The Hybrid Network Model calls for a Water Ecosystems

Paradigm Shift in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta / El modelo de red híbrida exige

un cambio de paradigma de los ecosistemas acuáticos en el delta vietnamita del

Mekong / Modelos de redes territoriais e transformações socioecológicas no

delta do Mekong, no Vietnã

Nguyen, Sylvie Tram1

1.

Wageningen University Research, Soil Geography and Landscape Group, The Netherlands,

sylvie.nguyen@wur.nl, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6619-5555

Received:

07/03/2025

Accepted:

28/08/2025

DOI:

https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/astragalo.2025.i40.09

Abstract

As one of the

world's largest rice exporters and most vulnerable low-lying deltas, the

Vietnamese Mekong Delta (VMD) has undergone radical territorial transformations

primarily for agricultural purposes. However, human-induced water

techno-managerial changes, coupled with climate change and sea level

rise—causing flooding, drought, salination, subsidence, and biodiversity

loss—have disrupted the Delta’s natural processes. This research investigates

how these alterations exacerbate climate change impacts by analyzing

human-induced fabric patterns. Employing Corboz’s Palimpsest method, a

mapping analysis identified three dominant territorial configurations: 1) Star

Node Connectivity, 2) Agrarian Grid Compartmentalization, and 3) Hybrid

Diffusion. The Star Network Model aligns with Desakota rururban patterns

observed along water infrastructure. The Gridded Network Model emerges from

large-scale hydraulic projects that fragment water ecosystems. The Hybrid

Network Model integrates built and natural landscapes, revealing adaptation

potential. While the other two models inadvertently disrupt natural systems,

the Hybrid model inclines to prioritize water and infrastructure in

constructing diversified ecosystems, thereby providing insights into future

resilience strategies. The study proposes reframing these models as Social

Ecologies to foster resilience through a paradigm shift wherein the Mekong

Delta is regarded as a subject and agency within the Ecological Transition.

Thereby integrating livelihoods, and infrastructure in harmony with the Delta’s

natural ecosystems. The findings regarding the Network Models facilitates an

understanding of anthropogenic impacts across the territory and approaches to a

more resilient Mekong Delta.

Keywords: territorial

alterations, climate change resilience, social-ecologicies, network models,

Mekong Delta adaptation

Resumen

El delta

vietnamita del Mekong (DMV), uno de los mayores exportadores de arroz del mundo

y uno de los deltas más vulnerables, ha sufrido alteraciones territoriales

radicales para la agricultura. Sin embargo, los cambios inducidos por el

hombre, junto con el cambio climático y la subida del nivel del mar —que

provocan inundaciones, sequías, salinización, hundimiento y pérdida de

biodiversidad—, han alterado los procesos naturales del delta. Esta

investigación examina cómo estas alteraciones agravan los efectos del cambio

climático mediante el análisis de los patrones del suelo inducidos por el

hombre. Utilizando el método del Palimpsesto de Corboz, un análisis

cartográfico identificó tres configuraciones territoriales dominantes: 1)

Conectividad del Nodo Estrella, 2) Compartimentación de la Red Agraria, y 3)

Difusión Híbrida. El Modelo de Red en Estrella se alinea con la urbanización al

estilo Desakota a lo largo de la infraestructura hídrica. El Modelo de

Red Compartimentada es el resultado de proyectos hidráulicos a gran escala que

fragmentan los ecosistemas acuáticos. El Modelo de Red Híbrida integra paisajes

construidos y naturales, revelando el potencial de adaptación. Aunque todos los

modelos han perturbado involuntariamente los sistemas naturales, proporcionan

información sobre futuras estrategias de resiliencia. El estudio sugiere

replantear estos modelos dentro de los marcos de los sistemas

socioecológicos para fomentar la resiliencia mediante la integración de los

medios de subsistencia, las infraestructuras y los ecosistemas naturales. Las

conclusiones pretenden mitigar los impactos antropogénicos y apoyar un Delta

del Mekong más adaptable.

Palabras clave: alteraciones territoriales, resiliencia al cambio climático, sistemas

socioecológicos, modelos de red, adaptación del delta del Mekong

Resumo

O Delta do Mekong

vietnamita (VMD), um dos maiores exportadores de arroz do mundo e um dos deltas

mais vulneráveis, passou por alterações territoriais radicais para a

agricultura. No entanto, as mudanças induzidas pelo homem, juntamente com as

mudanças climáticas e o aumento do nível do mar — causando inundações, secas,

salinização, subsidência e perda de biodiversidade — interromperam os processos

naturais do Delta. Esta pesquisa examina como essas alterações exacerbam os

impactos da mudança climática por meio da análise dos padrões de terra

induzidos pelo homem. Usando o método Palimpsesto de Corboz, uma análise

de mapeamento identificou três configurações territoriais dominantes: 1)

Conectividade de Nó Estrela, 2) Compartimentação de Grade Agrária e 3) Difusão

Híbrida. O modelo de rede em estrela se alinha à urbanização no estilo Desakota

ao longo da infraestrutura hídrica. O modelo de rede em grade resulta de

projetos hidráulicos de grande escala que fragmentam os ecossistemas aquáticos.

O modelo de rede híbrida integra paisagens construídas e naturais, revelando o

potencial de adaptação. Embora todos os modelos tenham interrompido

involuntariamente os sistemas naturais, eles fornecem informações sobre

estratégias de resiliência futuras. O estudo sugere a reformulação desses

modelos dentro das estruturas do Sistema Social-Ecológico para promover

a resiliência por meio da integração de meios de subsistência, infraestrutura e

ecossistemas naturais. As descobertas visam mitigar os impactos antropogênicos

e apoiar um Delta do Mekong mais adaptável.

Palavras-chave: alterações territoriais,

resiliência às mudanças climáticas, sistemas socioecológicos, modelos de rede,

adaptação ao Delta do Mekong

1.

Introduction: The Mekong Delta and Anthropogenic Transformations

As a low-lying Delta, the Vietnamese

Mekong Delta (VMD) is one of the third-largest Deltas on Earth. Due to its high

agricultural production, the Mekong Delta is a densely populated region of over

17 million and a significant global and regional food security hub (Schmitt and

Minderhoud 2023). Known as the ‘Ricebowl’ of Vietnam, the VMD has undergone

radical territorial alterations to convert its Deltaic landscapes into

agriculture. Since the 1990s, it has become one of the world's largest rice

exporters, with a 50% National yield and 80% total exports. Despite this

success, it has come at the cost of systemic ecosystem loss resulting from

imposed engineering structures, which have obliterated the Delta’s natural

regenerative ecosystem processes (Scown et al., 2023), exacerbating the impact

of climate change and sea level rise, with vulnerable areas in Deltas

experiencing heightened levels of flooding, drought, salination, subsidence,

loss of sedimentation, and biodiversity loss (Scown et al. 2023, Syvitski et

al. 2022, Syvitski 2008, Edmonds et al. 2020).

The Mekong

Delta’s former regenerative processes, once aligned with ecological values

based on deltaic ecosystems, have almost been completely obliterated in favor

of models in water technological and managerial processes in hydraulic

engineering. Investments in optimized ecosystem services in favor of

agricultural production have propelled agrarian progress and transformed the

Mekong Delta into an efficient food production region, at the expense of the

Delta’s water ecosystems. And the Delta’s natural ecosystem processes have consequently

become compounded by the combined impact of these human-induced alterations and

adverse climate change trends, including flooding, drought, salinization (Eslami et al. 2021), sea level rise, and other anthropogenic processes

like reservoir dams, sand and groundwater extraction, and pesticide use,

causing decreased sedimentation (Kondolf et al. 2018),

increased tidal flooding (Eslami et al. 2019),

and accelerated land subsidence (Minderhoud et al. 2017; 2020). The combined pressures threaten the future of the Mekong

with drowning and call for decisive actions (Eslami et al. 2019).

Consequently, the research seeks

to elucidate the types of territorial configurations or fabric patterns that

have been shaped by human-induced processes across the Mekong Delta.

Furthermore, it investigates the underlying agencies responsible for these processes

and their transformative impact on the delta’s natural ecosystems.

2. Brief historical overview of

the Mekong Delta’s transformation

Centralized and decentralized

mechanisms driven by investment in hydraulic technology and managerial water

policy (Evers et al. 2009) have radically altered the delta, consequently

transforming its territory against the laws of nature. My research findings

reveal different resulting territorial configurations—defined here as Network

Models—which have emerged due to key historical events. From the dredging of

the first navigational canals during the early French Colonial period in the

1880s, to the artificially devised watershed management zones by 1975, new

water lines have been incrementally added. Which followed by the expansion of

these irrigation systems with added hydraulic projects composed of dikes,

sluice gates, and pumping systems, during the Green Revolution in the '90s, and

larger-scale hydraulic projects to mitigate adverse environmental impacts by

the early 2000s.

Key historical events have

incrementally driven the delta’s water territorial transformation. The first

traces of canals were set in place during the Nguyen Dynasty (Le Coq, Trébuil

and Dufumier 2004) and the first navigational canals were dredged during the

French Cochinchina period as primary canal systems planned for easy water

traffic navigation between urban centers (Brocheux 1995; Biggs et al. 2009; Biggs 2010).

However, the most rapid progress in canalization occurred after the Vietnam War

in 1975, due to political shifts that advanced water technological and

managerial ingenuity. Nevertheless, since water engineering knowledge was

transferred from the new Central Government located in the North (Arwin van

Buuren 2019; Minkman Buuren, and Bekkers, 2021), it was far removed from the

local ecological wisdom shared by the locals living in the Delta over the last

century (Ehlert 2012; Liao et al. 2016). Moreover, new agrarian production

incentives promoted the postwar movement to the Southern Frontier, whereby

farmers returned to the countryside (Le Coq, Trébuil and Dufumier 2004).

New knowledge of water management was

promoted by the Dutch Water Sector through high-level bureaucrats and

implemented by embassies and engineering consultants to translate the Dutch

Delta Approach (DDA) (van Buuren 2019). Thus, Newfound

DDA in the Netherlands was transferred to the Mekong Delta as one of the first

Southeast Asian countries to successfully adopt the Dutch water management

plans, first during the establishment of the Mekong Delta Management Plan (MDP)

in the 1970s and further after the renewal of the bilateral collaboration

between the Dutch and Vietnamese in 2008.

In these ways, the 1975 reunification

and subsequent 1986 Doi Moi reform period led to land management changes in

support of a Green Revolution. From the campaign for National food security to

the episodes of devastating flood events, the emergent state of fear raised

after the war had driven investment in water infrastructure advancement. The

subsequent campaign to dredge canals and reform water policy changed the

positions of power, by promoting the Green Revolution in the 90s, becoming a

major political shift thereafter (Brocheux 1995; Biggs et al. 2009).

Although these new reforms profoundly

improved the Delta’s water ecosystem through productive processes, they

unintentionally turned ecosystem processes away from the Delta estuary’s

natural cycles. In response to increased flooding and demand for rice production,

canals were extended and mechanized by the late 1990s. Access to new

infrastructure consequently attracted unplanned waterfronting linear urban

settlements, which exerted pressure on them. Hence, processes once in tune with

the cyclic cycles of the monsoon in wet and dry seasonal patterns had been

superseded by more predictable unnatural processes, in favor of flood

protection for safe habitation and revenue in mass rice production. New

progress in technical mechanisms included the coordination of irrigation

channels incorporated with sluice gates, pumping stations, weirs and dikes (Le

Coq, Trébuil and Dufumier 2004).

Furthermore, States of the

Anthropocene, encompassing subsidence, salination, water pollution, groundwater

depletion, and sedimentation loss, were increasingly felt by the late 1990s and

early 2000s. All of which were anticipated in subsequent Mekong Delta

Management reports: NEDECO, Mekong Delta Plan and Mekong Delta Integrated

Regional Plan (NEDECO 1993; The Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the Kingdom

of the Netherlands 2013, 2020; Toan 2014). Despite these warnings, the

agricultural sector continued to suffer the consequences of environmental

degradation well into the 2010s, from water pollution to soil contamination,

questioning the Mekong Delta’s complete devotion to intensified rice

production.

3. Hypothesis and Perspective

Following Vietnam’s Green Revolution,

the process of water resource extraction and land appropriation completely

altered the state of the Delta's water ecosystem. Moreover, the appropriation

of territory as spaces for production and habitation created different deltaic

formations. Different configurations are identified as our ‘Network Models’ and

characterized as overlapping and competing spatial formations composed of fabric

patterns. These research findings shall be further elaborated on from our mapping

analysis in subsequent sections.

It is hypothesized that the gradual formation

of these Network Models has increasingly ignored the Mekong Delta’s natural

water ecosystem, in favor of systematic progress. This points towards a need for

a paradigm shift to address the Mekong Delta’s heavily altered water management

system. To reverse this trend, the Mekong Delta must be recognized as a subject

of Ecological values, rather than the object of ecosystem services. In

the effort to prevent the further state of Anthropocene, the Delta must act as

an active agent in its land and waterscapes. Only by reversing the gaze could

the Delta reclaim its role in sustaining resilient Social Ecologies.

To foster an Ecological Transition

between human and natural processes, leading to their integration into a second

nature, strategic novel approaches must be devised. By reframing the Delta as

an agency for the Ecological Transition, the research focuses on building an

understanding of the spatial anthropogenic changes made across the region and

the different agencies behind them, as a catalyst for strategic Deltaic

adaptation. Therefore, identified Network Models shall be extracted to be

further investigated and characterized through the palimpsest analyses.

Emergent patterns found in the Mekong Delta’s fabric shall present the

construction of layers over time, to build narratives of how the Mekong Delta

has arrived at such an Anthropogenic structure.

Figure 1 shows the location of the

detailed study area, located in the upper alluvial region of the Mekong Delta,

directly south of the Bassac River and the Long Xuyen Quadrangle[1] and Can Tho. The

middle image in Figure 1 shows the zoomed-in case study area. And to the

right, the detailed study area is shown; for clarity, the frame has been

rotated north-west, and covers part of the Long Xuyen Quadrangle and Can Tho

region. Therefore, all the mapping studies in this section shall be based on this

frame.

Figure 1.

Study area location map, set in Long Xuyen Quadrangle and the western portion

of Can Tho province. Source: Author 2022. Datasource:

Google Earth accessed 2019, OpenStreet-Map, accessed 2019.

When

the first traces of canals were dredged before the 1800s, sparse linear

settlements colonized the edges of the canals as natural sedimentation built up

on both sides, creating a natural protection area from the rising waters. The

diagrammatic section in Figure 2, shows the hypothetical relationship of the

first stilt houses along the canal embankments, surrounded by forested areas. Ricefields,

most likely cultivated as floating rice paddies, were likely cultivated in the

swampy land beyond.

Figure 2.

Diagrammatic canal section in the 1800s, with levees colonized by stilt houses

and forest.

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of

water networks and urban growth over the decades. The map in the 1930s depicts how

the first traces of canals were dredged over the swampy landscape, original

alignments which has remained largely unchanged. By 1988, secondary and

tertiary canals were constructed, and sparse linear settlement development emerged

along the main canal corridors, and primary roads were planned alongside

canals. In 2003, the nodal town expanded along with the principal city of Can

Tho, and linear settlements further developed along primary canals. By 2016, rapid

urban development and increased linear intensification along most canals exerted

more pressure on existing conditions.

a.

1930

b.

1988

c.

2003

4. Research Methodology

Please be advised that the subsequent

mapping analysis in the following section shall not be based on a chronological

sequencing of the territory. Instead, Network Models shall be identified and

extracted from the fabric based on the hypothetical relationships established

by different agencies. As such, the justification of transformations shaping

the new Delta shall be made through identified actors found therein. This

approach of defining Network Models between configurations of urban spaces,

elements, and layers of pattern formations ultimately identifies newfound

heterotopic relationships, drawing inspiration from David Grahame Shane's urban

design methods in conceptual modeling (Shane 2005, 2021).

The research method is based on a

layered mapping approach, adopted from Corboz’s land in Palimpsest

methodology (Corboz 1983), which is built upon the superposition of layers of

historical constructs, and the use of figure-ground concepts based on Colin

Rowe’s Collage City (Rowe and Koetter 1978). For instance, novel forms

of boundaries, spaces, or limits were identified to have taken shape due to

different water controls across the territory, pushed by various centralized

and decentralized mechanisms. Driven by various geopolitical agencies, these processes

have transformed the Mekong Delta's once deltaic ecosystem, resulting in different

fabric patterns.

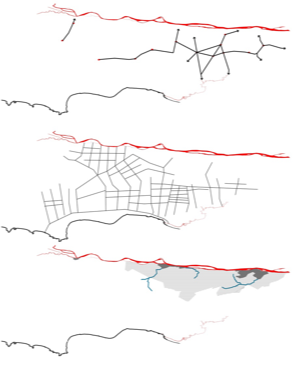

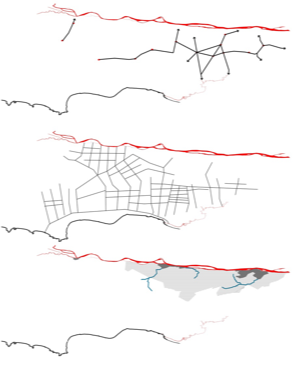

The anthropogenic relationships

created distinct forms of rationalities whereby various boundaries were set

apart, as illustrated in Figure 4. They have emerged from intricate Social

Ecological interactions between the Delta's ecosystem and various processes,

including urbanization or industrialization progress, technological

advancement, and social or societal interactions. Through a layered mapping

analysis of the territory, three distinct figures of territorial development

were identified. Each of these models exhibits unique configurations, albeit with

overlapping elements. As mapped in Figure 4, each network model was extracted

as a diagram, which serves as a conceptual abstraction of the traces that have

ultimately shaped the Delta’s development pattern.

Consequently, the research has identified

three distinct territorial configurations prevalent across the Delta region,

collectively referred to as Network Models, as illustrated in Figure 4.

These resulting models were shaped by diverse actors and agencies and have been

categorized into three distinct types: Network Models of Stars, Grids, and

Hybrids. A description of each Network Model is provided below:

1) Stars, Nodal Connectivity

The activities linkages, attracting urban growth between

the urban-rural territories, specifically along key water and road corridors.

2) Grids, Agrarian Compartmentalization

Irrigated fields, resulting from centralized and

decentralized water management for rice production, led by hydraulic societies.

3) Hybrids, Urban-rural Diffusion

The diversified landscapes, comprised of farming units

inhabited by riverine-based locals, combining elements from Stars and Grids.

Figure 4. Conceptual

diagrams of network models: Stars, Grids and Hybrids (top to bottom). Source: Author, 2022. Datasource: Google Earth accessed 2019,

OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

5. Results of the Palimpsest Atlas

Analysis

5.1 Network Model 1: Star Node

Connectivity

In the context of navigation and

trade, the first canals were dredged by the French Colonies for strategic water

navigation purposes, they were planned to link trade centers and urban towns.

These canals were designed as radiating networks that intersected urban centers

and linked across the Bassac River and seaports. The canals were designed based

on traffic flow capacity, informed by road transportation planning principles.

The linkage between nodal towns established at joint water and land intersections

was therefore planned similarly to roads. Whereby, the water channels

facilitated transportation by directly linking towns to industrial, market, and

trade zones. Which resulted in the formation of many radial stars and axial

corridors between destination nodes, liken to the boulevards found in Paris

(Brocheux 1995; Biggs 2010). Therefore, the original rationale of canalization

during the French colonial period deviated from the natural logic of the

delta’s floodplains in favor of water navigation.

In addition, various points of

intersection have historically functioned as floating markets, serving as local

meeting points whereby merchants directly sold their goods from their boats,

mainly fruits, vegetables, and other food items. However, water commerce

activities were supplanted by 1916 due to competition with the established

Chinese communities engaged in water trade in South-East Asia. Thereafter, the

French colonies switched from water-connected commerce to road-linked,

land-based commerce activities (Brocheux 1995).

Defined as a Star Network Model,

Figure 5 illustrates the expansion of urban nodes and linear spatial

development across canals and roads as the Postcolonial fabric. This fabric is

characterized by the further growth and extension of established urban centers

and town plans at the intersection of primary canals. Nodal and linear

settlement growth at town intersections and along extended networks of roads

along the canals has further intensified. These networks have activated

linkages between places of interchange, facilitating the flow of people, trade,

commerce, industry, and floating markets. A closer look at the mapping reveals

how ad hoc linear settlements have thickened along the water canals and upon

the parallel and interconnected road networks, establishing another solid

interaction between water-driven and land-based activities.

The linear settlements along roads

and canals between nodal towns have significantly intensified over the decades,

establishing a whole new logic of urban-rural dynamics. This new dynamic has

resulted from the activation of infrastructural linkages between activities

located on and off the waterfront and on land. The formation of star and nodal

towns was planned within a walking radius of approximately 500 to 1km between

service centers. This strategic planning had attracted additional ad hoc formal

and informal linear development composed of mixed-use shophouses, accompanied

by ground-level services, including shops, markets, restaurants, and other commercial

activities.

Over time, the original nodal towns

established at the intersection of canal channels have further expanded, as

shown in Figure 6. Sprawling new linear development has emerged and is

dispersed across new secondary and tertiary water channels. The Linear settlement

originally established along the original canals has become denser with added

development, some of which is located along new internal road networks.

Activated by work-live activities, they have further grown and thickened across

the fabric, especially along the linkages near the main town centers. In this

area, the development has become thicker across multiple layers, where roads

and infrastructural networks were added. This thickening creates a palimpsest

of linear settlement patterns, which enhance the identity of the established

water channel networks while adding more pressure to land-based development,

particularly along roads.

Figure 5. Star canal

formations and expansion of urban nodes through linear development along the

colonial era canals. Source: Author, 2022. Datasource:

Google Earth accessed 2019, OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

Figure 6. Map

showing the expansion and densification of linear settlements between original

nodal towns, enhancing the radial network linkage at the intersection of canals

and towns. Source: Author, 2022. Datasource:

Google Earth accessed 2020, OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

Figure 7 shows how one of Co Do's

original nodal towns has expanded as a star formation, and linear settlements

have intensified along its canals over fewer than 20 years. Similar to the

switch from water to land-based activities identified by Phuong Nga’s mapping

of the Cai Rang waterfront community in the Mekong, the mapping shows how the

valorization of infrastructural investment in roads (doubled up from dikes) has

resulted in a turn away from waterfront activities and onto road-oriented

communications networks (Nguyen 2015).

In 1998, several remote roads were

constructed with linear settlements along the secondary canals. By 2002, the

activities had thickened in multiple layers along the north-south axis, along

the canal, and the linear settlements had expanded through the addition of road

networks that provided more access along the star webs of canals. By 2014,

large-scale developments had been planned along the web of water and road axes,

encroaching upon the agricultural fields. These new plans have provoked more

intensification not only along the axis but along the web axis, further shaping

the star pattern. By 2020, this pattern becomes filled, as the secondary canals

become more intensified with double-sided linear development and the blocks

become more fully developed.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the term

“rururbanization” was coined in France (Barcelloni and Viganò 2022), to

describe the rapid urban flight into the rural areas. This phenomenon was

further defined by Paola Viganò, as a response against the formal urban policies,

leading new villagers to construct their own homes, densifying the countryside.

Similarly, Terry McGee identified the Desakota phenomenon in South Asia

during his subsequent research (McGee 2009). Revisiting South-east Asia's Urban

Fringe, McGee reassessed the challenges of Mega urbanization, discovering a

similar dynamic, albeit within agrarian land. Known as 'city–village,' Desakota

is a phenomenon whereby the extended built area located between the agrarian

landscape is driven by the following activity flows:

"Distinctive areas of

agricultural and non-agricultural activity are emerging adjacent to and between

urban cores, which are a direct response to pre-existing conditions, time-space

collapse, economic change, technological developments, and labor force change

occurring in a different manner and mix from the operation of these factors in

the Western industrialized countries in the nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries." (Ginsburg et al. 1991)

Several authors have already

identified the Desakota Phenomenon in the Mekong Delta region, (Desakota Study

Team 2008, McGee 2009, Shannon and De Meulder 2012, De Meulder and Shannon

2018, Lawson, Guaralda and Nguyen 2022). However, this study distinguishes

Desakota activities through specific land pattern formations, defined as the

Star Network Model. This phenomenon aligned with Desakota culture, as the

linear water and parallel road network linkages attract rapidly growing ad hoc

activities, situated between urban and rural areas. This Star Network Model is

created by a hierarchy of radial linear settlement expansion patterns activated

by access to intersecting water and road infrastructure. These radial

connections provide access to economic and industrial infrastructure or

activities.

Figure 7. The expansion

of the original colonial era Star model located in Co Do town over the last 18

years. Image a. 2002; b. 2007; c. 2014; d. 2020. Source: Author, 2022. Datasource: Google Earth History 1996, 2002, 2014, 2020 accessed

2020, OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

5.2 Network Model 2: Gridded

Compartmentalization

By the 1990s, the Green Revolution

had established a comprehensive hydraulic irrigation system consisting of

canals, water channels, dikes, sluice gates, and pumps. Defined as a Grid

Network Model, Figure 8 shows an agrarian irrigation system composed of gridded

compartments, wherein a hierarchical system of primary and secondary canals was

devised. Canals and channels were incrementally added as part of a systematic

approach to optimize rice production. This system was enabled through the

drainage or irrigation of fresh water, based on the cultivation requirements of

different rice species. As a result, Figure 8 shows how the homogenous

irrigation system was formed by large-scale hydraulic systems, gridded across

the Delta region. The resulting water grid was driven by a hydraulic society

based on water control for land appropriation and cultivation purposes (Evers

and Benedikter 2009)

In contrast, extensive canals were introduced

during the French colonial period. Initial canals were dredged in Vinh Te, Ha

Tien, Rach Gia, and Long Xuyen, primarily for transportation and military

navigation purposes. While canals were not originally dredged for irrigation

purposes, technological advancements and the demand for flood and food security

shifted the focus of water management from navigation to water irrigation. This

transformation was achieved by extending existing canals and adding new

secondary ones, thereby creating a new water management approach in the

planning.

However, this shift failed to

reconsider the scalar gap between the industrial and local farming scale, as

recommended by the 1993 NEDECO Mekong Delta plan (NEDECO 1993). Investment in

the irrigation system neglected to integrate the water management system to

meet the needs of the farming unit. Consequently, the palimpsest mapping

reveals a large-scale homogenous system, a massive gridded system imposed over

the Delta’s original swamps. Moreover, the agrarian Grid network model reveals

how the entire territory has been appropriated for industrial-scale

agricultural development purposes. This high-level water grid was financed and

developed by the National Vietnamese government and mandated during Vietnam's

all rice production based on a water-oriented policy (Evers and Benedikter 2009).

Figure 8. Agrarian Gridded Compartments consisting of an extensive

irrigation system composed of rivers, canals and channels. Source: Author, 2022. Datasource: Google

Earth accessed 2019, OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

The basic mechanism for managing

water drainage and irrigation relies on the interplay between the wet and dry

seasons, along with the water and land requirements of the cultivated rice

species. For instance, as illustrated in Figure 9, during the wet season,

floodwaters draw water into the territory from the river channel and primary

canal feeders. If the inundation is too high, the sluice gates located at the

intersection of the primary and secondary canals can be manually closed to

prevent further water ingress. Moreover, raised dike systems along the canals

were designed to contain such wet-season inundations (elevated water levels)

and prevent overflowing into surrounding rice fields. These dikes were

typically raised between 1.5 to 3 meters or more, depending on the flooding

levels. Additionally, central pumping stations may be utilized to pump water

from secondary channels back to primary canals, effectively reversing the water

flow during floods. Individual farmers also used their pumps to direct water

according to their cultivation needs (Biggs 2012). Conversely, the water

irrigation system reverses during the dry season, when water is irrigated or

pumped into the fields. This process is enabled by the same pumping systems;

however, in this instance, the sluice gates may remain open, while certain

gates may be closed to divert water towards areas with higher water

requirements to meet specific irrigation needs.

Figure

9. Basic drainage water flow during wet season.

Source: Author, 2022. Datasource: Google Earth accessed

2019, OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

The farming scale, comprising houses

and associated gardens, had evolved from within the larger agrarian structure,

as mapped in Figure 10. Land parcels along the main canals were subdivided for

residential purposes, characterized by extended orchards interspersed within

elongated rice field sections. This landscape pattern has established a common

fabric language. Moreover, the linear settlements have valorized the dual dike

and road infrastructure developed along the primary canal with increased densification.

In addition to the original development along the canal fronts, they have

become even more intensified on the opposite side of the water, where new roads

were constructed. The comprehensive integration of houses, gardens, along

diked-road infrastructure running along the canal, constitutes the thickened

moment, thereby establishing Social Ecologies. These elements are the most

diverse and dynamic elements across the vast, homogenous agrarian fields

beyond.

Figure

10. Habitat and garden scale along the main canal, nested within the agrarian

structure. Source: Author, 2022. Datasource: Google Earth accessed 2019, OpenStreetMap, accessed

2019.

By the 2000s, larger-scale hydraulic

projects were managed through public-private partnerships to enhance irrigation

capacity from double to triple rice crops by further elevating the dikes. Their

project limits are shown in the gray zones in Figure 11. Not only do these

projects augment agricultural production, but they also provide flood

protection. For instance, after the 2010 flood, August dikes were proposed to

complete the irrigation system in An Giang province via planned hydraulic

project areas. These large-scale projects were invested in and managed through

public and private sector cooperation by centrally managed companies, such as

Joint Stock Construction Company No. 40 ICCO 40, and Joint Stock Dredging

Company No. II DRECO II (Benedikter 2014). They were mainly financed by

international organizations, including but not limited to Foreign Direct

Investments (FDI), Official Development Assistance (ODA), World Bank (WB), and

Asia Development Bank (ADB).

The foreign capitals mentioned above

provided aid or loans in response to the development market demands in the

Mekong Delta for various investments. These investments consequently

contributed significantly to the modernization of the Delta. Infrastructure

works encompassed water infrastructure, highways, roads, bridges, and other

works. Following the liberalization period, four major regional irrigation

projects were planned: Long Xuyen Quadrangle (our main study area), the Plain

of Reeds, the Trans-Bassac, and the Ca Mau Peninsula. These different projects

responded to different types of water ecosystems in the region. Hydraulic

projects and subprojects were subsequently planned accordingly, resulting in an

increasingly complex system of canals with associated irrigation channels,

dikes, embankments, sluice gates, and pumping stations. (Benedikter 2014)

The main irrigation projects located

within our Long Xuyen Quadrangle and Can Tho study area include Vinh Te, Cai

San, and O Mon-Xa No Canal, which have been under development for over two

decades. Within the regional Long Xuyen Quadrangle hydraulic project area, the

rapid extension of existing and construction of new dikes in the historical

floodplains has transformed An Giang province into a network of irrigated

fields, thereby safeguarding floodwaters from entering the fields during the wet

season.

Figure 11. Large-scale hydraulic projects are set as rice

intensification zones found within the gridded agrarian landscape, as shown in

gray. Source: Author, 2022.

Source: Dike routes and diked areas in the Mekong

Delta (Dat 2013) taken from (Nguyen 2015). Datasource: GIS Geodata GMS 2019.

Google Earth accessed 2019, OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

5.3 Network Model 3: Hybrid

Urban-Rural Diffusion

Defined as a Hybrid Network Model, these

hybrid zones appear to span between urban-rural infrastructure as blue-green corridors,

as mapped out in green in Figure 12. These corridors are composed of a more

organic fabric, contrasting with the previous Grids Network Model. Within this mixed

area, local activities appear to valorize the combination of natural

environments and irrigation systems for habitat and cultivation purposes. A

diversified landscape characterizes the vast areas of upland crops, which appear

to extend into the agricultural fields.

These diverse landscapes were

predicated on the compatibility of cultivation practices with soil types and the

type of water infrastructure available. Historically, the planting of different

fruit trees was guided by principles of organic agriculture, which were

inherent in the local ecological wisdom of farmers across generations.

Ecological wisdom encompasses the deep understanding of the Delta’s natural ecosystem

processes. Over time, local cultivation knowledge discovered methods of

optimizing the constructed drainage and irrigation system by integrating ecosystem

processes. Through this local practice, crop varieties were meticulously

selected between perennial, annual, and short-term crops. Different species of

crops were rotated based on their environmental compatibility and their monetary

value in local markets.

In particular, this hybrid zone

includes an orchard-based landscape characterized by human settlements that

subsist on the dike system along rivers or canals. These waterfront settlements

are mainly engaged in garden cultivation of upland crops, annual crops, and

various aquaculture. They appear to be concentrated in more protected areas

within the topographically elevated ground along the Bassac River's natural

levee and its main tributaries. This hybrid area spans approximately 6 to 12km

from the river. However, these hybrid zones also emerge around the peri-urban

areas surrounding main cities such as Can Tho, and along artificially elevated

areas, constructed from the resulting mounds left over from the dredging of

canals.

Figure

12. Map showing the hybrid zones of mixed crop cultivation (in green), mainly

in orchards, upland crops, annual crops, and fish farms. These zones appear to

be coupled with intensified urban areas located along the river, in this case,

Long Xuyen City (left) and Can Tho City (right).

Source: Author, 2022. Datasource: Google Earth accessed

2020, OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

A detailed examination of the

zoomed-in hybrid zone is shown in Figure 13, which reveals the dual function of

the diked road network as residential access and blue-green infrastructure for

orchard cultivation. Thickened moments of linear urban settlements appear on

both sides of the road, concurrently paired with extensions of diversified

orchard and fruit tree plantations that extend into the agricultural fields. This

suggests the establishment of micro-economic activities that benefit from the

protected elevated areas along the canal embankments. In contrast, less

intensive settlements and orchard areas reside along tertiary streams due to

the limited supporting infrastructure available in these areas.

Figure 13. Map showing a detailed area illustrated by the organic

growth in the hybrid model, characterized by the densification of settlements

along diked road networks with large extensions of orchard cultivation areas. Source: Author, 2022. Datasource: Google

Earth accessed 2020, OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

Figure 14 explains the rationale

behind the evolution of development along the canal, as depicted in the

following section. The initially colonized land, which emerged from the

dredging of the canals, subsequently created a natural protective layer along

the canal embankments. This layer, composed of leftover sand from the dredging,

created raised beds that attracted informal stilt housing settlements. The

subsequent intensification of rice cultivation in the fields beyond led to the

introduction of diked embankments directly behind these stilt houses, thereby

creating an irrigation system. This, in turn, attracted land-based houses on

the opposite side of the water, resulting in ad hoc property development there.

These mixed-use houses consisted of elevated land beds for habitation purposes

with shopfronts on the ground, which were further enhanced with orchard

plantations. All these new additions benefited from protection from floods and

access to new networks that connected to other destinations.

Figure 14. Section

showing the upgrade from river stilt housing development along a natural levee

to an embankment raised by dikes on both sides, further constructed as road

access. On the land side of the roads, new modern shophouses were constructed

with raised orchard beds. Elaborated by author.

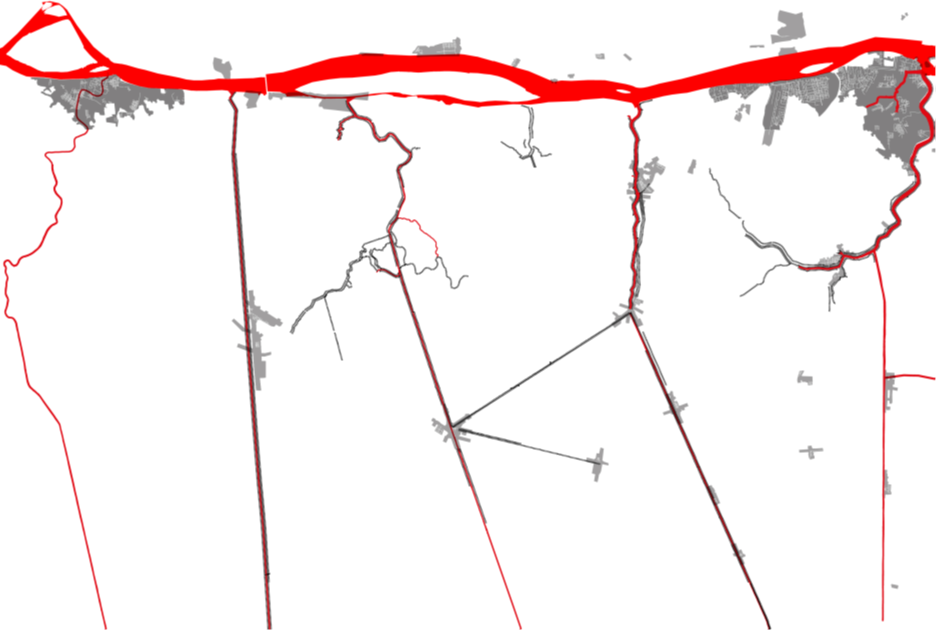

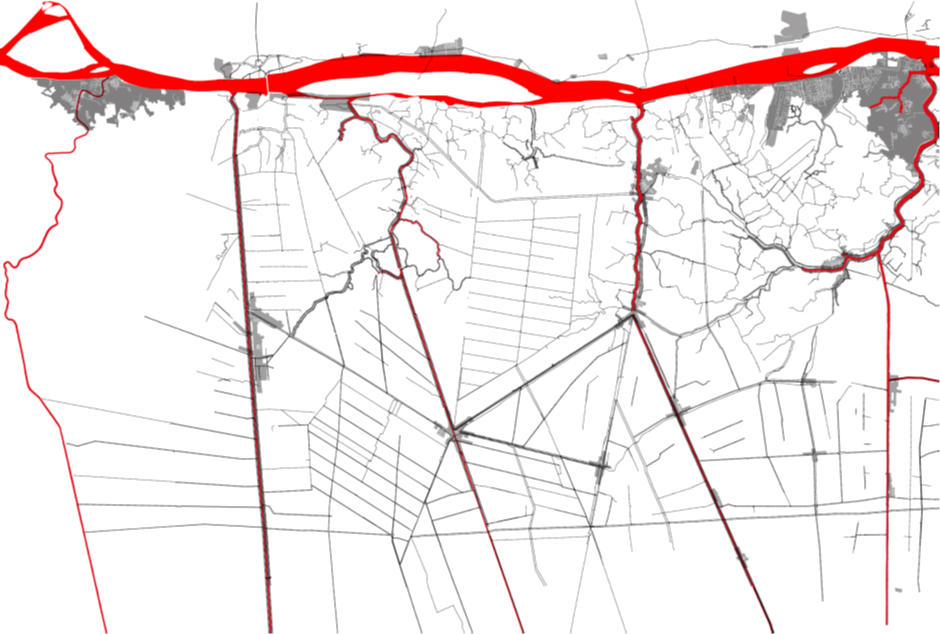

Figure 15 presents a comprehensive

Palimpsest map of all the Network Models that constitute the study area’s

landscape pattern, in the Mekong Delta. It depicts the interconnected layers as

complex systems and subsystems of the Star, Grid, and Hybrid Network Models.

This palimpsest map comprises all the layers presented before, including the

French colonial canal layers, the hydraulic projects, urbanization patterns,

and diversified Social Ecological landscapes. All these overlapping layers

illuminate the different processes and agencies that have shaped the territory.

These forces driving the Delta are influenced by various powerful agencies that

control water resources. These agencies engage in a dynamic interaction that

"compete, superimpose, and react" as described by Boelen et al.

(2016) as Hydro-Social Territories. Territorial transformations emerging from

overlapping hydrological projects, informal economic activities, and growth

across the urban-rural milieu, and increasingly heterogeneous land cover, have

led to complex interactions. Paradoxically, the Delta’s water ecosystem

services have enabled the very territorial transformations that have

subsequently threatened its natural resources. As defined by Boelen, these

types of hybrid zones undergo constant modification and reorganization across

the territory through the competing actions taken across multiple actors,

actants, and at different scales.

Figure

15. Map showing how overlapping these layers, including French colonial canals,

systems of hydraulic projects, urbanization patterns, and diverse landscapes. Source: Author, 2022. Source: Dike routes and diked areas in the Mekong Delta (Dat, 2013)

taken from (Nguyen, 2015) Datasources: GIS Geodata GMS 2019. Google Earth

accessed 2019, OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

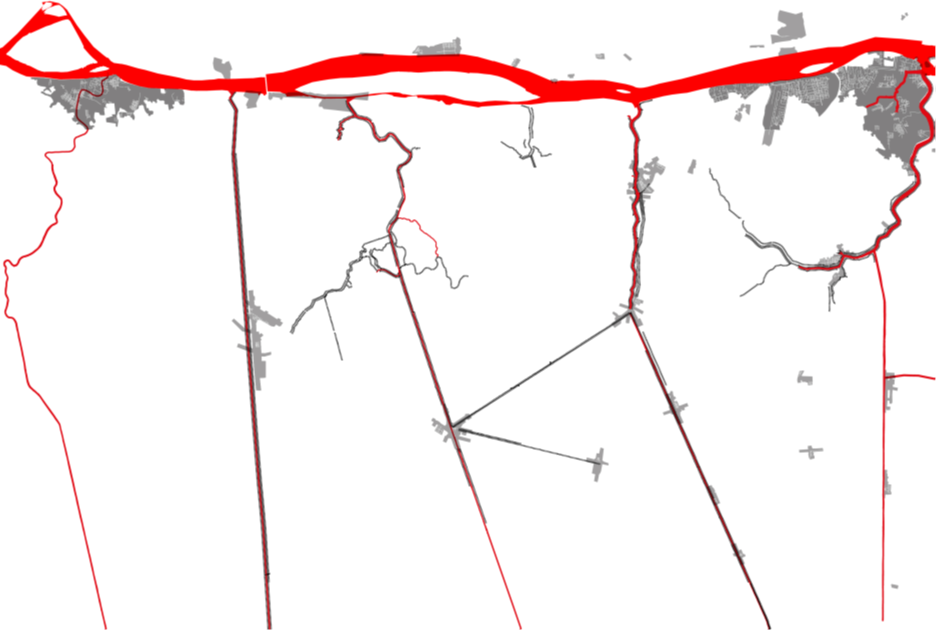

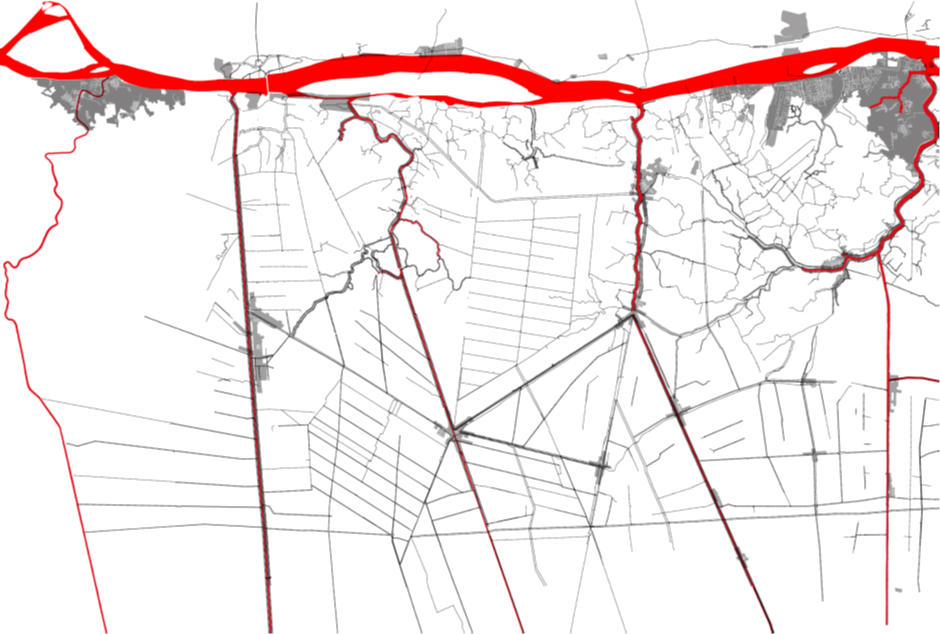

Figure 16 shows a more detailed study

area, whereby the identified Network Models of Stars, Grids, and Hybrids were

found to overlap. These overlapping patterns signify the intricate interactions

generated between the top-down managerial operational processes and the

bottom-up local responses to novel resources. The study area has been framed to

clarify the geographic relationship as a Transect. This Transect study (drawn

from left to right) commences from the primary River branch originating from

the Mekong River to the left, proceeds to the natural levee (which spans about

10-15 km), and transitions from the upper alluvial to the lower alluvial plain.

These geographical features provide insights into the locations and utilization

of natural water ecosystems across the Transect.

Figure 16 illustrates how the

phenomenon is driven by the Star Network Model configuration, which is

identified to the right where three major canals intersect. The Omon Town

Channel and Vertical canals converge at the focal point where Thoa Lai Town

center was established. These canals radiate outwards into branches of water

channels, serving as water traffic routes between town centers, approximately 15km

apart. Further along the Omon River, an intricate relationship exists between

the formerly channeled Omon River and a constructed highway (QT922). Whereby

layers of linear Desakota-driven settlement have extended between Omon Town and

Thao Lai Town, connected by the river-highway corridor. This growth pattern encompasses

urbanization and industrial activities that have progressively densified along

the parallel highway connecting the two towns.

Concurrently, the map in Figure 16 illustrates

how the Grid Network Model was formed through the implementation of red

irrigation networks by the Hydraulic Society to promote rice production. These

layers of irrigation channels were superimposed upon the original canals and

watercourses. They were integrated with high dikes (complete with road), strategically

elevated above the flood levels of primary canals and streams. This approach

served as a top-down mechanism to shift the rice cultivation capacity from double

to triple annual harvests.

Conversely, the mixed zones

represented in gray by the Hybrid network model show a propensity for Social

Ecological resilience. This extended gray zone merges the characteristics found

in the other two Network Models. It incorporates the linear settlement pattern

found in Desakota and the valorization of the water networks, which were developed

through the irrigation system. All these elements are intricately combined to

create a mixed-use Hybrid zone. This hybrid zone comprises orchards, family

farming units, and other activities such as shopfronts and aquaculture. It

demonstrates a bottom-up dynamic response to the top-down infrastructural

construction plans. This resilient potential highlights the ability for Hybrid

Network Models to bridge the resources generated from top-down processes with

the local knowledge derived from bottom-up approaches. Which emerges as novel

Social Ecologies with the potential to reframe the challenges inherent in

anthropogenic processes.

Fig. 16. Map of the study area in O Mon and Thoa Lai district, showing the

complex relationship resulting in the overlapping phenomena identified in the

Star, Grid, and Hybrid network models. Elaborated by author. Sources “The

relation between land use and subsidence in the Vietnamese Mekong delta,” GIS

Land Use 2009, Courtesy of (Minderhoud et al. 2018). Datasources: GIS Geodata

GMS 2019. Google Earth accessed 2020, OpenStreetMap, accessed 2019.

6. Discussion 1: STAR Network

Model

The findings from the initial

palimpsest mapping conducted in the Star Network Model underscore the

imperative for further investigation into the accelerated Anthropogenic impact.

Primarily due to the ad hoc linear development activities prevalent across

urban and rural linkages. The identified rapid linear settlement pattern along

water canals and associated roads has indirectly catalyzed artificial

transformations by exerting strain on existing infrastructure. This subsequent

growth was recognized as a Desakota phenomenon, represented by the ad hoc

bottom-up response to water management and infrastructural investment.

Paradoxically, the local farmers’

original “living with the water” paradigm was challenged by the introduction of

diked roads. Thereafter, these road networks attracted Desakota activities,

which rapidly intensified. This inversion, from a history of

waterfront-oriented activities in harmony with the water ecosystem, to

land-based activities turned away from the rivers and canals, resulted in the capitalized

use of land appropriation. Consequently, these activities have become

increasingly alienated from the water system. This phenomenon is exacerbated by

the peri-urban densification, which relies on the installation of flood defense

infrastructure and significant land alterations.

The Desakota culture represents a

glocalized response to the interplay between top-down and bottom-up

urbanization and industrialization processes. This mainly manifests along the

main road and water infrastructure, facilitating communication between urban

and rural areas. Actors leveraging road-based infrastructure gain access to

urban activities through investments made in commerce, services, real estate

development, and industry. These Desakota-oriented endeavors involve shop

owners, families residing in shop houses, traders from designated open markets

at designated centers, and real estate developers. Furthermore, larger

operations drawn by investment in water and road infrastructure include

production-based industries, primarily focused on rice processing, gravel,

sand, and minerals resource extraction, and the transportation or trade of

agricultural yields and construction materials.

The Desakota situation essentially

exploits the interaction between nature and the built systems to support

livelihoods (Desakota Study Team, 2008). Desakota's growth has subsequently

intensified linear urbanization and industrial activities across road networks

between town centers, significantly altering the original land and imposing

environmental strain. The process of building land intensification entails

transforming the land from its natural soil state into compressed soils or

asphalt-covered areas to support building foundations. This, coupled with

densified urban areas, necessitates the provision of fresh water, which is

often extracted through the exploitation of groundwater, leading to land

subsidence (Minderhoud et al. 2018). Moreover, polluted stormwater runoff from

impermeable paved surfaces in urban areas is discharged into designated ground

drainage. Many of these systems release the water back into rivers without

undergoing any treatment, thereby polluting the water and further hindering the

replenishment of groundwater.

7. Discussion 2: GRIDDED Network

Model

Powerful Hydro-politics in the Delta

have shaped the formation of an irrigated land pattern, identified as the Grid

Network Model. The establishment of the Delta-wide canalized water management

system was meticulously funded through agencies in water technological and managerial

operations. Consequently, the water control mechanism facilitated the manipulation

of the Delta into productive agrarian landscapes. These mechanisms were further

enhanced by substantial investment and implementation of numerous large-scale

hydraulic project zones, strategically distributed across the Mekong Delta.

The amalgamation of numerous

hydraulic irrigation projects has shrunken the Delta’s natural watershed by

diverting flood waters into unforeseen areas. These hydraulic interventions have

raised water levels and shortened the inundation period, occasionally diverting

water to vulnerable urban districts such as Can Tho City and Long Xuyen City. A

series of detrimental cycles of anthropogenic impacts also proceed flood

diversion: Previous swamp land prepared for rice production becomes irrigated

land, rendering it incapable of self-cleansing during the flooding season. Consequently,

the soil remains with heightened levels of acidification and a lack of

nutrients due to the absence of sedimentation. Subsequently, necessitating an

increased utilization of chemical treatment due to infertile (acidic) soils,

which, in turn, contributes to water pollution and biodiversity decline.

Planning tools associated with the

implementation of water management policies have transformed the delta’s

floodplains and landscape into a matrix of grid-based agricultural

compartments. These land modifications have introduced another rationality, as

a substantial structure has been superimposed upon the Delta's water

ecosystems. These gridded structures have consequently and inadvertently

obliterated the inherent resilience of the Delta's self-regenerating

floodplains and associated water ecosystem processes.

Lastly, the zoning of the Delta into

agricultural, industrial, and urban areas, as a planning tool focused on

monofunctional land-use planning, has fragmented its natural geomorphology.

Furthermore, as a planning approach based on monetary values, this type of land

appropriation and preparation primarily relies on setting boundaries. As a land

management approach that values land certainty and security, determined by its

monetary yields defined by its land parcelization type, it is unsurprising that

this approach contradicts the Delta's natural cyclical processes. As an

economic land management approach, the Delta management plan completely

overlooks the Delta’s fluid water ecosystems processes, whereby space and time

continuously flow and change with the wet and dry seasons.

8. Discussion

3: HYBRID Network Model & paradigm shift

The palimpsest findings of the Hybrid

Network Model offer a glimpse into the concept of ‘reversing the code.’ This

approach involves a bottom-up process that leverages existing water ecosystems

while simultaneously capitalizing on the top-down investments in irrigation

infrastructure. Unlike the other two models, which result in the further

exploitation of the Delta’s altered water system—Grids through irrigation and

Stars through Desakota—the Hybrid model provides mutual benefits to the Delta, leading

to enhanced landscape diversification. This factor contributes to a more

resilient response to the global economic and industrial forces at play. The

Hybrid Network Model effectively leverages the new infrastructure with existing

ecosystems to produce mutually advantageous combinations of landscapes.

Emerging as a Hybrid Network Model, the

blue-green corridors with extended gardens appear to encroach upon the

agricultural fields. These corridors comprise an interwoven dynamic of

cultivated landscapes and built constructs, where work and living typologies

are adopted. The subsequent local response to large-scale infrastructural

investments involving dikes doubled down as roads, is to harness it into the

locality through small, ad hoc interventions that safeguard habitats

(flood-protected dwellings) and facilitate micro-economies in garden

cultivation. Many of these gardens stem from the waterways and extend into the

agricultural fields, comprising a diverse array of orchards, shrimp ponds,

vegetation, and farm animals.

The resulting hegemonic structure is hypothesized

to be an evolutionary component of the Desakota phenomenon (from the Star

Network Model), with more relevance to local knowledge regarding ecological

wisdom. In addition to farming industries that have profited from the

infrastructural investments made for agriculture, Desakota activities have also

benefited from the transformed water-road networks of the Delta. Furthermore, local

farmers utilized access to network systems to support their farming micro-markets

by cultivating more varieties of crops based on land compatibility. This has resulted

in the interplay between the provision of ecosystem services (soil, fertile

ground, irrigation) and infrastructural capacity (water, sewage, energy).

Although this provision can impose

additional pressure on the territory, possibly leading to anthropogenic impacts,

the intensification between urban and rural linkages across diversified

blue-green corridors holds the potential to transform the currently homogenous fields

into ecologically resilient territories. The Mekong Delta's territorial

relationship between the water channels, urban centers, and land networks presents

an opportunity to adopt new approaches that foster Social Ecological resilience.

Resilience that integrates the water processes, interactions between

institutions involved in water and landscape management, socio-economic interactions

between farmers and traders, various industrial practices in land cultivation

for food production, and more rural-urban drivers. For these reasons, the

research raises the following question:

How can lessons learned in the

Hybrid Network Model inform the redesign of various hydraulic projects, hybrid

land mosaics, and rururban Desakota patterns, to create space for a more Social

Ecologically resilient Delta in confronting the water ecosystem threats in the

Mekong Delta?

9. Discussion 4: The Evolution of

Hybrid Models

The Mekong Delta has entered the

Anthropocene due to the compounded effects of water control enabled by water

management of hydraulic infrastructure, resource exploitation, and intense

land-altering development processes. In response, local farmers and settlements

have further exploited the transformed land, with their agenda for ensuring the

combination of habitat and micro-economies, through live-work garden and pond

cultivation patterns, unintentionally exacerbating the altered state of the

Delta.

The palimpsest study has elucidated

the evolution of three major Network Models over the past decades.

Demonstrating how these models have progressively transformed into increasingly

complex systems and subsystems, albeit inadvertently contributing to the

anthropogenic state. Territorially, the Network Models discovered in Stars,

Grids, and Hybrid patterns exhibit a complex set of dynamics distinguished by

the interaction between local and global driving forces. The palimpsest research

finds that these dynamic fabric patterns have consequently transformed into Social

Ecological combinations. As new combinations, these heterogeneous

configurations are characterized as hegemonic fabric patterns formed over

periods, by various driving forces, all leading to intricate territorial

(re)configurations.

These configurations can either

create more integrated or fragmented relationships across the urban-rural

fabric. When fragmentation occurs, it often reveals a spatial mismatch and a

scalar gap in land-use planning, hydraulic management, and land ownership

patterns. The reconfiguration of deltaic land, particularly to support

intensified zones of agrarian production and urbanization, has exacerbated

environmental impacts, including flooding, salination, erosion, water

pollution, and other factors. Although territorially productive under their

respective agenda, the combination of these models has also contributed to the

environmental challenges faced by the transformed state of nature.

10. The findings in the Hybrid

Model call for a paradigm shift

In contrast to the other two Network

models, the Hybrid Network Model demonstrates resilient Social Ecological

processes that have the potential to reverse the code resulting in

anthropogenic outcomes, thereby illuminating the pathway toward an Ecological

Transition. Reversing the code can be achieved through the progressive

ecological diversification of land and its integration into farmers’ processes

and livelihoods. As illustrated in the section depicted in Figure 15, the

incremental transformation of land from the local utilization of gray

infrastructure networks, in combination with associated dwellings and

cultivated gardens, serves as evidence of beneficial Social Ecological

interactions.

This hybridization of processes,

encompassing the combination of blue-green infrastructure, the Desakota

colonization dynamic, and the diversification of landscape cultivation,

demonstrates existing resilience that remains untapped. This untouched informal

procedure should be integrated into the Delta’s formal territorial planning

process. The resilient land diversification patterns exhibited by the Hybrid

Model necessitate a paradigm shift to further foster the diverse state of

hybrid combinations, regarded as Social Ecologies. By mutually

benefiting rather than exploiting the Mekong Delta’s landscape and water ecosystems,

the Hybrid Model may further develop a multitude of landscape and ecological

combinations and cultivation processes.

Consequently, to work harmoniously

with the Mekong Delta’s ecosystems, a new perspective must be fostered. Instead

of solely focusing on the many agencies that have transformed it over time, we

must post-rationalize the Delta’s natural states and its altered states. To

recognize the Mekong Delta as a ‘terrestrial constituent’ (Bruno Latour 2018)

and agency of change, we must shift the focus from utilizing the Mekong Delta

solely for ecosystem services. Rather than becoming an object of

commodity in ecosystem services, the Delta transforms into a territorial subject

through which to redefine climate change thresholds and promote Social

Ecological resilience. As a social production of material culture, the Delta

equally reacts to climate change’s impact on humans and nonhumans alike.

Therefore, the Mekong Delta’s Water as Subject paradigm shift will

elevate it to an equal territorial actor and participant in the ongoing

discourse of Social Ecological progress (Vigano 2022, Vigano et al. 2023). The

Mekong Delta shall ultimately serve as a catalyst, paving the way for valuable

lessons, informing novel water ecosystem processes, and reframing the climate

change phenomenon towards an Ecological Transition.

11. Concluding Remarks: The urgent

need for restructuring anthropogenic processes identified in the three Network

Models

The three Network Models were shaped

by anthropogenic processes that transformed the Mekong Delta’s estuary characteristics.

The construction of extensive hydraulic works accelerated environmental

degradation by precisely controlling water flow, direction, and quantity through

water pumps, sluice gates, and dikes. This subsequently affected the Delta’s water

and soil quality. Anthropogenic processes began with the division of

floodplains into water management units and the appropriation of swampland for

agriculture. Powerful state actors and private organizations driven by agrarian

production-oriented water policy invested in the agricultural sector. Furthermore,

engineered water techno-managerial projects associated with irrigation were

incrementally planned and constructed, with progressively larger-scale water

works. Lastly, local responses leveraged access to new infrastructure with

natural resources through different land appropriation and cultivation practices.

The palimpsest analysis findings delineate

Grids, Stars, and Hybrid Network Models, thereby answering the research

question regarding territorial configurations resulting from human-induced

processes across the Mekong Delta and the agencies behind them. The Star

Network Model unveils a radial pattern of linear growth along intersecting waterways,

resulting in urban-rural development patterns characterized by Desakota, as intensified

linear settlement development along key infrastructure. This phenomenon shifts

away from the “living with the water” paradigm by capitalizing on land-based

driven densification along network infrastructure. Financed by influential

Hydro-political actors, the Grid Network Model presents large-scale hydraulic

infrastructural networks superimposed in a gridded pattern. Facilitated by advancements

in water technological and managerial procedures, the resulting agrarian

irrigation systems enabled substantial agricultural production. Consequently,

diverting the Delta’s natural flooding patterns hinders the Delta from its self-regenerative

processes. The first two dynamic Network Models emerged from general forces,

the interplay between top-down and bottom-up processes. These interactions generated

territorial dynamics in favor of Hydrological constructs, contradicting the

laws of nature and inadvertently erasing the Delta’s natural states. However, the

Social Ecological resilience emerges from the identified Hybrid Network Model,

which challenges these Hydro-political processes, revealing overlapping patterns

of dynamic Social Ecological resilience. By reversing the code wherein a more

mutual interrelationship is formed between nature and humans, the pattern of blue-green

corridors integrated with productive habitats signifies a shift towards

rethinking the relationship between anthropogenic and natural processes. Therefore,

the Hybrid Network Model’s combination of landscape and built systems presents

an opportunity for Social Ecological Resilience. This proposed paradigm shift, characterized

by the reframing of Water as Subject, transforms the Mekong Delta’s water

ecosystem as agency, thereby facilitating a resilient Ecological Transition.

Interest is taken in the

countercurrent process between top-down and bottom-up forces, as Desakota

coupled with blue-green ecological systems evolve into increasingly hybrid and

heterotopic forms and processes, representing an evolution of Social Ecological

resilience. The central question now revolves around how these actors will

collaborate within this Hybrid Network Model and 'reverse the codes.' Which

entails the reversing of the current exploitation of the Mekong's water

territory into ecosystem services by approaching the Delta’s resilience through

the integration of its inherent ecological values with novel Social Ecologies.

The research findings provide design research recommendations to address the

subsequent question: how can reframing hydraulic projects, hybrid

landscapes, and rururban patterns generate space for a more Social-Ecologically

resilient system in facing the water ecosystem threats in the Mekong Delta?

12.

References

Barcelloni,

Martina Corte, and Paola Viganò, eds. 2022. The Horizontal Metropolis: The

Anthology. Cham: Springer.

Benedikter,

Simon. 2014. “Extending the Hydraulic Paradigm: Reunification, State

Consolidation, and Water Control in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta after 1975.” Center

for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University. https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.3.3_547.

Biggs,

David. 2010. Quagmire: Nation-Building and Nature in the Mekong Delta.

Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Biggs,

David. 2012. “Small Machines in the Garden: Everyday Technology and Revolution

in the Mekong Delta.” Modern Asian Studies 46 (1): 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X11000564.

Biggs,

David, Fiona Miller, Chu Thai Hoanh, and François Molle. 2009. “The Delta

Machine: Water Management in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta in Historical and

Contemporary Perspectives.” In Contested Waterscapes in the Mekong Region:

Hydropower, Livelihoods, and Governance, 203–25. 1st ed. USA: Routledge.

Boelens,

Rutgerd, Jaime Hoogesteger, Erik Swyngedouw, Jeroen Vos, and Philippus Wester.

2016. “Hydrosocial Territories: A Political Ecology Perspective.” Water

International 41 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2016.1134898.

Brocheux,

Pierre. 1995. The Mekong Delta: Ecology, Economy, and Revolution, 1860–1960.

Monograph / University of Wisconsin-Madison. Center for Southeast Asian

Studies, no. 12. Madison, WI: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, University of

Wisconsin-Madison.

Corboz,

André. 1983. “The Land as Palimpsest.” Diogenes 31 (121): 12–34.

De

Meulder, Bruno, and Kelly Shannon. 2018. “The Mekong Delta: A Coastal

Quagmire.” In Sustainable Coastal Design and Planning. Boca Raton, FL:

Taylor & Francis.

Edmonds,

D. A., R. L. Caldwell, E. S. Brondizio, and S. M. Siani. 2020. “Coastal

Flooding Will Disproportionately Impact People on River Deltas.” Nature

Communications 11 (1): 4741.

Ehlert,

Judith. 2012. Beautiful Floods: Environmental Knowledge and Agrarian Change

in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. ZEF Development Studies, v. 19. Berlin: Lit.

Eslami,

S., P. Hoekstra, N. Nguyen Trung, S. Ahmed Kantoush, D. Van Binh, D. Duc Dung,

and M. van der Vegt. 2019. “Tidal Amplification and Salt Intrusion in the

Mekong Delta Driven by Anthropogenic Sediment Starvation.” Scientific

Reports 9 (1): 18746.

Eslami,

S., P. Hoekstra, P. S. Minderhoud, N. N. Trung, J. M. Hoch, E. H. Sutanudjaja,

and M. van der Vegt. 2021. “Projections of Salt Intrusion in a Mega-Delta under

Climatic and Anthropogenic Stressors.” Communications Earth &

Environment 2 (1): 142.

Evers,

Hans-Dieter, and Simon Benedikter. 2009. “Strategic Group Formation in the

Mekong Delta: The Development of a Modern Hydraulic Society.” Bonn: Department

of Political and Cultural Change, Center for Development Research, University

of Bonn.

Ginsburg,

Norton Sydney, Bruce Koppel, T. G. McGee, and East-West Environment and Policy

Institute (Honolulu, Hawaii), eds. 1991. The Extended Metropolis: Settlement

Transition in Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Kondolf,

G. M., R. J. Schmitt, P. Carling, S. Darby, M. Arias, S. Bizzi, and T. Wild.

2018. “Changing Sediment Budget of the Mekong: Cumulative Threats and

Management Strategies for a Large River Basin.” Science of the Total

Environment 625: 114–34.

Latour,

Bruno. 2018. Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. John

Wiley & Sons.

Lawson,

Gillian, Mirko Guaralda, and Phuong Nga Nguyen. 2022. “Water Urbanism and

‘Living with Flooding’: A Case Study in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam.” Housing

and Society 49 (2): 150–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2021.1978041.

Le Coq,

J. F., G. Trébuil, and M. Dufumier. 2004. “History of Rice Production in the

Mekong Delta.” In Smallholders and Stockbreeders, edited by P. Boomgaard

and David E. F. Henley, 163–85. BRILL. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004487710_009.

Liao,

Kuei-Hsien, Tuan Anh Le, and Kien Van Nguyen. 2016.

“Urban Design Principles for Flood Resilience: Learning from the Ecological

Wisdom of Living with Floods in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta.” Landscape and

Urban Planning 155 (November): 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.01.014.

McGee,

Terry. 2009. “The Spatiality of Urbanization: The Policy Challenges of

Mega-Urban and Desakota Regions of Southeast Asia.” UNU-IAS Working Paper

No. 161. Vancouver: University of British Columbia.

Minderhoud,

P. S., G. Erkens, V. H. Pham, V. T. Bui, L. Erban, H. Kooi, and E. Stouthamer.

2017. “Impacts of 25 Years of Groundwater Extraction on Subsidence in the

Mekong Delta, Vietnam.” Environmental Research Letters 12 (6): 064006.

Minderhoud,

P. S. J., L. Coumou, L. E. Erban, H. Middelkoop, E. Stouthamer, and E. A.

Addink. 2018. “The Relation between Land Use and Subsidence in the Vietnamese

Mekong Delta.” Science of the Total Environment 634 (September): 715–26.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.372.

Minderhoud,

P. S. J., H. Middelkoop, G. Erkens, and E. Stouthamer. 2020. “Groundwater

Extraction May Drown Mega-Delta: Projections of Extraction-Induced Subsidence

and Elevation of the Mekong Delta for the 21st Century.” Environmental

Research Communications 2 (1): 011005.

Minkman,

Ellen, Arwin van Buuren, and Victor Bekkers. 2021. “Un-Dutching the Delta

Approach: Network Management and Policy Translation for Effective Policy

Transfer.” International Review of Public Policy 3 (2): 172–93. https://doi.org/10.4000/irpp.2174.

NEDECO,

M. 1993. Master Plan for the Mekong Delta in Viet Nam: A Perspective for

Sustainable Development of Land and Water Resources. Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam:

Netherlands Engineering Consultants.

Nguyen,

Phuong Nga. 2015. Deltaic Urbanism for Living with Flooding in Southern

Vietnam. PhD diss., Queensland University of Technology.

Rowe,

Colin, and Fred Koetter. 1978. Collage City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schmitt,

R. J. P., and P. S. J. Minderhoud. 2023. “Data, Knowledge, and Modeling

Challenges for Science-Informed Management of River Deltas.” One Earth 6

(3): 216–35.

Scown,

M. W., F. E. Dunn, S. C. Dekker, D. P. van Vuuren, S. Karabil, E. H.

Sutanudjaja, and H. Middelkoop. 2023. “Global Change Scenarios in Coastal River

Deltas and Their Sustainable Development Implications.” Global Environmental

Change 82: 102736.

Shane,

David Grahame. 2005. Recombinant Urbanism: Conceptual Modelling in

Architecture, Urban Design, and City Theory. Great Britain: Wiley-Academy.

Shane,

David Grahame. 2021. “Urban Design in the Anthropocene.” In Metropolitan

Landscapes, edited by Antonella Contin, 28: 67–80. Landscape Series. Cham:

Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74424-3_4.

Shannon,

Kelly, and Bruno De Meulder. 2012. “Water Urbanism.” Topos, no. 81:

24–31.

Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

2013. Mekong Delta Plan: Long-Term Vision and Strategy for a Safe,

Prosperous and Sustainable Delta. Royal HaskoningDHV in collaboration with

the Vietnamese Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI), Deutsche Gesellschaft

fur internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), Wageningen University Research (WUR),

and Deltares Rebel.

Socialist Republic of Vietnam

and the Kingdom of the Netherlands. 2020. Mekong Delta regional integrated