Strategies of care in architectural education for future practice / Estrategias de cuidado en la enseñanza de la arquitectura para la práctica futura / Estratégias de cuidado na educação arquitetônica para a prática futura

Felix, Sandra1; Stone-Johnson, Brigitta2; Szentesi, Anita3; Bahmann, Dirk4

1. University of the Witwatersrand, School of Architecture and Planning, Department of Architecture, Johannesburg, South Africa, sandra.felix@wits.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7401-0234

2. University of the Witwatersrand, School of Architecture and Planning, Department of Architecture, Johannesburg, South Africa, brigitta.stone@wits.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1044-310X

3. University of the Witwatersrand, School of Architecture and Planning, Department of Architecture, Johannesburg, South Africa, anita.szentesi@wits.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7807-1293

4. University of the Witwatersrand, School of Architecture and Planning, Department of Architecture, Johannesburg, South Africa, dirk.bahmann@wits.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9404-9080

Received: 29/05/2025

Approved: 13/09/2025

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/astragalo.2025.i39.07

Abstract

This paper considers pedagogical strategies of care across the undergraduate curriculum, within the School of Architecture and Planning (SoAP) at the University of the Witwatersrand. Developed in response to South Africa’s colonial and Apartheid legacies, as well as the more recent calls for a more decolonised education within the #FeesMustFall Movement. The paper presents three case studies that propose strategies to counter colonialism within the South African architectural system, which has historically privileged Western epistemologies and marginalised indigenous knowledge and embodied ways of knowing. This has led to the training of students to be industry-ready rather than practice-ready professionals, thereby reinforcing extractive modes of practice. In contrast, this paper foregrounds care as a critical and decolonial practice in architectural education that fosters practice readiness. This paper explores pedagogical strategies of care across the undergraduate degree. In the first year, Character-Led Design cultivates empathy and social consciousness through narrative and storytelling, by reflecting on Johannesburg’s mining history and colonial settler beginnings. Through embodied making in the second year, students enter into correspondence with material agency and atmospheric qualities, generating tacit knowledge that deepens their awareness of human and more-than-human interrelations In the third year, personal spatial narratives unearth tacit design knowledge from lived experience, enabling students to situate themselves critically within institutional and professional frameworks. These approaches scaffold students’ development of self-awareness, empathy, and critical agency, equipping them to challenge extractive norms as they go into practice. We argue that care in architectural pedagogy is not merely pastoral but an epistemic and ontological stance that validates relational, embodied, and affective knowledge. Such strategies of micro-resistance counter entrenched colonial paradigms, foster inclusivity, and prepare graduates to practice architecture in ways attentive to social justice, ecological interdependence, and pluriversal worldviews transforming both the profession and its pedagogies from within.

Key words: care, architectural education, design pedagogy, practice-ready

Resumen

Este artículo considera las estrategias pedagógicas del cuidado a lo largo del plan de estudios de grado, dentro de la Escuela de Arquitectura y Planificación (SoAP) de la Universidad de Witwatersrand. Se desarrolla en respuesta a los legados coloniales y del Apartheid en Sudáfrica, así como a las demandas más recientes hacia una educación más descolonizada dentro del movimiento #FeesMustFall. El artículo presenta tres estudios de caso que proponen estrategias para contrarrestar el colonialismo dentro del sistema arquitectónico sudafricano, que históricamente ha privilegiado epistemologías occidentales y marginado los saberes indígenas y las formas encarnadas de conocimiento. Esto ha conducido a la formación de estudiantes para estar preparados para responder a las demandas del sector más que para la práctica profesional, reforzando así modos extractivos de ejercer la arquitectura. En contraste, este artículo coloca el cuidado como una práctica crítica y descolonial en la educación arquitectónica que fomenta la preparación para la práctica. Este trabajo explora estrategias pedagógicas del cuidado a lo largo de los estudios de grado. En primer año, el diseño guiado por personajes cultiva la empatía y la conciencia social a través de la narración de historias, reflexionando sobre el pasado minero de Johannesburgo y los inicios coloniales. En segundo año, las prácticas materiales encarnadas sitúan a los estudiantes dentro de los entrelazamientos del mundo humano y más-que-humano, fomentando la sensibilidad hacia las atmósferas y la materia a través de la práctica encarnada. En tercer año, las narrativas espaciales personales desentierran un conocimiento tácito de diseño a partir de la experiencia vivida, permitiendo a los estudiantes situarse críticamente dentro de marcos institucionales y profesionales. Estos enfoques estructuran el desarrollo de la autoconciencia, la empatía y la agencia crítica de los estudiantes como futuros profesionales, equipándolos para desafiar las normas extractivas al ingresar en la práctica. Sostenemos que el cuidado en la pedagogía arquitectónica no es meramente de acompañamiento, sino una postura epistémica y ontológica que valida los saberes relacionales, encarnados y afectivos. Tales estrategias de micro-resistencia contrarrestan paradigmas coloniales arraigados, fomentan la inclusión y preparan a los graduados para ejercer la arquitectura de manera comprometida con la justicia social, la interdependencia ecológica y las cosmovisiones pluriversales, transformando tanto la profesión como sus pedagogías desde dentro.

Palabras clave: cuidado, educación en arquitectura, pedagogía de diseño, capacitado para la práctica profesional

Resumo

Este artigo considera estratégias pedagógicas de cuidado ao longo do currículo de licenciatura na Escola de Arquitetura e Planeamento (SoAP) da Universidade da Witwatersrand (Wits). Estas estratégias foram desenvolvidas em resposta ao património colonial e do Apartheid na África do Sul, bem como aos apelos mais recentes por uma educação descolonizada no âmbito do movimento #FeesMustFall. O artigo apresenta três estudos de caso que propõem estratégias para contrariar o colonialismo no sistema de ensino de arquitetura Sul-Africano, que historicamente privilegiou epistemologias ocidentais e marginalizou conhecimentos indígenas e modos de saber incorporados. Tal contexto levou à formação de estudantes preparados para a indústria, mas não para a prática, reforçando assim modos de prática extrativos. Em contraste, este artigo coloca o cuidado em primeiro plano, enquanto prática crítica e descolonial no ensino da arquitetura que promove a prontidão para a prática. Exploram-se estratégias pedagógicas de cuidado ao longo da licenciatura. No primeiro ano, o Character-Led Design cultiva empatia e consciência social através da narrativa e da prática de contar histórias, refletindo sobre a história mineira de Joanesburgo e os primórdios coloniais. No segundo ano, práticas materiais incorporadas situam os estudantes entre o mundo humano e o mais-que-humano, promovendo sensibilidade às atmosferas e à matéria através da prática incorporada. No terceiro ano, narrativas espaciais pessoais desenterram conhecimento tácito de design a partir da experiência vivida, permitindo aos estudantes situarem-se criticamente nos quadros institucionais e profissionais. Estas abordagens estruturam o desenvolvimento da autoconsciência, da empatia e da agência crítica dos estudantes, equipando-os como futuros profissionais capazes de desafiar normas extrativas. Argumentamos que o cuidado no ensino da arquitetura não é apenas pastoral, mas uma posição epistémica e ontológica que valida o conhecimento relacional, incorporado e afetivo. Tais estratégias de micro-resistência contestam paradigmas coloniais enraizados, promovem inclusão e preparam os diplomados para praticar arquitetura de forma atenta à justiça social, à interdependência ecológica e a visões pluriversais, transformando simultaneamente a profissão e as suas pedagogias a partir de dentro.

Palavras-chave: cuidado; educação arquitetonica; pedagogia de design; preparado para a prática profissional

Practice-ready versus industry-ready

Owing to the legacy of South Africa, founded as a European colony, and its history as a mineral and material resource for Western wealth, we see the real frictions that architectural practice and education must address. The legacy of ongoing material extraction, utopian construction, abandonment, ruin, and new utopian imaginings is both driven by the colonialism of the past and the capitalism of the present—two sides of the extractive project, metered out on the bodies and minds of the country and its peoples.

During apartheid, within the university education context, the knowledge project became divided between knowledge deemed appropriate for formally white universities and vocational training techniques in former black universities. Further, the knowledge projects in both types of universities excluded expertise considered unworthy of study due to its origins in African indigenous cultures. The field of architecture was exclusively taught in the white university system, and the knowledge they taught excluded local indigenous housing and spatial practices. Under this system, with a few exceptions, African students were limited to post-school vocational training, teacher training or night schools, relegating African people to the working class and unskilled labouring professions (Abdi 2003). Largely tacit and embodied ways of knowing and thinking about the built environment were excluded from the university knowledge system, which tends to favour knowledge of the mind over embodied knowledge (Pallasmaa 2009, 11).

Practice-ready and industry-ready are two very different concepts. The term ‘Industry-ready’ panders to the requirements of the industry and profession, which are highly skewed to digital technologies and technical skills, often overlooking broader ontological and epistemological concerns within spatial practice. The term Practice-ready, as seen by the cohort of undergraduate educators in this paper, is a broader concept which includes technical and digital skills but also, perhaps more importantly, self-awareness, situatedness and confidence to engage with the profession and contribute to its transformation.

For architecture, the need to produce industry-ready architectural graduates has perpetuated the Western knowledge model. Today, students are increasingly trained to work in existing offices and operate software rather than open new firms or explore new approaches to spatial or material practice. As a result, far more consideration is given to ensuring students are industry-ready and employable, with almost no attention given to whether practice is ready for our students or whether our students are practice-ready

The adoption of Modernism and Bauhaus-style teaching methodologies during the rise of Apartheid in South Africa, in which the students are seen as an empty vessel to be filled with knowledge, relying on any prior knowledge to be erased, led to little exploration of critical regionalism, materiality, or critical engagement with Indigenous building construction. This, however, briefly changed during the period from 1975-1990, when Amancio’ Pancho’ Guedes's tenure as head of the department at the School of Architecture and Planning (SoAP) at the University of the Witwatersrand, brought a unique blend of African, European and global avant-garde ideas and a shift in focus towards arts and crafts, more socially engaged architectural approaches (Le Roux 2022, 86). Post 1994, the focus again shifted from materials and objects to narratives of activism and explorations of planning to redress Apartheid spatial disparities. (Le Roux 2022, 86) During the mid to late 2000s, many pedagogical approaches became geared toward producing industry-ready professionals due to pressures placed on academia by industry.

Nearly thirty years Post-Apartheid, and one hundred years post-colonialism, the experience of African students within formally white universities remains alienating (Bazana and Mogotsi 2017). Jansen (2019) suggest that the knowledge project has been principally untransformed since the end of Apartheid. Within the broader higher education context of South Africa, systemic transformation during the post-Apartheid era has been slow, inevitably leading to the #FeesMustFall movement in 2015. The student protests, focusing primarily on formerly white educational institutions, called for decolonised education and demanded free higher education.

Within Schools of architecture, students are primarily expected to conform to the minority culture, with their own cultures and contexts often deprioritised. They are treated as malleable material to be enculturated, often through pedagogies that erase their tacit spatial experiences and understanding. Consequently, graduates become entrenched in these world views and perpetuate the status quo of institutional epistemes into professional practice, failing to contest or transform established norms. While significant strides have been made since the end of Apartheid, at Wits, institutional transformation is slow, continuing to operate through and perpetuating colonial paradigms.

A Return to Tacit and Embodied Knowledge, as a response to #FeesMustFall’s call for decolonised education

In response to the #FeesMustFall protests (2015 to 2019), within Wits SoAP, we are experimenting with and developing a pedagogy that seeks to address the complexity of the Post-Colonial / Post-Apartheid knowledge system, which we feel remains entrenched in an extractive understanding of place and matter.

This process has included deep personal reflections on the researchers' entanglements and the effect of extractivist mindsets on our personal experience. We concluded that, as educators within a professional architectural degree program in Johannesburg, we are inevitably entangled within these extractive regimes. Both through practice and the educational framework in which we operate. Yet we each, in our way, felt the need to reconcile our tacit understandings of the world with the training we had received.

However, to achieve systemic change, we believe architectural pedagogy must strive to create real, emotive experiences that expand awareness beyond the legacies that have shaped our beings. The goal is to shift modes of being to recognise and embrace alternative alignments that prioritise care, harmony, equity, and respect for human, non-human, and more-than-human relationships. These alignments should encompass multiple worldviews, beings, and realities rather than confine themselves to strict, narrow ideologies. At SoAP, Wits, we believe that architecture and urban planning are equally important in informal townships as in the monuments of power, and we should learn from all aspects of South Africa's built fabric.

The Tacit, Dimension Polanyi suggests, requires knowing more than we can say (Polanyi 1966, 4). To use Pallasmaa’s way of thinking, knowledge comes from the mind, the body, and the body's encounter with the materials and atmospheres of the world (Pallasmaa 2009). We extend this to architectural education, which we suggest should encourage encounters with the material world, and reflection upon a student's tacit knowledge and learnt cultural heritage, to enable the development of new, culturally embedded knowledge through their journey towards practice-readiness. To build their own body of knowledge, practitioners and students must create something that is appropriate not only to the context but also to their lived experience. In this way, the post-colonial knowledge project can be considered ever-evolving, a living knowledge body.

In addition, one of the core values that has emerged within the school in recent years in response to this personal entanglement with knowledge is the ethics of care as redress for extractive attitudes towards people, matter, and land.

Pedagogies of care supporting practice-readiness:

The pedagogical approach to teaching in the following sections aims to support students' conscious development and critical agency, beginning to challenge extractive labour culture, and cultivate various aspects of tacit knowledge, empathy, material engagement, and lived experience, while preparing for practice-readiness and contributing to the transformation of the South African profession. Through a process of conscious becoming, the development of critical agency, careful practice and response-ability (Haraway 2016) is scaffolded from first to third year in. This paper examines the strategies that enhance students’ practice-readiness, encompassing both cognitive and affective aspects, and counters the extractive nature of the architectural profession.

Through asking questions, such as: How do we respond to a world in crisis? What do we do, and why do we do it? Students' worldviews are expanded and, at times, contested by making visible the co-existence of alternative paradigms and diverse worldviews within the studio. This is done through different social and material strategies underpinned by a pedagogy of care.

Care is …“a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue and repair our 'world' so that we can live in it as well as possible. The world includes our bodies, ourselves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web” (Tronto and Fisher 1990, 40)

In architectural pedagogy, we extend Tronto and Fisher's four phases of care: caring about, caring for, caregiving, and care-receiving (Tronto and Fisher 1990; Tronto 1998) into the notion of an ecosystem of care. This ecosystem of care demonstrates that you cannot teach care without caring for students, who, through receiving care, can then care for themselves and their practice and only then, by extension, care for others, for the environment, the city and the life-sustaining web that is our world. This ecosystem of care in architectural pedagogy understands "the interdependence of the economy, ecology, labour and future repair" (Krasny and Fitz 2019, 16).

Care in architectural pedagogy can also be seen as a radical decolonial practice, especially in the context of a post-colonial, post-Apartheid and post #FeesMustFall university. The school aims to develop within the student body a core value of care towards each other, society, the environment, the city, and the material world within which we are all entangled. The idea of 'care' places a series of critical pedagogic concerns under a single umbrella, including the need to reframe human and matter relations within sustainable design approaches. Considering the shifting social and well-being considerations within architectural practice, the changing landscape of the profession's role and place in the South African context, and climate concerns. It also calls for a critical re-assessment of decolonial thinking within the profession.

Care mustn't be understood purely as a pastoral concern or a form of emotional support. Such an interpretation risks separating care from the epistemic and ontological grounds of design. In our framing, the affective dimension is foundational. Without affective engagement, care becomes discursive positioning devoid of personal and emotive commitment and thus disconnected from the embodied and situated nature of the practices explored here. The pre-cognitive, embodied resonance between people, places, materials, and histories anchors care in a felt connection with the world, and it is here that care becomes operational rather than rhetorical.

This affective engagement is inseparable from tacit knowledge (Polanyi 1966; Schön 1984). To cultivate care in architectural education, it is therefore crucial to cultivate students’ capacity to sense, respond to, and be moved by the complexities of the human and more-than-human worlds they design within. Such a position resists the traditional institutional and academic bias towards privileging intellectual knowing over embodied, emotional, and sensory forms of knowing. This bias has historically produced architects trained to analyse and represent, but not necessarily to attune and correspond (Ingold 2013) with the realities they encounter. By reinstating the affective as a legitimate and necessary mode of knowledge production, we advocate for an architectural education in which practice-readiness is inseparable from the capacity to feel and to care — not sentimentally, but as a rigorous, critical, and ontological orientation.

Practice informs pedagogy

We are all architects/artists, educators and researchers, and our diverse practices inform our pedagogy.

Responding to an unease with the erasure of her embodied way of knowing, the world, and a disjunction in her understanding of how she perceived the more-than-human at odd with her education. Dr. Brigitta Stone-Johnson's research, creative practice, and teaching respond to questions of material inertness and empty land thinking within the post-extractive urban landscapes of Johannesburg. By creating awareness of material agencies within post-extractive terrains through artistic, creative practice and explorations of Stoney vitalities within the highveld context, drawing on the feminist, posthuman work of Jane Bennett (2010), Donna Haraway (2016), Rosi Braidotti (2013), and Stacy Alaimo (2018), among others, who call for working in, with and through the more-than-human agencies of the material world. She rethinks the vitality of post-extractive terrains as lively and agentic co-labours with human agents in creating the city of Johannesburg, aiming to counter-narrate extractive attitudes. Her work, research, and teaching methods explore the body as a critical vehicle for knowing and becoming entangled with material vitalities within the African Anthropocene. Within her teaching practice, this translates as an emphasis on relationality between people, things, and matter. Through her pedagogic approach across a range of subjects, taught alongside those of her colleagues' work presented in this text, including Theory and Practice of Construction, Building Ecology and Introduction to Structures. She aims to foster an understanding of the vitality of materials used to make our cities by promoting in-depth material research and hands-on experience with geologic systems in the design and construction of buildings. Within her approach, she seeks to give room for the development of the students by giving them room to explore a line of inquiry based on their personal interest, temperament, and cultural aesthetics, framed by material engagement and exploration of making through the process in embedded contexts.

Character-Led Design is a practice of care created by architect and filmmaker Anita Szentesi, which integrates architecture and film to create inclusive learning environments and encourages students to consider life's complexities in their designs. Szentesi’s experience in commercial architectural practice revealed that buildings are often designed based on pragmatic, functional and capital values only, treating occupants and context as abstract entities in the design process. She feels that this approach neglects emotional and sensory experiences, as well as the unique characteristics of places and their inhabitants. This detachment motivated her to pursue a more thoughtful approach to architectural design and pedagogy. The Character-Led Design approach focuses on designing spaces from a character's lived experience, using the filmic narrative of screenwriting. Starting with a film script involves imagining how characters develop in the places they inhabit and spaces wherein their emotional journeys unfold. By sharing stories, which also involves listening to them, the objective is to shift from a traditional top-down design approach to a more inclusive, bottom-up approach. This technique, which is not typical in traditional architectural design processes, seeks to transform how architects are taught and subsequently practice.

Dirk Bahmann is an artist-researcher whose practice centres on the tacit domains of material and atmospheric dimensions of making, engaging the quasi-thing domain of architectural atmospheres. His work integrates sculptural making with psychotropic practices creating conditions for heightened perceptual attunement and the unlearning of inherited Western settler ontologies. This embodied, situated mode of inquiry has for him re-formed vital relationships with the thingness of the world, revealing alternative ontological alignments grounded in lived experience. The insights emerging from these practices inform and guide pedagogical strategies that attempt to bring into conversation the intelligences of body, material, and place with design practice and creativity. In turn, observing students’ process, articulations, negotiations and coming to terms with material, atmosphere, and contexts re-informs his own practice, offering renewed perspectives on tacit and embodied ways of knowing

As an architect-researcher, Sandra Felix gained critical and conscious self-awareness of the roots of her design practice, shifting and transforming that practice through practice-based design research. As an educator, she adapted these practice-based design research methods to undergraduate pedagogy. This approach similarly made students' design practice more conscious, critical, and careful, as well as more confident in integrating into a transforming architectural industry, as confirmed by focus group discussions. Her autoethnographic practice-based design research, and the impact it had on her own practice was replicated in the impact that this type of research has had and is still having on students’ design practice. In doing so she became not only a “reflective practitioner”(Schon 1984) but also a “critically reflective teacher”(Brookfield 2017), expanding the relevance of autobiography beyond that of the teacher’s “autobiography as a learner”(Brookfield 2017, 161) to include students’ autobiographies as generative for their own learning.

Journeying into a shared enquiry

The four colleagues in conversation within this paper share some common ground. We are all graduates of the Wits School of Architecture and Planning, although at different times in its history. We have all practised architecture in Johannesburg. We all live and work within Johannesburg. We have all returned here and have done so for an extended period. Three of us are doctoral students, part of the same cohort, whilst one is post-doctoral; a different three shared a creative workspace a few years ago. Some of us come from Johannesburg and love studying architecture. One of us is neurodiverse, and comes from a rural area, and has never felt comfortable in the school or the academic space. Another felt disillusioned with the commercial side of architecture after a decade of practice. We are colleagues in conversation, each having undertaken our journey to arrive at a place of common enquiry, around these questions of tacit knowledge, ethics of care.

In the following sections, we examine the practices undertaken by educators, researchers, and practitioners in response to the development of practice and industry readiness in a world of multiple overlapping crises and a locally transforming profession, focusing on care through varied pedagogic approaches. We begin with the admission process strategies, which are key to transforming access to the university. The care demonstrated at admissions underpins the care in the first year of study and proceeds sequentially through the undergraduate program.

In seeking to create a way to broaden access to the university space, that breaks down the systemic barriers placed on the institution, by the intergenerational legacy of rationalised education, as discussed in the introduction. The SoAP admissions process has been created as a system of exercises for applicants which tests not only academic merit, but also tacit skills, of making, wayfaring, storytelling, and imagining alongside the kinds of drawing and drafting skills a prospective architectural student might need. In creative writing, applicants are encouraged to use narrative writing, to imagine alternatives to the world they inhabit. Outside of the narrative text, applicants are tasked with designing and making an object that is meaningful to the creation myth of the imagined world. Here, we draw on Polanyi's suggestion that knowing begins with reflection on embodied experience. (Polanyi and Sen 2009a, 16). By encouraging applicants to reflect on their world, we hope to facilitate the start of the journey to knowing. For students from previously disadvantaged communities, this aims to create a sense that the school is open to applicants from all backgrounds, and that each person's spatial memory is welcome within the school. Each student who meets the initial exercise criteria is then interviewed by staff within the school. The aim is to understand who they are as individuals, connect with applicants on a personal level. This sense of personal connection becomes the soil upon which we hope to build the next generation of architectural practitioners. As a result of these measures, our student body is now more reflective of the multicultural dynamics of the city we find ourselves in, as they can be evaluated on aptitudes outside of academic skills alone.

All students in the SoAP undergraduate program, during the years incorporated in this study (2018-2024) completed the first and third year architectural design studio described, however the second-year material cultures studio is a smaller elective studio chosen by 25-30% of the second-year cohort.

Planting the Seeds for Inclusive Practice Through Narrative in First-Year Architectural Design Pedagogy

The initial project first-year students are introduced to in the architectural design studio is AlterNative Jozi, which centres on Character-Led Design inspired by the character-driven narrative from screenwriting which engages audiences by allowing them to form emotional connections with the evolving characters (Field 2005, 22). A film script brings conflict and climax to the architectural design process, serving as an 'entertainment narrative' for designers (Grimaldi et al. 2013). It encourages the exploration of empathy, identification, and memory through personal stories, aiming to integrate others' connections to history, identity, and place in the design process. The concept of Character-Led Design suggests that architectural practices informed by the perspectives of characters can generate emotional investment and cultivate a sense of care and ownership among designers. Character-Led Design evokes empathy in the designer, by allowing individuals to "dwell in" another person's perspective, aligning with the concept of indwelling from tacit knowledge knowledge (Polanyi and Sen 2009, 11 ) Character-Led Design also resonates with Thomas Avermaete's ‘Death of the Author, Centre and Meta-Theory’ (Hein 2017, 481), which addresses the multidimensionality of urban experience histories, suggesting that explorations of challenging and less familiar sources and methods should be explored, including film. Employing this technique addresses decolonisation within this University's context, countering top-down design approaches rooted in extractive colonial history. It tackles the enduring centre-periphery divide, where "First World" cities are seen to generate theory and policy, whilst "Third World" cities are seen as problematic and in need of reform (Hein 2017, 481).

The title, AlterNative Jozi, is layered to encourage reflection on the context in which the class is situated. ‘Alternative’ refers to something that challenges traditional norms, suggesting different ways of being and implies that diverse paradigms exist beyond a singular universal perspective, aligning with Walter Mignolo's concept of the pluriverse (Reiter 2018, x). Pluriversality rejects the notion that the world must be seen as a unified whole and instead views it as an interconnected diversity. Alternative also suggests other ways of knowing, highlighting the centre-periphery issue, which Jansen (2019, 62) argues is more likely the problem with knowledge production in South African higher education rather than decolonisation.

‘Native’, the second part of the compound word alternative, means indigenous to Johannesburg, aiming to provoke thought about the value of Indigenous knowledge and its systems rather than only aspiring towards Western or global ideals. In this project, the concept of characters and storytelling align with the indigenous research approach to storytelling (Smith 2012, 145). As a research tool, storytelling is a useful and culturally appropriate way to represent diversities of truth, allowing the storyteller, rather than the researcher, to maintain control. Stories are inherently tied to knowledge, serving as both method and meaning. ‘Jozi’ is a slang abbreviation for Johannesburg.

|

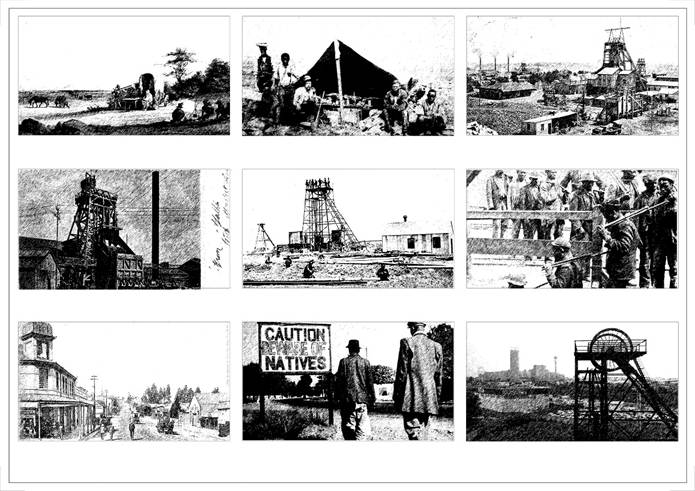

The AlterNative Jozi Project is divided into briefs that outline specific processes students must follow to achieve their design goals, ensuring that they engage with the Character-Led Design practice of care from the outset. The steps in the brief guide students to navigate their narrative and design process. Students imagine stories that take place across the past, present, and future of two contrasting worlds in Johannesburg, featuring opposing characters, the protagonist and antagonist, who will inhabit those worlds. The brief’s second stage is the design phase, where the architectural concept, form, function, and spatial planning are developed based on the narrative. The third stage educates students about architectural drawing and orthographic projections, and the final step involves students presenting their portal through architectural drawings that reflect the narrative. The students are provided with a visual storyboard of Johannesburg’s history to help them begin their narrative (Figure 1). The storyboard features thought-provoking images: colonial settlers arriving in the Johannesburg Highveld in their ox wagon; the settlers' interaction with native Africans; the development of gold mining; the construction of mining equipment, and the growth of mining towns that eventually become Johannesburg. As the city develops, native African men are employed for hard mining labour, creating a dichotomy between the land and the body, both of which are exploited for extracting capital resources. The eighth storyboard frame evokes strong emotions by depicting the backs of the native African men walking past a large signboard that states “Caution Beware of Natives”. This frame depicts the social injustices that took place during Apartheid. The storyboard concludes with an image of modern-day Johannesburg, allowing the viewer to imagine their own alternative story in response to what they have seen.

Fig. 1. AlterNative Jozi, Storyboard of Johannesburg’s history by Author. 2022.

Students respond by creating a personal story, their visual narrative in a second storyboard. They contribute their unique perspectives, challenging the given storyboard by addressing a current issue in Johannesburg that they relate to and believe they can resolve through designing their alternative portal. Their characters inhabit both worlds of the story, embodying complex beings who possess insight into Johannesburg’s extractive past while grappling with the current issues the student has identified in the city. The characters and the narrative are vessels that the students inhabit; the narrative enables a deep understanding of the site and context, and the characters, a deep empathy for those living and embodying the narrative or context. These character and narrative vessels of embodiment align with indwelling (Polanyi and Sen , 11), enabling designers and students to engage with culturally and sensorially situated ways of knowing. They pay close attention to subtle cues from lived experiences, leading to a comprehensive understanding of another’s world. Character-Led Design directly employs this process. Students imaginatively immerse themselves in their characters, internalising their sensory and emotional experiences. This approach fosters an architecture of care, where spatial choices arise from a deep, embodied, and empathetic connection to the lives that the spaces are intended to serve, rather than from an abstract formal perspective. Students become active creators of knowledge rather than relying solely on traditional top-down teaching methods, where the educator directs students. This student-led approach turns the brief into a collaborative effort with educators.

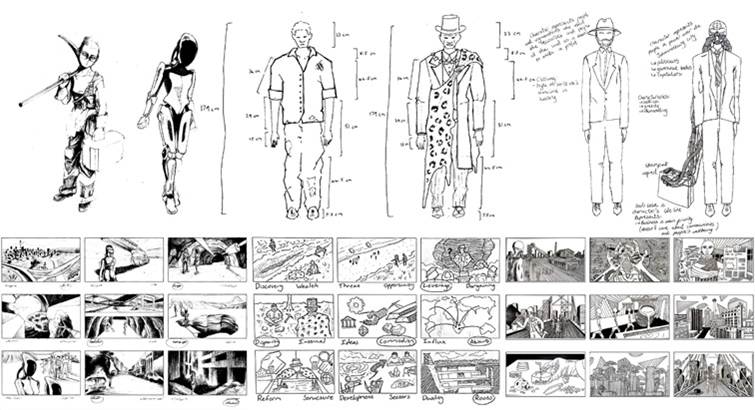

Fig. 2. AlterNative Jozi Varied Output of Characters and Storyboards by SoAP Students 2022.

The characters,

narrative, and worlds created by students in the second storyboard depict multiple

perspectives of Johannesburg., The diverse characters who embody Johannesburg, represent

the viewpoints of the students who have made them. This selection of characters

and stories by various students (Figure 2) responds to the same brief. Still,

it includes different themes: gender equality, technology in mining, wealth

inequality, and a world where the environment is valued and not treated

as a commodity for capital gain. All these narratives and characters challenge

what an alternative world could be like if colonisers and native Africans had a

different history with one another in South Africa. Multiple viewpoints

are created, shared, and heard, an approach that focuses on inserting diverse

points of view, previously excluded, into the institution's historical archive.

Multiple alternative future paradigms are envisioned, which counter the

universal hegemonic view inherited from the extractive colonial past.

The storyboards connect directly to architectural conceptual sketching and orthographic projections. Through this combined film and architectural visual language, the students' imaginations about their narratives and characters begin to develop as real possibilities for an architectural translation within a specific context. The storyboards inspire concepts, visualise the yet-to-be-designed building with specific users in a context, and perceive the design over time, historically, presently, and in the future. The ideas in the storyboard are transformed into spatial translations and spatial experiences. The narrative as a design driver is iterative and guides the design process continuously.

The architectural design process also affects the narrative. As spatial experiences are translated into architectural forms, the storyboards are revised to include these designs. In this way, the design shapes the narrative and the characters, encouraging students to reflect on and refine both the design and the narrative as the process unfolds. The design results in an architectural pavilion (Figure 3) that combines present Johannesburg with a contrasting imagined alternative Jozi designed through a thoughtful, inclusive, collaborative practice of care. Various pavilion designs showcase national issues and specific challenges students aim to tackle based on their lived experiences, providing a well-rounded design perspective. The portal designs (Figure 3) derived from the stories and characters shown in (Figure 2) illustrate the contrasting spaces shaped by the narrative. Two of the portals' stories are based on mining, clearly highlighting the difference between above-ground and below-ground. The third design celebrates a return to a healthier relationship with the environment.

In conclusion, the Character-Led Design technique has transformed how first-year architectural students learn to design spaces, influenced by ambience and meaning, not just dimensions or site constraints. By designing through the stages of a story, from a sentient being who inhabits this specific world, faces a crisis, and is evolving, (Grimaldi et al. 2013) students conceptualise spaces without preconceived notions. These unique spaces stem from intuitive understanding and spatial culture shaped by lived experiences, integrating the spatial atmosphere experienced by the character into the design process.

The Character-Led Design approach aligns with the ongoing shift in global urban planning mindsets from top-down to bottom-up methodologies, such as Action Archive, co-founded by Meike Schalk, Sara Brolund, and Helena Mattsson (Gromark et al. 2018, 30). This organisation positions architects and historians as active participants within a network that facilitates the collection of often unrecorded stories from history, particularly the overlooked voices of marginalised groups, to create an active archive that can inform design practices. The Character-Led Design methodology has the potential to contribute to this global transition toward a bottom-up approach in architectural design and planning.

Because the main aim of architectural pedagogy is to prepare students for architectural practice, Character-Led Design aims to instil empathy and understanding and foster socially conscious (Escobar 2018) practitioners who can reshape the future of architecture, thereby transforming the profession from the ground up. The ability to empathise, as noted by Polanyi and Sen (2009), involves a nuanced process of attuning to the often subtle cues present in a character's environment. This attention helps to foster a deeper understanding of the spatial and cultural context surrounding the character. By internalising these lived or imagined perspectives, students cultivate an implicit knowledge that influences their design decisions with a relational awareness, ultimately enhancing their sensitivity to the experiences of others.

Intersections with non-human worlds- second year

Although embedded within the architectural profession, the academy offers opportunities to enact micro-resistances by fostering spaces that nurture alternative ontologies. A second-year elective that typically accommodates approximately 25 (of 75) students, exemplifies this approach by creating affective, lived experiences through design thinking and making processes that focus on the felt body (Griffero 2016). Griffero describes the felt body as the bodily sphere in which atmospheres are directly sensed and affect us pre-cognitively, shaping our experience before conscious interpretation (Griffero 2016). This reframing shifts attention away from the explicit, articulated world of conventional design practice and positions students within a more nebuleous mode of engagement that cultivates empathy toward the interconnectedness of human and more-than-human worlds

Within this frame, the course embeds tacit knowledge (Polanyi 1966, Schön 1984, Pallasmaa 2009) as a bridge between an ethics of care and practice-readiness. Tacit knowledge, formed through embodied experience, sensory attunement, and situated responsiveness, enables designers to act with situational intelligence, empathy, and sensitivity to place. It emerges through making, where thought unfolds in relation to the felt body, the agency of materials, and the designer’s contextual conditioning. By cultivating this dimension, the course resists the anthropocentric bias of a digitally mediated, consumerist culture, translating care from an abstract value into a deeply internalised ontology that emerges in the design process.

The project begins with students selecting a significant life experience imbued with strong affective content as the foundation for their work. These experiences, chosen for their vivid emotional clarity, anchor an otherwise open-ended brief. Guided by the atmospheric qualities of these memories, students translate them into staged spatial assemblages constructed from Plaster of Paris, and microprocessor-controlled lighting. The aim is to evoke and convey, to an audience, the emotive essence of the experience in a tangible, material, yet atmospheric form (see figure 4).

To do this, students employ embodied methodologies such as gesture, performance, vocalisation, and iterative making. This approach moves design away from the abstraction often produced through traditional drawing methods, engaging instead with the tacit dimension of atmospheric affect. Working with form, texture, materiality, lighting, and figure–ground relationships through direct bodily engagement grounds design in felt experience. In this way, students develop the ability to read, respond to, and shape atmospheres, which is significant within regimes, where the vitality and interdependence of matter are normally overlooked.

The making process, understood as a relationship between body and material, brings students into direct sensory contact with their medium. They observe plaster’s transformation from powder to solid, work with it at different stages of hardness, and note how its behaviour changes over time. In doing so, they begin to understand the “personality” of the material from the inside out, an understanding that develops through trial, adaptation, and response rather than through preconceived theory. This reciprocal engagement decentres human agency, positioning students at the intersection of the human and more-than-human. In this way, the process enacts what Ingold (2013) calls correspondence, a continuous dialogue in which humans and their environment influence and shape one another. It is through the body, Ingold argues, that we come to know and understand the world, an approach that challenges the detached intellectual epistemology by reintroducing the felt and intangible as meaningful components of inquiry.

This sensibility is not a superimposition of the self onto the world, but an alignment with it, within which students encounter the vitality and agency of matter. As Jane Bennett (2010) describes, matter possesses its own liveliness and capacity to influence its surroundings. In working with Plaster of Paris, this vitality is revealed through the material’s resistance to predetermined intentions, especially when students fail to respond to the way it “wants to be” (Kahn and Lobell 2008). For many in a digital generation, such resistance is unfamiliar and striking. Through direct bodily engagement, students learn to recognise plaster’s unpredictable behaviour, its changing characteristics, quirks, and auratic presence. They also see that making is shaped not only by the material itself but by weather, ambient conditions, and their own emotional states. The site of making thus emerges as an assemblage of multiple agents, with the student as one participant among many. This broadened awareness of agency leads to the realisation that design is not authored in isolation but arises in and through relationships.

Karen Barad's (2007)concept of agential realism builds on this relational understanding. Barad proposes that agency is not the result of individual entities' actions, but emerges through intra-actions, the ongoing relationships between entities. From this perspective the boundaries and properties of both the student and the plaster are not pre-given but are dynamically constituted through their entanglement. This challenges the notion of separateness and individualism, and reveals that things emerge from the very relations that bind them. This view reinforces the course’s aim of enabling students to design with, rather than over, the worlds they inhabit.

At the project's outset, students draw on lived experiences rooted in their local social, cultural, political, emotional, and material contexts. As these experiences evolve into tangible artefacts they reveal the entanglement between inner worlds and external environmentswhere no element can be understood in isolation and each shapes the others within a larger whole. Re-engaging the body makes these interactions central to understanding, fostering attentive listening and empathy toward surrounding contexts. This approach encourages architectural expressions that are finely tuned to the specificity of place, allowing knowledge to emerge organically from dynamic human–environment interactions. Rather than prescribing fixed ideologies or values, it supports a continually renewed understanding of the interconnectedness of materials, people, and the worlds they inhabit.

In conclusion, this elective demonstrates how embedding embodied methodologies in architectural education cultivates an awareness and empathy for the interconnectedness of human and more-than-human worlds. Through direct engagement with materials and experience-led processes, students uncover the agency of matter and their own situatedness within complex, networks, challenging anthropocentric biases and extractive regimes. This fosters an ontology of interconnectedness and mutual respect, enriching architectural expression and supporting an ethics of care within a situated context. Crucially, these outcomes are rooted in the development of tacit knowledge, an embodied understanding that enables designers to navigate complexity with sensitivity. In doing so, the course seeks a model of practice-readiness that moves beyond technical competence, preparing graduates to engage with professional contexts in ways that are situated, adaptive, relational, and attuned.

Fig. 4. Sequential documentation of a single student’s staged installation illustrating the unfolding of an atmosphere. Materialised in Plaster of Paris and shaped through responsive lighting, the images document tuned spatio-affective moments designed to evoke the qualities of a particular atmospheric memory. 2024.

Care for self, care for others, care for the world.

In the third year Architectural Theory and Design studio course students counter the lingering colonialist canon by making Indigenous forms of knowledge visible through an "embodied re-membering of the past … against the colonialist practices of erasure and avoidance"(Barad 2017, 56). Through personal spatial narratives in the first project of the year entitled Manifesto, students develop conscious and critical self-awareness of their own design practice methods, processes and fascinations. Through unearthing tacit design knowledge, students and educators demonstrate care, care for their own and each other’s spatial histories, care for expanding an architectural canon to include local ways of knowing, and, by extension, care for diverse worldviews.

The personal spatial narrative is a memory drawing fleshed out into a narrative, akin to Bachelard's primal images where, "each one of us, then, should speak of his roads, his crossroads, his roadside benches; each one should make a surveyors' map of his lost fields and meadows…Thus we cover the universe with drawings we have lived. These drawings need not be exact. They need only to be tonalized on the mode of our inner space" (Bachelard 1994, 11–12) Each of us is an accumulation of spatial memories. Our perception of space accumulates layer upon layer from spaces we have lived in, experienced, studied, analysed or designed. Our development as designers is punctuated by meaningful connections to several significant physical environments beginning in childhood (Marcus 1995). Personal spatial narratives unearth that place attachment, the bonding to a particular place in our past. Merging multi-dimensional models from Scannell and Gifford (2010) and Raymond, Brown, and Weber (2010), place attachment is theorised as being made up of three overlapping dimensions. Place identity reflects the physical, built, or natural, character of a place. Social bonding reveals the personal or communal bonding to a place through affective behaviour, cognition or social and cultural identity. Nature-bonding reflects the affinity or connectedness to nature.

How does one unearth this personal, spatial, lived experience, separate from the ways in which students are enculturated to think about architecture through their formal architectural education? The act of hand-drawing offers a means to tap into memories of lived spatial experiences outside of language. Drawing transcends the limitations of institutional languages, such as English, which often lack the nuance required to describe spaces tied to African cultural memory and identity (Elleh 2022). In this way, drawing is used as a tool to think about things unknown; "it offers ways of knowing, thinking and doing that link cognitive, affective and practical modes of study”(Adams 2017, 248). Drawing is used, as a trowel to open up, feel one's way forward (Ingold 2013) and explore the archaeological sites of the students' past lived spatial experiences. Drawing is an embodied and phenomenological exercise which "echoes in the measurements of our body and in the memories of our minds…, expresses our relationship with the world but at the same time reinforces our self-identity" (Pallasmaa 2013, 76). The personal spatial memory drawing can thus be seen as an act of self-care, connecting the self’s past with the present.

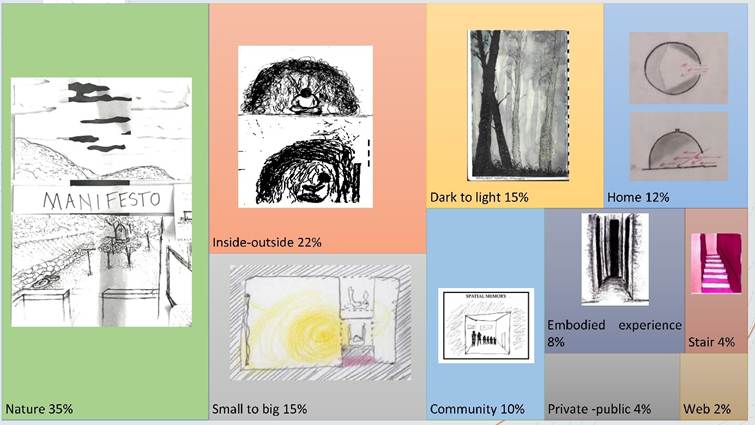

The personal spatial narrative method unearths these dimensions of the designer's place attachment and asks how these are reflective of a particular design voice or way of seeing and being. Students’ personal spatial narrative drawings reflect these places attachment dimensions with 35% of students’ memories reflecting nature bonding, whilst 22% deal with the threshold between the internal, world and the outside natural world. Interestingly 12% reflected home, and 10% were memories involving community and family (refer Figure 5).

Fig. 5. Personal Spatial Memory drawings breakdown of categories showing that 35% of student personal spatial memories display natural bonding

These personal spatial memory drawings echo Cooper Marcus' “environmental autobiographies” (2014, 32) and Aldrich's "repertory grids"(2005) in uncovering place attachment, providing continuity with the students' past, a sense of control, self-determination and a sense of identity of who they are and where they came from.

The archetypal spatial fascination unveiled in the students' personal spatial memory is compared to a deconstructed archive[1] of their past practice to see if it re-occurs and how it has been explored. These two methods are self-reflective; the students look within themselves, into their past practice, and to dominant spatial memories within their childhood, to unearth tacit knowledge about their design practice and who they are as designers. Following this inward-looking process, students then look outward to the institution, to architectural discourse and practice, asking themselves where, or even if, they fit in. In the context of a decolonial university, many students struggle to find their place.

The roots of an architect's spatial intelligence lie within their personal lived spatial experience and in the studios of architectural education. Students whose personal habitus (Bourdieu 1977) mirrors that of the architectural institution are seen to be higher-functioning by their teachers and thus the institution replicates and reinforces its own established habitus (Payne 2015; Stevens 2002). Historically, in South African architectural institutions, those students whose habitus differed from that of the institutions have been othered and expected to conform. Validating their lived spatial experience in the South African context validates a way of being and knowing about space and architecture that is very different from the colonial hegemony that still lingers in these institutions. These ways of being and knowing originating from the student's lived spatial experience before they enter formal architectural education, are key for students' ability to acknowledge and even challenge institutional influence.

Personal spatial narratives reveal the student’s affective place attachment through a memory and meaning-making process, prompting them to understand where their design fascinations originate. Revealing this tacit knowledge(Polanyi 1966; 1958) about their own design fascinations makes students more conscious of their design predispositions in their design projects during the rest of the year. These design predispositions and fascinations reveal that design practice is “informed by personal preferences (and) cultural context…(bringing) insight into various dimensions of the tacit” (Schrijver 2021, 8). Students first unearth tacit design fascinations from their lived past experiences, then they explore these in the design studio, and lastly they reflect on the process, through “reflective practitioner”(Schon 1984) essays showing that they knew more than they could tell, borrowing from Polanyi (1966, 11). This tacit knowledge assists undergraduate students to begin to define their own design practices ahead of a compulsory year out[2] before returning for postgraduate study, “it just helps you steer your career a bit more… it gives you a starting point of where you think that you want to be or would like to head in the direction of.” (Student Focus Group 2, 2024). The impact of unearthing this tacit design practice knowledge was clear: “I was able to discern exactly where that gut feeling came from, what I was trying to accomplish and how I could do it better, or even how I could do something completely different.” (Student4782-2022, Final Reflective Essay)

This inward-reflective and outward-diffractive process validates diverse worldviews, ways of being, and knowing that were actively denied and delegitimised. This "embodied re-membering of the past" (Barad 2017, 56) or reconstituting of alternative histories validates the "alternative ways of doing things", practices which are embedded in alternative knowledges (Smith 2012, 52). Therefore, care is nurtured, not only in the care of the self but also in the care of others, for many ways of knowing, for extending the canon with diverse worldviews. Students situate themselves within these diverse ways of being, knowing and designing, and thus develop practice-readiness by knowing where their strengths lie, developing conscious awareness and confidence in their ability to deal with the uncertainty and multiple crises that practice might bring, but also agency in being able to contest the lingering colonial and capitalistic norms of practice.

Conclusions-Strategies of micro-resistances

The above case studies of architectural pedagogy demonstrate practice-readiness strategies of care that include micro-resistances against extractivist tendencies in architectural education. The case studies explore the co-existence and validation of alternative paradigms and worldviews through cultivating social, material or mnemonic tacit knowledge.

The empathic social-relational intuition cultivated in first year is extended to material engagement in the second-year elective, and further to surfacing design instincts rooted in cultural lived spatial experiences in third year. Together these pedagogical strategies develop care for each other, for the material world, and for themselves and their particular cultural worldviews.

In the first year, students explore alternative worldviews inherent in indigenous knowledge through social, collaborative and communal engagement, thereby broadening their views of themselves and the world around them. Coming into University from diverse socio-economic and cultural backgrounds, Character-Led Design is used as a basis for beginning to understand the students' position and situatedness in relation to alternative worldviews, validating these alternative forms of knowledge and building the “pluriversity” (Reiter 2018, x)(Reiter 2018, x). The first-year plants the seed for inclusive practice by encouraging the sharing and understanding of each other’s perspectives, thus cultivating empathy and social consciousness. This student-led approach teaches educators to listen and take on the role of facilitators in the design studio. Additionally, it introduces students to collaborative design practices early in their architectural education, with the hope that they will challenge and transform traditional top-down practices in the future. In Focus Group Discussions, postgraduate students noted that the Character-Led Design technique resurfaced from their subconscious during their thesis work.

“It's interesting how something that we learnt about in first year, which I didn't appreciate as much back then, helps inform my projects now. It stayed in my subconscious, and it manifested in me as a more experienced designer, which I thought was quite interesting.” (Student’s Focus Group Discussion on Narrative in the Design Process, September 2024)

This social-relational empathy, and the acknowledgement of diverse worldviews in first year is broadened to include non-human matter and material agency in the second-year elective. Embodied understandings of material agency are cultivated through exploring embodied material and sculptural entanglements with their own lived experiences.

In the third year, personal spatial narratives connect students with their local ways of seeing, knowing, and being. Through reflecting on memories, spatial archetypes are unearthed, which are then explored generatively in design projects during the rest of the year. The personal spatial memories and their resultant spatial archetypes reveal the roots of the students' worldviews, thus developing their own particular design voices.

These spatial archetypes, that first emerged through inhabiting perspectives different from their own in first year, are further explored through material engagements in the second year and then further unpacked in the third year (Figure 6). Students see these processes as meaningful beyond the scope of the courses: "Pay dividends in self-awareness and design response…, seeing patterns re-emerging in Honours (Student 6755, 2022, Focus Group)”.

These design voices/worldviews are then situated within the institutional worldview, with students gaining critical agency to accept, reject, or transform their institutions' habitus.

Fig. 6. Images evidencing personal spatial archetypes explored through a first, second and third year in one student's body of work.

Thus, in building a student's own design voice and exposing them to multiple and diverse worldviews through social and material interactions, students' conscious self-awareness, critical positionality, and care are cultivated.

By the third year, care for the environment becomes intertwined with care for the self. Through this process, students develop a conscious awareness of self within the institutional worldview. These strategies counter extractive attitudes by positioning the student as a thinking, feeling, and encountering body within the design process, deeply embedded in local contexts. This experience provides a valuable counter to extractive industry practices. It re-envisions the role of the architect not as a solitary visionary hero, a trope typical of Western architectural practice, but as a living being entangled and part of a myriad complex web of living worlds.

Care in architectural pedagogy can also be seen as a radical decolonial practice, especially in the context of a post-colonial university. Students' responses to care in the pedagogy varied. Nonetheless, it was clear from focus groups that black women students in particular, attributed improved confidence in their own practices to the care, consideration, and nurturing they felt (Student Focus group 1, 2024). This confirms research findings that care needs to be foregrounded to support black women in higher education[1].

This validation is an act of decoloniality, resisting the erasure and invisibility of local forms of knowledge. It unearths and validates diversity and works to create social justice and inclusivity in institutions where students are taught "excellent skills that would prepare them to practice architecture globally, while at the same time… displacing their individual, group and post-colonial national memories and identity” (Elleh 2022, 719).

These strategies are, however, also relevant to sites of architectural education in the global north. The dichotomy of seeing the world as the colonising north versus the colonised south belies migratory patterns of students. Institutions of architecture have an increasingly diverse cohort of students, linguistically, culturally, and racially. Therefore, the validation and co-existence of diverse worldviews and alternative paradigms is potentially generative and an act of freedom for students in all institutions.

In conclusion, the pedagogical strategies of care explored in this paper seek to cultivate socially conscious, critically engaged, and practice-ready graduates. Architectural education can move beyond extractive and colonial legacies by foregrounding tacit and embodied knowledge, validating diverse worldviews, and centring care. These practices operate as micro-resistances within entrenched systems, creating spaces where alternative ways of knowing and being can emerge.

Care reframes practice-readiness as more than technical proficiency, emphasising empathy, responsiveness to tacit cues, and attentiveness to human, non-human, and more-than-human entanglements. In doing so, it equips graduates to contribute to a more just, inclusive, and sustainable profession while also transforming students’ own experience of education into one that is affirming and inclusive. Ultimately, this approach offers a generative model of architectural pedagogy for navigating the complexities of a shared and fragile world.

References

Abdi, Ali A. 2003. ‘Apartheid and Education in South Africa: Select Historical Analyses: Western Journal of Black Studies’. Western Journal of Black Studies 27 (2): 89–97.

Adams, Eileen. 2017. ‘Thinking Drawing’. International Journal of Art & Design Education 36 (3): 244–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12153.

Alaimo, Stacy. 2018. ‘Trans-Corporeality’. In Posthuman Glossary, edited by Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova. Bloomsbury Academic.

Aldrich, Tony. 2005. ‘Self Awareness and Empowerment in Architectural Education’. In New Practices - New Pedagogies: A Reader. Routledge. https://go.exlibris.link/7MJ2LcfQ.

Bachelard, Gaston. 1994. The Poetics of Space. Beacon Press.

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press. https://go.exlibris.link/PTR7DH76.

Barad, Karen. 2017. ‘Troubling Time/s and Ecologies of Nothingness: Re-Turning, Re-Membering, and Facing the Incalculable’. New Formations 92 (92): 56–86. https://doi.org/10.3898/NEWF:92.05.2017.

Bazana, Sandiso, and Opelo P. Mogotsi. 2017. ‘Social Identities and Racial Integration in Historically White Universities: A Literature Review of the Experiences of Black Students’. Transformation in Higher Education 2 (November). https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v2i0.25.

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. ‘Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction’. In Power and Ideology in Education, edited by J Karabel and AH Halsey. Oxford University Press.

Braidotti, Rosi. 2013. The Posthuman. Polity.

Brookfield, Stephen D. 2017. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass, Wiley.

Elleh, Nnamdi. 2022. ‘African Studies Keyword: Okà’. African Studies Review 65 (3): 717–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2022.87.

Field, Syd. 2005. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Rev. ed. Delta Trade Paperbacks.

Griffero, Tonino. 2016. ‘Atmospheres and Felt-Bodily Resonances’. Studi Di Estetica, no. 5 (June): 5. https://journals.mimesisedizioni.it/index.php/studi-di-estetica/article/view/457.

Grimaldi, Silvia, Steven Fokkinga, and Ioana Ocnarescu. 2013. ‘Narratives in Design: A Study of the Types, Applications and Functions of Narratives in Design Practice’. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces, September 3, 201–10. https://doi.org/10.1145/2513506.2513528.

Gromark, Sten, Jennifer Mack, Roemer van Toorn, Hélène Frichot, Gunnar Sandin, and Bettina Schwalm, eds. 2018. Architecture in Effect. Actar Publishers.

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press Books.

Hein, Carola, ed. 2017. The Routledge Handbook of Planning History. 1 Edition. Routledge.

Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge.

Jansen, Jonathan D., ed. 2019. Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge. Wits University Press. https://doi.org/10.18772/22019083351.

Kahn, Louis I., and John Lobell. 2008. Between Silence and Light: Spirit in the Architecture of Louis I. Kahn. Boston: Shambhala.

Krasny, Elke, and Fitz, eds. 2019. Critical Care: Architecture and Urbanism for a Broken Planet. Architekturzentrum Wien. https://go.exlibris.link/h8rxdKgX.

Le Roux, Hannah. 2022. ‘The Department of Invention’. In Redical Pedagogies. MIT Press.

Marcus, Clare Cooper. 1995. House as a Mirror of Self: Exploring the Deeper Meaning of Home. Conari Press. https://go.exlibris.link/cd5lXbTg.

Marcus, Clare Cooper. 2014. ‘Environmental Autobiography’. Room One Thousand, 2, no. 2: 12. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1rr6730h.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2009. The Thinking Hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture. 1st edition. Wiley.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2013. Encounters 1 Architectural Essays. 2nd edition. Rakennustieto Publishing.

Payne, Jennifer Chamberlin. 2015. ‘Investigating the Role of Cultural Capital and Organisational Habitus in Architectural Education: A Case Study Approach’. International Journal of Art & Design Education 34 (1): 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12018.

Polanyi, Michael. 1958. Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/P/bo19722848.html.

Polanyi, Michael. 1966. The Tacit Dimension. Doubleday & Company INC.

Polanyi, Michael, and Amartya Sen. 2009. The Tacit Dimension. University of Chicago Press.

Raymond, Christopher M., Gregory Brown, and Delene Weber. 2010. ‘The Measurement of Place Attachment: Personal, Community, and Environmental Connections’. Journal of Environmental Psychology (Netherlands) 30 (4): 422–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.08.002.

Reiter, Bernd, ed. 2018. Constructing the Pluriverse: The Geopolitics of Knowledge. Duke University Press.

Scannell, Leila, and Robert Gifford. 2010. ‘Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework’. Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.006.

Schon, Donald A. 1984. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think In Action. Basic Books.

Schrijver, Lara. 2021. ‘Introduction: Tacit Knowledge, Architecture and Its Underpinnings’. In The Tacit Dimension, edited by Lara Schrijver. Leuven University Press. https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461663801.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Third edition. Bloomsbury Academic.

Stevens, Garry. 2002. The Favored Circle: The Social Foundations of Architectural Distinction. New Ed edition. The MIT Press.

Tronto, Joan C. 1998. ‘An Ethic of Care’. Generations 22 (3): 15.

Tronto, Joan C., and Berenice Fisher. 1990. ‘Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring’. In Circles of Care, edited by E. Abel and M. Nelson. SUNY Press.

Short CV

Sandra Felix is an architect-educator-researcher with more than 25 years of practice experience in South Africa. She co-founded Greenbrick Design an interdisciplinary architecture and landscape design practice. She teaches at the School of Architecture and Planning of Wits University, and is completing her PhD at the intersection of self-ethnographic practice-based design research and architectural pedagogy.

Dr. Brigitta Stone-Johnson - is an Architect, Fine artist, and creative researcher who lives in Johannesburg, South Africa. She has been a lecturer and creative practice researcher at the Wits School of Architecture since 2016. Her research situated in the Environmental Humanities field, Her research and creative practice consider vital materiality and the Anthropocene through collaborations with more than human oddkin, such as local stone, tar, rubble and plastic, in post-extractive urban terrains. Her PhD entitled' wayfaring stone' (2023), focuses on stone as a vibrant social matter in the post-extractive urban terrains of Johannesburg.

Anita Szentesi is an architect, filmmaker, lecturer, and researcher, currently situated at the University of the Witwatersrand School of Architecture and Planning in Johannesburg, South Africa. In her research she identifies that diverse and complex relationships exist between people, culture, identity, history and buildings and places. She proposes a design methodology called character-led design, which combines architecture and film, to explore possibilities to engage new ways of designing to achieve socially conscious place-making, and new ways of communicating the complexities of life in design representations.

Dirk Bahmann is an architect, fine artist and researcher practising in Johannesburg, South Africa. He lectures at the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand, oversees the s'Fanakalo makerspace and is pursuing a creative practice doctoral research jointly at the Wits School of Arts and the School of Architecture and Planning. Central to his research is to understand the ineffable affective qualities that spatial and architectural atmospheres have on its audiences.