Learning to Collaborate. Preparing students for practice in multi-disciplinary teams / Aprender a colaborar. Preparar a los estudiantes para la práctica en equipos multidisciplinares / Aprendendo a colaborar. Preparando os alunos para a prática em equipes multidisciplinares

Colvin, Wendy. University of the West of England, School of Architect & Environment, Bristol, United Kingdom, Wendy.Colvin@uwe.ac.uk https://orcid.org/0009-0008-1911-3829

Received: 23/06/2025

Accepted: 13/09/2025

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/astragalo.2025.i39.10

Abstract

UWE’s College of Arts, Technology and Environment offers awards related to most construction disciplines, enabling interdisciplinary collaborative working that reflects industry. In Collaborative Practice students from disciplines relating to the construction industry work collaboratively, to challenge concerns highlighted in various industry reports. Guided by construction professionals, students develop and apply a range of interdisciplinary skills. The academic aim of the module develops an understanding of the roles and responsibilities of respective members of the construction team and their interactions through different stages of projects, provided through a mixture of lectures and group workshop activities. The assessment comprises a group presentation in mixed-discipline groups and a collection of reflective writing on academic learning and collaborative working. This module makes a concerted effort to include everyone. Student background is diverse in not only discipline, but in ethnicity and experience. The module team is aware of the distrust that might exist with preconceived ideas about ‘others,’ whether other professionals or other backgrounds. A soft module aim is to address those notions directly and to encourage healthy, collaborative working across the team. This paper will explore how the module enables collaboration and reflexive practice, and as a result, builds student confidence, promotes inclusion and provides preparation for working in multi-disciplinary teams.

Keywords. built environment, group work, higher education, interdisciplinary, reflective practitioner

Resumen

La Facultad de Artes, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente de la UWE ofrece titulaciones relacionadas con la mayoría de las disciplinas de la construcción, lo que permite un trabajo colaborativo interdisciplinar que refleja la realidad del sector. En la asignatura Práctica colaborativa, los estudiantes de disciplinas relacionadas con el sector de la construcción trabajan en equipo para abordar los retos que se plantean en diversos informes del sector. Guiados por profesionales de la construcción, los estudiantes desarrollan y aplican una serie de habilidades interdisciplinares. El objetivo académico del módulo es desarrollar la comprensión de las funciones y responsabilidades de los respectivos miembros del equipo de construcción y sus interacciones a lo largo de las diferentes etapas de los proyectos, lo que se consigue mediante una combinación de clases magistrales y actividades de taller en grupo. La evaluación consiste en una presentación en grupo en grupos multidisciplinares y una recopilación de escritos reflexivos sobre el aprendizaje académico y el trabajo colaborativo. Este módulo hace un esfuerzo concertado para incluir a todo el mundo. Los antecedentes de los estudiantes son diversos, no solo en cuanto a disciplina, sino también en cuanto a origen étnico y experiencia. El equipo del módulo es consciente de la desconfianza que puede existir con ideas preconcebidas sobre ‘los otros’, ya sean otros profesionales u otros orígenes. Un objetivo secundario del módulo es abordar directamente esas nociones y fomentar un trabajo saludable y colaborativo en todo el equipo. Este artículo explorará cómo el módulo permite la colaboración y la práctica reflexiva y, como resultado, fomenta la confianza de los estudiantes, promueve la inclusión y prepara para trabajar en equipos multidisciplinares.

Palabras clave. entorno construido, trabajo en grupo, enseñanza superior, interdisciplinariedad, profesional reflexivo

Resumo

A Faculdade de Artes, Tecnologia e Meio Ambiente da UWE oferece cursos relacionados à maioria das disciplinas de construção, permitindo um trabalho colaborativo interdisciplinar que reflete a realidade do setor. No curso Collaborative Practice (Prática Colaborativa), os alunos de disciplinas relacionadas ao setor de construção trabalham em equipes para enfrentar os desafios apresentados por vários briefings do setor. Orientados por profissionais da construção, os alunos desenvolvem e aplicam uma série de habilidades interdisciplinares. O objetivo acadêmico do módulo é desenvolver uma compreensão das funções e responsabilidades dos respectivos membros da equipe de construção e suas interações ao longo dos diferentes estágios dos projetos, o que é alcançado por meio de uma combinação de palestras e atividades de workshop em grupo. A avaliação consiste em uma apresentação em grupos multidisciplinares e uma coleção de textos reflexivos sobre o aprendizado acadêmico e o trabalho colaborativo. Este módulo faz um esforço concentrado para incluir todos. As origens dos alunos são diversas, não apenas em termos de disciplina, mas também em termos de etnia e experiência. A equipe do módulo está ciente da desconfiança que pode existir com ideias preconcebidas sobre ‘os outros’, sejam eles outros profissionais ou outras origens. Um objetivo secundário do módulo é abordar diretamente essas noções e incentivar o trabalho saudável e colaborativo em toda a equipe. Este artigo explorará como o módulo possibilita a colaboração e a prática reflexiva e, como resultado, aumenta a confiança dos alunos, promove a inclusão e os prepara para trabalhar em equipes multidisciplinares.

Palavras-chave: ambiente construído, trabalho em grupo, ensino superior, interdisciplinaridade, profissional reflexivo

1. Introduction

The building industry requires that multi-disciplinary teams work together, with each discipline bringing its own specific knowledge and skills to projects. Collaboration is important. Imparting what this is to students and its significance in HE is challenging.

At the University of the West of England (UWE) in Bristol there is a long tradition of inter-disciplinary teaching in a true built-environment school. The School of Architecture & Environment offers undergraduate programmes related to most of the key construction disciplines, which allows us to reflect interdisciplinary collaborative working that our graduates will experience in practice. Our undergraduate students have long been required to take modules that are inter-disciplinary in nature and that require them to work with students on other built environment programmes. Collaborative Practice is the latest module building on that tradition. It is a module that teaches students not only about the industry but develops intra-personal and inter-personal skills. Indeed, there is as much emphasis placed on these as there is on more concrete aspects of practice. According to Sisti & Robledo (2021), interdisciplinary collaboration enhances learning outcomes by bringing diverse perspectives and expertise, which aligns with the goals of our Collaborative Practice module.

1.1 Background

The construction industry in the UK contributes approximately 6% to the UK’s GDP. It is a significant sector for economic growth in the country. It is a sector that accounts for about 10% of all jobs in the country, which means it is a significant source of tax revenue for the treasury. (HM Government 2013) It is an important industry and one that successive governments rely on as a measure of a healthy economy.

It is also an industry that can be beset with problems from adherence to regulation to compliance with fire-and-life safety of buildings to imparting value to clients to adversarial relationships of those involved. Successive governments have commissioned reports going back more than thirty years reviewing the industry and suggesting recommendations to improve quality and efficiency (Latham, 1994 and Egan 1998). More recent reports have charted the progress of early suggestions and through these there is a push for more effective ways of working and an increasing use of the word collaboration (HM Government 2013). The organisation, Constructing Excellence, was established in 2003 to champion the reforms suggested and to promote collaboration in the industry.

Construction is a collaborative activity –only by pooling the knowledge and experience of many people can buildings meet the needs of today, let alone tomorrow. But simply bringing people together does not necessarily ensure they will function effectively as a team. Effective teamwork does not occur automatically. It may be undermined by a variety of problems such as lack of organisation, misunderstanding, poor communication and inadequate participation. (Constructing Excellence 2004, 4)

This context is the backdrop to the inter-disciplinary working at UWE and how we introduce the module, Collaborative Practice. This paper will focus on the group work and the reflective practice aspects of the module and the pedagogy we have developed over ten years.

1.2 Method

This work presents a particular pedagogical approach that has developed through the Collaborative Practice module at UWE. The methodological approach involves a review of the need for collaborative interdisciplinary teaching, for reflexive practice, and similar modules delivered in a handful of other UK higher education institutions. It will present the Collaborative Practice module as a case study as a rare and exemplary model of undergraduate interdisciplinary education in the built environment. It will utilise some initial qualitative findings from the author’s research project (Colvin et al 2024) to underpin the module’s effectiveness

1.3 The pedagogical context for interdisciplinary teaching and reflexive practice

The introduction to this paper sets out the expectation from industry for increased collaboration. The challenge is how to deliver this to derive the benefits of this type of working. Professional standards are shifting to accommodate this thinking, including through changing competency frameworks and professional codes of conduct. For example, the UK Architects Registration Board (ARB) has undertaken recently a thorough review of the architectural education framework by updating its competencies for qualification (ARB 2023) and has overhauled its Architects Code: Standards of Conduct and Practice (ARB 2025).

Education frameworks need to develop specific skills of their students to meet industry needs, and this is being increasingly recognised. A recent study by Cooper et al. (2025) outlines the need for a “new multidisciplinary built environment professional” with integrated knowledge across architecture, engineering, and environmental design. Additionally, the chapter by Jeddere-Fisher et al. (2025) stresses the importance of stakeholder engagement, systems thinking, and sustainability literacy in response to climate and social challenges. Table 1 identifies skills that can be developed in interdisciplinary development and associated, derived benefits.

|

Skill |

Benefits |

|

Communication |

Essential for conveying ideas across disciplines and to stakeholders |

|

Teamwork & Collaboration |

Core to multi-disciplinary practice; fosters mutual respect and shared goals |

|

Professional Identity |

Helps students understand their role and value within a wider project team |

|

Interdisciplinary Thinking |

Enables integration of diverse perspectives for holistic decision-making |

|

Systems Thinking |

Encourages understanding of complex, interconnected urban and environmental systems |

|

Stakeholder Engagement |

Builds empathy and negotiation skills; vital for inclusive and responsive design |

|

Sustainability Literacy |

Prepares students to address climate, ecological, and social challenges |

|

Critical Reflection |

Supports personal growth and deeper learning from collaborative experiences |

|

Leadership & Initiative |

Encourages proactive problem-solving and responsibility in team settings |

|

Digital & Visual Literacy |

Enhances communication through modelling, sketching, and digital tools |

Table 1. Summary outline of skills for interdisciplinary built environment modules

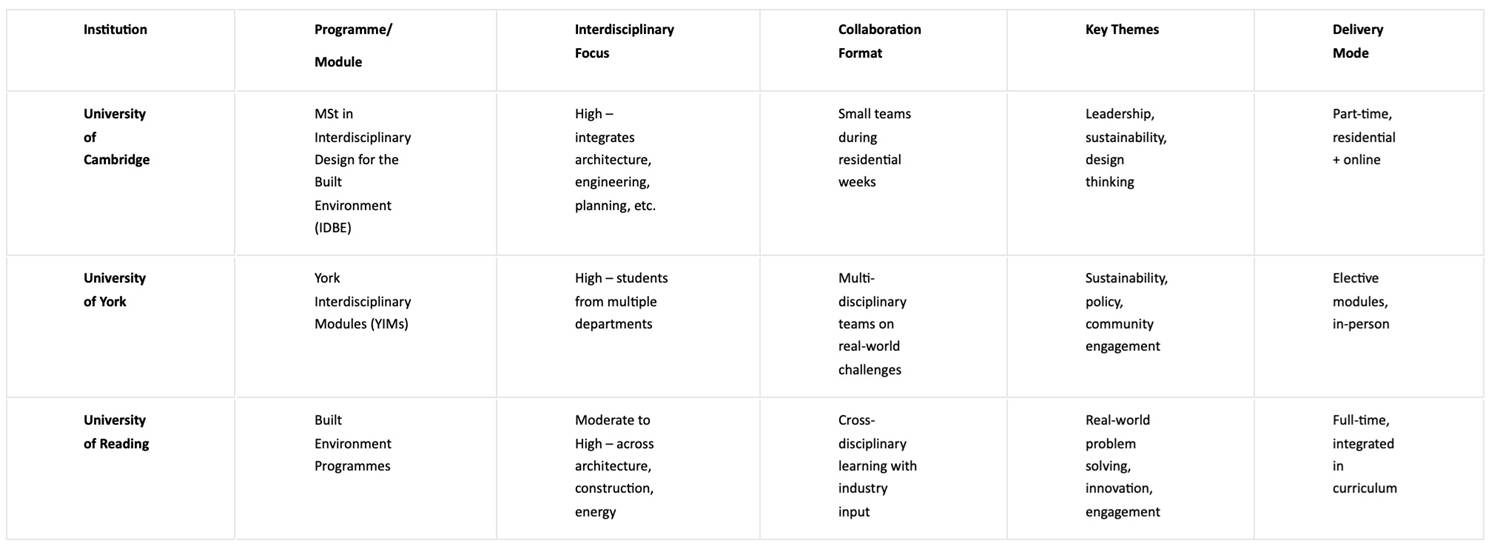

Some built environment schools in higher education are responding to the challenge and are offering interdisciplinary modules. These can be found at University of Cambridge, University of Reading and University of York and their qualities are summarised in Table 2. These provide team-based learning (Cambridge), industry collaboration (Reading), and community engagement (York) and exemplify the benefits of skills development in integrating collaboration, sustainability literacy and interdisciplinary thinking. What is notable about these is the postgraduate focus and in the case of University of York the modules are taken as electives.

Table 2. Comparison of examples of interdisciplinary built environment modules

Reflective writing plays a critical role in helping built environment students integrate their learning experiences with professional development. If used in conjunction with interdisciplinary delivery, it enables them to see the relevance of their discipline role in the wider industry. It is not merely a pedagogical tool but a bridge between academic learning and industry practice.

Reflective writing enables students in built environment disciplines to engage in problem-solving and critical thinking, especially when dealing with complex, real-world scenarios (McCarthy 2011). Drawing on experiential learning theory, learning is incomplete without reflection, as it allows students to generate insights and apply them to future situations (Gibbs 1988).

While some may question whether reflective writing is the most effective method, it offers unique benefits. It encourages individual accountability within group work, providing a structured format for students to critically assess their contributions and challenges. It is useful in charting individual learning and for introducing the notion of Continuing Professional Development (CPD). Many professional bodies expect reflexive practice as part of their CPD requirements. It aligns with professional standards, such as the Royal Town Planning Institute’s Assessment of Professional Competence, which includes reflective practice as a core component (McCarthy 2011), and the ARB’s CPD scheme.

Alternative methods —such as video diaries, peer interviews, or facilitated group reflections— can complement written reflection. However, written reflection remains a scalable, assessable, and introspective format that supports deep learning and professional growth.

2. Case Study, Collaborative Practice module

Collaborative Practice is an undergraduate module at UWE which provides an opportunity for students to understand, develop and apply a range of interdisciplinary skills and ways of working. To reinforce the multi-disciplinary nature of practice in the development sector, students undertake roles that are appropriate to the learning they have acquired on their individual programmes and the roles they are likely to undertake in their future professional lives. The aims of the module are to equip the students with the ability to recognise the range of choices implicit at the different stages of the development process and to make informed and appropriate decisions based on the assessment of relevant factors and data. It is a core module for eleven built environment programmes, including architectural, surveying, services engineering, planning, property development, and project management students. It is one of the largest modules in our school, with approximately 300 students and a team of 20 multi-discipline tutors.

The module highlights interdisciplinary working, with students undertaking their own roles for working together. It points students to their future and for working in the industry. It incorporates an element of reflective understanding to develop awareness of own professional development needs. We communicate these aims to the students as being two-fold. They learn about how to work in groups, and they develop an ability to reflect on their own learning. Two significant aspects of the module include group work and reflective writing. These are challenging for the students. We know that students do not like group work, because they have had poor experiences of this previously. Likewise, they have not encountered reflective writing and therefore lack confidence in this. We feel both aspects are important in developing them as young professionals, so quite a bit of the tangential teaching focuses on these two aspects.

2.1 Module structure

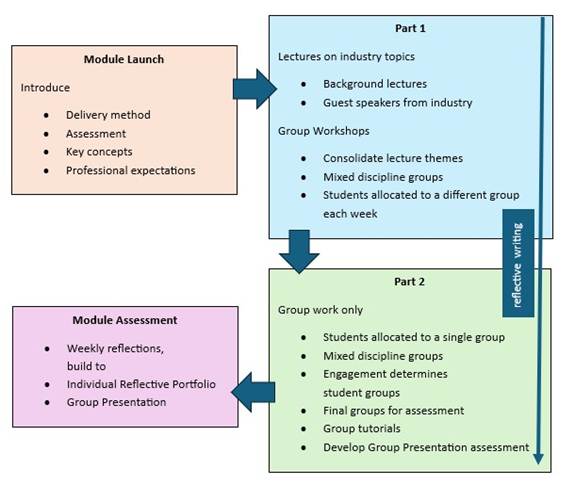

Collaborative Practice is a 15-credit (7.5 ECTS), Level 6 module that runs in Semester 1. It is delivered in two parts, with the first part containing lectures and group workshops every week. The second part is devoted to group work only with tutorials provided by module tutors. Module Learning Outcomes are assessed in two Tasks, a Group Presentation and Individual Reflective Portfolio. The structure of the module can be seen in Figure 1 and specific aspects are detailed below.

Fig. 1 Module Structure Diagram. Wendy Colvin, 2025

In Part 1, lectures provide insight about the industry, following a clear and logical structure. Each week adopts a different theme, for example disciplines in the room, clients and project types, risk and value, procurement, with a background-lecture & guest-speaker from industry. Students appreciate the input from industry, which gives clear and tangible examples of the background material and the weekly theme. They report that they like the different viewpoints on collaboration provided. These introduce new ways of thinking that they have not considered previously about delivering successful projects.

Specific lectures on group theory are delivered at key, strategic points in the semester. These include different team formation models, aspects of group leadership, team role categories for effective teams, and managing dysfunctions in teams. We introduce theories and strategies that focus on individual behaviours to develop interpersonal skills. As part of the latter, we introduce the notion of reflexive practice providing an overview of a variety of models, aspects of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, problem solving, effective communication strategies and a compassionate approach. Students may have encountered some of this material elsewhere. The difference is that we combine it with practical examples through the guest speaker along with the opportunity to practice in the group work aspect of the module. The result is that students think more carefully about their behaviour and their reactions to others’ behaviours. They develop an appreciation “that everyone shares the same goal, so getting frustrated on interpersonal relationships is not beneficial. Listening and understanding them with compassion will help you move on.“ (Colvin et al 2024)

In Part 1, we run Group Workshops, with students allocated to a different mixed-discipline group each week. Worksheets are provided, which include tasks associated with the topic of the week. To facilitate useful discussion, students consider one of five project scenarios provided by the module team. These scenarios are based on real projects and represent a range of types and complexities. The workshop provides students the opportunity to consolidate and extend their learning about the theme, through completing specific tasks, e.g. undertaking a risk assessment in risk and value week. The multi-disciplinary make-up of the groups allows students to share their own discipline-specific knowledge to develop greater understanding of the weekly theme and thus facilitates peer-to-peer learning. Wang (2025) emphasizes the benefits of student-led approaches in fostering engagement and deeper learning, which is reflected in our module's emphasis on peer-to-peer learning. The Workshops serve to break down barriers between the different groups of students. They learn that “you do not need to know everything, having different disciplines allows you to ask questions that you might not know the answer to.” (Colvin et al 2024) They develop professional networking skills which further improves their self-efficacy of working in groups, “How to be proactive in introductions was something I was not great at before, but with new groups each week it became natural.” (Colvin et al 2024)

A significant aspect of the module involves group work. Students report that their dislike of group work in part stems from poor previous experience, which interferes with their ability to see the benefits. These benefits are essential when considering the reality of the industry in which, as graduates, these students will be working in often complex, multi-disciplinary teams. We address this poor experience directly, by acknowledging it and addressing it in the lecture delivery and, in addition, through weekly, individual learning extensions. UWE’s Careers and Enterprise Service has developed a useful, self-directed careers toolkit, that students can complete to enhance their employability. Included within this toolkit are a range of self-diagnostic, assessments that focus on specific inter-personal skills, e.g. assertiveness, workplace culture, motivation at work and emotional control. We have borrowed a selection of these that are most appropriate to the aims of the module and aligned them to the weekly themes. We encourage the students to take two assessments each week during the lecture delivery and to discuss their reflections on these in the group workshops. The aim is to develop these skills gradually over the semester. There is strong indication that many students take these assessments from what they report in their feedback on the module. They identify strongly with the results and use them to consider how to improve specific interpersonal skills.

Part 2 is reserved for group work only and the focus shifts to the Group Presentation assessment. The Module Leader assigns the students to multi-disciplinary groups of between six to eight students. Experience tells us that this is a perfect number to reduce social loafing and to ensure that all voices are heard. Groups are assigned a pair of module tutors, and they meet with them every week for tutorials. As with Workshops in Part 1, worksheets for each week’s meeting are provided, to assist the development of the Group Presentation. These include a carefully chosen tasks each week to focus the groups’ efforts. The Group Presentation requires the students to demonstrate collaboration in the industry. To make this more tangible, groups are required to select one of the five scenarios with which they have worked all semester and build a group presentation around that. This is their first task as a group, to identify which scenario they will use.

We acknowledge students do not like group work. We know one of their concerns is about engagement of other members of the group. We address this by configuring groups based on student engagement with the module. We track attendance and completion of weekly tasks throughout the semester with each point of engagement scoring one point. The final tally of engagement points helps to determine the groups that students are placed into. High scoring students are placed with other high scoring students. Students like this; they think it is fair. Of course, engagement with the module alone does not determine the final groups. This module is preparing students for interdisciplinary practice, so the groups need to reflect the multi-disciplinary nature of the module. As well as engagement, other factors determine the final group make-up, including discipline, gender and international/home student status. The aim is for maximum diversity across every group.

2.2 Module Assessment

There are two items of assessment for this module, a group presentation and an individual, written assignment. Both items assess the collaborative working of the module, but in different ways. Because this is a Level 6 module, it seems unfair to assess the module in group work alone. The individual, written assignment carries the larger portion of the overall module mark. This is appropriate and it has the net effect of tempering the group marks, which tend to be excellent. It allows module marks that reflect academic ability, which is appropriate for a mark contributing to an overall award category.

The written assignment is an Individual Reflective Portfolio. Reflective writing is an important professional skill and required by many professional bodies as part of professional development and Continuing Professional Development CPD). Schön (1983) and Moon (2004) highlight the significance of reflective practice in professional development, supporting the inclusion of reflective writing in our module. We set weekly work for students to build this portfolio over the semester using Weekly Reflective Logs, through which students document their learning from their self-directed study, the diagnostic assessments, the lectures and the workshops. Each week of the semester we provide question prompts to assist with drafting the Weekly Log. The Logs are used as part of the engagement tracker discussed previously.

The module team samples the Logs and compiles a Powerpoint of selected, anonymised excerpts to share with the cohort at the beginning the following week’s lecture. This allows us to provide weekly, formative feedback on the preparation of the final written assignment. It means we can illustrate good reflective writing and exemplify aspects that should be included in the final assignment. Some students have used these reflective models previously. However, they seem to have lacked an opportunity to use these in a more pragmatic and professional context. Students indicate that their use here is entirely relevant for understanding their own development needs.

The Weekly Reflective Logs inform the Individual Reflective Portfolio. The Portfolio contains three parts, including a reflective statement, an appendix with four Weekly Reflective Logs and associated Workshop worksheets, and a list of references. The reflective statement requires reflection on two aspects of the module, including academic learning and approach to collaborative working. The practice of reflective writing over the semester builds confidence in preparing this statement. Students are expected to review their Logs to identify two themes upon which to reflect their learning. They could reflect on prior learning and consider this against what they learned from the lectures, both the background and guest speakers. In addition, they are expected to reflect on the group work across the semester and how discipline-specific knowledge informed that work. They should consider how their approach to group work changed over the semester. They should pull these strands together to identify their discipline role, how it interacts with other disciplines, and where their place in the industry sits.

The Group Presentation is a collaborative assessment. Groups identify one scenario from the five they used throughout the semester, and they build a presentation around that scenario. Each of the scenarios includes some key information about a project, including type, scope, and complexity. It lists a range of simple and complex issues with which the team might need to respond, relating to funding, programme implications, key events and activities. The groups need to select one or two issues from the scenario and use the disciplines in the team to demonstrate how this issue would be managed in a project, showing good collaboration. The presentation can take whatever form the group decides, creating a very broad brief which worries some of the students taking the module. However, this is where the multi-discipline affect is apparent, because this is where the architectural students take the lead. Because of the scenario nature of the assignment, most groups try to replicate an activity from practice in their presentations. Most adopt some form of role play, typically enacting a design team meeting or similar. Other approaches have been used such as a game show or an expert-panel question time.

The Group Presentations are held in a single day. Groups are assessed by pairs of tutors in separate panels, with each assessing up to six groups across the day. Groups deliver their presentations to their tutors with other student groups attending as an audience. Presentations are limited to eight minutes, and this is followed by questions and comments from the assessing tutors and attending students and lasts no more than ten minutes. Although it is a controlled assessment, it takes on a celebratory atmosphere as it is the culmination of the module.

Groups are awarded marks by their tutors, using a marking rubric that assesses the response to the scenario, the collaborative effort of the group, the presentation format and the group responses to questions. . It is interesting to note that student engagement with the module does not necessarily affect the marks. Low-engaged groups can score as high or higher than those with high engagement. Generally, all students in the group receive the group mark. This is another aspect of group work that students find unfair. To address this, we require students to complete a Peer Review of themselves and others in their group before the presentation day. They rate each other on a range of factors, including contribution to the group, attendance, collaborative work ethic and compassionate approach. Ratings are on a scale of 0 – 3, with 0 being no contribution at all and 3 being better than the rest of the group. An algorithm is applied, resulting in a factor by which the group mark may be altered to determine an individual mark for the assignment. There are strict guidelines we use to lowering a student's mark for the Group Presentation. The terminology of our Peer Review is deliberate to engender a fair response from group members. What we have learned is that students show great compassion for each other, and when asked about reasons for poor ratings they show great empathy.

3. Discussion of findings

Interdisciplinary collaboration is increasingly recognized as essential in preparing built environment graduates for the complexities of professional practice. However, despite this recognition, interdisciplinary teaching remains relatively uncommon at undergraduate level in UK built environment education. Most examples —such as the University of Cambridge’s Interdisciplinary Design for the Built Environment (IDBE) and the University of York’s Interdisciplinary Modules (YIMs)— are either postgraduate or elective in nature.

In contrast, the Collaborative Practice module at the University of the West of England (UWE) is a core, credit-bearing undergraduate module that explicitly fosters interdisciplinary learning. Delivered at Level 6, it brings together students from architecture, planning, surveying, and construction management to simulate real-world development processes. Students adopt professional roles aligned with their future careers and engage in collaborative decision-making across financial, socio-economic, political, industrial, and environmental dimensions.

This structured approach is distinctive in several ways:

· It embeds interdisciplinary practice within the core curriculum, rather than offering it as an optional or extra-curricular experience.

· It emphasizes professional identity formation, with students working in roles reflective of their future careers.

· It reinforces communication and interpersonal development through specific, targeted lectures and weekly workshops.

· It promotes professional habits such as timekeeping, punctuality, and accountability within group work.

Student feedback collected through UWE’s module and course surveys indicates that learners value the opportunity to work across disciplines and simulate professional roles. Many report increased confidence in communication, a better understanding of other professions, and a stronger sense of preparedness for industry collaboration. These outcomes align with the module’s educational aims and reinforce its effectiveness in fostering real-world skills. External Examiners provide consistently positive feedback saying, “A real strength of the provision is the Collaborative Practice module…, it is a credit to the teaching team that this module has gone from strength to strength. The Blackboard site is excellent providing students with clear week to week guidance and teaching materials. This module will make a significant impact on breaking down barriers between the professional disciplines and enhancing employability.”

The module’s interdisciplinary and collaborative focus aligns with expectations from key professional bodies. RIBA, CIOB, RTPI, and others have jointly committed to improving standards across the built environment professions, including through enhanced equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) and collaborative practice (RIBA, 2022) (RTPI 2025). These bodies emphasize the importance of preparing graduates for multi-disciplinary teamwork, stakeholder engagement, and inclusive design —core elements of UWE’s module.

Recent literature supports the need for such modules. Jeddere-Fisher et al. (2025) argue that addressing sustainability and climate resilience in the built environment requires holistic, interdisciplinary learning experiences that reflect real-world complexity. They highlight the importance of engaging with multiple perspectives and stakeholder viewpoints to inform balanced decision-making—an approach mirrored in UWE’s module design.

In the context of the Collaborative Practice module at UWE, reflective writing helps students:

· Articulate their professional identity by examining their role within interdisciplinary teams.

· Evaluate group dynamics, communication strategies, and decision-making processes.

· Recognize the value of other disciplines, fostering empathy and collaborative skills.

· Develop metacognitive awareness, which supports lifelong learning and adaptability.

In reflecting on UWE’s position, it becomes clear that Collaborative Practice offers a rare and exemplary model of undergraduate interdisciplinary education in the built environment. It not only aligns with national and global calls for collaborative learning but also demonstrates how such pedagogy can be effectively embedded in professional preparation.

4. Conclusion

Collaborative Practice is a flagship module in our built environment school. It is unique in giving students a taste of what working in the industry will be like when working with multi-disciplinary teams. It affords students a greater understanding of the subject material in making something abstract more tangible, e.g. procurement. It requires students to use prior knowledge from other modules to apply to specific tasks for this module, which consolidates learning attained from across their degree to date. It reinforces learning through peer-to-peer learning with students teaching each other about topics from own discipline-specific approach. It provides an introduction to working in industry and allows students to practice their own discipline role in preparation for industry.

We have learned that the benefits of the module extend beyond subject learning. There are many gains for students on a personal level in developing their inter- and intra-personal skills. Students report an increase in confidence in interacting with new people and other disciplines. They learn positive aspects of group work that will make them valuable team members after graduation. Sisti & Robledo (2021) and Wang (2025) discuss how interdisciplinary collaboration and student-led approaches enhance interpersonal skills and confidence, which aligns with the outcomes reported by our students.

This is a complex module with many enmeshed parts. Each aspect contributes to the holistic outcome in which students acquire good collaboration skills and develop empathy and compassion for others on the module. It is a module that prepares students well for practice.

5. References

ARB. 2023. Tomorrow’s Architects: Competency Outcomes for Architects. ARB.

ARB. 2025. The Architects Code: Standards of Professional Conduct and Practice. ARB.

Colvin, Wendy, Abhinesh Prabhakaran, and Michael Roberts. 2024. “Exploring the Relationship Between Confidence and Self-Efficacy in Undergraduate Built Environment Students: A Mixed-Methods Approach.”

Cooper, Emma, Sonia Oliveira, and Dragan Mumovic. 2023. “Advancing Transdisciplinary Architecture and Engineering Education: Defining the Needs of a New Multidisciplinary Built Environment Design Professional.” REHVA Journal 03/2023: 33–39. https://www.rehva.eu/rehva-journal/chapter/advancing-transdisciplinary-architecture-and-engineering-education-defining-the-needs-of-a-new-multidisciplinary-built-environment-design-professional

Eclipse Research Consultants, Cambridge, and Department of Architecture, University of Cambridge. 2004. Effective Teamwork: A Best Practice Guide for the Construction Industry. Constructing Excellence.

Egan, John. 1998. Rethinking Construction: The Report of the Construction Task Force. HMSO.

Gibbs, Graham. 1988. Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic.

HM Government. 2013. Construction 2025: Industrial Strategy for Construction. HMSO.

Jeddere-Fisher, Fiona, Danielle Sinnett, Wendy Colvin, Grazyna Wiejak-Roy, and Danny Elvidge. 2025. “Interdisciplinary Sustainability Curriculum: Case Studies from Undergraduate and Masters Built Environment Modules.” In Embedding Sustainability in Built Environment Curricula: Opportunities and Challenges, 171–190. Springer.

Kolb, David A. 2015. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. 2nd ed. Pearson Education.

Latham, Michael. 1994. Constructing the Team: Final Report. HMSO.

McCarthy, John. 2011. “Reflective Writing, Higher Education and Professional Practice.” Journal for Education in the Built Environment 6 (1): 29–43. https://doi.org/10.11120/jebe.2011.06010029

Moon, Jennifer A. 2004. A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning: Theory and Practice. Routledge.

RIBA. 2022. “Built Environment Bodies Commit to Three-Year Action Plan to Improve Equity, Diversity and Inclusion.” https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/knowledge-landing-page/built-environment-bodies-unite-to-improve-inclusion-and-diversity

RTPI. 2025. “Built Environment Professional Bodies Deepen Commitment to EDI with Two New Signatories.” https://www.rtpi.org.uk/news/2025/june/built-environment-professional-bodies-deepen-commitment-to-edi-with-two-new-signatories/

Schön, Donald A. 1992. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Routledge.

Sisti, Mary K., and Jodi A. Robledo. 2021. “Interdisciplinary Collaboration Practices between Education Specialists and Related Service Providers.” The Journal of Special Education Apprenticeship 10 (1). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1302874.pdf

Wang, Li-Qiong. 2025. “Collaborative, Interdisciplinary, and Student-Led Approaches in Education.” Athens Journal of Education 2025: 12:1–18. https://www.athensjournals.gr/education/2024-6135-AJE-EDU-Wang-03.pdf

Short CV

Wendy Colvin leads interdisciplinary and collaborative teaching of professional studies. At UWE, she is the Part 3 Programme Leader, one of the largest courses outside London. She leads the undergraduate module, Collaborative Practice, required as part of eleven award disciplines (approximately 300 students) and is supported by a multi-disciplinary tutor team of eighteen colleagues and Guest Speakers from industry representing key employers. She undertakes external roles that help shape architectural education and the profession both in the UK and internationally. Currently, she is Chair of the Association of Professional Studies in Architecture (APSA), whose aim is to improve provision and collaboration of professional studies and training in schools of architecture and professional practice. This involves working closely with professional bodies, including ARB and RIBA.