Proposal for the Design of Cultural Tourist Routes through the Use of GIS: An Applied Case

Propuesta de Diseño de Rutas Turístico-Culturales mediante el Empleo de SIG: Un Caso Aplicado

Diego Manuel Calderón-Puerta

diego.calderonpu@alum.uca.es  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9131-9812

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9131-9812

Manuel Arcila-Garrido

manuel.arcila@uca.es  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9724-3767

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9724-3767

Departamento de Historia, Geografía y Filosofía. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras.

Universidad de Cádiz. Avda. Doctor Gómez Ulla, s/n. 1, 11003 Cádiz

INFO ARTÍCULO

Enviado: 08-05-2019

Revisado: 24-01-2019

Aceptado: 27-01-2019

KEYWORDS

Geographic Information System

Tourism Potential

Tourist Route

Heritage

Late Middle Age

ABSTRACT

Cultural tourism routes and itineraries are tourism promotion tools that have undergone a remarkable development in recent years, thanks to their ability to enhance the value of cultural heritage. In this sense, national and international organizations as well as private initiatives have designed tourist routes that cover a wide range of topics, while cultural itineraries have been recognized at the institutional level by organizations such as ICOMOS or the Council of Europe.

The main objective of this article is to offer a proposal for the design of cultural tourist routes through the use of a geographic information system. To achieve this goal, we start from a brief theoretical framework in which the tourist use of geographic information systems and the conceptualization of tourist routes and their differences with itineraries are analyzed. Subsequently, the methodology used consists of two distinct phases. Initially, a quantitative study is carried out in which data on the late medieval heritage are collected and subsequently, through the use of a GIS, an index of tourist potentiality is carried out and the creation of a tourist route in the province of Cádiz (Spain). In this way the results obtained justify the route designed and the choice of municipalities, based on their greater availability of tourism resources (accessibility, hospitality etc.) and cultural (historical assets).

With all this is intended the activation of a heritage that has notorious possibilities for tourism and cultural promotion, based on the common history they share and that is forged over more than two centuries.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Sistema de Información Geográfica

Potencial Turístico

Ruta Turística

Patrimonio

Baja Edad Media

RESUMEN

Las rutas y los itinerarios de turismo cultural son herramientas de promoción turística que han experimentado un notable desarrollo en los últimos años, gracias a su capacidad para aumentar el valor del patrimonio cultural. En este sentido, las organizaciones nacionales e internacionales, así como las iniciativas privadas, han diseñado rutas turísticas que cubren una amplia gama de temas, mientras que los itinerarios culturales han sido reconocidos a nivel institucional por organizaciones como el ICOMOS o el Consejo de Europa.

El principal objetivo de este artículo es ofrecer una propuesta de diseño de rutas turisticas culturales mediante el uso de un sistema de información geográfica. Para alcanzar este fin, partimos de un breve marco teórico en el que se analiza el uso turistico de los sistemas de información geográfica y la conceptualización de las rutas turísticas y sus diferencias con los itinerarios. Con posterioridad, la metodología empleada consta de dos fases bien diferenciadas. En un primer momento, se hace un estudio cuantitativo en el que se recopilan datos sobre el patrimonio bajomedieval y posteriormente, mediante el uso de un SIG, se lleva a cabo un índice de potencialidad turística y la creación de una ruta turística en la provincia de Cádiz (España).

Con todo esto se pretende la activación de un patrimonio que tiene notorias posibilidades para el turismo y la promoción cultural, basado en la historia común que comparten y que se ha forjado durante más de dos siglos.

1. INTRODUCTION

Cultural tourism routes are currently presented as one of the most popular means of disseminating historical heritage. In Spain, except for some initiatives such as the routes of war promoted at the end of the civil war, the use of these tourist resources takes place in a generalized manner in the 1960s (Pack, 2006). With the recognition of the cultural itineraries initiated in 1987 with the declaration of the Camino de Santiago, an extensive bibliography (Parrado del Olmo, 2003; López, 2006; Moreré, 2009; Hernández, 2011; Navalón, 2014, Calderón, Arcila and López Sánchez, 2018) is generated that analyzes the concept of routes and itineraries treating them as well as two synonyms or different but complementary realities.

Geographic information systems as multidisciplinary tools have a notorious influence on tourism studies given the capabilities they offer for the analysis and interrelation of variables (Nieto Masot, 2018, pp 39-55). For this reason, considering its application to the creation of a methodology in the creation of tourist routes is of essential importance for the proposal of itineraries that are supported by a detailed study of heritage, tourism resources, accessibility or demand.

It is based on the hypothesis that the majority of existing tourist routes do not count in their design and definition with a contrasted methodology. Moreover, it is understood that in the case in which the methodology is proposed, the province of Cádiz, there is a rich heritage generated during the Late Middle Ages that could be promoted taking into account their common history generated along more than two centuries between the border of the kingdom of Castile and the Nazaries.

The general objective of this work is to design a tourist route, using a methodology that justifies the choice of the route and the municipalities included. To achieve this goal, they are proposed as secondary objectives:

‒Study of the state of the art, referring to tourist routes and itineraries as well as to geographic information systems.

‒Quantitative and qualitative study of heritage assets under study.

‒Application of a tourism potential methodology, which takes into account tourism and culinary resources, allowing its mapping in a GIS.

With all this we hope to obtain results that in an analytical way facilitate the creation of tourist routes after a study of the possibilities offered by the region and heritage.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1. Application of gis in tourist studies

Geographic information systems are a tool that in recent years have become popular given the enormous possibilities they offer (García, 2015). They originate for military purposes in the USA after the Second World War, applying to other fields since 1962, when GIS have been used in the management of a natural resources inventory in Canada (Saudy, 2006).

From this moment on, the functions of GIS have been multiplied, using, among others, archeology (Grau Mira, 2006), land management (Nogués, 2008), cadastres (Santos Preciado, J., Azcárate Luxan, M., Cocero Matesanz, D., Muguruza Cañas, C., and García Lázaro, F., 2012) and tourism (García, 2015), since it facilitates management and decision-making (Vaz, 2015).

When defining the concept of GIS, we must bear in mind that it is a broad concept, which many authors (Burrough, 1986; Clarke; 1997; Longley et al., 2005 etc.) have explained based on their specific studies. A very widespread definition of these information systems is the one proposed by San Pedro, Serón, & Cristian (2009) according to which „it is an organized integration of hardware and software, geographic and personal data, designed to capture, store, manipulate, analyze and deploy geographically referenced information in all its forms in order to solve complex planning and management problems. It can also be defined as a model of a part of reality referred to a system of terrestrial coordinates and built to meet specific information needs „. Therefore, we can say that a GIS is a system of input, management, manipulation and output of data based on both hardware and hardware, which through the generation of various thematic layers facilitate complex analysis.

The need to use a GIS in tourism studies, lies in the importance of identifying tourist attractions and the generation of databases (Mason, 2015). These data are localized and coordinated through georeferencing (Burrough, 2015) and, therefore, indicators are obtained that allow measuring the tourist potential of a region (Letham, 2001).

The tourist potentiality is understood as the analysis of a series of variables that in an interrelated way, show the capacity of development of a tourist activity in a determined geographical space. That is why, following the thesis of Zimmer and Grassman (1996), the potential involves a prior analysis, offering a diagnosis and proposing the strategies to be developed. It is considered that a study of potentiality should make reference to the main resources and attractions as well as the structures, accessibility and resources (Ritchie and Crouch ,2005).

The desires to know the touristic potential of a geographical area goes back to the expansion of tourism in the 1960s. Thus we can highlight the studies of Miezkowski (1967), Warzynska (1974), The Organization of American States (1978), Leno (1978), LEADER II (2004), SECTUR (2005) or Cerezo and Galacho (2011) among others.

These authors have developed their own methodology, taking into account the variables required for their studies. That is why many techniques have been applied such as multivariate statistics, multicriteria evaluation, multiple response model, pairwise technique and GIS, which allow storing and modifying information so that you have a global vision of the tourism space (Ossa & Estrada, 2012).

The resulting tourism potential through the SIG, consists of two phases. The first of these is the inventory of goods and resources. This category includes all those goods that are the object of the tourism activity (heritage elements, natural heritage, etc.), but also the resources that make this economic sector possible (means of communication, hotels, restaurants, shopping centers etc), (López, 2008). For its part, the second phase consists of the cartographic representation. Tourism and territory are a constant binomial, with GIS being a tool that facilitates the promotion and definition of strategies. The availability of cartography extends not only to studies, but also allows the preparation of material for tourists (maps, videos, etc.), (Saudy, 2016).

With all this, the studies of potentiality value both tourism-consolidated areas and those more depressed, since they allow the design of alternative routes or activate tourism resources (Arteaga, 2005).

The relationship of GIS with tourism has been evident in Spain with the project „territory and tourism“ with the creation of SIGTUR whose main purpose is to promote the road to Santiago and Caravaca de la Cruz (Cebrián, 2012). Therefore, SIGTUR is created with „the purpose of dealing with statistical information regarding tourism in a special way in real time; conduct thematic cartography on tourism; develop territorial indicators to determine potential tourist areas; define / typify the tourist municipalities and establish / enhance the existing tourist areas in the Spanish territory „ (SIGTUR, 2013) . This initiative has become one of the most efficient tools given its capacity to identify the needs of the tourism market and the allocation of resources for this purpose (Ramírez and López, 2012).

Following the same objective of promotion and organization of tourist destinations, we find similar examples in Nigeria, for the enhancement of natural resources in Cross River (Ayeni, 2006) and SIGTUR applied in this case, in the state of Zulic (Venezuela). In addition, GIS have been used to determine the capacity of reception of visitors by indigenous communities as in the case of the island of Rhodes in Greece (Kyrıakou, Kapsımalıs and Sourianos, 2017).

In this way we can affirm that the use of a GIS for tourism studies is necessary to optimize the resources and patrimonial goods, create new products and inventories of goods. In this way, it facilitates the local development of more depressed tourism areas and, therefore, can offer alternatives to alleviate the regional imbalances that the tourist activity generates (Gutiérrez, 2018).

2.2. Concept and origins of tourist-cultural routes

Cultural tourism has become one of the most developed tourism modalities, given the possibilities it offers to promote a regional and sustainable development (Toselli, 2019). Culture and tourism are two elements that go hand in hand as can be seen in the Grand Tour that English young people did when they finished their studies, the great trips and expeditions of the 19th century, or the proposals of Thomas Cook (Zuelow, 2015).

The generalization of tourist routes takes place from the 1960s, when with declarations such as the Venice Charter of 1965, the UNESCO Convention in 1972 and the work of ICOMOS, culture is enhanced as a generating element of wealth and purpose of the tourism sector (Navalón, 2014).

Approaching the concept of a tourist route is not easy since there is an extensive bibliography (Parrado del Olmo, 2003; López, 2006; Moreré, 2009; Hernández, 2011; Navalón, 2014) that analyzes its characteristics and from the decade of the 1990s, its similarities and differences with the cultural tourist itineraries, after the recognition of the latter by international institutions such as ICOMOS or the Council of Europe. Some studies based on a purely philological conception (Parrado del Olmo, 2003) in which the terms of route and itinerary appear as synonyms, suggest that both realities are identical. The main argument for this lies in the fact that both routes and itineraries are developed along a route.

This hypothesis has been ruled out by the configuration of the routes and itineraries. The origin of a tourist route lies in the creation of a tourism product that relates patrimonial assets. For its part, a cultural itinerary is a historical route that responds to different human needs (religious, militant cultural, etc.) in which people do not intervene in the design of the route currently (Morére, 2012).

Having said the idea previously reflected, the tourist touristic routes are resources that “invite the visitor to travel a journey in which a certain patrimonial category predominates, be they cultural manifestations, testimonies of the archaeological or historical past, artistic and industrial heritage or natural spaces “(Hernández Ramírez, 2011).

The attempts to define cultural itineraries take on strength with their institutional recognition (Camino de Santiago in 1987) and with the creation of the International Committee of Cultural Routes and the European Institute of Cultural Routes in force since 1998 (Vidargas, 2011). In this sense, an organism such as the Council of Europe in 1992, ICOMOS in 2008 and MERCOSUR in 2009, have treated the itineraries as cultural products in which the tour itself has heritage value while the Council of Europe highlights them as “ a tour that covers one or more countries or regions, and is organized around themes whose historical, artistic or social interest is revealed as European, depending on the geographical layout of the itinerary, depending on its content and its significance “ (Council of Europe, 2002).

Therefore, the routes and itineraries can be considered as two different realities, although complementary (Arcila and López, 2012). According to Hernández (2011) “cultural itineraries can not be confused with tourist-cultural routes, because the former respond to historical criteria of authenticity, continuity and cross-cultural exchanges, while the second one are tourism inventions of convenience, promoted by public or private agents, that unite more or less homogeneous patrimonial resources and linked between them”.

After this brief analysis, it can be concluded that a tourist route is an invention of a product in which in its design there are ample capacities to choose the items, the theme and the route (Martorel, 2017). In regard to cultural itineraries, the patrimoniality of the same resides in the route perpetuated over time (Table 1).

Table 1. Differences and similarities between tourist route and cultural itinerary.

|

Elements.

|

Tourist Routes.

|

Cultural itineraries.

|

|

Origin.

|

Invention of a tourist product for its commercialization (Morére, 2012).

|

Path that historically attends to social, economic, military, religious needs, etc. (López Fernández, 2006).

|

|

Purpose.

|

Cohesioning cultural elements related to a theme for tourist use. (Martorel, 2017).

|

Attend to human needs perpetrated over time. In the case of European cultural itineraries, consolidate the European identity

|

|

Patrimonial Value.

|

The route has no heritage value, what is important are the selected milestones to which the route relates in relation to an element or common elements.

|

The route has patrimonial value, as well as the elements that make it up (Boyer Schlogel, 2007). .

|

|

Tourist use.

|

Proliferation of routes powered by public and private organizations.

|

Institutional recognition of historical roads (Council of Europe ICOMOS). Not all itineraries have a tourist use.

|

|

Creation.

|

Freedom to decide on milestones, theme and route.

|

Impossibility to decide the trajectory and milestones. Its value is to enhance the sense and cultural value of the route.

|

Source: Calderón, Arcila and Sánchez, 2018.

2.3. Tourist routes of medieval theme in Spain

Medieval heritage is a resource that has become popular in recent years in the cultural tourism sector. In this sense, the studies on medieval tourist routes offered by Roldan (2015), Martínez Biedma (2016), Antón Sánchez (2017), Morales (2018) or López de Celis (2019) among others are interesting. All these works have in common the study of a specific geographical area and the subsequent development of tourist routes, without in many cases, the route and the choice of items are justified.

Regarding the existence of tourist routes and cultural itineraries whose theme is the medieval heritage of the province of Cádiz, we find some initiatives. The most notable are the proposals by the Junta de Andalucía on its official tourism website. Thus we find:

‒Gothic and Mudejar Routes (The Kingdom of Seville 4).

‒Routes of the Andalusian legacy: it is divided into two sub-routes:

•Route of the Almoravides and Almohads.

•Route of the Umayyads.

‒Route of castles and monasteries: subdivided into two routes:

•The Atlantic Cádiz.

•The border: Cádiz and Málaga.

With regard to local scale with municipal initiatives, only the municipalities of Medina Sidonia (Route of defensive elements) and Cádiz (Medieval Cádiz and the gates of land) have tourist routes that use exclusive medieval heritage.

Finally, it must be said that many of the tourist routes promoted at municipal and regional level, include medieval heritage and goods from later times, therefore, have not been taken into account in this brief study.

3. METHODOLOGY

The methodology used consists of three parts:

a.To study in detail the geographical area: for this, bibliography, databases and institutional documents have been consulted, which enable us to know the existing cultural resources of the late Middle Ages, the hotel facilities, the means of communication, the means of transport, the heritage ethnographic, etc.

b.Analyze the potential of the selected geographic space: a contrasted potential index is used, applied to cultural heritage and whose main tool is the use of a geographic information system.

c.Creation of a tourist route: through the use of a GIS, the aforementioned data and elements have been interrelated, based on the previously calculated tourist potential.

At first, a detailed study of the late medieval heritage of the province was carried out, both qualitatively and quantitatively. The study is based on the database of the Andalusian Institute of Historical Heritage (2019), which enable us to know first-hand the typology, location and level of protection of them. In this way, the results shown in Table 2 have been obtained.

Table 2. Typologies and quantity of heritage assets during the Middle Ages.

|

Typologies

|

Quantity

|

Counties in which it predominates

|

|

Castle

|

36

|

Campiña de Jerez/ La Janda/Sierra de Cádiz/ Campo de Gibraltar

|

|

Fortification

|

4

|

Campiña de Jerez/La Janda/ Sierra de Cádiz

|

|

Walls

|

19

|

Campiña de Jerez/ La Janda

|

|

Church

|

9

|

Campiña de Jerez, Bahía de Cádiz

|

|

Alcazar

|

4

|

Campiña de Jerez

|

|

Tower

|

16

|

Campiña de Jerez/Sierra de Cádiz

|

|

Burying

|

24

|

Campo de Gibraltar

|

|

Road

|

12

|

Sierra de Cádiz/ Campiña de Jerez

|

|

Agricultural building

|

9

|

Campiña de Jerez

|

|

Deserted

|

45

|

Campiña de Jerez/La Janda

|

|

Cistern

|

39

|

Campiña de Jerez

|

|

Cathedrals

|

1

|

Bahía de Cádiz

|

|

Arc

|

28

|

Bahía de Cádiz/ La Janda/ Costa Noroeste

|

|

Hermitage

|

6

|

La Janda

|

|

Saltworks

|

9

|

Bahía de Cádiz

|

|

Settlements

|

12

|

Campiña de Jerez

|

|

Farmhouse

|

39

|

Campiña de Jerez

|

|

Villages

|

11

|

Campiña de Jerez

|

|

Tanneries

|

5

|

Campiña de Jerez

|

|

Cities

|

8

|

Bahía de Cádiz/ Campiña de Jerez

|

|

Monasteries

|

1

|

La Janda/ Campo de Gibraltar

|

Source: Calderón, 2019.

Once the low-medieval assets have been accounted for and located, the tourist use of each of these assets has been contrasted. In this way, individualized researches has been carried out on the web pages of tourism promotion at local, provincial and regional levels. In the study presented here, those low-medieval goods that can be considered as tourist resources have been selected.

Once the heritage assets and tourist development elements have been studied, the tourist potentiality index of the province has been calculated, taking into account the heritage and its interrelation with the tourist infrastructure.

In the applied case, object of this work, the model proposed by Cerezo and Galacho in 2011 is used, in which a potentiality calculation methodology is created through the use of a GIS. This model facilitates the elaboration of tables in shape format to have the selected elements and their attribute table saved in vector format. Subsequently, and following the methodology of the same author, we applied the formulation of potentiality calculation proposed by Oliveras and Anton in 1997. This equation is synthesized in:

IPTi = 0.50 * Fri + 0.30 * Fai + 0.20 * Fei

Being Fri tourist resources, Fai accessibility and Fei tourist facilities of the municipalities.

The weights that have been made have had a subjective character since there is no data on the demand.

The tourist resources that in this case have been taken into account are those belonging to the late middle age, being its highest value, since as we have said one of our objectives is to know the tourist capacity that these resources offer. Accessibility (existence of bus station, taxi service and train station) and tourism resources (hotels and restaurants) have less importance, since they are more likely to be modified by human intervention. The data of these last variables, have been obtained from the Institute of Statistics of Andalusia.

Once the municipalities with the greatest potential for tourism have been obtained, we proceed to select those municipal terms that present a better result, to integrate them into a GIS that allows the design of the tourist route.

This GIS has consisted of the following phases:

1.Elaboration of the cartographic base using a layer with the delimitation of the municipalities and the national topographic map. The use of the national topographic map is justified by the availability of most of the data that are the subject of this study.

2.Georeferencing of all those heritage assets that are tourist resources using of a point shape. In this process, a table of attributes that detail some specific data of the selected items is included in each patrimonial reference. The geo-referencing of all the late medieval resources has been carried out throughout the province and not only in the municipalities with the greatest potential. It is considered that this task is necessary to know the organization chart of the existing resources that may be included in subsequent initiatives.

3.Use of a basic road layer that allows obtaining a network analysis. This layer has served as the basis for the creation of a shape of lines that has connected the different roads with the population centers, making it possible to obtain the shortest route among the selected municipalities. In this network analysis, only road distances that facilitate the use of private vehicles have been taken into account. The use of buses or train is not considered because there are no such connections between all municipalities. However, as stated previously, the existence of train or bus stations has been accounted for in the potential study, since they can be a transport alternative for users.

The use of this resource, however, requires selecting those municipalities for which the route should start, continue and reach its end. That is why it has been considered convenient to start the tourist route in the municipality of Cádiz and after selecting the destinations of the different stops, to finish it in the same city.

The reasons that lead us to this election are justified in the first place, by the consolidation of Cádiz as a tourist destination (Port of cruises), by its availability of late medieval resources and by its geographic disposition, so that this last factor allows the displacement by the Coastal nuclei to later, move towards the interior.

4.Finally, the fieldwork has been carried out with the on-site realization of the route in order to verify its viability as well as propose an estimated time and detect the main problems that users may encounter.

4. RESULTS

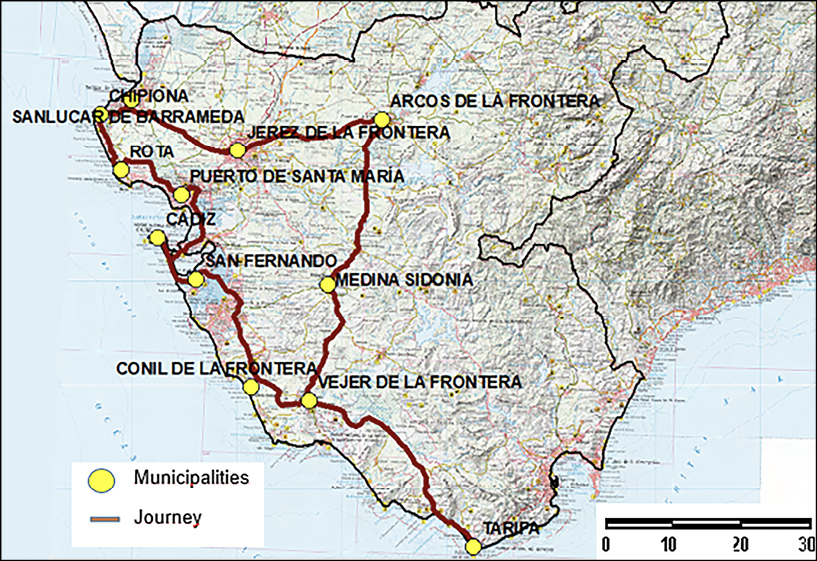

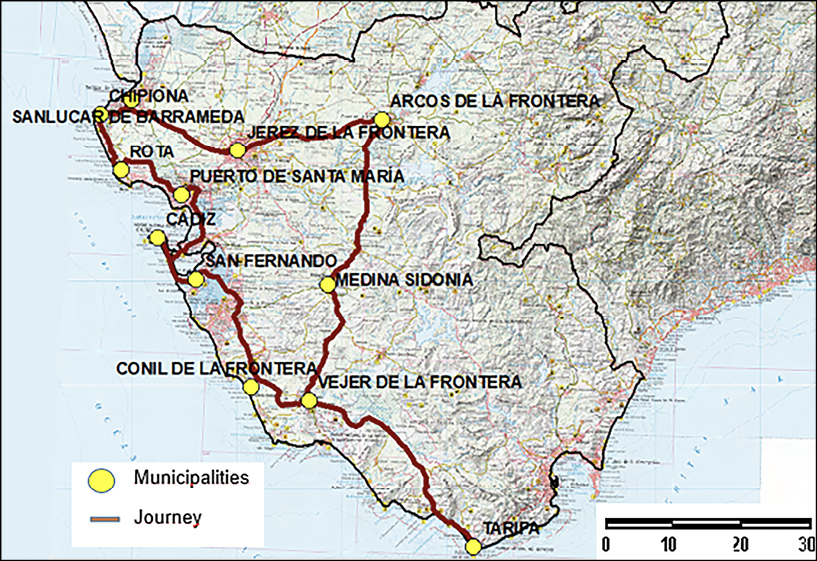

Once the methodology described above has been applied, the following maps have been obtained (map 1, map 2, map 3).

Map 1. Amount of late medieval goods with tourist use in the province of Cádiz (Spain). Source: Author‘s own research.

Map 2. Tourism potential of the late medieval heritage in the municipalities of Cádiz (Spain). Source: Author‘s own research.

Map 3. Tourist route of the low middle ages in the province of Cádiz (Spain). Source: Author’s own research.

This map shows that most of the late medieval goods are not valued from the tourist point of view, being the most used churches, castles and military structures (walls, gates, etc.).

From the analysis of the map, we conclude that the municipalities with better results are those with the best access, hotel and hotel supply, but they also have the greatest concentration of late medieval heritage. Other interior areas despite having interesting heritage resources and value, get a low score since they are located in municipalities with fewer resources and tourism, this fact affects the tourist promotion on those areas.

When interpreting the results presented in the map above, emphasis should be placed on the factors that directly affect the completion of the route. The proposed network analysis allows obtaining the shortest route between two points or population centers, including roads of all categories. The use of all types of roads is applicable in this specific case, given that in general the condition of the selected roads is good. However, it must be kept in mind that if we apply this methodology to other areas, the selection of roads should not be based exclusively on the shortest distance, but also on the performance of the same and the security they offer to users.

As stated previously, other means of transport (bicycle, bus, etc.) have not been included in the design. However, with the application of this methodology a route could be created by train or by bicycle using train tracks or rural roads in the network analysis.

At the time of carrying out the route designed in person, the fact has been taken into consideration that although the selected heritage items are tourist resources, some of them do not have a broad visiting schedule, obligating this fact to the assets that the users will know may be different depending on the time available or the day of the week the route is made. In addition, the route can be carried out partially, depending on the interests of the users.

The field work has also allowed to establish a minimum visiting time in each of the municipalities trying to contrast the previous methodology with an adequate visit time to the distance and heritage assets object of the route. In this way the proposed route itinerary has been summarized in the table 3.

Table 3. Proposed touristic route breakdown.

|

Municipalities

|

Assets

|

Overnight stays

|

|

Cádiz

|

Arco de la Rosa

Arco del Obispo

Arco de los Blancos

Catedral Vieja

|

1

|

|

San Fernando

|

Castillo de San Romualdo

|

0

|

|

Puerto de Santa María

|

Castillo de San Marcos

Iglesia Mayor

Torre Doña Blanca

|

0

|

|

Rota

|

Castillo de Luna

Muralla urbana

|

1

|

|

Sanlúcar de Barrameda

|

Palacio ducal

Castillo de Santiago

Puerta de Jerez

Puerta de Rota

Las Cobachas

Iglesia Nuestra señora de la O

|

0

|

|

Chipiona

|

Castillo de Chipiona

|

0

|

|

Jerez de la Frontera

|

Alcázar

Iglesia de San Dionisio

Iglesia de San Lucas

Muralla urbana

Iglesia de San Miguel

Iglesia de San Mateo

Iglesia Santiago

Ermita de la Ina

Iglesia San Juan de los Caballeros

|

2

|

|

Arcos de la Frontera

|

Castillo de Arcos

Palacio del conde del Águila

Muralla urbana

Iglesia Santa María de la Asunción

|

0

|

|

Medina Sidonia

|

Castillo

Arco de la Pastora

Arco de Belén

Ermita de los Santos

Villa Medieval

Torre Doña Blanca

|

1

|

|

Vejer de la Frontera

|

Torre del Mayorazgo

Murallas

Castillo de Vejer

|

1

|

|

Conil

|

Puerta de Cádiz

Puerta de la Villa

El Baluarte

Castillo

|

0

|

|

Tarifa

|

Castillo de los Guzmanes

Puerta de Jerez

|

1

|

Source: Author‘s own research.

With these results and the proposed route, a comparison should be made with the existing medieval routes in the province and which have been briefly explained in their corresponding section. The current routes encompass most of these municipalities and, consequently, the aforementioned assets. However, it is not observed in their configuration, a clear methodology that explains the reason for the choice of items, the route. In addition, only heritage assets are taken into account without deepening the provision of resources that make tourism possible. The existing medieval routes are in many cases divided by themes (castles, art architecture, etc.), so they only include goods of the same type. In the route resulting from this work, regardless of the potential of all tourism elements, goods of different types are integrated although with a similar chronology, therefore the visitor has a more complete view of the time.

5. DISCUSSION

The results obtained in this work show that the design of a cultural tourist route implies a detailed study of the heritage and tourist resources of the territory. However, there are limitations that must be taken into account when applying this methodology. The potential of municipalities may vary depending on heritage and tourism assets (closing or opening of spaces), thus, new municipalities could be included in the itinerary or exclude some. Moreover, the statistics used are not always up to date as of the route design, so it should be considered that there may be a certain margin of error in the potential calculations.

As mentioned previously, the difficult access to information and limited opening hours is one of the problems when making a tourist route. That is why the route design must have the collaboration of public bodies or property owners.

Currently many works have addressed the proposal of cultural routes of different themes. The methodology used has been diverse; creation of surveys (Sagñay Ruiz, 2019), interview with experts (Munives Laya, 2019), CO2 studies to reduce the impact of routes on the environment (Rendeiro and Martínez, 2017), agrifood studies (León Gómez & Macías Sosa , 2019) or SWOT analysis (Millán Vázquez de la Torre and Dancausa Millán, 2012) among others.

The contrast of the methodology used and which may be the subject of another study, is its application in another province of Western Andalusia or use heritage from different times so that comparisons can be made. This would allow not only the creation of routes but also, to know in what type of heritage goods municipalities and regions can specialize, being able to be a differentiating element in their tourist offer. In addition, it is considered that the results obtained could be complemented with other techniques, especially the interview with groups of experts or surveys, in this way an indicator on the viability of the route would be obtained.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Cultural tourist routes have experienced a notable proliferation in recent years, given their ability to relate heritage assets and malleability that they allow in their design, depending on the interests and objectives of designers (companies, institutions, etc.). This ability to decide the route is what differentiates the routes from the itineraries, in which the route itself has a historical-cultural value, perpetrated over time. The creation of a tourist route does not always lead to the use of a methodology in which the elaboration of these products responds to a previous study in this sense is when geographic information systems become an effective tool to generate propose tourist routes, given their capacity to put multiple variables into relation.

The territory in which the route has been applied, is a tourist region widely developed, mainly by seasonal sun and beach tourism and more recently, by nature and rural tourism. This explains that in general terms, the results that have been obtained with the tourist potential have been high, taking into account in its elaboration the low-medieval heritage resources, the tourist infrastructure or the accessibility. It must be said that tourism potential is not a static concept, but dynamic, since better or worse results can be obtained depending on the improvement or worsening of the selected variables.

Due to the possibilities they offer, potential studies have been widely developed in the cited literature and in this study, it has been possible to select those municipalities in which the development of a tourist route of these characteristics has greater possibilities. It has also allowed to identify those municipalities that need to improve their tourism infrastructure, to facilitate the enhancement of their heritage.

The design of the route has been based on the previous study and the use of GIS, although the field work is necessary to know first-hand the feasibility of the theoretical study as well as the concretion of its duration and the problems that can generate to the users.

In recent years, there are many publications that offer and design cultural tourist routes of different types (Sariego López, 2016, Ruíz Romero de la Cruz, 2017; Noriega, 2018 etc.), however, and following the idea set out in the section of results, the contribution of this work resides in the meticulous study of the tourist resources of the municipalities (hotel, hospitality accessibility) and the medieval heritage. That is why the resulting route is novel because it is justified the choice of municipalities, the layout of the route as well as the inclusion of low-medieval goods of different types (churches, wall castles etc.) that offer the user a complete view of the period historical.

With all this it has been tried to offer a new interpretation of the patrimony, sustained in the analysis of the territory that helps to its value and conservation, as well as to improve the economic development of the province.

REFERENCES

Arteaga, I. (2005). From periphery to consolidated city: Strategies for the transformation of marginal urban zones. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 1(9), 98-111.

Arcila, M., López, J. A. y Fernández Enríquez, A. (2015). Rutas turístico-culturales e itinerarios culturales como productos turísticos: reflexiones sobre una metodología para su diseño y evaluación. XXIV Congreso de la Asociación de geógrafos españoles. Universidad de Zaragoza.

Ayeni, O. (2006). A Multimedia GIS database for the Planning, Management and Promotion of Sustainable Tourism Industry in Nigeria, GIS Application to Planning Issues Shaping the Changes. XXXIII FIG Congress, Munich, Germany.

Andalusian Institute of Historical Heritage (2019): Guía digital del Patrimonio cultural de Andalucía. https://guiadigital.iaph.es/inicio

Antón Sánchez, R. y Ramón Fernández, F. (2017). Protección y puesta en valor del conjunto histórico-artístico de la Villa medieval de Moya. Gran Tour, 15, 98-118.

Burrough, P.A. (1986). Principles of Geographic Information Systems for Land Resource Assessment. Monographs on Soil and Resources Survey, 12, Oxford Science Publications, New York.

Burrough, P.A., McDonnell, R.A. & Lloyd, C.D. (2015). Principles of geographical information systems. Oxford University Press.

Calderón, D.M, Arcila M. y López, J.A. (2018). Tourist-Cultural Routes and Itineraries in the Official Tourism Portals of the Spanish Autonomous Communities. Revista de Estudios Andaluces, 35, 101-122. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/rea.2018.i35.05

Calderón Puerta, D.M. (2019). Heritage’s potentiality from low medieval in the Cádiz province (Spain) as a tourist resource. Periférica: Revista para el análisis de la cultura y el territorio. 20, 286-299.

Cebrián, A. (2012). El patrimonio, recurso turístico en el sureste de España. Editorial Académica Española, Saarbrücken, Berlín, Germany.

Cerezo Medina, A. y Galacho Jiménez, F (2011). A GIS‐based proposal for evaluating the potential of the territory for ecotourism and adventure tourism activities: an application to Sierra de Las Nieves (Málaga, Spain). Investigaciones Turísticas, 1, 134-147. doi: https://doi.org/10.14198/INTURI2011.1.09

Clarke, K.C. (1997). Conparative analysis of polygon to raster interpolation methods. Photogrammetric Engineering and remote sensing, 51 (5), 575-582.

Council of Europe. (2002). Program of the cultural itineraries of the Council of Europe. Luxembourg.

García, J. (2015). Analysis of territorial impact of third tourist boom in Canary Islands (Spain) through the application of a Geographic Information System (GIS). Cuadernos de Turismo, 36, 469-472.

Giovana Niño, S. y Danna J.N. (2016). Los sistema de información geográfica (SIS) como herramienta de desarrollo y planificación territorial en las regiones periféricas. Cidades, Comunidades e Territórios, 32 (1) 18-39. doi: https://doi.org/10.15847/citiescommunitiesterritories.jun2016.032.art02

Grau Mira, I. (2006). La aplicación de los SIG en la arqueología del paisaje. University of Alicante.

Gutiérrez Valdivieso, A., Uribe Castillo, L. y Ramírez, F. (2018). Modelando el turismo alternativo con SIG. Una propuesta para el desarrollo sostenible local con visión global. UD y la Geomática (13).

Hernández Ramírez, J. (2012). The roads of the heritage. Tourist routes and cultural itineraries. Pasos, 9 (2), 225-236.

ICOMOS. (2008). Letter of Cultural Itineraries. 16th AG. Québec (Canada), October 4.

Kyrıakou K., Hatırıs G. & Sourıanos, E. (2017). The application of GIS in Tourism Carrying Capacity Assessment for the Island of Rhodes, Greece. 15th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology Rhodes, Greece, 31 August to 2 September 2017.

León Gómez, A. D. y Macías Sosa, K. M. (2019). Análisis de la oferta gastronómica tradicional de los cantones Salitre y Samborondón, para el diseño de una ruta turística. Universidad de Guayaquil.

Longley, P., Goodchild, M. & Maguire, D. & Rhind, D. (2005). Geographic Information Systems and Science. Wiley.

López, J., Larios, C. y Campillo, L. (2008). Aplicación de un SIG para ubicar e identificar las zonas de interés turístico y la infraestructura en la reserva ecológica cascadas de reforma, Balancán, Tabasco. Semana de Divulgación y Video Científico, 173-178.

López de Celis, M. (2019). Puentes medievales: rutas con historia. Clío, Revista de Historia, 215, 82-89.

Letham, L. (2001). GPS fácil Uso del sistema de posicionamiento global. Paidotribo.

Mason, P. (2015). Tourism impacts, planning and management. Routledge. doi: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315781068

Martorell Carreño, A. (2017). Criterios de comparación entre itinerarios culturales (patrimoniales) y rutas diseñadas. Turismo y patrimonio, [S.l.], 8, 103-114, ago. 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.24265/turpatrim.2014.n8.08

Martínez Viedma, P. (2016). Ruta por los castillos de la provincia de Sevilla: Audioguía. (Trabajo Fin de Grado Inédita). Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla.

MERCOSUR (2009). Preliminary draft of Mercosur cultural itineraries. San Salvador Bay. Brazil.

Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G. y Dancausa Millán, M.G. (2012). El desarrollo turístico de zonas rurales en España a partir de la creación de rutas del vino: Un análisis DAFO. Teoría y práxis,12. doi: https://doi.org/10.22403/UQROOMX/TYP12/03

Morère Molinero, N. (2012). Sobre itinerarios culturales del ICOMOS y las rutas temáticas turístico-culturales. Una reflexión sobre su integración en turismo. Revista de Análisis Turístico, 13 (1º semestre 2012), 57-68.

Morales, J.M., Hernández, R.D. y Dancausa, G. (2018). Turismo de Castillos y fortalezas: La ruta de los templarios en España. International Journal of Scientific Management and Tourism, 4, 469-484.

Munives Laya, L.C. (2019). Propuesta de rutas turísticas para el segmento estudiantes en el distrito de Barranco. Universidad de Lima (Perú).

Navalón García, R., Rubio, L. y Ponce, G. (2014). Escenarios, imaginarios y gestión del patrimonio. Ed. Serv. Public Univ Autónoma Metropolitana -Xochimilco (Mexico) y Universidad de Alicante (España).

Nieto Masot, A. y Cárdenas Alonso, G. (2018). Sistemas de Información Geográfica y Teledetención: Aplicaciones en el Análisis Territorial. Gobierno de Extremadura.

Nogués Linares, S., Salas Olmedo, H. y Canga Villegas, M. (2008). Aplicación de los SIG a la gestión del patrimonio público de suelo. GeoFocus (Informes y comentarios), 8, 43-65.

Noriega Armijos, V., Correa-Quezada, R. y Maldonado-Erazo, C. (2018). Propuesta piloto para ruta turística patrimonial dentro de la hacienda de Casanga, Cantón paltas- Ecuador.

International Journal of Professional Business Review 3 (1), 55-65. doi: https://doi.org/10.26668/businessreview/2018.v3i1.76

Oliveras, J. y Anton, S. (1997). Turismo y planificación del territorio en la España de fin de siglo. University Rovira i Virgili.

Ossa, J. y Estrada, G. (2012). The geographic information systems and land use plans in Colombia. Perspectiva Geográfica, 1 (16), 247-266.

Pack, S.D. (2006). Tourism and dictatorship. Europe´s Peaceful Invasion of Franco´s Spain, Palgrave Macmilllan. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230601161

Ramírez Urtado, J.A. & López Bonilla, J.M. (2012). Classification of spanish tourism zones according to the structural characteristics of the offer and demand. Estudios y perspectivas en turismo, 21 (1), 34-51.

Rendeiro, R. y Martínez, P. (2017). La movilidad turística en la isla de Lanzarote: El diseño de una ruta para un autobús turístico. International Journal of Scientific Management and Tourism, 3 (3), 459- 478.

Ritchie, B. & Crouch, G. I. (2003). The competitive destination: a sustainable tourism perspective. CABI Publishing, Wallingford. doi: https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851996646.0000

Roldán Corrales, A. (2015). Rutas turísticas culturales de la provincia de Cádiz: Castillos y fortalezas medievales. Universidad de Cádiz.

Ruiz, E., Cruz, E.R. y Zamarreño, G. (2017). Rutas enológicas y desarrollo local. Presente y futuro en la provincia de Málaga. International Journal of Scientific Management and Tourism, 3 (1), 283-310.

Sagñay Ruíz, M.J. (2019). Diseño de una ruta turística enfocada al viaje en solitario en el Centro Histórico de Quito. Universidad Israel.

Salinas Chávez, E. & Medina Pérez, N. (2009). Tourism products, pillars of marketing: Two examples of the historic center of Havana, Cuba, Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo, 18 (2), 227-242.

Sariego López, I. y García del Cerro, L. (2016). La ruta turística de Carlos V los primeros pasos en la creación del producto. International journal of scientific management and tourism, 2, 439-466.

Saudy, G. (2016). Los Sistemas de Información Geográfica (SIG) en turismo como herramienta de desarrollo y planificación territorial en las regiones periféricas. Cidades, Comunidades e Territórios, 32 (Jun/2016), 18–39.

San Pedro, M.A., Serón, N. y Montenegro, C. (2009). Sistema de información geográfica aplicado a turismo y patrimonio histórico y cultural. XI Workshop de Investigadores en Ciencias de la Computación, 438-441.

Santos Preciado, J., Azcárate Luxan, M., Cocero Matesanz, D., Muguruza Cañas, C. y García Lázaro, F. (2012). La cartografía catastral urbana y su utilización en un entorno SIG. Aplicación al estudio del desarrollo residencial del sur de Madrid. Nimbus, 29, 671-685.

Toselli, C. (2019). Tourism, cultural heritage and local development. Evaluation of the tourism potential of rural villages in the province of Entre Ríos, Argentina. Pasos: Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 17 (2), 343-371. doi: https://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2019.17.024

Vaz, E., Kourtit, K., Nijkamp, P. & Painho, M. (2015). Spatial analysis of sustainability of urban habitats, introduction, Habitat International, (45) 71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.06.029

Vidargas, F. y López Morales, F.J. (2011). Cultural itineraries: management plans and sustainable tourism. Conference volumen. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. México.

Zimmer, P. & Grassmann, S. (1997). Evaluate the tourist potential of a territory. European LEADER Observatory.

Zuelow, E (2015). A history of modern tourism. Red Globe Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-36966-5

APPENDIX

List of web pages consulted

Source: Author‘s own research.

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0