Rural livelihoods, poverty and social protection in a former Soviet country, Kyrgyzstan[*]

Medios de vida rurales, pobreza y protección social en un antiguo país soviético, Kirguistán

Rafael Aguirre Unceta

Investigador independiente

Excoordinador de cooperación UE en Asia Central

agisor@gmail.com  0000-0002-3417-4776

0000-0002-3417-4776

e-Revista Internacional de la Protección Social ▶ 2024

Vol. IX ▶ Nº 1 ▶ pp. 132-151

ISSN 2445-3269 ▶ https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/e-RIPS.2024.i01.06

Recibido: 30.03.2024 Aceptado: 04.06.2024

|

RESUMEN |

PALABRAS CLAVE |

|

|

In Kyrgyzstan, many rural families have tried to escape poverty by migrating to urban centres within the country or abroad. Although the poverty rate has tended to decline over the course of this century, it has recently increased significantly, mainly due to the COVID pandemic and its aftermath. A few years after independence from the USSR (1991), the national government reintroduced a model of social protection, albeit less generous than that of the Soviet era. With some partial reforms, this model has been maintained until today. Its effectiveness seems insufficient, especially the non-contributory component, which supports poor rural and urban families. The situation of the latter is aggravated by the limited scope and coverage of free public health services. Despite tight national budget margins, fiscal space could be created to refinance some national priorities. These include the social protection system. However, this system should also be redesigned to become more progressive and poverty-oriented. |

Rural Livelihoods Migration Poverty Trends Financing Social Policies Anti-Poverty Programmes |

|

|

ABSTRACT |

KEYWORDS |

|

|

En Kirguistán, muchas familias rurales han intentado escapar de la pobreza emigrando hacia núcleos urbanos dentro del país o al extranjero. Aunque ha tendido a disminuir a lo largo del presente siglo, la tasa de pobreza ha experimentado recientemente un aumento significativo, principalmente a causa de la pandemia COVID y sus consecuencias. Pocos años después de la independencia de la URSS (1991), el gobierno nacional reintrodujo un modelo de protección social, aunque menos generoso que el de la época soviética. Con algunas reformas parciales, este modelo se ha mantenido hasta la fecha. Su eficacia parece insuficiente, en particular su componente no contributivo que apoya a las familias pobres rurales y urbanas. Estas últimas ven agravada su situación por el limitado alcance y cobertura de los servicios sanitarios públicos gratuitos. A pesar de los estrechos márgenes del presupuesto nacional, podría crearse espacio fiscal para refinanciar algunas prioridades nacionales. Entre ellas, estaría el sistema de protección social. No obstante, este sistema debería también rediseñarse para hacerse más progresivo y orientado a la reducción de la pobreza. |

Medios de vida rurales Migración Tendencias de pobreza Financiación de políticas sociales Programas antipobreza |

CONTENTS

II. FARM AND NONFARM LIVELIHOODS, MIGRANT REMITTANCES

A. Agriculture and non-agricultural activities

C. Foreign migration and remittances

IV. AN INSUFFICIENT SOCIAL PROTECTION SYSTEM

A. System development and configuration

B. Scope and challenges of the current antipoverty policy

I. INTRODUCTION ^

After belonging to the Russian Empire in the last quarter of the 19th century and to the USSR in the 1920s, Kyrgyzstan became an independent republic in 1991. As in the other ex-USSR countries of Central Asia, the transition from a planned to a market economy has been difficult. The disruption of production and trade patterns under the USSR’s internal division of labour led to the closure of many production facilities and high rates of inflation. Public finances suffered from the loss of transfers from the Union and the difficulty of mobilizing domestic revenues in the context of transition[1]. After several years of sharp economic decline, GDP began to recover at the end of the 1990s and has been growing moderately (3.8 percent per year on average) since the turn of the century[2]. The government’s fiscal position has gradually improved from the previous high level of indebtedness (122.3 percent of GDP in 2000). However, the Kyrgyz economy remains vulnerable to external shocks due to its dependence on gold markets (about 40 percent of total exports) and migrant remittances (29.9 percent of GDP between 2015 and 2022).

The economic turmoil that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union led to major social problems. Escalating unemployment, cuts in social subsidies, and rising living costs led to increased poverty and food insecurity for large sections of the population. Poverty rates have fallen in the last decades, with some recent reversals (2009-12, 2015); the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences (job losses, high inflation, etc.) have caused a further significant increase in the poverty rate. Although it has recently grown in cities, poverty has traditionally been concentrated in rural areas, linked to fragile agricultural production. The gap between the value added by agriculture (14.7 percent of GDP in 2021, WDI/World Development Indicators) and its share in national employment (25.2 percent in 2021, ILOSTAT) reflects its low productivity. To escape poverty, rural people seek employment outside agriculture, in the same area, in other parts of the country or abroad. The drivers and conditions of this search for livelihood, as well as broader poverty trends in Kyrgyzstan, are considered in sections II and III of this article.

To address the social vulnerability of many of its citizens, independent Kyrgyzstan has implemented a social protection model partly inspired by the Soviet legacy. Its main component is a pension system, which covers a large proportion of the elderly population and absorbs most of the social protection budget. The non-contributory social assistance component consists of both categorical and poverty-targeted grants; their limited funding means that only a small part of the population is reached with a low level of benefit. National budget allocations for social policies have evolved over the course of this century (section IV). Neither social protection nor public health care appear to be favoured when compared to countries with relatively similar conditions. There seem to be some fiscal possibilities to remedy this situation. Section V examines in more detail some of the imbalances and shortcomings within the social protection system that reduce its effectiveness in the fight against poverty. Part of the statistical information used in the article comes from databases of international institutions, such as the World Bank (WDI/World Development Indicators), the Asian Development Bank, the International Labour Organization (ILOSTAT), the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS-UNESCO) or the World Health Organization (WHO). The other main source of data is the National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (NSCK).

II. FARM AND NONFARM LIVELIHOODS, MIGRANT REMITTANCES ^

Kyrgyzstan remains a demographically rural country. In 2022, 63 percent of the population lived in rural areas, slightly lower than in 1960 (66 percent) (WDI/World Development Indicators), after some urban industrialization during the Soviet period. While agriculture has historically been the main source of activity and income in these areas, there has been a trend to seek employment in non-agricultural rural activities. Throughout this century, another alternative to escape rural hardship and unemployment has been migration, usually temporary, to urban centres or other countries.

A. Agriculture and non-agricultural activities ^

Current farm ownership structures in Kyrgyzstan are the result of the privatization of land and livestock that took place after independence. After more than 60 years of collectivization, agrarian reform began in 1991, although it did not become fully effective until 1995[3]. Arable land and livestock from state and collective entities were officially redistributed to their former members on an equal per capita basis. However, actual individual shares varied according to the available assets of each dissolved entity and the number of eligible members. In addition, lack of administrative control, local nepotism and corruption led to frequent violations of the legal rules in favour of some powerful people[4].

A quarter of the total arable land was not legally redistributed because it was used to set up a Land Redistribution Fund (LRF) for public agronomic research, for subsequent lease or allocation to dispossessed peasants, etc. Pastures (approximately 85 percent of the total agricultural land) also remained in public hands. In both cases, the management of public assets was confused, leading to arbitrary decisions and semilegal allocations (pastures)[5]. In some areas, the legal portion of the LRF had previously been distributed individually at the local level. Since the beginning of this century, more precise norms for LRF and pasture leasing have been adopted (2009), although conflicts over access to pastures persisted[6]. During the same period, the legal possibility of land sales by private owners was introduced, and an increasing number of such transactions took place[7].

In addition to the above developments, demographic factors and the weight of traditional family rules (especially for women) have led to inequalities in land ownership. In 2012, 57.5 percent of women and 43.4 percent of men living in rural areas and aged between 15 and 49 years did not own any land [8]. Moreover, the fragmentation of farms (inheritance, etc.) has reduced their size. In just one decade (2006-2016), the number of smallholder farms increased by 30 percent (AO/Food and Agriculture Organization, 2020). This, together with the redistribution criteria of the 1990s reform (arable land available/population in each place), means that farm sizes are particularly modest in some regions. In the southern oblasts (Batken, Jalalabad and Osh), the average farm size is between 0.6 and 1.1 hectares), including the tiny portions of land leased from the LRF. The national average household livestock is not large: 2-3 livestock units (LU) (mostly one cow and 10-20 small ruminants). The poorest families have no livestock or very few ruminants or poultry.

The small size of farms can be aggravated by obsolete technical means of production and poor-quality inputs (seeds, fertilizers, etc.), resulting in low yields. The agricultural cooperative movement could alleviate these production constraints, but it is very weak in Kyrgyzstan. Despite official promotional campaigns, insufficient mutual trust among farmers hinders their cooperative organization. Climate-related risks (such as drought, harsh winters for pastoralists, earthquakes, and landslides) are also significant[9]. Selling part of the agricultural products can also pose other difficulties (roads, bridges...), especially in mountainous areas far from markets; the returns obtained are generally low. A significant proportion of smallholders practise subsistence farming to meet their needs, with no surplus to sell. The poorest household farmers, who often have only a home garden, are unable to produce their basic food, become dependent on the market and suffer from price rises.

B. Internal migration ^

To cope with inadequate food and income from agriculture, members of peasant families often must find employment outside the farm. This may be wage jobs as herders or labourers on other farms or employment in services or processing activities related to agriculture. However, non-agricultural employment is also common. Sometimes this takes the form of part-time or seasonal work, which to some extent smooths income at home but also migration to more permanent destinations. These may be nearby, further afield within the country or abroad. The most significant internal migration movements are between poor rural areas in the south (Batken, Jalalabad) and northern destinations such as the capital Bishkek and its region (Chui oblast).

Nonfarm employment (or self-employment) in the country is provided by sectors such as trade, transport, construction, and textiles, as well as local public services. Poor rural households try to increase their earnings through nonfarm employment, mainly in trade and construction. However, the income generated is not sufficient to change their poverty status. In their destination areas, migrants typically endure poor working conditions and low wages. Their access to urban health and social services is also hampered by the migrant registration system, known as propiska, inherited from the Soviet era[10].

C. Foreign migration and remittances ^

International migration flows are mainly to the Russian Federation[11] and, to a lesser extent, to Kazakhstan, Turkey, and some other countries. Kyrgyz migrants abroad come from both rural and urban areas, from both northern and southern oblasts; in fact, a common sequence is to first migrate to urban centres and from there to migrate abroad. It should be noted that migration may require financial resources that are not available to the poorest rural families. The main reasons for labour migration are low wages[12] and unemployment in Kyrgyzstan, although working and living conditions in Russia are not great. It has been observed that migrants in Russia are largely discriminated against in terms of wages, as they are quite often employed in the shadow economy[13].

In a small open economy such as Kyrgyzstan’s, migrant remittances tend to have a significant macroeconomic weight, although they are quite volatile. Exchange rate fluctuations and changing economic conditions in Russia explain this instability. As a share of GDP, remittances have fluctuated between 25.3 percent (2015) and 32.8 percent (2021) over the last decade, levels that are among the highest in the world [14]. Due to their important role in providing foreign exchange, remittances contribute to financing critical imports, thereby supporting the external balance. Let´s now look at the microeconomic impact of foreign remittances on recipient families.

According to data from the very comprehensive Life in Kyrgyzstan study, 10.4 percent of Kyrgyz households received remittances in 2016, of which 74.3 percent lived in the rural home areas of migrants. The three southern oblasts have the highest proportion of recipient families (16.4 percent). Of the total income of these recipient families, 75.1 percent came from remittances in 2016. At the national level, remittances accounted for only 7.9 percent of total household income (recipient and nonrecipient families) in the same year.

The impact of remittances on poverty in Kyrgyzstan has been the subject of several studies, with relatively mixed results. Some conclude that the impact is positive because they allow households to increase their spending capacity[15]. Similarly, a World Bank report[16] finds that remittances increase the probability of moving out of poverty. The impact of remittances on crops, livestock and off-farm activities has led to the conclusion that remittances have an overall positive impact on rural poverty reduction[17]. Other research tends to deny such a positive impact, at least for the poorest households. Permanent migration may even increase the vulnerability of these households through the loss of active, productive members[18]. Remittances can reproduce social stratification in rural communities, as the poorest use them for immediate consumption needs, while the wealthier can invest them productively.

The official poverty statistics capture the transient effect of remittances on household income and expenditure levels and show a reduction in poverty rates. According to the National Statistical Committee, remittances contributed to reducing the national poverty rate by 9.3 percentage points in 2020. The question that arises, and perhaps explains the different conclusions outlined above, is whether remittances lead to sustainable improvement in household incomes and conditions. It has often been assumed that poor households use remittances mainly for immediate consumption needs, including food[19], without strengthening the resilience of their livelihoods. This leaves them poorly prepared to cope with possible shocks (climatic or otherwise) or a sudden drop in remittances[20]. Moreover, not only productive investment but also spending on human capital, especially education, appears to be relatively neglected, which may affect household well-being in the long run[21].

III. POVERTY AND INEQUALITY ^

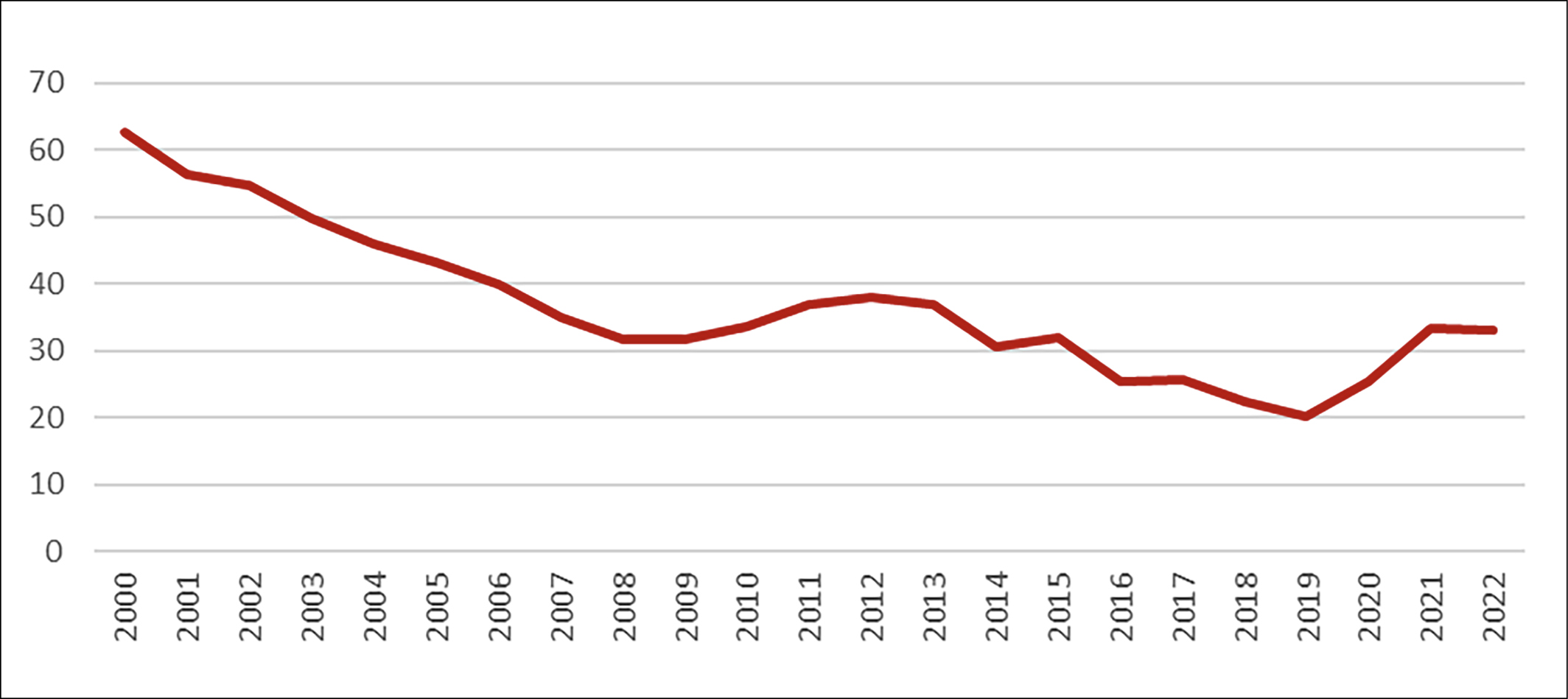

With fluctuations linked to economic cycles and crises, poverty rates have tended to decline gradually since the beginning of this century (figure 1). The fragility of this decline has been demonstrated recently by a combination of adverse factors. These include the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic aftermath, rising unemployment in some areas and high food inflation. Between 2019 and 2021, the poverty rate (according to the national line) raised from 20.1 percent to 33.3 percent of the population, and extreme poverty from 0.5 to 6 percent. These increased poverty rates are maintained in 2022 (33.2 percent and 6.1 percent, respectively. The 2023 poverty rate has not yet been published by the NSCK. Remittances fell sharply in 2020 during the worst phase of the pandemic but have recovered since then (28 percent increase in 2022 compared to 2020).

Rural areas tend to have the highest levels of poverty: 73.7 percent of people below the national poverty line lived in these areas in 2020. However, the largest increase in poverty rates between 2020 and 2022 has occurred in urban areas. Territorial disparities become apparent when the latest poverty data are disaggregated by oblast. Poverty rates in the southern oblasts Batken (48.5 percent) and Jalalabad (47.1 percent) were well above the national average (33.2 percent) in 2022 (NSCK/National Statistical Committee data), despite being a major destination for remittances. A similar conclusion is reached if multidimensional poverty estimates are considered. As reported by a UNICEF study [22], 50,3 percent of Kyrgyz households were living in 2016 in multidimensional deprivation; the ratio was 64,9 percent in Batken and 59,6 percent in Jalalabad.

Figure 1.

Poverty rates according to the national line (% of the population)

Source: NSCK/National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic

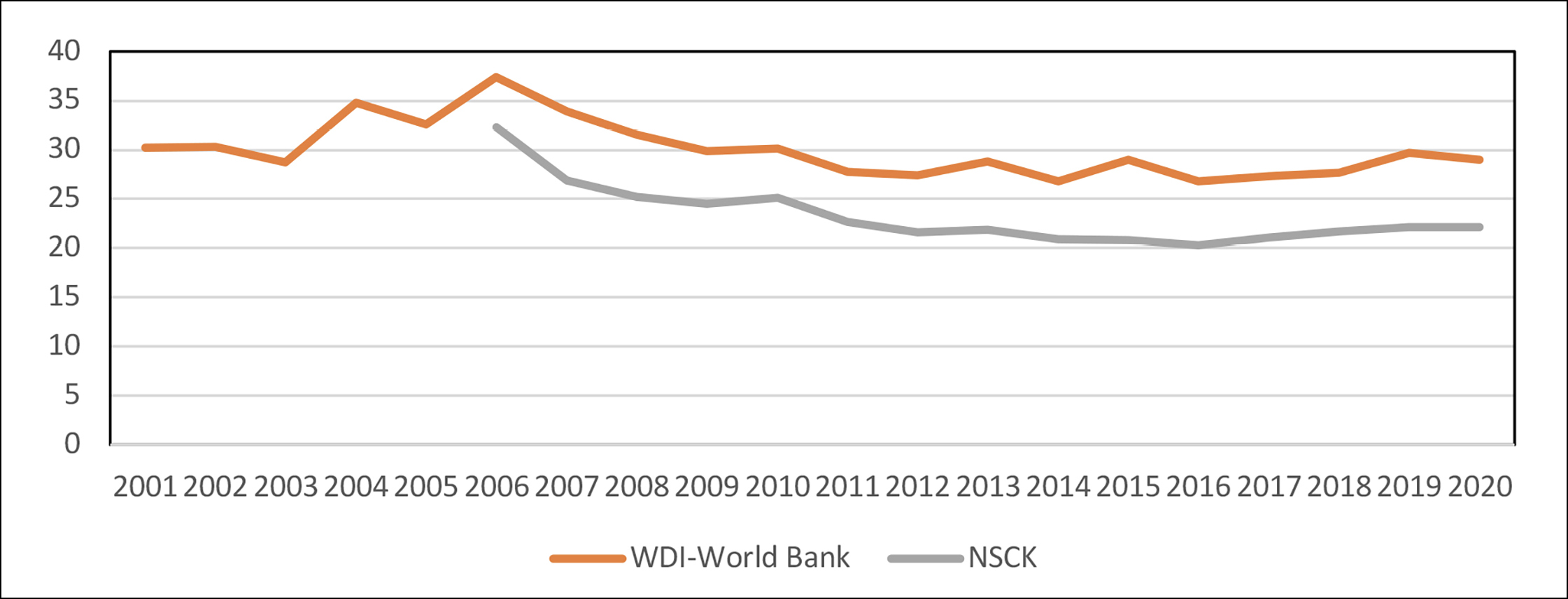

Regarding interpersonal inequality, Kyrkyzstan shows an unstable path over the last 20 years. After an initial rise, the Gini coefficient has been falling for almost a decade, but this trend has recently been reversed (figure 2). The Gini level in 2020 is quite similar to that at the beginning of the century. There are several reasons for the persistence of inequality. These include land inequality, a large informal economy with low wages and little protection, the regressive burden of inflation, institutional weakness, and instability and, perhaps most importantly, unequal access to education. On this last point, the figures from the WIDE-UNESCO (World Inequality Database on Education) speak for themselves. The difference between the richest and the poorest is evident in completion rates at secondary level (96 percent and 78 percent, respectively) and becomes very significant at tertiary level (66 percent and 12 percent). The gap between the two social groups in tertiary graduation rates is equivalent to 54 percentage points.

Figure 2.

Inequality. Gini-coefficient (0-100)

Source: WDI-World Bank and NSCK

IV. FINANCING SOCIAL POLICIES

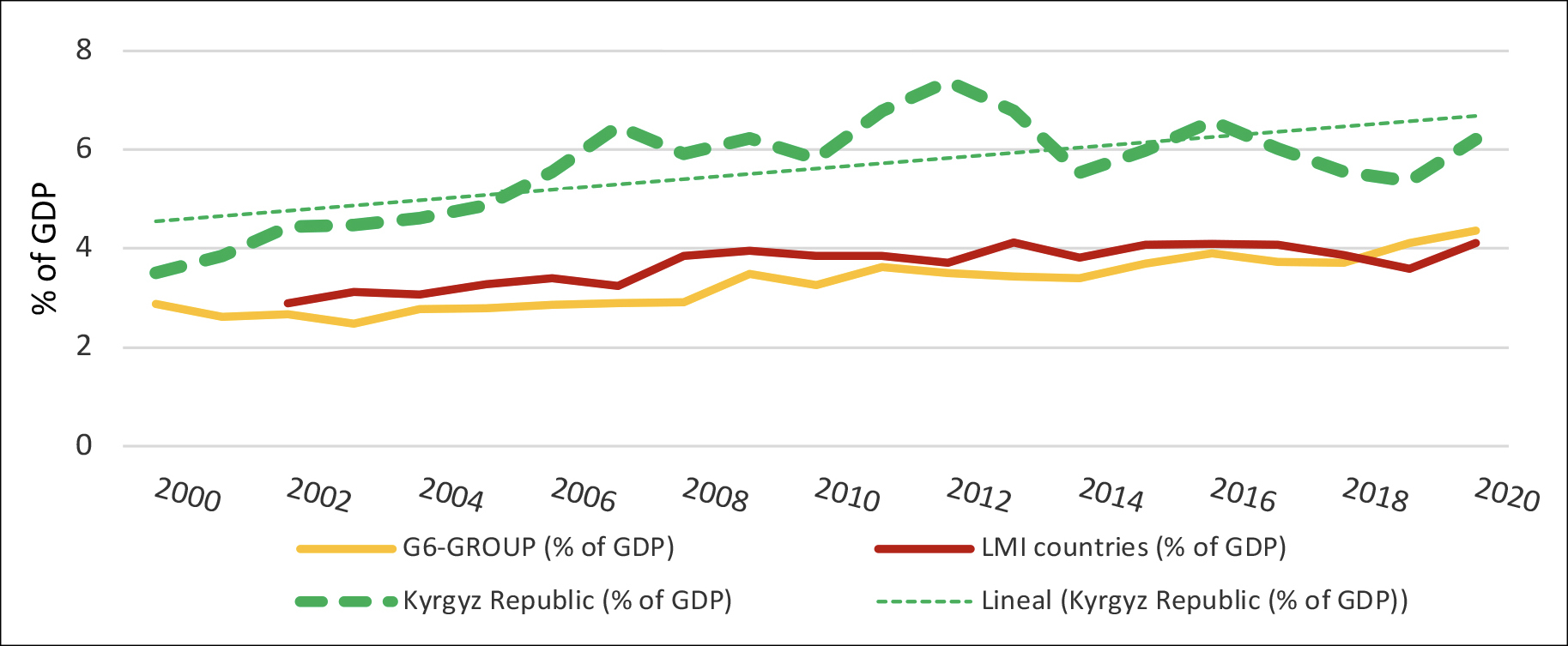

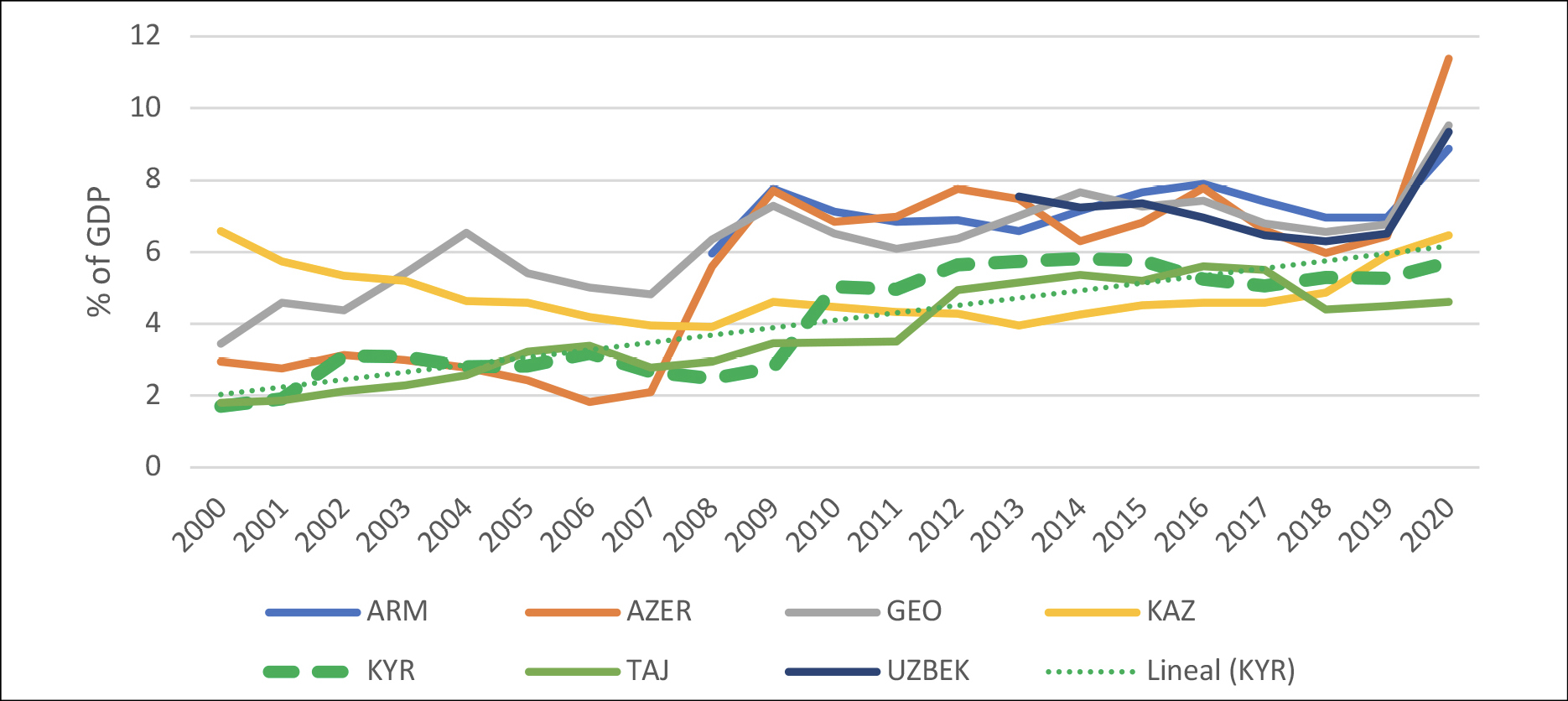

Let us first look at the evolution of budgetary expenditure in the areas (education, health and social protection) that can have the greatest impact on poverty and social development. Kyrgyzstan’s social spending, particularly on education and social protection, has shown an increasing trend over the course of this century (trend lines in Figures 3, 4, and 5). However, while this trend was strong in the first decade, it has not continued in the second[23]. There is even a regression in the health sector. Despite this, the budgetary weight of social spending has remained quite significant over the last decade. According to national statistics (NSCK data), expenditures over the period 2010-2021 in the three mentioned areas averaged 14.5 percent of GDP and accounted for 47.6 percent of total public spending. Specifically, social protection expenditures accounted for 5.4 percent of GDP and 17.8 percent of total budget spending.

It is worth observing these levels of social spending in Kyrgyzstan in relation to those of other countries in relatively comparable circumstances. To this end, consideration is given to data from UIS-UNESCO (education) and WHO (health) on:

- a group of six Caucasus-Central Asia ex-Soviet countries (hereafter referred to as the G6 group)[24].

- as well as the whole group of Lower Middle-Income countries (World Bank criteria) in which Kyrgyzstan has been ranked since 2014 (referred to as LMI).

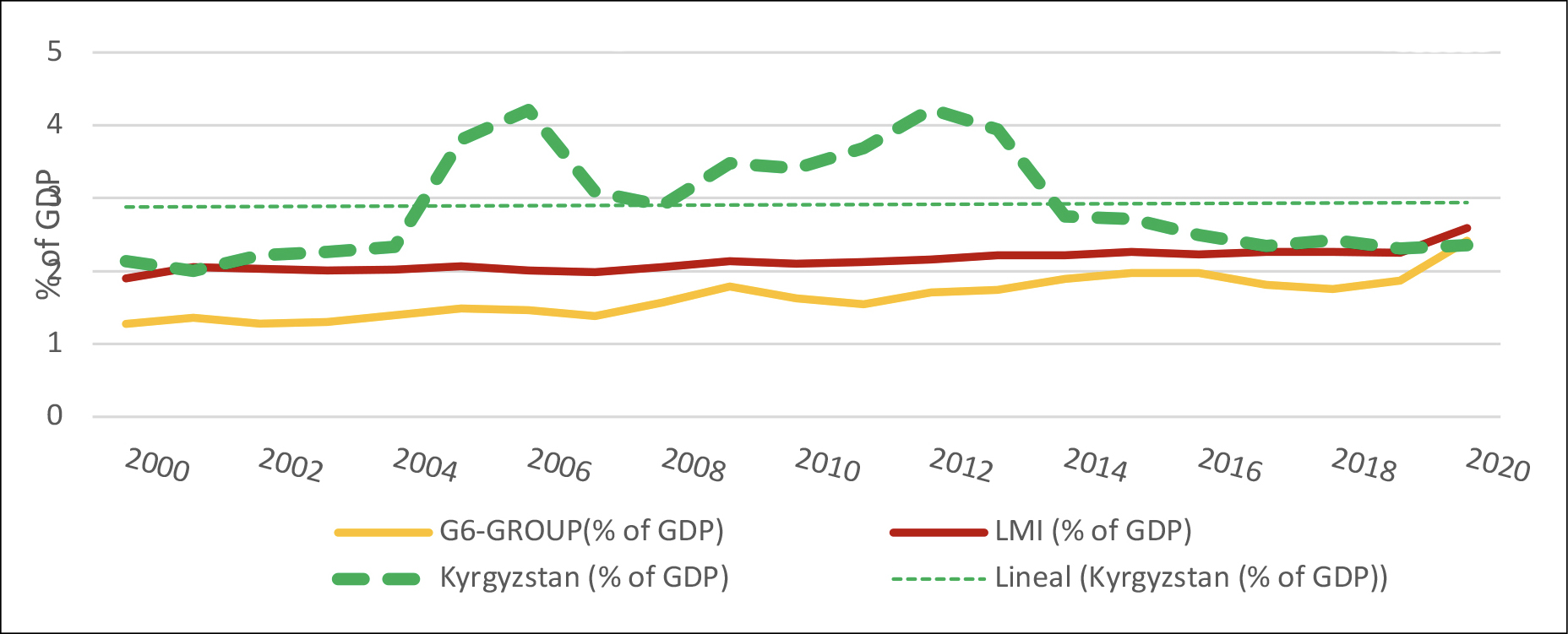

It can be seen (figure 3) that Kyrgyzstan has tended to maintain higher levels of education expenditure than both the G6 and the LMI group[25]. The picture is different when it comes to the health sector. After a period in which the ratios of health expenditure exceeded those of the G6 and LMI groups, they have levelled off in recent years (Figure 4). The downward trend in this sector is evident in terms of the share of total public budget spending: from 11,03 percent in 2006-2010 to 6,82 percent in 2016-2020 (WHO data).

Figure 3.

Public expenditure on education as a share of GDP (%)

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS-UNESCO)

Figure 4.

Public expenditure on health as a share of GDP(%)

Source: WHO data

Some additional indicators for education and health public spending (table 1) may lead to two brief comments: 1) the low comparative level of health in terms of budget allocation; 2) in absolute terms, per capita spending in health is slightly above that of the LMI countries, but much lower than in the G6 (Caucasus-Central Asia group)[26].

Table 1

Education and health spending indicators

|

Education expenditure/total budget spending (2016-20) |

Health expenditure/total budget spending (2016-20) |

Public health spending per capita (2016-20) USD PPP |

|

|

Kyrgyzstan |

17.43 |

6.82 |

123.5 |

|

LMI Countries |

15.29 |

7.74 |

105.2 |

|

Group Caucasus-Central Asia |

14.19 |

7.16 |

251.8 |

It is more difficult to select international indicators that allow a comparison of social protection expenditure. Here we turn to the Asian Development Bank’s key fiscal indicators[27] for Kyrgyzstan and the G6 countries (Figure 5), including social protection expenditure as a ratio to GDP[28]. Despite the increase in this ratio in Kyrgyzstan, particularly in the first decade of this century, it remains below that of most G6 countries.

Figure 5.

Public expenditure on social protection (% of GDP)

Source: ADB/Asian Development Bank. Key Indicators for Asia and the Pacific 2022

Public spending on social protection is largely absorbed by pensions, while funding for specific anti-poverty programmes is weak, with low coverage and impact (see section V). These programmes have proven to be uncapable of responding to shocks such as those arising from COVID and the recent high inflation. Low and declining public funding for health, as noted in recent analyses of this sector in Kyrgyzstan[29], further complicates the situation. The State Guaranteed Benefits Programme (SGBP) provides free health services, but its coverage and scope are limited, especially for inpatient care and medicines; there are marked rural-urban disparities. The importance of out-of-pocket contributions[30] and ‘informal’ payments for access to some services has a serious impact on the most vulnerable households[31].

The need for increased budget funding seems evident both in health and in the area of anti-poverty social protection. The question is whether fiscal space could be created to meet these financing needs to the extent possible. Options in this sense may exist both on the revenue side and through some expenditure reallocation, despite the country’s tight public finance position. Taxation of personal and corporate income remains weak in Kyrgyzstan[32]. The progressive and redistributive capacity of the Kyrgyz’s personal income tax is below that of many comparable countries[33]. A reform to address this has been advocated by both international institutions and local experts[34]. Another key issue would be ensuring revenue from the country’s mining resources, following the recent nationalization of the main gold mine (Kumtor). On the spending side, some budget lines carry a disproportionate comparative burden (e.g., public wages). Others, such as the energy subsidies, are not only socially regressive[35], but also reduce resources for energy infrastructure renewal[36]. Rationalizing spending in these two areas could free up resources for other critical national needs.

V. AN INSUFFICIENT SOCIAL PROTECTION SYSTEM ^

A. System development and configuration ^

The Soviet welfare system that Kyrgyzstan inherited was very broad in its distribution of benefits, with criteria based on age and work history rather than poverty. Approximately half the population received pensions or family allowances, largely funded by transfers from the Soviet Union. When these disappeared, the system became unsustainable, and the independent government had to make substantial budget cuts. Between 1991 and 1992, spending on family allowances fell from 6.7 to 2.6 percent of GDP, and spending on pensions fell from 7 to 3.6 percent of GDP[37]. Years of widespread social deprivation and rising poverty followed.

Since 1995, in a more stable fiscal context, an attempt was made to build a new social protection system while retaining some features of its Soviet predecessor. A new Pensions Act (1997) raised the retirement age and introduced, together with a basic pension component, notional pensions linked to the active life contributions of their beneficiaries. A law on state benefits was adopted in 1998. It introduced the first poverty-targeted social assistance programme, the Unified Monthly Benefit (UMB), for families with children and a (mean-tested) income below a guaranteed minimum income (GMI). The same law created the Monthly Social Benefit (MSB), payable to various vulnerable groups regardless of income (disabled people, orphans, mothers with large families, elderly people not entitled to a pension). During the same period, various laws reinstated the so-called privileges, a legacy of the Soviet period, which were also granted irrespective of income. This type of support was reserved for special categories of citizens (war veterans, concentration camp survivors, Chernobyl liquidators, people living in mountainous areas, etc.). Privileges initially consisted of discounts on public utilities, housing, health services, etc.

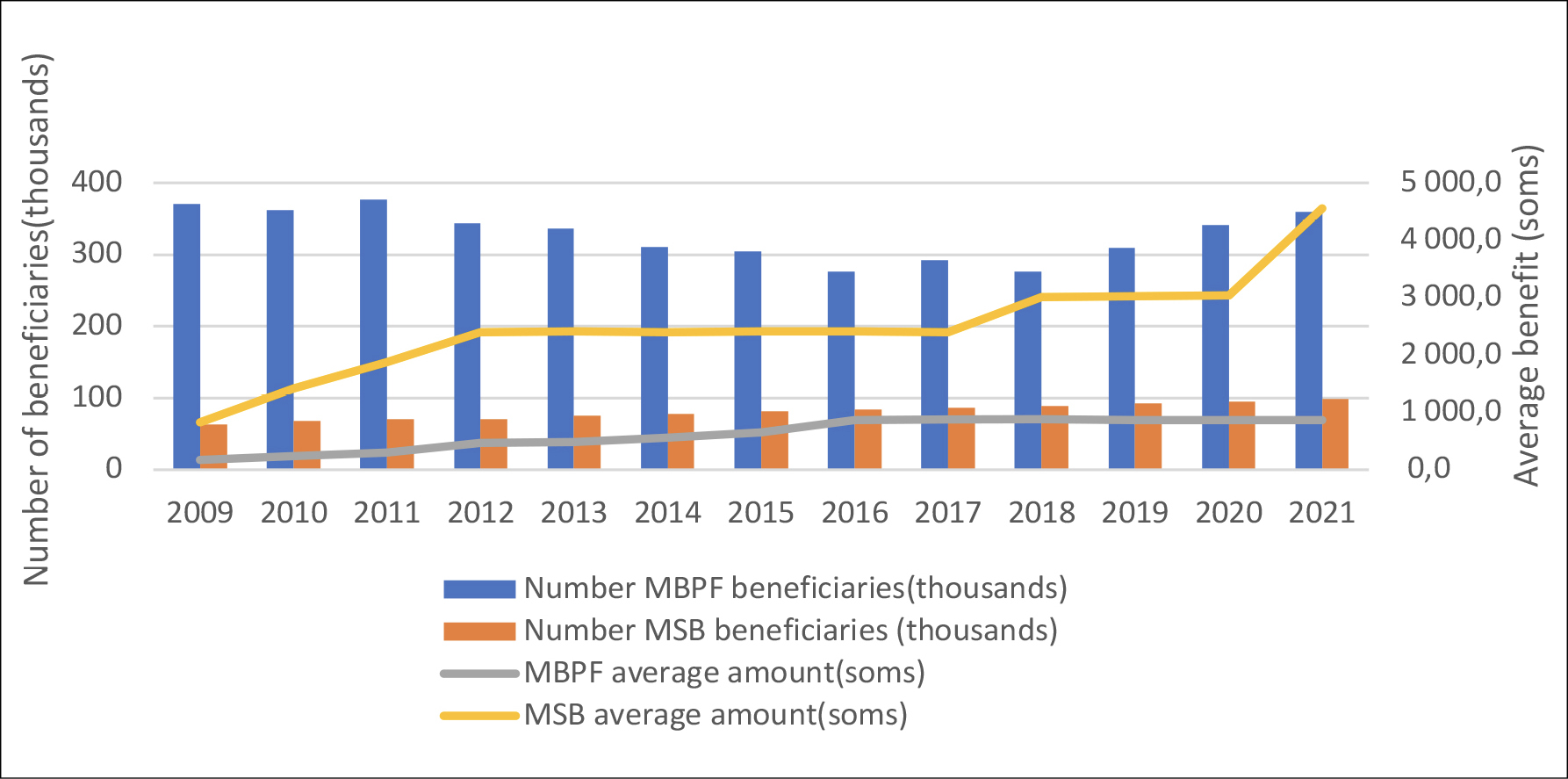

With some partial reforms, the above social protection principles have been maintained to date. The retirement age has been subject to legislative changes that have lowered or raised it (currently 63 for men/58 for women, as set in 1997). The 1998 law on state benefits was amended in 2009. In an attempt to address the low impact and coverage of the UMB, it was renamed the monthly benefit for poor families (MBPF) and focused more on extremely poor families. The 2009 law also sought to reduce the significant number of inclusion and exclusion errors found in both the previous UMB and the MSB. Since 2010, in-kind privileges have been monetised, adding to the already high cost of what is, in practice, an opaque part of the social protection system. Despite a significant reduction in the number of categories covered, expenditure on privileges in 2012 was higher than both MBPF and MSB. Its freezing in the same year and demographic factors (the advanced age of beneficiaries) have reduced the financial burden of this categorical type of assistance.

Regarding the MBPF, the main anti-poverty instrument, the results of the 2009 legal reforms were rather ineffective. Its eligibility coverage continued to decline due to the very low level of the established GMI (guaranteed minimum income), well below the extreme poverty line. Means-testing failures and significant targeting errors continue to affect its adequacy. Its amount, which is related to the GMI, did not cover the basic needs of beneficiaries[38]. In 2015, the GMI was revised and set at 50 percent of the extreme poverty line, and the amount of the MBPF benefit was fixed at the GMI level; however, this non-legislative measure has subsequently depended on budget availability, and the MBPF amount has been slightly below the GMI since 2016.

In contrast to the MBPF, the coverage of the MSB increased relatively quickly (58 percent increase between 2005 and 2015). Its budgetary cost was higher than that of the MBPF until 2015. The amount of the MSB varies between different beneficiary groups, but on average, it tends to be significantly higher than the MBPF (approximately three/four times recently) (figure 6). The larger amounts of MSBs are received by some groups of children or adults with disabilities. The coverage of these groups is otherwise affected by inclusion and exclusion errors due to unequal access and non-transparent practices in the medical certification process[39]. The MSB old-age allowance (for the unpensioned elderly) is meagre, several times lower than the average Social Fund pension.

Figure 6.

Number of beneficiaries and average amount of benefit (MBPF and MSB)

Further changes to the legal framework of social assistance were introduced by a new law on state benefits, which was adopted in 2017. The main novelty of this law was the abolition of means-tested targeting of the MBPF, thus adopting a universal approach. After an intense debate involving both local (including the Parliament) and foreign actors (notably the IMF[40] and the World Bank), the law was amended in 2018 to conform to a system with two types of benefits for families with children:

- The Monthly Benefit for Poor Families with Children (MBPF), called now Ui-Bulogo Komok (UBK) in Kyrgyz, again targeted according to income and asset eligibility criteria; its amount, unchanged between 2016 and 2021[41], continues to be adjusted for residence in the highlands.

- A one-off birth grant for all newborns, called Balaga Suyunchu (BS) in Kyrgyz.

As explained earlier, the COVID-19 pandemic worsened the socioeconomic conditions of a large part of the Kyrgyz population, especially those not covered by social insurance or social assistance. The government, and local private and foreign aid funds had to mobilize various palliative measures, ranging from monetary compensation to food aid. The relief was rather evenly distributed across the socioeconomic strata, with 11 percent of all households receiving it (but just 16 percent of the poorest consumption quintile)[42]. This support has not prevented the sharp increase in poverty levels observed in 2021 and 2022. The impact of recent shocks, including high inflation (14,7 percent in 2022 and 7,3 percent in 2023), has raised serious warnings about the capacity of national social protection systems. As a primary reaction, the amounts of many social benefits increased significantly at the end of 2021 and in 2022. The most favoured were again the majority of MSB recipients, with increases generally of 100 percent of the previous amounts. MBPF-UBK was raised from 810 Soms to 1.200 Soms (about 13.2 €).

B. Scope and challenges of the current antipoverty policy ^

To take stock of the effectiveness of Kyrgyzstan’s national poverty reduction schemes, issues related to their coverage, adequacy, income impact and financing can be examined. Attention needs to be focused on the characteristics of the MBPF-UBK, which is the only programme with a primary anti-poverty objective. However, the role of other welfare schemes, especially pensions, must also be considered. Let us look briefly at some factual aspects of the above issues:

- Coverage. The MBPF-UBK is provided to just over 14 percent of the country’s children. This is less than half the proportion of children (under 18) living in poverty in 2020 (31.8 percent, NSCK data). It has been estimated that almost 60 percent of children in the poorest quintile are excluded from the benefit[43]. Geographically, high poverty areas such as Jalalabad, Batken and Naryn have the highest proportions of households benefiting from MBPF-UBK. However, it is largely absent in urban areas such as Bishkek[44], where high levels of extreme poverty are known to have occurred during the 2020-21 shock.

- Between 2019 and 2021, the number of poor people increased by 71 percent (NSCK data), while the number of MBPF-UBK beneficiaries only increased by 16.5 percent. This reveals the persistent rigidity and drawbacks of means-testing methods, which encouraged their suppression in 2017. The need to adapt and refine targeting methods was evident when they were reinstated in 2018.

- Adequacy. Some remarks have already been made about the scanty level of the MBPF-UBK and its historic benchmark, the GMI. The legal changes adopted in 2018 provide that “the guaranteed minimum income shall be close to the average annual amount of the subsistence minimum”[45]. The MBPF-UBK amount, even after the increase approved in 2022, is very far from this goal. It is equivalent to 19.7 percent of the 2022 subsistence minimum for children under 18 years of age. This level is not conducive to escaping poverty and food insecurity. There is also a significant gap in the amount of the MBS for unpensioned elders: 31.3 percent of the 2022 subsistence minimum for the population of retirement age.

- Impact. In 2021, income from social transfers (mainly MBPF-UBK and MSB) accounted for 4.25 percent of the total income of the poorest household quintile; pensions accounted for 18.1 percent (NSCK data). It is estimated that in 2018, MBPF-UBK reduced the incidence of child poverty by 1.2 percentage points and the overall poverty rate by 0.6 percentage points[46]. This is a much smaller impact than that of pensions, which are estimated to reduce the poverty rate by an average of 20 percentage points[47]. With a large coverage of the elderly population and a relatively high average amount (121.6 percent of the subsistence minimum at the end of 2022), pensions are the key factor in poverty reduction[48].

- Funding.The social benefits budget accounted for 29.2 percent of the total social protection expenditure of the Kyrgyz government in 2021. Most of this total expenditure consisted of budget transfers to the Social Fund[49] to finance the basic component of pensions and other costs (in particular non-contributory pensions for military personnel). The implemented budget shares of the main social benefits in 2021 were as follows: 35.6 percent to the MBPF-UBK, 5.6 percent to the universal birth grant, 38.9 percent to the MSB and 11.0 percent to the compensation of privileges[50]. The weight of the latter has fallen sharply over the last decade[51]. As far as MBPF-UBK and MSB are concerned, there is a slight increase in their weight in terms of GDP: from 0.49 percent and 0.55 percent, respectively in 2011, to 0.53 percent and 0.57 percent in 2021. Together with other lines (universal birth grant, monetised privileges, funeral benefits, boarding houses, administrative costs, etc.), the total expenditure on social assistance amounted to 1.72 percent of GDP in 2021. Spending on active labour market measures for vulnerable groups (including public works) has remained marginal[52].

- Challenges. Overall, a better balance between contributory and non-contributory schemes and, within the latter, between categorical and poverty lines seems suitable. The possible changes are politically complex, given the existing fiscal and sociohistorical constraints (acquired rights). In general terms, the aim would be to achieve a more progressive, efficient, and less fragmented social protection system. More specifically, the main challenges identified in reviews by various international organisations, can be summarised as follows:

The important anti-poverty role of pensions must be preserved. However, their fully budget-financed basic component should be redesigned to be consistent with non-contributory schemes. One option that has been suggested would be to replace the basic pension and the MSB for seniors and disabled adults with a universal, budget-financed social pension[53]. The level of such a pension would have to be socially adequate but also financially sustainable. The burden on the state resulting from the current pension structure may be difficult to sustain in the future, unless strong measures are taken. Among them: greater formalisation of the economy and employment[54], or reducing the burden of non-contributory military pensions[55].

In the area of non-contributory social benefits, equity criteria should be more prominent. While the financial burden of privileges has been significantly reduced, there is still a significant gap between the amounts allocated under the MSB and those under the MBPF-UBK. The latter remains largely disconnected from the subsistence minimum, although the 2018 State Benefits Act was intended to establish a link between them. In addition to increasing its value, the currently limited coverage of MBPF-UBK needs to be expanded. All this would, of course, entail higher costs, but these could be properly calibrated without dramatically disrupting social assistance budgets. The question is whether there are effective anti-poverty instruments in national social protection policies. Pensions help many extended families, but they do not exist or provide tiny amounts in vulnerable situations.

The effectiveness of poverty reduction assistance also depends crucially on the accurate design and implementation of targeting procedures. The latter have been identified as deficient in Kyrgyzstan, and technical efforts are underway to improve them. The prevalence of informal jobs in the country means that some sources of household income may not be verifiable and captured by traditional means-testing methods. In addition, some targeting criteria used thus far in Kyrgyzstan may exclude some of the poorest households[56]. There may be different options for refining targeting methods[57], but the one chosen should be well suited to the Kyrgyz social and institutional context. Another critical factor is the available public capacity to manage the whole cycle of the system: from the collection and processing of information through the targeting and implementing phases to the monitoring and evaluation of results. These capacities need to be developed at both national and local levels, with a coherent division of responsibilities between them[58]. The existing information tools, particularly the so-called ‘household social passport’, need to be improved (with IT resources) and linked to other social databases. A better organized administration of benefits must ensure easy access for claimants, fairness, and transparency in the delivery of benefits. The existing periodic Kyrgyzstan Integrated Household Survey (KIHS) could be used for regular monitoring and evaluation[59].

As a complement to anti-poverty policies, active labour market programmes can promote the productive inclusion of jobless and poor households. In addition to the extension of existing programmes (ad hoc vocational training and public works on local infrastructure), other initiatives are emerging to graduate these households from social assistance to employment or self-employment. Among these, it is worth highlighting the ’social contract‘ programme, which supports income-generating activities for selected low-income families, in principle MBPF-UBK beneficiaries. The social contract is an agreement between these families and the government, whereby the former receive a cash grant to start productive activities, combined with training and coaching to develop a business plan. Other employment initiatives aim to reintegrate migrant workers.

VI. CONCLUDING REMARKS ^

After a difficult post-Soviet transition in the 1990s, Kyrgyzstan’s economy has been recovering since the turn of the century, allowing for favourable but uneven trends in poverty reduction. However, the economy remains vulnerable to exogenous factors such as climate, migrant remittances, and international gold markets. While poverty has tended to decline over the last two decades, it has increased lately, mainly because of the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences (job insecurity, high inflation, etc.). Poverty has traditionally been concentrated in rural areas, but urban poverty has recently risen significantly.

To address the social deterioration of the post-independence years, the national government reintroduced a welfare model, albeit much less generous than in the Soviet era. A key component of this model is the pension system, which covers a large proportion of the elderly population. The non-contributory social assistance component consists of both categorical and poverty-targeted grants, which together reach a relatively small proportion of the population. The whole model is subject to acute financial constraints. The deficit in the contributory pension system is financed by increasing government transfers, which limits the scope for public spending on the social assistance component. Within the latter, spending on benefits for some categories of the population remains higher than on programmes targeting poverty. The result of this scenario is that, despite the role of pensions in reducing poverty, many households, including the most vulnerable, are left behind in terms of social protection. Their situation is aggravated by the limited scope and coverage of free public health services.

Kyrgyzstan’s public finances are under pressure. Revenue collection is relatively robust but not sufficient to avoid public deficits and rising debt. Even within this tight framework, fiscal space could be created for some national social priorities. Options in this sense may exist both on the tax side and through some expenditure reallocations. Among the policy areas that could benefit from these fiscal adjustments, poverty reduction should take a prominent place. The effectiveness of Kyrgyzstan’s national pro-poor schemes has thus far been insufficient in terms of coverage, adequacy, income impact, and financing. The weight of these schemes in the social protection system should be increased to achieve greater progressivity. A better balance between contributory and non-contributory benefits seems suitable. Poverty-targeted benefits should form a key part of non-contributory social assistance. However, such distributional changes, as well as those related to taxation, challenge deep-rooted interests and may be politically complex.

Bibliography ^

Atamanov, A. & Van den Berg, M.: “Participation and returns in rural nonfarm activities: evidence from the Kyrgyz Republic”, Agricultural Economics, num. 43, 2012, pp. 457–469.

Gassmann, F. & Timar, E.: Scoping study on social protection and safety nets for enhanced food security and nutrition in the Central Asia region. Country report: the Kyrgyz Republic, World Food Programme, 2018.

ILO/International Labour Organization: Social Protection Assessment-Based National Dialogue. Towards a Nationally Defined Social Protection Floor in the Kyrgyz Republic, 2017.

ILO/International Labour Organization: World Social Protection Report 2020–22: Social protection at the crossroads - in pursuit of a better future, Geneva, 2021.

ILO/International Labour Organization: Diagnostic report Transition from informal to formal employment: Extension of social protection schemes (maternity and unemployment) in Kyrgyzstan, 2023.

ILOSTAT/ International Labour Organization: Statistics, https://ilostat.ilo.org/.

International Organization for Migration (IOM): Mapping Report of the Kyrgyz Diaspora, Bishkek, 2022.

Kayani, F.N.: “Role of foreign remittances in poverty reduction: A case of poverty-ridden Kyrgyzstan”, Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, vol. 15, issue 3, 2021, pp. 545-558.

Life in Kyrgyzstan study, https://lifeinkyrgyzstan.org/

Mogilevskii, R.; Abdrazakova, N.; Bolotbekova, A.; Chalbasova, S.; Dzhumaeva, S. & Tilekeyev, K.: The outcomes of 25 years of agricultural reforms in Kyrgyzstan. Discussion Paper num. 162, IAMO-Leibniz, 2017.

NSCK/National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic, https://stat.kg/en/statistics

OECD: Social Protection System Review of Kyrgyzstan, OECD Development Pathways, 2018.

UIS-UNESCO Institute for Statistics, http://data.uis.unesco.org/

WDI/World Development Indicators, World Bank, https://databank.worldbank.org/.

WHO/World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/data/data-collection-tools/

WIDE-UNESCO. MICS-Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2014. https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/wide-inequalities-education.

[*] El artículo no ha sido desarrollado al amparo de las actividades de un grupo de investigación.

[1] In 1991, these USSR transfers still represented 12.2 percent of the Kyrgyz GDP and 35.2 percent of the revenues of the consolidated budget (IMF/International Monetary Fund, “Kyrgyz Republic”, IMF Economics Reviews, num. 12, 1993).

[2] The country has been classified as a lower-middle income country (World Bank criteria) since 2014, with a GNI per capita of USD 1,440 (2022). However, there are large territorial disparities when comparing per capita income data between its seven regions (oblasts).

[3] In Soviet times, in addition to the predominant state (sovkhozes) and collective (kolkhozes) farms, peasants were allowed to have small home gardens and a limited number of animals. During frequent supply shortages, these individual assets could ensure food subsistence.

[4] Steimann, B.: Making a Living in Uncertainty. Agro-Pastoral Livelihoods and Institutional Transformations in Post-Socialist Rural Kyrgyzstan, Human Geography Series / Schriftenreihe Humangeographie, vol. 26, 2011.

[5] Steimann, B.: op. cit.

[6] Mestre, I.; Ibraimova, A. & Azhibekov, B.: “Conflicts over pasture resources in the Kyrgyz Republic”, Research Report, CAMP Alatoo-ACTED-USAID, 2013.

[7] FAO: Smallholders and family farms in Kyrgyzstan. Country study report 2019, Budapest, 2020.

[8] NSCK/National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic-Ministry of Health: “Demographic and health survey”, 2013.

[9] Food prices increased by 18 percent in 2021, after a poor harvest, but have continued to rise in 2022 and 2023 (16.2 percent and 8.4 percent, respectively) (NSCK data). By December 2022, more than 15 percent of households were acutely food-insecure (WFP/World Food Programme: “Kyrgyz Republic Country Brief January 2023”, 2023).

[10] Hatcher, C. & Thieme, S.: “Institutional transition: Internal migration, the propiska, and post-socialist urban change in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan”, Urban Studios, num. 53 (10), 2016, pp. 2175-2191.

[11] In 2018, the number of Kyrgyz citizens with migration registration in Russia was approximately 640,000, 35,000 in Kazakhstan, 30,000 in Turkey and 30,000 in various other countries (IOM/International Organization for Migration: “Mapping Report of the Kyrgyz Diaspora”, 2022). However, the actual numbers could be much higher due to unregistered migrants (Murzakulova, A.: Rural Migration in Kyrgyzstan: Drivers, Impact and Governance, Research paper nr 7, 2020 University of Central Asia, Gradual School of Development).

[12] According to ILOSTAT, the average salary in Russia in 2021 (in 2017 USD PPP, purchasing power parity terms) was 72% higher than in Kyrgyzstan.

[13] Vakulenko, E. & Leukhin, R.: “Wage discrimination against foreign workers in Russia”, Russian Journal of Economics, num. 3, 2017, pp. 83-100.

[14] KNOMAD/Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development, https://www.knomad.org/data.

[15] Karymshakov, K.; Abdieva, R. & Sulaymanova, B.: “Worker’s Remittances and Poverty in Kyrgyzstan”, 2014. A paper presented at the International Conference on Eurasian Economies, Skopje, Macedonia.

[16] World Bank: Kyrgyz Republic Poverty and Economic Mobility in the Kyrgyz Republic. Some insights from the ‘Life in Kyrgyzstan Survey’, Report no. 99775-KG, 2015.

[17] Zhunusova, E. & Herrmann, R.: “Development Impacts of International Migration on ‘‘Sending’’ Communities: The Case of Rural Kyrgyzstan”, The European Journal of Development Research, num. 30, 2018, pp. 871-891. In fact, the increase in gross agricultural output between 2001 and 2020 (NSCK) was higher than the national average in oblasts such as Batken (particularly for crops) and Jalalabad (particularly for livestock), which receive meaningful remittances.

[18] Ibralieva, K. & Mikkonen-Jeanneret, E.: Constant Crisis: Perceptions of Vulnerability and Social Protection in the Kyrgyz Republic, HelpAge International, 2009.

[19] It makes sense to pay attention to food in a country where segments of the population often face food security and nutrition problems. However, some analysts suggest that as remittances grow, spending on home improvements, durable goods and traditional celebrations increases, rather than on food.

[20] WFP/World Food Programme & International Organization for Migration: “Migration Food Security and Nutrition in the Kyrgyz Republic”, 2021.

[21] Gao, X.; Kikkawa, A. & Kang, J. W. “Evaluating the impact of remittances on human capital investment in the Kyrgyz Republic”, ADB economics, Working paper, num. 637, 2021.

[22] UNICEF: Multidimensional Poverty Assessment for the Kyrgyz Republic, 2020a. The methodology used in this UNICEF study is based on five broad indicators of social deprivation (monetary poverty, education, health, food security, and housing), each with a similar weight (20 percent).

[23] In terms of social outcomes, the very synthetic HDI (Human Development Index) for Kyrgyzstan has risen moderately from 0.640 in 1990 (0.620 in 2000) to 0.701 in 2022 and remains below the Central Asia average (0.731) (UNDP/United Nations Development Programme: “Human Development Report 2023-24”, 2024).

[24] The group of Caucasus-Central Asia countries is composed of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

[25] Despite the increasing trend in education expenditure in Kyrgyzstan, learning outcomes improved only slightly and remain relatively low compared to other Caucasus-Central Asia countries. Problems of insufficient quality of teaching and pedagogic methods have been often raised (Dean, B.L.; Hung, W.; Papieva, J. & Muibshoev, A.: Education for the 21st Century in Kyrgyzstan: Current Realities and Roadmap for Systemic Reform, University of Central Asia. Education Improvement Programme, 2021).

[26] The UIS-UNESCO and WHO figures on the relative budget allocations for education and health in Kyrgyzstan are lower than those reported by the national statistics (NSCK) but are retained to ensure harmonization with the other countries.

[27] ADB/Asian Development Bank, “Key Indicators for Asia and the Pacific 2022”, Economy Tables, 2022, https://kidb.adb.org.

[28] The data in figure 5 refer to tax-funded social protection spending, including budget transfers to the pension system but excluding spending of this system funded by social contributions from employers and workers.

[29] WHO/World Health Organization: Health financing in Kyrgyzstan: obstacles and opportunities in the response to COVID-19, Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2021.

[30] A significant part of the current health expenditure (40.6 percent in 2021, WHO/World Health Organization) is borne by households at the national level.

[31] Jakab, M.; Akkazieva, B. & Habich, J.: Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Kyrgyzstan, Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2018.

[32] According to an OECD study (OECD: “Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific: Strengthening Tax Revenues in Developing Asia”, 2022), total taxes on income and profits in Kyrgyzstan accounted for 21.7 percent of public revenues (excluding social contributions) in 2020, the lowest level in Asia after Laos.

[33] IMF. “Revenue mobilization for a resilient and inclusive recovery in the Middle East and Central Asia”, DP/2022/013, 2022. The IMF study refers to 32 countries in northern Africa, the Middle East, the Caucasus, and Central Asia.

[34] Ismailakhunova, S.: “Shall High Income Earners Pay More Taxes in The Kyrgyz Republic”,Ege Academic Review, vol. 14 (4), 2014, pp. 499-507.

[35] IMF/International Monetary: “Kyrgyzstan: 2019 Art IV consultation, Selected issues, Report no. 19/209”, Kyrgyz Republic: unleashing the potential of the electricity sector, 2019.

[36] IEA/International Energy Agency: “Kyrgyz Republic Energy Profile 2020”, 2021.

[37] World Bank: “Kyrgyzstan -Social protection in a reforming economy”, report num. 11535-KG, 1993.

[38] Gassmann, F. & Zardo, L.: “Kyrgyz Republic. Analysis of Potential Work Disincentive Effects of the Monthly Benefit for Poor Families in the Kyrgyz Republic”, World Bank Report no. 99776 KG, 2015.

[39] OECD: Social Protection System Review of Kyrgyzstan, OECD Development Pathways, 2018.

[40] In December 2017, the IMF introduced the following benchmark in the review of its Extended Credit Facility: “Submit to Parliament amendments to the recently adopted Law on State Subsidies of the Kyrgyz Republic (introducing the universal child allowance) to restore targeting to the most vulnerable”. The results of a simulation study coordinated by WFP (WFP/World Food Programme: “Changing the law on state benefits. The impact of lifting the Monthly Benefit for Poor Families (MBPF) in the Kyrgyz Republic”, 2018) predicted unfavourable consequences of the 2017 universal approach, both in terms of poverty and food security. Other elements of the debate between the option of universal aid and that of selective aid, subject to targeting, appear in these divergent documents of two other international bodies: 1) World Bank: “Recent developments in improving targeting and administration of social assistance programs in Kyrgyz Republic and a proposed roadmap”, 2018; 2) UNICEF: “Universal Child Grant Benefit Studies: The Experience of the Kyrgyz Republic”, 2019.

[41] The MBPF-UBK amount (810 Soms) remained below the GMI, which increased from 900 (2016) to 1,000 Soms in 2019. It was also well below the extreme poverty line (2,544 Soms in 2021). 1 Som is approximately equivalent to 0.011 €.

[42] WFP/World Food Programme: “Poverty, Food Security and Nutrition Analysis in the Kyrgyz Republic”, 2021.

[43] Gassmann, F. & Timar, E.: Scoping study on social protection and safety nets for enhanced food security and nutrition in the Central Asia region. Country report: the Kyrgyz Republic, World Food Programme, 2018.

[44] Only 2.3 percent of households are covered by MBPF-UBK in urban areas (WFP/World Food Programme, 2021, op. cit.). In Bishkek, 9.8 per cent of the total population lived in extreme poverty in 2021 (NSCK).

[45] The subsistence minimum level is the value of the basic package of food and non-food goods and services needed to live and be healthy. It is estimated quarterly for different population groups.

[46] UNICEF: Position paper on targeting options for social assistance programme for poor families with children, 2020b.

[47] WFP/World Food Programme, 2021, op. cit.

[48] Nevertheless, 43 percent of Social Fund pensions were below the subsistence level at the end of 2022, some of them significantly (Social Fund: Pensioners receiving pensions below and above the pensioner’s minimum subsistence level, 2023).

[49] Complementing the insufficient revenue from social contributions (employers and employees), budget transfers financed 39.2 percent of Social Fund expenditure in 2021, equivalent to 8.4 percent of GDP.

[50] Ministry of Finance of the Kyrgyz Republic: Explanatory note to the report on state budget execution of the Kyrgyz Republic for 2021, 2022.

[51] The ratio of privileges to GDP was 0.93 percent in 2011 and 0.16 percent in 2021.

[52] ILO/International Labour Organization: Diagnostic report Transition from informal to formal employment: Extension of social protection schemes (maternity and unemployment) in Kyrgyzstan, 2023.

[53] OECD, 2018, op. cit.

[54] ILO/International Labour Organization, 2023, op. cit.

[55] OECD, 2018, op. cit.

[56] The OECD report (2018) mentions the case of poor households with some land who are excluded from the MBPF, even if they are unable to use their plots. Other problems are related to the complicated and costly process of applying for benefits.

[57] Grosh, M.; Leite, P.; Wai-Poi, M. & Tesliuc, E. (eds.): Revisiting Targeting in Social Assistance: A New Look at Old Dilemmas, World Bank, 2022, doi:10.1596/978-1-1814-1. This study suggests the HMT (hybrid means test) for Kyrgyzstan. Under this method, in addition to the verifiable part of the income, another part can be imputed according to sociodemographic indicators.

[58] In 2018, it was decided to transfer the responsibility for collecting and processing MBTF-UBK applications from local authorities to the district offices of the relevant ministry, with the former retaining other cooperation tasks. Unfair practices and even corruption in the selection of beneficiaries at the local level had been identified by the central services (Gassmann & Timar, 2018, op. cit.). According to recent reports, ‘informal’ payments to obtain social assistance benefits have continued (UN Human Rights Commission, “Document A/HRC/53/33/Add.1”, 2023).

[59] UNICEF, 2020b, op. cit.