra

rcosteiradasilva@gmail.com  0000-0003-1006-8562

0000-0003-1006-8562

Paulo de Oliveira Botelho

Engobe – Arqueologia e Património Lda.

Rua do Segeiro 11

7000-672 Évora

paulo.botelho@engobe.pt  0009-0002-4738-987X

0009-0002-4738-987X

Fernando P. Santos

Engobe – Arqueologia e Património Lda.

Rua do Segeiro 11

7000-672 Évora

fernando.santos@engobe.pt  0009-0000-3140-0072

0009-0000-3140-0072

Fecha recepción: 22-04-2025 | Fecha aceptación: 09-08-2025

Abstract The excavation of numbers 32 and 34 on Calle Francisco Barreto, in Faro (Portugal), in 2017, identified some of the remains of a 2nd-century AD fish-salting factory in the industrial area of Ossonoba. Once this factory ceased operating, its structures were given other uses until their final abandonment in the 6th century AD, including the construction of a glass furnace in the central courtyard, found in association with glass-working remains and glass vessels. The typological study of the glass and the related pottery dates the activity of the furnace from the early to the mid-5th century. The results of the chemical analysis (EMPA and LA-ICP-MS) of several glass samples taken from both vessels and glass-working waste are in line with the chronology based on typology, which has made it possible to confirm the dating provided by the typological study and determine the Egyptian and Levantine Mediterranean origin of the glass worked at the furnace. The evidence clearly indicates that glass-working at the complex only began after the fish-salting facility had ceased operating.

Keywords Ossonoba, Faro, Portugal, 4th-5th centuries AD, Late Roman glass production, Glass furnace, Glass production waste.

Resumen En el año 2017, excavaciones desarrolladas en los números 32-34 de la calle Francisco Barreto, en Faro (Portugal), permitieron documentar parcialmente una factoría de salazones del siglo II d.C. asociada al ámbito urbano pesquero-conservero de la romana Ossonoba. Tras el cese de la actividad fabril en el siglo IV d.C., las instalaciones fueron reaprovechadas para otros fines hasta su total colmatación a mediados del siglo VI d.C. Un horno para el soplado de vidrio ha sido constatado en el patio central del inmueble, así como desechos derivados de la actividad vidriera y recipientes también en vidrio. El estudio formal tanto del contexto vítreo como de los materiales cerámicos asociados a la piroestructura han permitido datar su construcción y desuso entre inicios y mediados del siglo V d.C. Muestras de recipientes y desechos de producción de vidrio han sido sometidos a análisis arqueométricos (EMPA y LA-ICP-MS), lo que ha permitido reafirmar la datación proporcionada por el estudio tipológico y determinar el origen egipcio y levantino mediterráneo del vidrio trabajado en el horno. Asimismo, los indicios permiten asegurar que la actividad vidriera comenzó con posterioridad al cese definitivo de la actividad fabril pesquero-conservera en el edificio.

Palabras clave Ossonoba, Faro, Portugal, IV-V d.C., producción de vidrio tardorromano, horno de vidrio, desechos de producción vidriera.

Retamosa, J.A., Govantes-Edwards, D., Fernández Fernández, A., Rodríguez Nóvoa, A.A., Silva, R.C., Botelho, P.O. y Santos, F.P. (2025): “Evidence of late Roman glass production in Southern Lusitania (Ossonoba, Faro, Portugal)”, Spal, 34.2, pp. -256. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/spal.2025.i34.20

Captions List

Figure 3. General view of the paved central courtyard (space VI) and detail of the glass furnace.

Tables List

Table 1. Brief typological description of the objects sampled for the chemical analysis.

Table 2. Precision and accuracy of the EMPA and LA-ICP-MS analysis.

1. Introduction ^

Ossonoba, modern Faro (Portugal), the capital of the region of Algarve, was one of the most important harbours in the Roman province of Lusitania. Owing to its location in the southernmost tip of the Bay of Cadiz, the city has long played a pivotal role in the mercantile traffic between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.

Although rescue archaeology in the city in recent decades has been very active (Viegas, 2011, pp. 81-98), some aspects of the Roman city’s urban layout remain unclear. However, the information available suffices for a tentative reconstruction of the urban topography of Ossonoba (e.g. Viegas, 2011, p. 98, fig. 26; Bernardes, 2014, p. 357, lám. 2; Mantas, 2016, p. 41, fig. 8). The monumental sector of the city (fig. 1), including the forum (current Largo da Sé), the political and administrative centre of the civitas, sat on the hill outlined by the medieval urban wall. The expansion of the city beyond the boundaries of its original nucleus began in the first half of the 1st century AD, although its urban layout did not fully crystallise until the second half of the first century or the early 2nd century (Bernardes, 2011, pp. 13-14). It was then that the city sprawled towards the west and the shoreline, with the emergence of an active production district, mostly devoted to the processing of fish products (Bernardes, 2011, pp. 19-20; Bernardes, 2014, p. 357). This is the context of the remains found in the numbers 32-34 of the Rua Francisco Barreto in 2017, during the rescue excavations undertaken prior to the construction of a hotel (fig. 1).

Figure 1. A: Location of the excavation in the urban layout of modern Faro; B: monumental sector of Ossonoba, including the forum. ^

The excavation, which covered an area of nearly 400 m2 in size, identified two well-differentiated occupation phases. The most recent occupation phase corresponds to a cetaria, a facility for the processing of fish products, with, at least, eight salting vats arranged around a central courtyard. This production area, which has only been partially excavated, includes other smaller spaces (some of which were paved with opus signinum) and a furnace used to work glass which began operating after the cetaria had been abandoned. This article specifically focuses on the glass workshop, the material remains of glass-working found in association with it (drops, moils, threads, etc.), and the archaeometric study of a small number of glass samples; and attempts to relate this material evidence to certain aspects of the historical and cultural context surrounding glass production and consumption in the late Roman period in the south of the Lusitania.

2. Archaeological context and chronology ^

The complexity of the site, both in terms of its stratigraphy and the wide range of materials recovered, has required a prolonged and multi-stage process of study and publication. As a result, several of the contributions cited throughout this article, co-authored by researchers involved in the present study, are already in the final stages of publication and have been referenced here due to their direct relevance to the interpretation of the archaeological evidence.

Although the existence of a residential area cannot be completely ruled out, it seems clear that the main function of the building was the processing of fish products. To date, two occupation phases have been established, dated to the early and late imperial periods respectively. The construction of this fish-salting facility is dated to the mid-2nd century (Silva et al., in press), but the abandonment levels of the factory have yielded large quantities of late fine wares and a smaller number of imported amphorae. The imported fine wares include mostly ARS wares, followed by lamps, DSP, and LRC wares, the chronology of which stretches into the central decades of the 6th century (Fernández Fernández et al., in press). However, the factory appears to have been abandoned earlier, as suggested by the materials found in a well or pit found in the northern sector of the compound (Rodríguez Nóvoa et al., 2024), dug when the factory was no longer active. Therefore, although the material found covers a longer chronological span, the abandonment of the fish-salting factory is dated to the early 5th century (Fernández Fernández et al., 2024).

The factory is arranged around a central courtyard (space VI) paved with laterae (UE=US 847) (figs. 2 and 3), in the centre of which a circular structure with clear traces of combustion, (UE 728), identified as a glass furnace, was built once the factory had ceased operating. The dating of the furnace relies on the stratigraphic sequence of space VI and nearby areas. Particularly important are the levels associated with the abandonment of the fish-salting complex, which predates the furnace, where some bricks from the factory’s courtyard were reused. The ante quem date for the end of the furnace’s activity is given by the layers that seal the site, overlying the furnace.

Figure 2. Final plan and sections of space VI in the fish-salting complex, including the glass furnace. ^

Figure 3. General view of the paved central courtyard (space VI) and detail of the glass furnace. ^

The contexts that correspond to the construction and use of the factory are dated to the early imperial period (Rodríguez Nóvoa et al., in press). This includes an exceptional context with numerous whole amphorae associated to a foundation trench, dated to the early 2nd century (Fernández Fernández et al., 2023; Silva et al., in press). The fills found inside the salting vats are indicative of the abandonment date and the construction of the furnace, which coincides with the silting of several of the factory’s features, including a well situated to the north of the site.

These latter contexts contained abundant late material alongside earlier material dated to between the 1st and 3rd centuries, which must be regarded as residual (Rodríguez Nóvoa et al., 2024). The fills inside the well near the northern boundary of the site yielded specimens of shapes Hayes 50 (ARS C3), Hayes 59, and Hayes 61A (ARS D1), and Tunisian amphorae Africana II and Africana IIIA (Bonifay, 2004), alongside a large number of Lusitanian amphorae of the Almagro 51C and 51A/B types, Baetican amphorae of the Keay XIX type (Rodríguez Nóvoa et al., 2024), and some specimens of what look like the Keay XXV type imitations from the Martinhal workshop (Bernardes, 2022) (fig. 4). The same applies to the salting vats, with imported wares (ARS and Lusitanian, Baetican, and African amphorae), similarly dated by the presence of shapes Hayes 67A and EM.14 in ARS (fig. 5), together with a large assemblage of common and kitchen wares, both imported and locally/regionally produced. The latter include local imitations of imported shapes Hayes 59, Hayes 61A, and Hayes 67 (fig. 5) (after Barbosa, 2021).

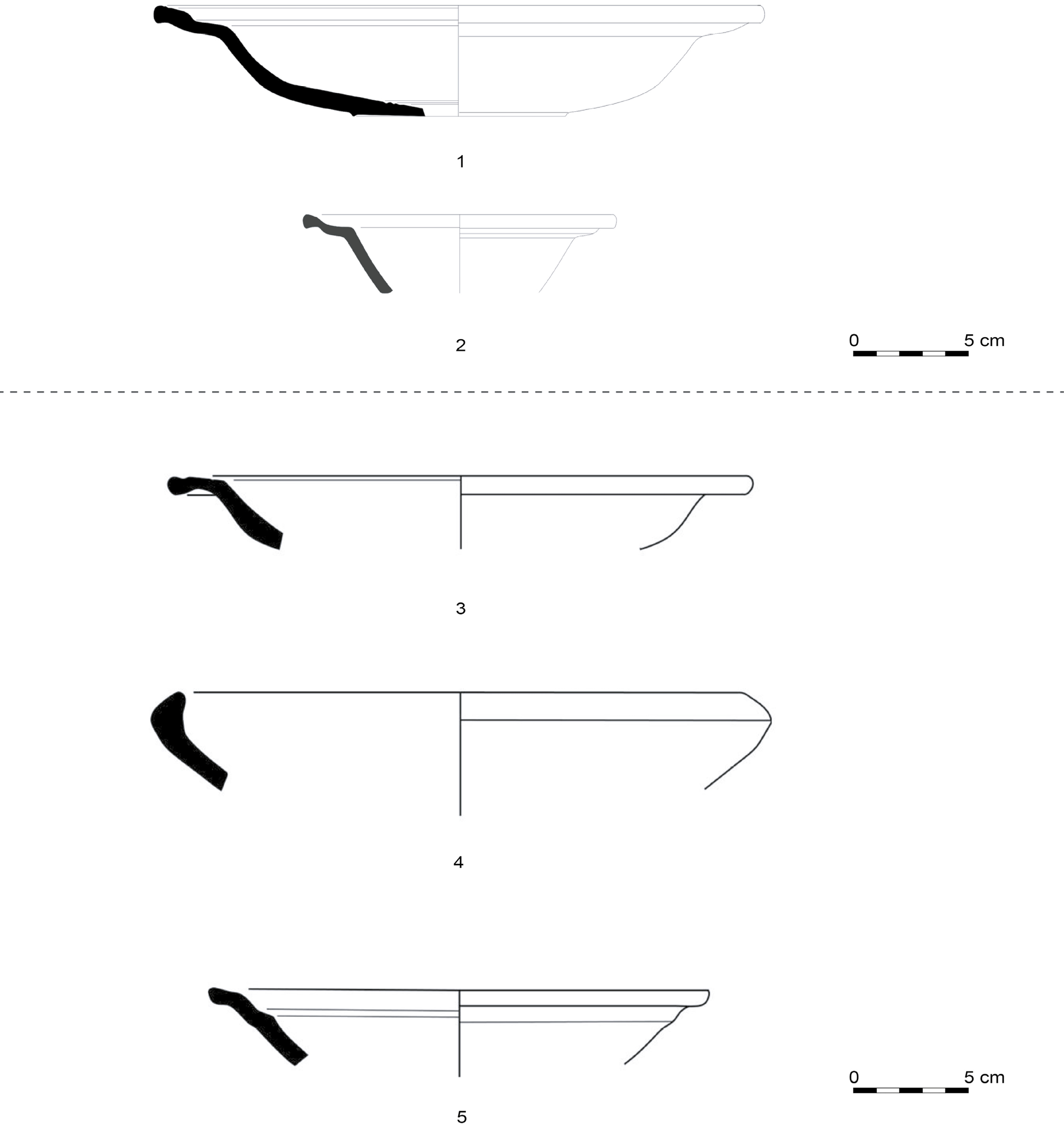

Figure 4. Amphorae from the northern pit/well. 1. Almagro 50 (Lusitania); 2. Almagro 50 (Lusitania); 3. Almagro 51C (Lusitania). 4. Martinhal 1 (Lusitania). 5. Keay XIX (Baetica-Guadalquivir Valley); 6. Keay IIIA (Africa); 7. Keay IIIA (Africa). ^

Figure 5. ARS and local imitations from vats. 1. Hayes 67A; El Mahrine 14 (Mackensen 1997); Local imitation Hayes 9; Local imitation Hayes 61A; Local imitation Hayes 67. ^

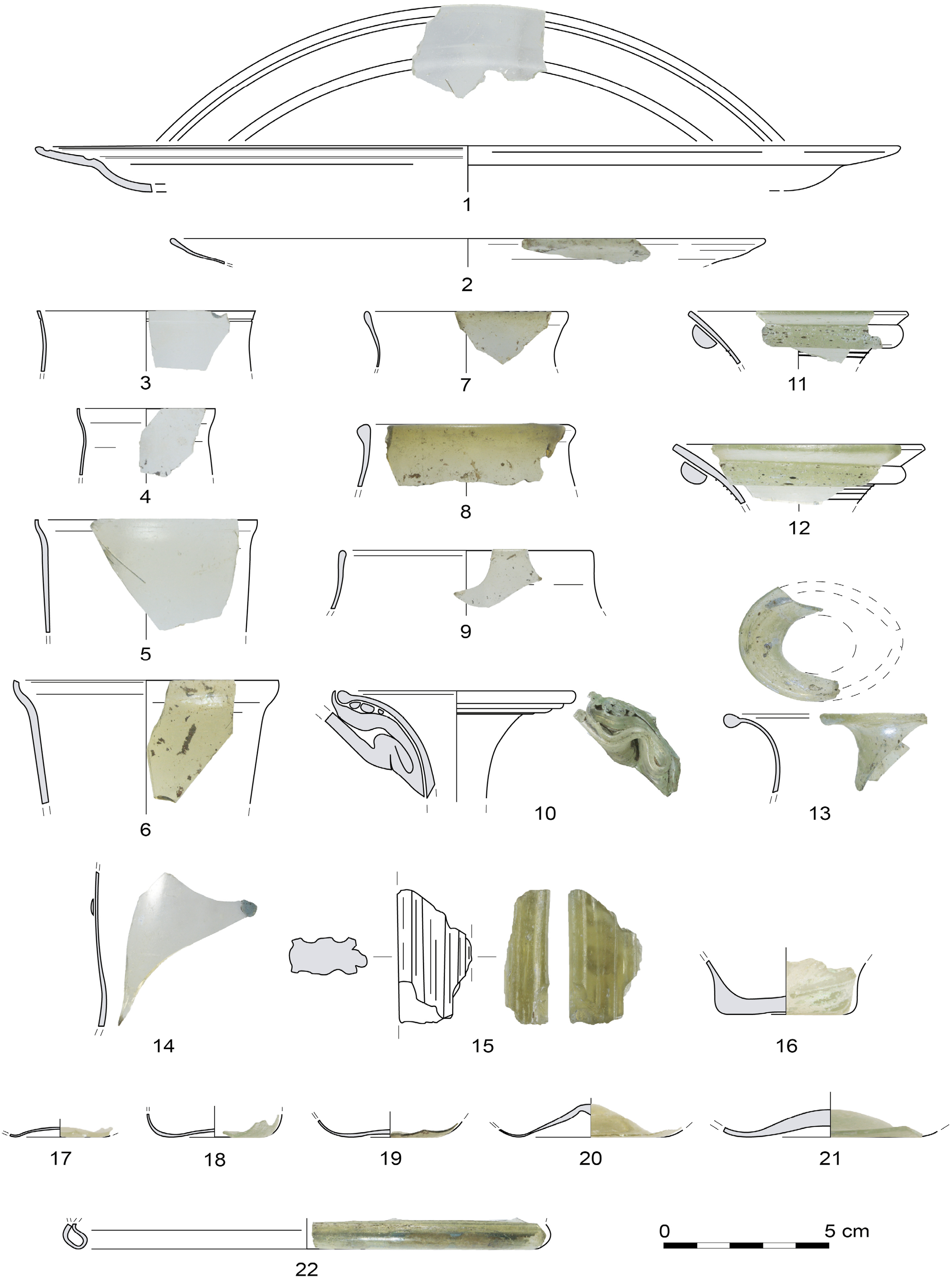

The inside of the vats also yielded glass finds. Some, like with the pottery, must be associated with the remotion of early imperial fills and their deposit during the silting process that followed the abandonment of the factory. For instance, two fragments of plate/bowl shape AR 16 (fig. 6.1-2), the production of which spans the last third of the 1st century and the opening decades of the 3rd century (Fünfschilling, 2015, pp. 472-473, Taf. 10). These residual glass shapes appear alongside shapes that can be dated to the 4th century –especially its second half– and the 5th century: a fragment of bowl or cup with a straight rim and carved line (fig. 6.3) which could belong to types AR 56 and 57, both dated to the 4th century (Fünfschilling, 2015, pp. 485-486, Taf. 28-29); two fragments of a bowl rim with a rounded and thickened edge (fig. 6.4-5), very common in late assemblages from southern and south-eastern Iberia (Sánchez de Prado, 2018, pp. 318-322, 343-348; Retamosa, 2022, pp. 560-564; Retamosa and Expósito, 2024, pp. 134-135), which, especially the largest, can be likened to Feyeux’s (1995, p. 118) shape 81 bowls; three rims with a convex edge and folded lip (fig. 6.6-8), which, owing to their cylindrical-conical profile and small diameter, could correspond to cups Isings 106d or 109, dated between the 4th and the 5th centuries (Isings, 1957, pp. 126-131, 136-139), or to conical lamps of the Foy 11 type, dated to the 5th century (Foy, 1995, p. 197); two narrow-mouthed beakers with overhanging lip (fig. 6.9-10), which, in general, recall bulbous beakers of the Isings 94 type, dated to the 4th century (Isings, 1957, p. 111); the ringless based of a bottle or cylindrical jar with geometric decoration, type Foy 7 (fig. 6.11-12), also dated to the 5th century (Foy, 1995, p. 195); the lower knob of a conical vessel (fig. 6.13), probably a lamp, shape Foy 11 (cita supra); and a fragment of a vessel decorated with cabochons (fig. 6.14), often found in the Iberian Peninsula in contexts dated to the 4th century (especially towards the end of this century) and the first half of the 5th (Sánchez de Prado, 2018, pp. 309-312). Other fragments found are much harder to characterise typologically (fig. 6.15-18).

Figure 6. Glass containers from the fills silting the salting vats: 1-2. Residual AR 16; 3. Foy 2 and AR 56/57; 4-5. possible Feyeux 81; 6-8. possible Isings 106d/109 cups or Foy 11 lamps; 9-10. Ovoidal beakers Isings 94; 11-12. Carved vessels Foy 7; 13. Conical lamp with knob Foy 11; 14. Undetermined container with decorative cabochon; 15-18. Undetermined containers. ^

These materials suggest that the vats were abandoned in the late 4th-early 5th century. It must be pointed out that the fills of the salting vats were found to contain many glass-working remains, which draws a direct link between the activity of the furnace and the abandonment of the vats, setting a fairly solid chronology for the reuse of the courtyard as a glass workshop.

The abandonment of the furnace is marked by the contexts sealing the structure in space VI, specifically UEs 707 and 708, as well as those overlying these, which are found across the whole site. These contexts yielded a large volume of material, including residual pieces from the 1st to 3rd centuries and the late Roman period (4th-5th century).

In addition to the numerous glass-working remains found in the abandonment layers and those directly associated with the activity of the furnace, several vessel fragments were also retrieved, the chronology of which, on typological grounds, spans the early imperial period and perhaps as late as the mid-5th century.

A fragment of shallow plate with a fluted edge, made in colourless glass with a greenish tinge (fig. 7.1), found in UE 707, seems to be an early imperial intrusion; based on its great similarity with other fragments found in Augusta Raurica, particularly two specimens that seem to represent the transition between forms AR 13.1 and 14, the fragments can be dated to the 2nd century, probably to its closing decades (Fünfschilling 2015, p. 471, 5219-5220, Taf. 8). The only open blown shape found in the fill of the interior of the furnace, UE 727, is a bowl with a thickened and rounded rim and convex walls (fig. 7.2). Although similar to the already mentioned Feyeux 81 bowls, this specimen is somewhat eccentric in execution. The type is dated to the 5th and 6th centuries, although some isolated examples have been attested in the following centuries.

Figure 7. Glass vessel fragments related to the abandonment of the furnace and the courtyard: 1. AR 13.1/14 residual plate; 2. Possible Feyeux 81 bowl/plate; 3. Cup with carved line of uncertain typology; 4. Cup or jar of uncertain typology; 5-6. Possible Isings 106d/109 cups or Foy 11 lamps; 7-9. Closed form of uncertain typology; 10-12. Jars or bottles type Foy 12; 13. Cabochon-decorated vessel of uncertain typology; 14. Possible handle; 15. Other fragments of uncertain typology. ^

Closer containers with cracked-off rims include a likely early imperial production: a fragment of rim from a bell-shaped cup with a horizontal carved line, blown in colourless glass and found in the sealing context UE 707 (fig. 7.3); as noted by Alarcão et al. (1976, p. 175), based on Harden and Price (1971, p. 346), these cups are a widespread type between the Flavian period and the early 3rd century. Other cracked-off rims found in contexts UE 707 and UE 708 fit types dated to the 4th and 5th centuries, including small cups and jars (fig. 7.4), and goblets and lamps (fig. 7.5-6), like those found in the salting vats.

Close containers with concave necks or slightly infolding rims include a specimen with a concave neck and a conical rim (fig. 7.7), from one of the layers that cover the courtyard pavement around the furnace (UE 859), which also yielded ceramic fragments dated to the second half of the 4th and the early 5th centuries (Ha. 46, Ha. 52b, Ha. 58, Ha. 59, Ha. 60, Ha 61 and Ha. 67 ARS types with some fragments of ARS in fabric C). However, this and the remaining closed shapes (fig. 7.8-9), with vertical rims and concave walls, probably projecting to form ovoid bodies, blown in a yellowish green glass, are problematic from a chronological perspective. They come from UE 707, which seals the late Roman occupation phase, and they are too small to afford a precise typological identification, which is particularly challenging when it concerns late Roman closed shapes.

Less problematic are the funnel-shaped bottle/jar rims with applied threads found in a fill that cuts into the courtyard pavement (UE 1041) (fig. 7.10), in the top layer of the fill found inside the furnace chamber (UE 835) (fig. 7.11), and in the layer that seals the late Roman phase (UE 707) (fig. 7.12). Typically, these containers and their characteristic decorated rim are likened with type Foy 12, dated to the 5th century (Foy, 1995, p. 192). In the first half, they are generally decorated with thick threads, like our specimen, while in the second half the decoration consists of much finer threads applied forming a spiral around the neck, like those found as residual finds in the overlying levels, dated to the 6th century. A fragment of a cabochon-decorated vessel (fig. 7.13), dated to the late 4th or early 5th century, found in UE 707, must also be regarded as residual. Vessel fragments found in UE 917 (fig. 7.18) and the abandonment levels of the building (fig. 7.14-17 and 19-22) are less informative about the site’s sequence.

Along with these, the ceramic materials, including fine wares and amphorae, found in the dark-coloured layers that seal the late Roman occupation phase, provide an ante quem date for the final abandonment of the area during Antiquity. Their chronology spans the late 5th and the mid-6th century, as suggested by the presence of eastern LRA 1 and LRA 3 amphorae and late amphorae from the Huelva region, common in Atlantic contexts (Fernández Fernández, 2014) and the Algarve (Almeida et al., 2017) from the late 5th and through the 6th century. The fine wares include several specimens of shapes Ha. 3D, Ha. 3E and Ha. 3F in LRC (Hayes, 1972) and shapes Ha. 87C, Ha. 99A/B, Ha. 104A2 (Bonifay, 2004) in ARS (fig. 8).

Figure 8. Late Roman Fine Wares from later/closing levels of the site. 1-4 African Red Slip: 1. Hayes 87C; 2. Hayes 104A2; 3. Hayes 104A2 with poorly stamped decoration (in the centre, a saint or bishop with cross and two female heads at his sides); 4. Hayes 99A/B; 5-6 Late Roman C: 5. Hayes 3F; 6. Hayes 3D. ^

Based on this evidence, the furnace, which was installed in the no longer active fish-processing complex, taking advantage of and reusing its extant structures, seems to have begun operating at some point in the early 5th century and to have been abandoned in an unprecise moment in the middle of the century. Therefore, its use life was relatively short.

3. Traces of glass production ^

3.1. Furnace (figs. 2 and 3) ^

Roman glass-blowing furnaces have sprung all over the territory of the empire, and multiple instances are known, although for the most part our understanding of their construction, like in the Faro example, is limited to their infrastructure. Their basic structure consisted of several elements: a combustion chamber, where the firewood fuel was stoked and fired; a melting chamber, where the glass was melted inside a crucible, from which it was taken by the glassblower with the blowing iron through a small window; and an annealing chamber, where the finished pieces were cooled down slowly to avoid tensions affecting its molecular structure and thus making it more resistant to sudden changes in temperature.

Apart from this basic structure, Roman glass furnaces present considerable variety in terms of sizes (although they must remain relatively small – compared, for instance, to some ceramic kilns – to keep temperature high for a sustained period), materials, and arrangements.

The surviving remains of the furnace in Faro comprise a circular chamber that sits on an existing brick pavement and reuses some of these to line the lower course of the walls. The outer side of the chamber wall was buttressed with yet more bricks. The inner face of the chamber walls is roughly 60 cm in diameter and the height of this lower course of bricks stands c. 25 cm tall. The presence of burning marks on the bricks suggests that this was the lower, combustion chamber.

Concerning the upper structure, we can only speculate, but it is likely to have consisted of a domed structure made of brick or refractory clay (or bricks lined with clay; some of this lining is still preserved on the lower course), with a siege or bench to place the glass crucible or crucibles and, probably, only one window to access the glass. The dome likely had a chimney and vent holes that could be opened or plugged to regulate temperature and air flow. Based on the remains, it is impossible to tell the position of the annealing chamber, whether side-by-side to the blowing chamber, as seems to be the case of the glass furnace preserved in the Isis sanctuary in Cerro del Molinete, in Cartagena (Murcia, Spain) (García-Aboal et al., 2023), or in a top chamber above the blowing chamber, like the glass furnace represented in the famous lamp series dated to the 1st century AD (Lazar, 2006).

3.2. Glass production waste ^

In addition to the furnace, numerous fragments of glass-working waste have been found throughout the stratigraphic sequence of the Roman industrial complex.

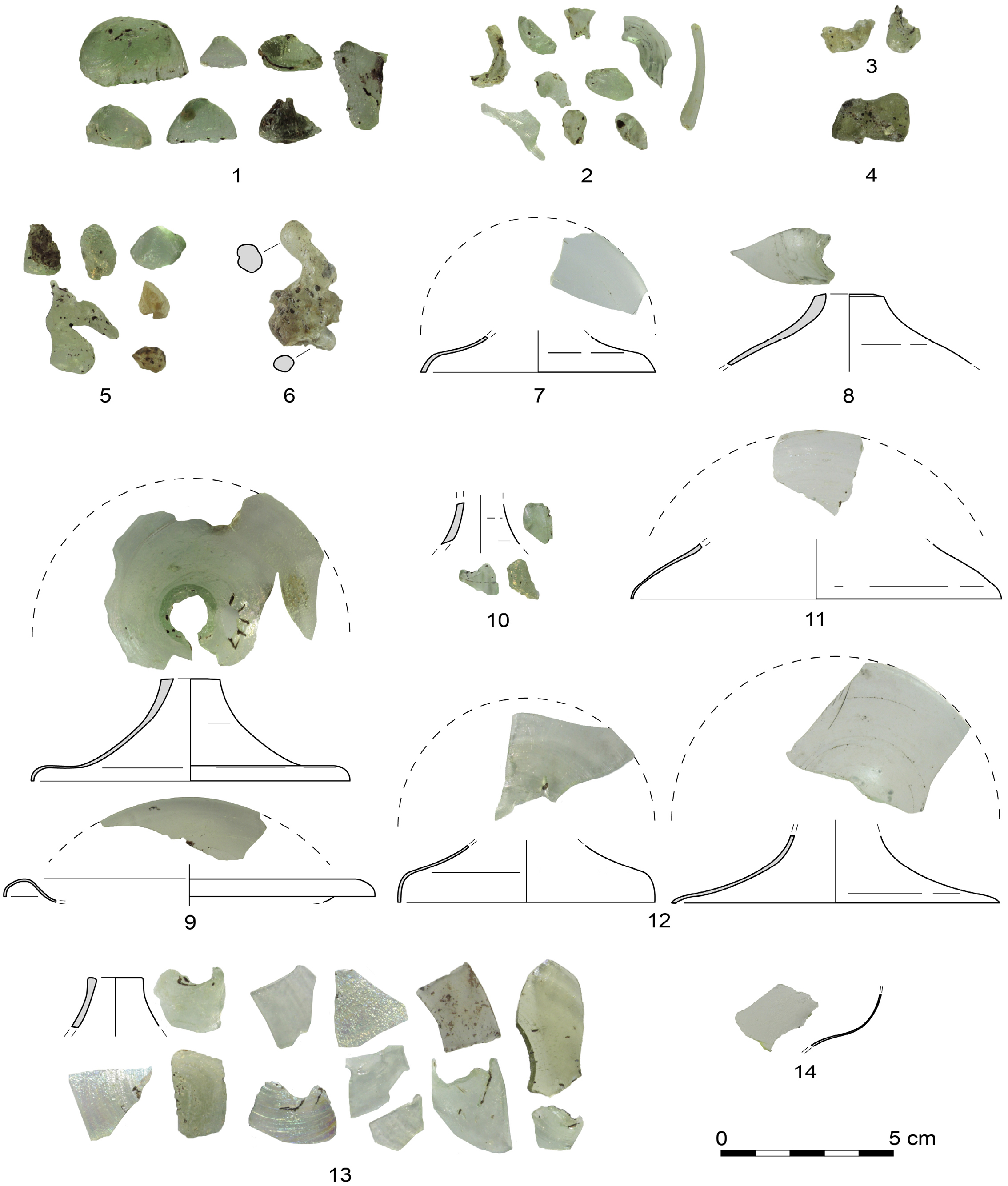

Glass flakes resulting from the fracture of glass chunks were found in several UEs (fig. 9). It is important to note at this stage that research undertaken in recent decades has shown that, throughout the Roman, late Roman, and late antique periods, primary glass (i.e. the production of a glass batch from the raw materials) was for the most part, if not exclusively, as seems increasingly likely, carried out in a limited number of locations near the coast of Syria-Palestine and the Nile Delta in Egypt; this ‘raw’ glass was later exported in chunks to secondary workshops across the empire and beyond for remelting and shaping (Freestone, 2006). All of them are characterised by their polyhedral shape and similar size, c. 1.5 cm in length, although a few are larger, up to 3.4 cm. Except for some intrusive chunks found in UE 1041 —a fill that cuts under the pavement, likely during the construction of the furnace or its operation— these flakes have been found in contexts deposited while the furnace was active, like those that gradually silted the vats —UE 940 and, perhaps, UE 723—, in the abandonment layers documented over the patio and the furnace —UEs 727, 859, and 917—, and the final deposits that seal the underlying sequence —UEs 705, 707, and 877—. Some of these chunks also present some material adhered in the form of a hard brown crust on one side, perhaps the remains of the crucibles where the glass chunks were melted and later solidified. It is impossible to tell whether this material adhered to the glass in the workshops dedicated to the primary production of glass and was traded together with the fresh ‘raw’ glass, or if the adhered material is the result of the solidification of the glass inside a crucible during the re-melting process in the glassblowing workshop discussed here. One block of glass (fig. 9.11), found in UE 846, preserves no adhered material but clear marks of having cooled down in a ceramic container, as confirmed by the spinning wheel marks visible on its underside.

Figure 9. Glassblowing evidence: glass chunks from 1. UE 1041, undercutting the pavement, possible intrusion from later phases; 2. UE 940, filling in vat I; 3. UE 959, filling in vat II; 4. UE 723, overlying the vats; 5. UE 859, overlying the pavement around the furnace; 6. UE 727, fill of the furnace; 7. UE 917, overlying the furnace; 8-9. UEs 877 and 707, sealing the sequence; 10. UE 705, post-abandonment earthworks; 11. UE 846, overlying the bedrock, probably altered in later phases. ^

The remaining traces of glass-working are related to the handling of molten glass to shape objects. These include pseudo-circular fragments of varying thickness (fig. 10.1), which have been potentially identified as glass leftovers from the cutting of stretched-out glass trails; rejected fragments of irregular and curved glass rods used to apply decorative threats (fig. 10.2); irregular blobs, probably drops falling from a molten glass mass (fig. 10.3-6); and several moils (fig. 10.7-14), the crown that remains attached to the blowing iron when the vessel is detached from it to work the rim. The moils are particularly interesting, as the internal diameter of the upper holes correspond to that of the blowpipe, indicating that the blowing irons were between 1 and 1.4 centimetres in inner diameter at the distal end. The diameter of the lower edge of the moils, where the body of the vessel is detached from it, ranges from 6.8 to 10.7 cm, suggesting that they correspond to the blowing of open vessels, maybe cups or lamps (since bowls usually have diameters greater than 10 cm). It is important to emphasise that all these glass-working waste remains were found in deposits directly linked to the silting of the vats, pavement, and furnace, as well as the layers that seal the sequence.

Figure 10. Glassblowing remains: 1-2. possible glass cuts and threads from UE 917, which covered the furnace; 3. Glass drops from UE 945, fill in vat I; 4. UE 722, sealing the vats; 5. UE 917, sealing the furnace; 6. UE 707, sealing the sequence; and glass moils from 7. UE 942, fill in vat I; 8. UE 722, sealing the vats; 9. UE 859, sealing the pavement that surrounds the furnace; 10. UE 727, fill in the furnace; 11. UE 877, sealing the furnace; 12-13. SU 707, sealing the complex; 14. SU 705, post-abandonment earthworks. ^

Waste related to combustion-exposed ceramic materials requires special mention, as they were found in different sectors and contexts across the site. These items can be divided into two groups: fragments of clayey materials in various degrees of crystallisation (fig. 11.1-5), the result of the exposure of the clay to higher temperatures than it can withstand without deforming (Govantes-Edwards, 2025); and tegulae fragments that feature unintentional glass spills, which were found in the fills of fish-salting vats I and II (fig. 11.6-8). The morphological similarities and the crystallisation undergone by the tegulae fragments found in the vats and those found forming the floor of the combustion chamber of the furnace (fig. 11.9) suggest that the former were used in the furnace and eventually replaced and dumped. Alternatively, they could come from another pyrostructure of which no other evidence has been found. Other irregularly-shaped ceramic fragments, perhaps from the furnace lining, could plausibly be interpreted in the same ways. The fact that the activity of the furnace and the fill of the vats seem to be contemporary makes it impossible to know whether these remains are the result of repairs undertaken in the latter or whether they belonged to another furnace.

Figure 11. Glassblowing evidence: crystallised clayey materials from 1. UE 924, early Imperial fill, possibly altered during the late Roman phase of occupation; 2. UE 945, fill in vat I; 3. UE 723, sealing the vats; 4. UE 707, sealing the sequence; tegulae fragments with unintentional glass spills from 5-6. UEs 940 and 942, fill in vat I; 7-8. UE 961, fill in vat II; and 9. detail of in situ crystallised clay and glass spills inside the furnace structure. ^

Except for two fragments – one found in UE 924 and dated by context to the 2nd century AD (although the context also yielded intrusive material from the late Roman period) and another found in UE 945, alongside material dated between the 3rd and the 5th centuries – all of this crystallised material was found in contexts deposited between the mid to late-4th and the early to mid-5th centuries AD. On a balance of probabilities, therefore, the glass waste found inside the vats is likely directly related to the furnace located in the courtyard, and these tegulae fragments be the remains of repairs undertaken in the furnace while it was still active.

The relationship, or lack thereof, of the fragments of glass vessels found in the vats and in the deposits associated with the surroundings and the interior of the furnace, ought to be discussed in connection with the activity of the glasshouse. The chronology of the deposits and the period of activity of the furnace suggests that the workshop is unrelated to the shapes identified as early imperial relicts (vide supra). On the other hand, the moils present a maximum diameter of 10.7 cm smaller than that of some bowls and other large vessels at the rim, although this does not guarantee that these larger forms were not worked at the workshop, only that none of their moils have been found. In any case, the diameter of some of the vessels found does fall within the range attested for the moils, particularly vessels with convex, cracked-off rim (figs. 6.3 and 6.8; fig. 7.3-6); some vessels with thickened, fire-rounded rims (fig. 7.7-9); and even rims of jars or bottles with funnel-shaped mouths and cylindrical neck (fig. 7.10-14).

The colour of the moils and other fragments of production waste (pale blue, pale green, and blue-green) draws no direct connection between this evidence and yellowish green and olive green vessels. This further suggests that the latter (fig. 6.7; figs. 7.6 and 8) were not blown at the furnace.

The presence of these fragments alongside production waste could suggest that these had been collected for recycling, thus finding their way to the vats used as dumps once the activity of the furnace ceased. However, this idea should be taken with caution, because the vats also contained other fragments without relation to the activity of the workshop, perhaps in connection with food consumption nearby.

3.3. The furnace in its wider Mediterranean context ^

At any rate, the Faro furnace seems clearly to reflect a common pan-Mediterranean adaptative reuse phenomenon in Late Antiquity, the installation of glass workshops in existing constructions chosen because of their robustness and, therefore, their ability to withstand high temperatures (Leonne, 2003). In the Iberian Peninsula, this is seen in other sites too, beginning with the above-noted sanctuary of Isis in Cerro del Molinete (García-Aboal et al., 2023); in ancient Acinipo, Ronda (Malaga, Spain), where a glass furnace was built in the 4th century inside an abandoned baths building (Castaño et al., 2009, pp. 70-71); in the Roman city of Suel, modern Fuengirola (Malaga), where a glass workshop was installed in a reused building in the 4th century (Hiraldo Aguilar et al., 2004); in Malaga, a chunk of turquoise glass found in 4th-century contexts in the preserves factory in c/ Cerrojo 24-26, Malaga, was interpreted as glass-working evidence (Pineda de las Infantas Beato, 2002, p. 485), although this interpretation must be regarded as merely tentative; also in Malaga, in the IBN Gabirol gardens, in Rampa o c/ de Alcazabilla, a glass furnace —E.107— was dated to the Late Roman period in sector E’9 (Fernández Rodríguez et al., 2003, p. 745, lám. III), which witnessed significant fish-salting activity between the 3rd and 5th centuries AD (cita supra, p. 742); in Ammaia (Portugal), inside a former defensive tower in the city wall, between the late 4th and early 5th century (da Cruz and Sánchez de Prado, 2015, p. 182); and Valencia (Spain), where a glass furnace was built inside an abandoned commercial building, likely an horreum, at some point between the 3rd and the 5th centuries (Sánchez de Prado, 2014).

On the northern shore of the Strait of Gibraltar and its hinterland, the excavation of a number of fish-salting facilities has yielded some evidence of glass production waste: in Baelo Claudia (Tarifa, Cádiz), stone and ceramic construction material with glassy spills, interpreted as the dismantled remains of a furnace, were documented in deposits that formed during the second half of the 2nd century; in the building known as cetaria X, in contexts dated to the 4th century; and in cetaria XI, between the late 4th and the early 5th century (Retamosa et al., 2020; Retamosa, 2022, pp. 190-191); and in Cerro del Trigo (Doñana, Almonte, Huelva), where some fragments of glass presumably deformed by exposure to high temperatures were located during the excavation of another industrial complex, in abandonment levels dated to between the 4th and the 6th centuries (Campos Carrasco et al., 2014, pp. 100-113). The study of similar remains in the abandonment levels of nearby Roman fish-salting facilities, both in southern Spain and North Africa, is currently under way by the first author of this paper in cooperation with Dr. Darío Bernal-Casasola and the University of Cádiz.

4. Chemical analysis ^

4.1. Material and methods ^

The analyses were carried out with eight samples of glass from several archaeological contexts directly related to the operation of the workshop or that corresponded to contexts with dating potential (the sampling took place while the study of the stratigraphic sequence was under way), in order to try to establish a rough outline of the glass being worked in the workshop within budget. They correspond to seven items (tab. 1 and fig. 12, RAK1 to RAK 7), since two samples were taken out of one object (RAK3) because part of the object looked slightly darker than the rest. Sampling thus prioritised position in the stratigraphic sequence and working waste, to maximise the likelihood of analysing glass worked at the site, instead of imported cullet worked elsewhere and not remelted at the site. The colours of the sampled items included pale olive green, and pale blue.

Table 1. Brief typological description of the objects sampled for the chemical analysis. ^

|

SAMPLE ID |

FRAGMENT |

COLOUR |

OBJECT TYPOLOGY |

PROVENANCE |

EU DATE |

|

RAK1 |

Short and everted rim, slightly tapered walls |

Olive green |

Conical beaker or lamp Isings 106d/109 or Foy 11 |

UE 707 –Deposit sealing the final abandonment of the complex |

Late 5th to mid. 6th AD, residual objects from earlier phases |

|

RAK2 |

Concave base |

Pale blue-green |

Bowl? Indeterminate |

UE 707 –Deposit sealing the final abandonment of the complex |

Late 5th to mid. 6th AD, residual objects from earlier phases |

|

RAK3 (two samples) |

Hollow cylindrical objects, broken upper edge, outfolding projection |

Pale blue |

Production waste Glass nugget from the lower part of a moil |

UE 707 –Deposit sealing the final abandonment of the complex |

Late 5th to mid-6th AD, residual objects from previous phases |

|

RAK4 |

Fragment of pale blue glass thread |

Pale blue |

Production waste Glass thread |

UE 917 Layer related to the rearrangement of the sector after the abandonment of the workshop area |

4th to 5th AD |

|

RAK5 |

Rounded lip, funnel neck, folded handle and spiral-applied thread |

Pale blue |

Jar Foy 12 |

UE 1041 Fill undercutting the pavement of the courtyard, related to the construction of the furnace |

Mid-2nd AD, intrusive materials from early 5th AD or later |

|

RAK 6 |

Fragment of pale blue glass thread |

Pale blue |

Production waste Glass thread |

UE 727 Layer formed after the abandonment of the furnace |

Material from earlier occupation phases mixed with material dated to up the 6th century |

|

RAK7 |

Fragment of pale blue glass thread |

Pale blue |

Production waste Glass thread |

UE 727 Layer formed after the abandonment of the furnace |

Material from earlier occupation phases mixed with material dated to up the 6th century |

Figure 12. Objects sampled for the chemical analysis. ^

The samples were subject to Electron Microprobe Analysis (EMPA) for major and minor elements and Laser Ablation Inductively-Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) for trace elements. For the sampling protocol, mounting of samples, and instrumental setup see Govantes-Edwards et al. (2024).

Table 2 presents precision and accuracy of the EMPA and LA-ICP-MS analysis. The EMPA results for alumina, titanium, manganese, and lead present errors in excess of 10% relative. Therefore, for these elements we shall exclusively use the LA-ICP-MS data. The LA-ICP-MS data for alumina, which is not reflected in the LA-ICP-MS precision and accuracy results, is (after conversion of 10325 ppm average Al into oxide) 1.95% Al2O3, which is barely a 0.03% relative deviation from the 2% nominal content of SRM612 glass (NIST 1992).

Table 3 presents the mean of the three readings taken per sample for EMPA and Table 4 the mean of the readings taken per sample for LA-ICP-MS.

Table 2. Precision and accuracy of the EMPA and LA-ICP-MS analysis. ^

|

CornA (n=18) |

Na2O |

MgO |

Al2O3 |

SiO2 |

TiO2 |

K2O |

CaO |

MnO |

Fe2O3 |

CuO |

PbO |

|

Measured |

14.28 |

2.60 |

0.79 |

66.85 |

0.84 |

2.92 |

5.10 |

1.03 |

0.90 |

1.24 |

0.07 |

|

S.D |

0.34 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.39 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.07 |

0.06 |

0.12 |

0.05 |

0.17 |

|

Published |

14.34 |

2.59 |

0.90 |

66.79 |

0.82 |

2.89 |

5.30 |

1.08 |

0.93 |

1.27 |

0.08 |

|

Error (% relative) |

0.45 |

-0.34 |

11.73 |

-0.08 |

-1.98 |

-1.03 |

3.76 |

4.93 |

3.21 |

2.10 |

14.02 |

|

CornB (n=18) |

Na2O |

MgO |

Al2O3 |

SiO2 |

TiO2 |

K2O |

CaO |

MnO |

Fe2O3 |

CuO |

PbO |

|

Measured |

17.09 |

1.01 |

4.37 |

62.31 |

0.11 |

1.04 |

8.79 |

0.25 |

0.29 |

2.96 |

0.45 |

|

S.D |

0.17 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

0.40 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

0.10 |

0.04 |

0.05 |

0.06 |

0.18 |

|

Published |

17.12 |

1.01 |

4.11 |

61.77 |

0.10 |

1.04 |

9.42 |

0.29 |

0.31 |

2.91 |

0.54 |

|

Error (% relative) |

0.18 |

-0.23 |

-6.43 |

-0.88 |

-13.16 |

0.46 |

6.66 |

13.85 |

7.11 |

-1.56 |

15.83 |

|

NIST 612 (n=3) |

Li |

B |

Ti |

V |

Cr |

Co |

Ni |

Cu |

Zn |

As |

Rb |

|

Measured |

40.2 |

34.7 |

40.76 |

37.9 |

34.8 |

34.1 |

37.6 |

37.1 |

37.0 |

32.7 |

32.2 |

|

S.D |

0.2 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

1.3 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

|

Certified |

40.2 |

34.3 |

44 |

38.8 |

36.4 |

35.5 |

38.8 |

37.8 |

39.1 |

35.7 |

31.4 |

|

Error (% relative) |

-0.1 |

-0.8 |

7.3 |

2.1 |

4.1 |

3.9 |

3.0 |

1.7 |

5.2 |

8.3 |

-2.8 |

|

NIST 612 (n=3) |

Sr |

Y |

Zr |

Sn |

Sb |

Ba |

La |

Ce |

Nd |

Pb |

Th |

|

Measured |

77.8 |

38.4 |

37.7 |

47.5 |

33.2 |

39.5 |

36.1 |

37.6 |

35.2 |

36.1 |

36.6 |

|

S.D |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|

Certified |

78.4 |

38.3 |

37.9 |

38.6 |

34.7 |

39.3 |

36 |

38.4 |

35.5 |

38.6 |

37.8 |

|

Error (% relative) |

0.7 |

-0.3 |

0.2 |

-23.6 |

4.2 |

-0.5 |

-0.2 |

1.8 |

0.6 |

6.3 |

2.9 |

Table 3. EMPA results of the glass from Faro. ^

|

Label |

SiO2 |

Na2O |

K2O |

Fe2O3 |

Al2O3 |

MgO |

PbO |

CaO |

MnO |

TiO2 |

CuO |

Total |

|

RAK1 |

66.12 |

17.90 |

0.43 |

1.68 |

3.78 |

1.07 |

0.02 |

5.60 |

2.42 |

0.81 |

0.014 |

99.88 |

|

RAK2 |

69.82 |

14.50 |

0.65 |

0.26 |

4.03 |

0.59 |

0.01 |

8.20 |

1.29 |

0.08 |

0.011 |

99.50 |

|

RAK3 |

67.95 |

16.80 |

0.69 |

0.22 |

3.56 |

0.56 |

0.00 |

8.37 |

1.23 |

0.05 |

0.013 |

99.51 |

|

RAK3b |

67.06 |

16.50 |

1.15 |

0.22 |

3.51 |

0.59 |

0.00 |

8.40 |

1.26 |

0.07 |

0.008 |

98.89 |

|

RAK4 |

69.66 |

14.69 |

0.65 |

0.31 |

4.07 |

0.59 |

0.01 |

8.20 |

1.24 |

0.08 |

0.021 |

99.59 |

|

RAK5 |

69.41 |

14.87 |

0.50 |

0.88 |

3.39 |

0.57 |

0.02 |

8.61 |

1.16 |

0.05 |

0.003 |

99.48 |

|

RAK6 |

68.75 |

19.15 |

0.45 |

0.51 |

3.07 |

0.78 |

0.00 |

6.65 |

1.16 |

0.14 |

0.034 |

100.74 |

|

RAK7 |

68.99 |

16.75 |

0.55 |

0.74 |

3.43 |

0.74 |

0.17 |

7.16 |

1.07 |

0.10 |

0.001 |

99.74 |

Table 4. LA-ICP-MS results of the glass from Faro. ^

|

Label |

Li |

B |

Al |

P |

V |

Cr |

Co |

Ni |

Cu |

Zn |

As |

Rb |

Sr |

Y |

Zr |

Nb |

Mo |

|||||

|

RAK1 |

3.82 |

150.29 |

15760.81 |

212.43 |

60.79 |

85.18 |

10.83 |

22.04 |

48.61 |

34.15 |

4.81 |

5.47 |

485.22 |

12.73 |

385.31 |

8.21 |

5.37 |

|||||

|

RAK2 |

3.26 |

90.76 |

17378.54 |

408.95 |

15.13 |

10.19 |

6.61 |

7.07 |

35.74 |

17.18 |

3.44 |

9.56 |

505.76 |

7.28 |

35.49 |

1.44 |

5.34 |

|||||

|

RAK3 |

3.06 |

115.59 |

14980.58 |

304.54 |

13.34 |

12.44 |

5.20 |

6.88 |

24.19 |

14.15 |

2.33 |

8.98 |

509.35 |

7.15 |

36.45 |

1.28 |

5.27 |

|||||

|

RAK3b |

3.16 |

86.53 |

17108.44 |

409.41 |

14.64 |

10.16 |

6.10 |

6.82 |

32.40 |

16.74 |

2.94 |

9.35 |

496.58 |

7.22 |

35.14 |

1.39 |

4.91 |

|||||

|

RAK4 |

3.02 |

84.75 |

14693.00 |

314.10 |

13.81 |

10.34 |

3.59 |

7.57 |

6.82 |

12.91 |

2.76 |

7.19 |

458.00 |

6.73 |

35.44 |

1.31 |

4.09 |

|||||

|

RAK5 |

4.47 |

171.69 |

12706.48 |

204.61 |

19.95 |

14.53 |

7.02 |

10.56 |

80.52 |

19.42 |

3.68 |

5.99 |

489.48 |

6.73 |

65.06 |

2.05 |

3.93 |

|||||

|

RAK6 |

8.53 |

145.78 |

14122.86 |

273.27 |

17.15 |

12.59 |

6.24 |

8.63 |

67.89 |

17.12 |

5.91 |

9.44 |

475.34 |

6.79 |

47.90 |

1.77 |

3.85 |

|||||

|

RAK7 |

5.96 |

163.69 |

12885.65 |

208.80 |

18.71 |

14.07 |

6.24 |

7.99 |

66.03 |

17.04 |

3.43 |

6.41 |

471.78 |

6.54 |

61.71 |

1.94 |

3.37 |

|||||

|

Label |

Sn |

Sb |

Cs |

Ba |

La |

Ce |

Pr |

Nd |

Sm |

Eu |

Gd |

Tb |

Dy |

Ho |

Er |

Tm |

Lu |

|||||

|

RAK1 |

1.43 |

0.47 |

0.05 |

328.56 |

12.74 |

20.70 |

2.93 |

11.86 |

2.36 |

0.63 |

2.34 |

0.35 |

2.21 |

0.47 |

1.53 |

0.21 |

0.22 |

|||||

|

RAK2 |

2.27 |

3.30 |

0.09 |

567.31 |

6.65 |

12.91 |

1.61 |

6.45 |

1.42 |

0.43 |

1.37 |

0.21 |

1.27 |

0.26 |

0.72 |

0.10 |

0.09 |

|||||

|

RAK3 |

1.08 |

0.17 |

0.07 |

470.35 |

6.59 |

11.81 |

1.58 |

6.21 |

1.39 |

0.40 |

1.17 |

0.18 |

1.11 |

0.22 |

0.77 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

|||||

|

RAK3b |

1.91 |

3.12 |

0.09 |

521.08 |

6.51 |

12.53 |

1.57 |

6.61 |

1.43 |

0.40 |

1.38 |

0.20 |

1.26 |

0.23 |

0.68 |

0.09 |

0.10 |

|||||

|

RAK4 |

1.03 |

0.90 |

0.07 |

269.74 |

5.90 |

11.24 |

1.42 |

5.87 |

1.15 |

0.37 |

1.10 |

0.17 |

1.15 |

0.22 |

0.65 |

0.08 |

0.09 |

|||||

|

RAK5 |

3.91 |

92.73 |

0.07 |

406.04 |

6.70 |

11.97 |

1.59 |

6.37 |

1.26 |

0.35 |

1.25 |

0.19 |

1.04 |

0.24 |

0.66 |

0.09 |

0.10 |

|||||

|

RAK6 |

12.99 |

26.89 |

0.15 |

364.87 |

6.67 |

12.25 |

1.56 |

6.63 |

1.25 |

0.40 |

1.18 |

0.17 |

1.13 |

0.22 |

0.68 |

0.08 |

0.10 |

|||||

|

RAK7 |

3.49 |

101.76 |

0.08 |

387.72 |

6.40 |

11.76 |

1.54 |

6.11 |

1.23 |

0.37 |

1.13 |

0.18 |

1.14 |

0.25 |

0.65 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

|||||

|

Label |

Hf |

Ta |

Pb |

Th |

U |

|||||||||||||||||

|

RAK1 |

9.03 |

0.51 |

8.79 |

2.75 |

1.41 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

RAK2 |

0.88 |

0.09 |

27.36 |

0.79 |

0.66 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

RAK3 |

0.85 |

0.08 |

6.94 |

0.77 |

0.69 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

RAK3b |

0.85 |

0.09 |

26.11 |

0.72 |

0.66 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

RAK4 |

0.88 |

0.08 |

7.23 |

0.74 |

0.76 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

RAK5 |

1.51 |

0.13 |

31.31 |

1.01 |

0.99 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

RAK6 |

1.27 |

0.10 |

991.30 |

0.93 |

0.83 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

RAK7 |

1.59 |

0.13 |

27.14 |

0.97 |

0.92 |

|||||||||||||||||

4.2. Results ^

All the glass samples analysed are soda-lime-silica glass, in line with known glasses of the late Roman period. The main network former is silica, with results that range from 66.12 to 69.82 wt.% SiO2, and the main flux is soda, with results that range from 14.50 to 19.15 wt.% Na2O. The chemistry of the glass is stabilised with lime, which ranges from 5.60 to 8.61 wt.% CaO. The silica is likely derived from sand, as suggested by the presence of such impurities as iron oxide (0.22-1.68 wt.% Fe2O3) and alumina (2.40-3.28 wt.% Al2O3). On the other hand, strontium levels (458-509 ppm Sr in the assemblage) above 200 ppm Sr point to shell fragments brought in with the sand as the source of lime rather than added calcite (Freestone et al., 2009; Brems et al., 2014). Finally, the fluxing agent used is in all probability so-called natron, fairly pure soda-rich evaporitic salts that dominate glassmaking in the Mediterranean basin and Europe from the early 1st millenium BC to the 8th-9th centuries AD (Shortland et al., 2006). Chemically, this is expressed by the low contents of such impurities as magnesia (0.56-1.07 wt.% MgO) and potash (0.43-1.15 wt.% K2O) in the assemblage, well below the conventional cut-off point of 1.5 wt.% adopted to distinguish between natron- and plant ash-fluxed glasses, following Lilyquist and Brill (1993).

In recent decades, intensive research on the chemical characteristics of Roman and late Roman glass has established a series of compositional groups with increasingly well-known provenances and chronologies. These groups are defined on the basis of the use of different sands (which reflect their geological makeup) and glass recipes (for an overview see Rehren and Freestone, 2015). The compositional groups that can potentially coincide chronologically with the Faro samples include a broad group known as Levantine 1, widely believed to be the result of the mixing of natron and sand from the Belus River, in modern Israel (Brill, 1967), and two groups known as HIMT – for High Iron Manganese and Titanium – and Foy 3.2, characterised by Danièle Foy and co-workers (2003) at the excavation of the Bourse, in Marseilles, both of which are believed to have been made in Egypt.

So-called Levantine 1 glass is characterised by elevated silica (approaching or above 70 wt.% SiO2) and lime (typically 8-10 wt.% CaO), and comparatively low soda (12-16 wt.% Na2O), iron (<0.5 wt.% Fe2O3) and titanium (<0.1 wt.% TiO2). That said, it is important to note that the analysis of glass from a number of primary workshops from different chronologies has identified some changes in the composition of Levantine 1 glasses over time, notably a gradual reduction in the soda to silica ratio in the late Roman and late antique period, as well as a gradual decrease in lime contents and an increase in alumina contents (Freestone et al., 2000). Since these changes can help situate these glasses chronologically, we shall base our comparisons on the glass analysed in the workshops of Jalame, dated to the 4th century (Brill, 1999), and Apollonia, roughly dated to the 6th-7th century (Freestone et al., 2000; 2008). HIMT glass is characterised by higher soda (typically >18 wt.% Na2O) and much higher iron (sometimes above 4 wt.% and rarely below 1.5 wt.% Fe2O3), manganese (typically 1.5-2 wt.% MnO, and sometimes more), and titanium (≈0.5 wt.% TiO2), as well as lower silica (typically 62-65 wt.% SiO2). The Foy 3.2 glass, the chronology of which spans the 4th and 6th centuries, is similar to HIMT, although it presents lower amounts of iron, manganese, and titanium, for which reason it has sometimes been referred to as weak HIMT (Rehren and Rosenow, 2020). HIMT glass became the dominant glass type in the Mediterranean basin and Europe in the 4th and 5th centuries (Freestone et al., 2018).

Four of the objects sampled in Faro (RAK2, RAK3, RAK4, and RAK6), one of which comes from a vessel fragment, while the other three come from production waste, present alumina to silica and titania to alumina ratios (which are indicative of the geological makeup of the sands used to make the glass) typical of Levantine glasses (see fig. 13), and their soda and silica contents are also within ranges compatible with this provenance. Two other samples (RAK5 and RAK7), a vessel fragment and a fragment of production waste, while presenting strong affinities to Levantine 1 glass (e.g. elevated silica and alumina), present higher sand-borne detritic impurities (e.g. iron and titania) than is typical in Levantine 1 glasses, as well as elevated Zr (Rosenow and Rehren, 2014), suggesting that these glasses are a mixture of Levantine 1 and Egyptian glasses, likely of the Foy 3.2 type. In this regard, RAK6 also presents elevated iron and fairly high titania for a Levantine glass, so a degree of mixing cannot be ruled out. The compositions of RAK3 and RAK3b are fairly similar except for the potash content, which is nearly double in the latter than in the former, perhaps the result of some contamination from fuel ashes in the darker area, which also presents higher phosphorus. A degree of furnace contamination probably also explains the higher alumina content of the sample taken from the darker area. RAK1 (a vessel fragment), in addition to a soda to silica ratio typical of Egyptian glasses, presents fairly high iron, manganese, and titanium, situating it squarely with the HIMT group. The characteristic olive-green colour of this vessel is due to these iron impurities.

Figure 13. Alumina to silica and titania to alumina ratios of the Faro glasses, compared with a number of coeval known compositional groups. Data for Levantine 1, Jalame workshop, from Brill (1999); data for Levantine 1, Apollonia workshop, from Freestone et al. (2000; 2008); data for HIMT and Foy 3.2 from Foy et al. (2003). ^

In addition to this, RAK5, RAK6 and RAK7 present small but significant contents in certain chromophores and opacifiers, such as antimony (26 to 101 ppm Sb), and lead (991 ppm Pb in RAK6), the presence of which above natural thresholds is often used to argue for recycling practices in naturally-coloured glasses (Freestone, 2015; Paynter and Jackson, 2016; Duckworth, 2020). The thresholds used here are based on data from glass believed not to have undergone recycling, and are relatively conservative, that is, high: 50-100 ppm Cu; 50-75 ppm Pb; 25 ppm Sn; 10-20 ppm Sb (after Rehren and Brüggler, 2015).

As illustrated by figure 14, the samples identified as Levantine (mixed or unmixed) present a relatively widespread in terms of the oxides used to distinguish between different Levantine productions. In these circumstances, it is not possible to associate these glasses with a specific workshop with any certainty (there is also that the productions from the workshops sometimes overlap significantly, so in this regard extra caution is needed), although they are more akin to the Jalame productions, which is in line with the chronology of operation of the workshop.

Figure 14. The soda to silica and lime to alumina ratio can be useful to distinguish between Levantine productions from different workshops and chronologies. In this instance, the Faro samples appear to align better with the Jalame glass, dated to the 4th century. Data for Levantine 1, Jalame workshop, from Brill (1999); data for levantine 1, Apollonia workshop, from Freestone et al., 2000; 2008). ^

Owing to the very small number of samples analysed for this work the conclusions that can be reached from this evidence are very limited. Despite this, recent progress in the archaeometric study of Late Roman glass has led to the expectation that we can establish patterns of supply during this period by plotting glass compositions in time and space. However, as recently argued by Govantes-Edwards et al. (2025), this is impossible to do without taking into account the full archaeological context in detail, especially ceramics, and not only for dating purposes. The Faro assemblage offered the opportunity to do just that. Even if the assemblage is, by itself, too small to reach conclusions, it is hoped that it will, modestly but positively, contribute to a more comprehensive assessment of the role of glass in Late Roman and Late Antique trade and, ultimately, once this is better understood, to begin drawing patterns of supply (if there are any, which is in no way a given). All that can be said in this instance is that the glassworkers from Faro were working with imported Levantine glass, which was found in association with other Mediterranean goods, including amphorae (Keay 25), fine wares (Ha. 59, Ha. 61, Ha. 67, Ha. 73, Ha. 91, EM. 14) and cooking wares (Ha. 23, Ha. 196, Ha. 197) from the north of Africa, along as fewer eastern amphorae and fines ware. These vessels proof the noteworthy contacts between the eastern Mediterranean and the south of the Lusitania existed, with ceramics, cloths, animals, people, and glass circulating. Whether they were using ‘raw’ glass or glass cullet is uncertain. It is also possible that they mixed this Levantine glass with other types, although this is also uncertain, because they may well have been working with glass cullet that had already undergone recycling before it reached them.

5. Conclusions ^

The construction of small glass workshops in reused existing structures appears to have been a common phenomenon during Late Antiquity. However, this is the first time that a glass workshop is identified in southern Lusitania. The glass furnace was installed in the courtyard of a former fish-salting factory, adapting part of the existing building to its new function, reusing available materials, and repurposing the space for a new role. The find presents valuable insight into the final phases of the fish-salting industry in the Algarve and the reuse of its production features, particularly in Ossonoba during Late Antiquity.

The workshop appears to have been active in the first half of the 5th century, closing down, for unknown reasons, at some point in the mid-century. However, the presence of glass-working waste in later stratigraphic contexts leaves open the possibility of subsequent glass working activity, although this is more likely the result of their deposition in secondary contexts owing to post-depositional processes.

Based on the glass shapes recovered and the results of the chemical analyses, the glass workshop in Faro was fully integrated in the late Roman ‘glass economy’, which by the 5th century was characterised by the production of largely utilitarian and fairly standardised shapes, using glass primarily melted in the Eastern Mediterranean (Egypt or the Levant), in the shape of either raw glass or cullet.

Like similar small workshops found elsewhere in the Iberian Peninsula, it is likely that the furnace in Faro worked to meet local demand, and that its productions went no farther than the city of Ossonoba and its hinterland.

The end of glass production in Faro does not appear to mark the complete abandonment of the building. Its abandonment layers reveal occupation levels with imported materials dating to the late 5th and first half of the 6th centuries. The lack of architectural features associated with these later layers limits our ability to interpret the new function of this space, located in the riverfront area of Ossonoba. However, all the evidence suggests that, by that time, it had lost its original industrial role in fish-salting and glass production.

Funding ^

This research was undertaken as part of the post-doctoral grant program JDC2023-052110-I, funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and FSE+, and is part of the activities carried out by the HUM296 “Arqueología de la Época Clásica y Antigüedad Tardía en Andaucía Oriental” research group at the Universidad de Granada. This work was also undertaken as part of the research developed under the Ramón y Cajal Research Fellowship held by Adolfo Fernández. The analytical work was undertaken with the support of the Corning Museum of Glass through a Rakow Grant awarded to David Govantes-Edwards in 2018.

Authors’ contributions ^

- Conception and design: JAR, DGE, RC, AFF, AARN

- Data analysis and interpretation: JAR, DGE, AFF, AARN

- Paper writing: JAR, DGE, RC, AFF, AARN

- Paper critical review: JAR, DGE, RC, AFF

- Data set: DGE, PB, RC, FS

- Paper final approval: JAR, DGE, RC, AFF

- Statistics support: DGE

- Fundraising: JAR, DGE

- Administrative, technical, and logistic support: PB, RC, FS

- English translation: DGE

References ^

Alarcão, J., Delgado, M., Mayet, F., Moutinho-Alarcão, A. and Ponte, S. da (1976) Fouilles de Conimbriga VI. Céramiques diverses et Verres. Paris: E. de Boccard.

Almeida, R.R. de., Fabião, C. and Viegas, C. (2017) “As ánforas de tipo la Orden na Lusitânia Meridional. Primeira leitura, importância e significado”, in Morais Arnaud, J. and Martins, A. (coords.) Arqueologia en Portugal: 2017 - Estado da Questao. Lisboa: Associaçao dos Arqueólogos Portugueses, pp. 1317-1329.

Barbosa, L.M. (2021) A cerâmica utilitária dos níveis de abandono de uma oficina de salga em Ossonoba (Faro). MA Dissertation. Coimbra: University of Coimbra. (Available at https://estudogeral.uc.pt/handle/10316/96555, accessed on May 2025)

Bernardes, J.P. (2011) “A cidade de Ossonoba e o seu território”, Anais do Municipio de Faro, 37, pp. 11-26.

Bernardes, J.P. (2014) “Ossonoba e o seu território: as transformações de uma cidade portuária do sul da Lusitânia”, in Vaquerizo, D., Garriguet, J.A. and León A. (eds.) Ciudad y territorio: transformaciones materiales e ideológicas entre la época clásica y el Altomedioevo. Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa, 20. Córdoba: Editorial Universidad de Córdoba, pp. 355-366.

Bernardes, J.P. (2022) “Um centro oleiro com registo arqueológico completa da cadeia operatória: a estação arqueológica do Marinhal (Algarve)”, in Quaresma, J.C. (ed.) Officina Hispana, Cuadernos de la SECAH 5: Cerámica en Hispania (siglos II a VII d.C.) Contextos estratigráficos entre el Atlántico y el Mediterráneo. Madrid: La Ergástula Ediciones, pp. 109-126.

Bonifay, M. (2004) Études sur la céramique romaine tardive d›Afrique. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Brems, D., Ganio, M. and Degryse, P. (2014) “Trace elements in sand raw materials”, in Degryse, P. (ed) Glass Making in the Greco-Roman World. Results of the ARCHGLASS Project. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 51-68.

Brill, R. (1967) “Lead isotopes in ancient glass”, in Annales du 4e Congrès international d’étude historique du verre. Ravenne-Venise 1962. Lieja: Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre, pp. 255-261.

Brill, R., (1999) Chemical Analyses of Early Glasses. Volumes 1 and 2. Corning: The Corning Museum of Glass.

Campos Carrasco, J.M., Vidal Teruel, N. de la O. and Gómez Rodríguez, Á. (2014) La cetaria de “El Cerro del Trigo” (Doñana, Almonte, Huelva). Huelva: Universidad de Huelva Publicaciones.

Castaño, J.M., Nieto, B., Padial, J., Peña, L. and Ruiz, S. (2009) “La ciudad romana de Acinipo”, Cuadernos de Arqueología de Ronda, 3, pp. 39-72.

Da Cruz, M. and Sánchez de Prado, M.D. (2015) “Glass working sites in Hispania: what we know”, in Lazar, I. (ed.) Annales du 19e Congrès de l’Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre. Piran 2012. Koper: Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre, pp. 178-187.

Duckworth, C. (2020) “Seeking the invisible: new approaches to Roman glass recycling”, in Duckworth, C. and Wilson, A. (eds.) Recycling and Reuse in the Roman Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 301-356. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198860846.003.0010

Fernández Fernández, A. (2014) El comercio tardoantiguo (ss. IV –VII) en el Noroeste Peninsular a partir del registro cerámico de la Ría de Vigo. Roman and Late Antique Mediterranean Pottery 5. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Fernández Fernández A., Silva, R.C., Botelho, P. and Santos, F. (in press) “Vajillas finas importadas tardoantiguas de los niveles de abandono de la factoría de salazones de la calle Francisco Barreto en Faro (Portugal)”, in VV. AA. (coords.) LRCW7. València, Riba-roja de Túria and Alacant 2019.

Fernández Fernández, A., Silva, R.C., Rodríguez Nóvoa, A., Botelho, P. and Santos, F. (2023) “Una sartén de origen egeo (Phocean Frying Pan) aparecida en un contexto cerrado del yacimiento salazonero romano de la c/ Francisco Barreto (Faro, Portugal)”, Boletín Ex Officina Hispana - SECAH, 14, pp. 62-64.

Fernández Fernández, A., Silva, R.C., Rodríguez Nóvoa, A., Botelho, P. and Santos, F. (2024) “Una olla oriental del ̒Workshop X’ aparecida en el yacimiento salazonero romano de la c/ Francisco Barreto (Faro, Portugal)”, Boletín Ex Officina Hispana - SECAH, 15, SECAH, pp. 82-85.

Fernández Rodríguez, L.-E., Peral Bejarano, C. and Corrales Aguilar, M. (2003) “Avance a los resultados obtenidos en la intervención efectuada en los jardines de IBN Gabirol, rampa de Alcazabilla. Málaga, casco histórico. 1999-2000”, Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía 2000. III-2. Sevilla: Consejería de Cultura de la Junta de Andalucía, pp. 740-750.

Feyeux, J.-Y. (1995) “La typologie de la verrerie merovingienne du nord de la France”, in Foy D. (ed.) Le verre de l’Antiquité Tardive et du Haut Moyen Âge: typologie, chronologie, diffusion. Guiry-en-Vexin: Association Française pour l’Archéologie du Verre, pp. 109-138.

Foy, D. (1995) “Le verre de la fin du IVe au VIIIe siècle en France méditerranéenne, premier essai de typo-chronologie”, in Foy, D. (coord.) Le verre de l’Antiquité tardive et du Haut Moyen Âge: typologie, chronologie, diffusion. Guiry-en-Vexin: Association Française pour l’Archéologie du Verre, pp. 187-242.

Foy, D., Picon, M., Vichy. M. and Thirion-Merle, V. (2003) “Caractérisation des verres de l’Antiquité tardive en Méditerranée occidentale: l’émergence de nouveaux courants commerciaux”, in Foy, D. and Nenna, M.-D. (eds.) Échanges et commerce du verre dans le monde antique. Actes du colloque de l’AFAV. Aix-en-Provence - Marseille 2001. Montagnac: Monique Mergoil, pp. 41-86.

Freestone, I. (2006) “Glass Production in Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic Period: a Geochemical Perspective”, Geological Society Special Publications, 257, pp. 201-216. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.2006.257.01.16.

Freestone, I. (2015) “The Recycling and Reuse of Roman Glass: Analytical Approaches”, Journal of Glass Studies, 57, pp. 29-40.

Freestone, I., Gorin-Rosen, Y. and Hughes, M.J. (2000) “Primary glass from Israel and the production of glass in Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic Period”, in Nenna, M-D. (ed.) La route du verre: ateliers primaires et secondaries du second millénaire av. J-C. au Moyen Âge. Lyon: Maison de L’Orient Méditerranéen, pp. 65-83.

Freestone, I., Jackson-Tal, R.E. and Tal, O. (2008) “Raw Glass and the Production of Glass Vessels at Late Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf, Israel”, Journal of Glass Studies, 50, pp. 67-80.

Freestone, I., Wolf, S. and Thirwall, M. (2009) “Isotopic composition of glass from the Levant in the south-eastern Mediterranean Region”, in Degryse, P., Henderson, J. and Hodgins, G. (eds.) Isotopes in Vitreous Materials. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 31-52 https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qdx40.6

Freestone, I., Degryse, P., Lankton, J., Gratuze, B. and Schneider, J. (2018) “HIMT, glass composition and commodity branding in the primary glass industry”, in Rosenow, D., Meek, A., Phelps, M. and Freestone I. (eds.) Things that Travelled: Mediterranean Glass in the First Millennium AD. London: UCL Press, pp. 159-190.

Fünfschilling, S., (2015) Die römischen Gläser aus Augst und Kaiseraugst. Kommentierter Formenkatalog und ausgewählte Neufunde 1981–2010 aus Augusta Raurica. Augst: Augusta Raurica, pp. 466-531.

García-Aboal, V., Govantes-Edwards, D., Duckworth, C. and Noguera, J.M. (2023) “El taller vidriero de los siglos IV-V de la Insula II del Molinete (Cartagena, España): análisis arqueológico e interpretación”, Spal, 32, pp. 250-290.

Govantes-Edwards, D. (2025) “Pottery and glass”, in Gearhart, H. (ed.) A Cultural History of Craft in the Medieval Age. London: Bloomsbury Academic Publishing, pp. 107-123.

Govantes-Edwards, D., Férnandez Fernández, A., and Duckworth, C. (2025). “The Atlantic road: late antique/early medieval glass trade in Iberian northwest”, Medieval Archaeology, 69 (1), pp. 1-34.

Govantes-Edwards, D., Velo, A., Hernández-Robles, A., González-Ballesteros, J. A, and Duckworth, C. (2024) “The glass from the arrabal of Arrixaca (Murcia, 12th-13th centuries)”, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 16, e167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-024-02066-6

Harden, D.B. and Price, J. (1971) “The Glass”, in Cunliffe, B. (ed.) Excavations in Fishbourne, 1961-1969. Volume II: the finds. London: The Society of Antiquaries, pp. 317-370.

Hayes, J. (1972) Late Roman Pottery. London: The British School at Rome.

Hiraldo Aguilar, R., Martín Ruíz, J.M. and Sánchez Bandera, P.J. (2004) “Informe preliminar de la excavación arqueológica de urgencia en la ciudad romana de Suel (Fuengirola, Málaga)”, Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía 2001. III-2. Sevilla: Consejería de Cultura de la Junta de Andalucía, pp. 729-736.

Isings, I. (1957) Roman glass from dated finds. Groningen/Djakarta: Academiae Rheno/Traiectina Instituto Archaeologico.

Lazar, I. (2006) “An oil lamp from Slovenia depicting a Roman glass furnace”, Vjesnik za arheologiju I povijest dalmatinsku, 99, pp. 227-234.

Leonne, A. (2003) “Topographies of production in North African cities during the Vandal and Byzantine periods”, in Lavan L. and Bowden, W. (eds.) Theory and Practice in Late Antique Archaeology. Boston: Brill, pp. 257-287.

Lilyquist, C. and Brill, R.H. (1993) Studies in Early Egyptian Glass. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mantas, V. (2016) “Navegação e Portos no Algarve Romano”, Al–Úlyá: Revista do Arquivo Municipal de Loulé, 16, pp. 25-51.

NIST (1992) Certificate of Analysis. Standard Reference Material 612. Trace Elements in Glass.

Paynter, S. and Jackson, C. (2016) “Re-used Roman rubbish: a thousand years of recycling glass”, European Journal of Postclassical Studies, 6, pp. 31-52.

Pineda de las Infantas Beato, G. (2002) “Intervención arqueológica de urgencia en la factoría de salazones de C/ Cerrojo 24-26 (Málaga)”, Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía 1999. III-2. Sevilla: Consejería de Cultura de la Junta de Andalucía, pp. 479-189.

Rehren, Th. and Brüggler, M. (2015) “Composition and production of late antique glass bowls type Helle”, Journal of Archaeological Science Reports, 3, pp. 171-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.05.021

Rehren, Th. and Freestone, I. (2015) “Ancient glass: from kaleidoscope to crystal ball”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 56, pp. 233-241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2015.02.021

Rehren, Th. and Rosenow, D. (2020) “Three millennia of Egyptian glassmaking”, in Duckworth, C., Cuenod, A. and Mattingly, D. (eds.) Mobile technologies in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp- 423-450.

Retamosa, J.A. 2022. El vidrio romano en contextos pesqueros-conserveros del sur de Hispania. Análisis a través de los casos de Baelo Claudia (Ensenada de Bolonia, Tarifa) e Iulia Traducta (Algeciras). PhD Dissertation, Cádiz: Universidad de Cádiz. (Available at http://hdl.handle.net/10498/28829, accessed on May 2025).

Retamosa, J.A. and Expósito, J.Á. (2024) “El vidrio romano en las cetariae de Carteia: estudio de los casos de La Madre Vieja y del denominado «Jardín Romántico»”, in Expósito, J.Á. and Bernal-Casasola, D. (eds.) Carteia y el ciclo haliéutico. Reflexiones y novedades en el marco del Fretum Gaditanum. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, pp. 131-144.

Retamosa, J.A., Díaz, J.J., Bernal-Casasola, D. and Oviedo, J. (2020) “El vidrio en las fábricas pesquero-conserveras romanas, una nueva línea de investigación”, in Bernal-Casasola, D., Díaz, J.J., Expósito, J.Á. and Palacios, V. (eds.) Baelo Claudia y los secretos del garum. Cádiz: Editorial UCA, pp. 208-221.

Rodríguez Nóvoa, A., Silva, R.C., Fernández Fernández, A., Botelho, P. and Santos, F. (2024) “Materiales cerámicos del abandono de un pozo romano en la fábrica de salazones de la c/ Francisco Barreto (Faro, Portugal)”, Promontoria digital, 1, pp. 395-409.

Rodríguez Nóvoa, A., Fernández, A., Silva, R.C., Botelho, P. and Santos, F. (in press) “Cerámica fina alto imperial de la fábrica de salazón de la calle Francisco Barreto en Ossonoba (Faro, Portugal)”, Humanitas, 85.

Rosenow, D. and Rehren Th. (2014) “Herding cats – Roman to late Antique glass groups from Bubastis”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 49, pp. 170-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2014.04.025.

Sánchez de Prado, M.D. (2014) “La producción de vidrio en Valentia. El taller de la Calle Sabaters”, Lucentum, 33, pp. 215-242.

Sánchez de Prado, M.D. (2018) La vajilla de vidrio en el ámbito suroriental de la Hispania romana. Comercio y producción entre los siglos I-VII d.C. Alicante: Publicacions Universitat d’Alacant.

Shortland, A., Schachner, L., Freestone, I. and Tite, M. (2006) “Natron as flux in the early vitreous materials industry: sources, beginnings and reasons for decline”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 33, pp. 521-530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2005.09.011

Silva, R. C., Fernández, A., Botelho, P. and Santos, F. (in press) “Un contexto anfórico cerrado proveniente de una fosa associada a la factoría de salazón de la C. Francisco Barreto (Faro, Portugal)”, in Bernal Casasola, D., García Vargas, E., González Cesteros, H. and Mauné, S. (coords.) EX BAETICA AMPHORAE II Actas. Conservas, azeite e vinho da Bética no Império Romano. Vinte anos depois. Sevilla, 2018.

Viegas, C. (2011) A ocupação romana do Algarve. Estudo do povoamento e economia do Algarve central e oriental no período romano. Estudos e Memórias 3. Lisboa: UNIARQ.