DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/rea.2025.i50.04

Formato de cita / Citation: Pavanini, T. (2025). Conventional and innovative financing strategies for local public transport: insights from the italian context. Revista de Estudios Andaluces,(50), 71-89. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/rea.2025.i50.04

Correspondencia autor: tiziano.pavanini@edu.unige.it (Tiziano Pavanini)

Conventional and innovative financing strategies for local public transport: insights from the italian context

Estrategias de financiación convencionales e innovadoras para el transporte público local: perspectivas desde el contexto italiano

Tiziano Pavanini

tiziano.pavanini@edu.unige.it  0000-0001-8709-3710

0000-0001-8709-3710

Faculty of Economics, University of Genoa. Via Francesco Vivaldi, 5. 16126 Genova, Italy.

|

INFO ARTÍCULO |

ABSTRACT |

|

|

Received: 20/11/2024 Revised: 05/04/2024 Accepted: 09/05/2025 KEYWORDS Public Transport Public-private partnerships Sponsorship in public transport Corporate Mobility Management Italian Public Transport Market |

The local public transport (LPT) sector has historically been dependent on public financial resources. However, the recent economic crises have resulted in a further consolidation of this trend, largely due to the implementation of austerity policies by governments worldwide. This has resulted in a notable decline in the quality and frequency of service provision. In the context of economic scarcity, which ultimately compromises the quality of transport services, the introduction of alternative sources of finance is of paramount importance. Consequently, the involvement of private actors in the LPT sector presents a valuable opportunity to enhance the efficiency and attractiveness of the service, thereby increasing its usage among citizens. To the best of our knowledge, the existing literature has never addressed this topic. This pioneering paper aims to make a contribution to the existing literature by analysing the different forms of public-private engagement in the Italian LPT market, examining the ongoing initiatives and presenting a groundbreaking case study. To achieve this, a threefold methodology was employed. Firstly, the international literature on private sponsorship contracts in sectors other than transport was analysed. Secondly, the main search engines were used to examine the official websites and financial statements of the public transport companies. Thirdly, an interview was conducted with the communications manager of the Italian national transport association (ASSTRA). The findings of this investigation indicate that the only solutions thus far adopted are the renaming of stations and stops, the decoration of vehicles, and Corporate Mobility Management (CMM). The conclusions were alternative forms of financing for public transport are urgently needed if the service is to be efficient and appreciated by users. Furthermore, three solutions emerged that demonstrate the potential of public-private integration in the public transport sector. |

|

|

PALABRAS CLAVE |

RESUMEN |

|

|

Transporte público Asociaciones público-privadas Patrocinio en el transporte público Gestión de la movilidad empresarial Mercado del transporte público italiano |

El sector del transporte público local (TPL) ha dependido históricamente de los recursos financieros públicos. Sin embargo, las recientes crisis económicas han provocado una mayor consolidación de esta tendencia, en gran parte debido a la aplicación de políticas de austeridad por parte de los gobiernos de todo el mundo. Esto se ha traducido en un notable descenso de la calidad y la frecuencia de la prestación de servicios. En un contexto de escasez económica que, en última instancia, compromete la calidad de los servicios de transporte, la introducción de fuentes alternativas de financiación reviste una importancia capital. Por consiguiente, la participación de agentes privados en el sector del transporte público de cercanías representa una valiosa oportunidad para aumentar la eficacia y el atractivo del servicio, incrementando así su utilización entre los ciudadanos. Hasta donde sabemos, la literatura existente nunca ha abordado este tema. Este artículo pionero pretende contribuir a la literatura existente analizando las diferentes formas de compromiso público-privado en el mercado italiano de los servicios públicos de transporte de cercanías, examinando las iniciativas en curso y presentando un estudio de caso innovador. Para ello, se ha empleado una triple metodología. En primer lugar, se analizó la bibliografía internacional sobre contratos de patrocinio privado en sectores distintos del transporte. En segundo lugar, se utilizaron los principales motores de búsqueda para examinar las páginas web oficiales y los estados financieros de las empresas de transporte público. En tercer lugar, se realizó una entrevista con el responsable de comunicación de la asociación nacional italiana de transporte. Las conclusiones del trabajo fueron se requiere con urgencia formas alternativas de financiación para el transporte público si se pretende que el servicio sea eficiente y apreciado por los usuarios. Por otra parte, surgieron tres soluciones que demuestran el potencial de la integración público-privada en el sector del transporte público. |

1. INTRODUCTION

Local public transport (LPT) has always been a public finance intensive sector. Due to the recent financial and pandemic crisis, governments adopted even stricter public spending austerity policies (Ortiz & Cummins, 2021) which also affected public transport (Kar et al., 2022; Citroni et al., 2019) resulting in a reduction in the quality and frequency of service. In light of this, innovative methods of raising funds are strongly needed (Davison et al., 2014).

This is particularly pertinent given that, in addition to the primary objective of securing funding to enhance the efficacy and efficiency of the transport service, public transport authorities (PTAs) have recently augmented this imperative with a further requirement to ensure the environmental sustainability of their fleets (through the introduction of new and/or hybrid-electric vehicles), resulting in a concomitant escalation in public expenditure.

The identification of new resources is crucial for the implementation of measures designed to enhance the efficiency and appeal of the LPT. This is with a view to optimising the utilisation of available resources and encouraging greater utilisation of them. In this context, public-private partnerships can be activated to finance public transport projects, with the involvement of private companies that invest in order to obtain both an economic and a corporate image return.

The academic literature in the transport sector has paid very little attention to forms of LPT financing alternative to government subsidies. However, for the purposes of this research, the studies conducted by Jansson (1980) and Jara-Dıaz and Gschwender (2008) are relevant: the basic assumption is that PTAs, having to submit to a financial constraint imposed by their limited budget, carry out an incorrect planning of the transport service, leading to an oversizing of the offer and an insufficient frequency of the service. This article, which draws inspiration from the aforementioned studies and wants to fill this gap in literature, aims to make an original contribution to the research on this topic by analysing the Italian context. It provides insights into alternative financing methods for LPT, such as selling rights to rename bus stops and lines and Corporate Mobility Management (CMM), and presents a pioneering case study of private financing of two public transport lines, which are open to all citizens.

For this study, the top 10 PTAs in terms of turnover in Italy (2018) were examined: the pins indicate the cities where the PTAs are experimenting with selling rights practices (Milan and Genoa), CMM (Bologna), and all the other case studies examined, both at urban and regional level.

In order to identify the public-private partnership solutions adopted in the Italian market, a threefold methodology was employed. This comprised an analysis of the international literature on private sponsorship contracts in sectors other than transport, a web search on leading search engines, an examination of PTAs’ official websites and financial statements, and an interview with the communications manager of ASSTRA, the national transport association. The aforementioned steps have enabled the identification of the solutions currently operational in Italy in the field of LPT, as well as the delineation of their characteristics and replicability.

Figure 1. Top 10 Italian PTAs examined. Source: own elaboration.

This article consists of five sections. “Introduction” aims to outline the research context and purpose of this study. The “Background research” section presents an analysis of studies conducted on private sponsorships in contexts other than transport (“Literature review”) and in the transportation sector (Section 2.1). In the third section, the methodology employed by the authors in this study has been delineated. In “Results and discussion” the various solutions of public-private cooperation in the Italian transportation industry are reported. Furthermore, the case study of TPER in Bologna is presented. Finally, the concluding section, presents the final remarks, limitations and future agenda.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1. Literature review

Since there is no literature on private sponsorship methods of public transport services, it is crucial to understand the dynamics and mechanisms that govern agreements of this type in other sectors where this trend has already developed in order to evaluate a possible transfer of these skills to LPT services.

One of the first attempts in the literature to define the concept of sponsorship was that of Waite (1979), as reported in his PhD Thesis:

…the essential defining characteristics of sponsorship are that a commercial organisation provides material assistance to a recreational activity in order to gain some cost-effective commercial advantage.

Abratt et al. (1987) define sponsorship as an agreement where a subject (the sponsor) helps a beneficiary (an association, a sports team or an individual) to enable it to achieve specific results, on which the benefits for the sponsoring company in terms of visibility are based.

For Farrelly and Quester (2005) a sponsorship agreement is a strategic alliance in which two or more brands are clearly connected to the same product. Cornwell et al. (2019), studying the evolution of corporate marketing strategies over time, report how traditional mass-media marketing has been replaced by more effective advertising methods, defined as “indirect”, such as sponsorship agreements, product placement and use of influencers on social media. Among these innovative branding strategies, sponsorship represents one of the most effective and profitable solutions for companies (Alonso-Dos Santos et al., 2016).

The actors involved, i.e. sponsor (sponsoring entity) and sponsee (sponsored entity), enter into collaboration agreements through the instrument of the sponsorship contract, defined by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) in the “International Code on Sponsorship” as:

Any commercial agreement by which a sponsor, for the mutual benefit of the sponsor and a sponsored party, contractually provides financing or other support in order to establish an association between the sponsor’s image, brands or products and a sponsorship property in return for the rights to promote this association and/or for the granting of certain agreed direct or indirect benefits.

The economic reasons why sponsor companies decide to access the sponsorship tool concern the promotion of their brand through greater visibility, increased profits because of a better perception of the product by customers, direct access to a targeted audience and increased customer loyalty.

It becomes crucial for sponsoring companies to estimate correctly the economic impacts of their sponsorship. Meenaghan (1991) describes five evaluating strategies for the effectiveness of a sponsorship agreement such as media exposure (the economic value of the sponsorship by comparing the media exposure time or space obtained with the equivalent cost if it had been purchased as an advertisement), sponsorship awareness of customers, number of sales, users’ feedback and cost-benefit analysis (CBA). However, some of these evaluation techniques revealed critical as customers’ awareness and the number of sales directly attributable to the sponsorship agreement are difficult to calculate (Copeland et al., 1996).

Maestas (2009) reports that ROI (Return on Investment) (figure 2), although it is one of the most used indicators by sponsors (Nickell & Johnston, 2020), is not able by itself to explain all the impacts of a sponsorship agreement but must be supported by other measures such as ROO (Return on Objectives), media exposure and market value analysis.

Figure 2. Methods of evaluating the value of sponsorship agreements.

Source: own elaboration based on Meenaghan (1991) and Maestas (2009).

ROI considers the relationship between the value generated by the sponsorship and the cost of the investment made. The value generated can be measured through the achievement of specific marketing objectives such as increasing sales, improving brand awareness or increasing customer loyalty.

The ROO, which includes several evaluation techniques described by Meenaghan (1991), focuses on the impact and effectiveness of the project in achieving its objectives, assessing how much value and benefits have been obtained compared to the investments made. These objectives can be of different nature and can concern for example the increase of brand awareness, the acquisition of new customers, the increase of sales or the retention of existing customers. ROO is particularly used in marketing and advertising strategies to evaluate ROI beyond the financial aspects, focusing on the performance of the entire project against its set objectives.

Furthermore, the market value analysis, considering various factors to determine the value of a sponsorship, including the size and profile of the audience involved, the media coverage and engagement generated by the sponsored event or activity and the effect on brand positioning, aims to evaluate the benefits that the sponsor can obtain through the sponsorship, such as exposure of the brand, visibility, access to a specific target audience, association with positive values or images, etc.

Two other relevant aspects are the duration of the sponsorship agreements and the simultaneous participation of several sponsors (“sponsorship clutter”). As regards the duration, sponsorships can be temporary (e.g. short-term events) or permanent (e.g. financing the construction of public works such as stadiums, museums, theatres, etc.). If the first type of contract provides for faster bureaucratic procedures, long-term or permanent sponsorships have a greater impact on consumer brand awareness with a consequent sales increase (Walraven et al., 2014; Walraven et al., 2016). As far as sponsorship clutter is concerned, the literature reports that the simultaneous presence of several competing sponsors can have negative effects on the brand image transfer to consumers and thus on the effectiveness of sponsorship (Cornwell et al., 2000; Carrillat et al., 2010; Walraven et al., 2016). Nevertheless, Boeuf et al. (2018) state that the clutter effects on users mainly depend on the perceived congruence between sponsor and sponsee.

Most of the sponsorship contracts globally concern sporting, musical and cultural events, as they are able to increase quickly the value of the brand (Candelo, 2014). This tool is still not widespread in transportation: the aim of this research is to explore the possibility of adapting marketing principles from other areas to this sector.

In this respect, the findings of Gwinner and Swanson (2003) in their study on the impact of fan identification on the returns of sponsorship contracts are relevant. The authors conclude their analysis of the sports sector, carried out using structural equation modelling, by stating that the more fans perceive a strong sense of involvement and identification with their team, the better the returns on sponsorship. The study looked at four different types of outcomes (i.e. sponsor awareness, attitudes towards the sponsor, patronage of the sponsor and satisfaction with the sponsor) and all showed rather high values corresponding to fans who were involved and strongly identified with their team.

The findings of Gwinner and Swanson (2003) provide insights for the case study of this article. The local authority needs to act to strengthen users’ sense of identity with their area and community: this will also improve the results of the sponsorship, with obvious benefits for both the sponsoring companies and the PTA. For instance, a primary step in this process is the establishment of a robust and consistent visual identity, one that is capable of conveying local values and fostering a sense of civic pride. It is imperative for PTAs to organise cultural or social events and initiatives that actively engage the community and position public transport as a pivotal element of collective life.

The customisation of services based on the characteristics of the neighbourhoods – through decorations, artistic content or cultural references – has the potential to increase user identification. Furthermore, the use of digital technologies and gamification strategies has the capacity to stimulate interaction (e.g. badges or apps that track user involvement and allow them to “level up” in the transport community), favouring a more participatory and dynamic relationship. Loyalty programs that offer benefits thanks to the support of local sponsors also contribute to creating a virtuous circle between users, the territory and companies.

Furthermore, the integration of influencers or citizens as transport ambassadors has the potential to reinforce the sense of community and promoting education on sustainable mobility in schools and among young people helps to create a lasting and positive bond with the service. This symbiotic relationship has the potential to yield a mutually beneficial outcome, leading to an enhancement in the perceived value of sponsorship, a phenomenon that is advantageous for all parties involved, including sponsors, communities, and local authorities.

From the analysis of the academic literature carried out in this section, it emerged that the utilisation of sponsorship in disparate sectors, such as sport, culture and education, proffers pertinent insights for the domain of public transport. The transferable methods include the transfer of naming rights for stations or lines, the utilisation of advertising spaces on vehicles and infrastructure, the sponsorship of services or street furniture, temporary thematic campaigns, initiatives related to corporate social responsibility and co-branding or loyalty programmes. When adapted to the context of local transport, these practices can represent valid and innovative financing strategies.

2.2. Sponsorship in the transportation sector

The sponsorships present in the transport sector are today mainly limited to the business of purchasing the right to rename specific bus lines, train lines, train and metro stops and stations (Scauzillo, 2016).

Selling naming rights for transportation infrastructure has grown widespread in several nations in the last two decades (Rose-Redwood et al., 2019). Furthermore, as has been the case in the Canadian city of Winnipeg, since 2009, the municipality has decided to sell also the naming rights of bridges, overpasses and parking lots (Rose-Redwood et al., 2021).

Transportation authorities can raise more money to pay for infrastructure construction, maintenance, and operating expenses by letting individuals or companies purchase the naming rights (Vuolteenaho, 2022). This can be beneficial for both the PTAs and the companies involved. As Vuolteenaho (2022) states, for the public entity selling naming rights can provide a significant source of revenue, which can be used to fund infrastructure improvements, station upgrades, and maintenance works, particularly in situations where public funding might be limited. Furthermore, by generating additional revenue, PTAs can potentially reduce the burden on fare payers, leading to more affordable and accessible transportation options.

The sponsors, renaming high-traffic areas such as key urban transport infrastructures, can significantly enhance brand visibility and recognition, helping to create a positive association in the minds of commuters and the public. Naming rights allow for exposure to a diverse audience, enhancing brand reach and potential customer engagement. Nevertheless, sponsors supporting public transit through naming rights can improve their reputation, demonstrating a commitment to the community and its transportation needs. It is evident that the optimal means of attaining such objectives is through the sponsorship of prominent, high-traffic lines or infrastructure, particularly in densely populated urban centres.

Rose-Redwood et al. (2019) report that selling naming rights allows local governments to increase municipal revenues without raising taxes, but at the same time, this practice erodes the democratic value and cultural identity of urban public spaces. The commodification of urban toponymy therefore runs the risk of threatening the public memory of various public spaces (Boyd, 2000), and this provokes opposition from citizens. Indeed, there are several cases of British football fans resisting the renaming of their stadiums: Newcastle and Southampton, to name a few (Light & Young, 2015).

The present study sets out to analyse the Italian case study in order to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of public-private integrations in the public transport sector. The extant literature, as previously referenced, exclusively focuses on the purchase by private companies of the right to rename bus/train lines or stations. In this research, in addition to describing the cases of selling rights in the Italian context, it is intended to take a further step and investigate one of the first examples at global level of creation of a public transport line by a private company for the use of all citizens.

3. METHODOLOGY

The methodology employed in this research was developed through a multifaceted and integrated approach, designed to provide an in-depth and detailed analysis of the funding and sponsorship strategies implemented by Italian Public Transport Authorities. The principal objective was to examine the forms of private involvement these PTAs embrace and the sponsorship models that prove most efficacious within the Italian context. The methodology, depicted in figure 3, comprised a number of discrete yet interrelated phases, each of which contributed to the provision of a comprehensive and multidimensional overview.

Figure 3. Methodology used in this work. Source: own elaboration.

One of the initial tasks was to examine the operations of the Italian public transport authorities. This phase comprised a comprehensive examination of the financial statements of the Top 10 Italian PTAs in terms of annual turnover and related market share (ranking as of 2018)[1], with the objective of analysing the funding structure and identifying any sponsorship practices. The statements provided a detailed overview of revenues generated through sponsorship and collaborative partnerships. The most recent documents available were selected, with particular attention paid to line items relating to revenue from sponsorship, commercial agreements and strategic alliances. The aim of this analysis was to identify not only the monetary value of these sponsorships, but also their structural characteristics. The review of these documents identified patterns in the types of companies involved in sponsorship, the structure of the partnerships and the specific objectives of these collaborations.

Concurrently, an exhaustive examination of the official websites of the aforementioned authorities was undertaken. This activity enabled the collection of publicly available information, which proved invaluable in elucidating the funding policies and partnership initiatives with private entities. This analysis was further supplemented by a web search conducted using reference search engines. The online research was carried out to gather data on the financial allocations and sponsorship strategies of public transport authorities in Italy. The main search engines - Google, Bing, Yahoo and Firefox - were used to search for relevant information. The research phase involved formulating a number of specific keywords and keyword combinations, including terms such as “public transport authority funding”, “public transport sponsorship”, “budget transport entities” and “regional transport funding”. This keyword strategy enabled targeted searches to locate data related to the funding mechanisms and sponsorship models used by Italian public transport authorities.

Each search result was reviewed and only those deemed relevant were further analysed to determine their accuracy and relevance. Priority was given to official sources such as government websites, public transport authority publications and reputable industry reports. Academic publications were also consulted to provide a theoretical basis for the data collected.

A further fundamental component of the work was the analysis of international literature (Section 2). This phase comprised a systematic review of academic studies, reports and case studies from international contexts, with the objective of acquiring a more comprehensive understanding of the financing and sponsorship strategies employed in the public transport sector on a global scale. This enabled the identification of models, trends and good practices that could also be pertinent to the Italian context.

Furthermore, an interview was conducted with ASSTRA (Associazione Trasporti), the Italian public transport association representing 140 PTAs and authorities, which collectively account for 75% of the market. The association represents a strategic reference point for the public transport sector, helping to support companies in their role as providers of essential services for collective mobility. Through its actions, ASSTRA aims to promote dialogue between the public and private sectors and to encourage innovative solutions to the challenges of modern mobility.

The interview offered a well-informed and up-to-date insight into the dynamics of private involvement and emerging trends in financing local public transport in Italy (the structure of the interview is in the appendix 1 at the end of the article).

Conducted via Microsoft Teams, the interview was designed to cover key topics including financial strategies, sponsorship campaigns and communication initiatives undertaken by ASSTRA’s member organisations. The decision to engage directly with ASSTRA was strategic, as it provided access to up-to-date insights and first-hand information on sponsorship practices in different regions and organisations. This interaction also allowed the researchers to contextualise the data obtained from financial documents and online research within the actual decision-making processes and trends observed in the industry.

Following the collection of data from all the sources - search engines, official websites, financial documents, and the ASSTRA interview - the information about the Italian context was systematically reviewed, verified and triangulated. Data from public financial documents were cross-referenced with findings from the interview to identify common patterns and potential discrepancies.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The analysis of the financial statements of the Top 10 Italian PTAs in terms of annual turnover and related market share led to the results illustrated in table 1.

Table 1. Examination of the financial statements of the Top 10 Italian PTAs (data as of 2023).

|

PTA |

Renaming |

Decoration of vehicles |

CMM |

Total revenue (€) |

Sponsorship revenue[2] (€) |

% Sponsorship revenue/Total Revenue |

|

ATM |

✓ |

✓ |

937.697.270 |

16.701.000 |

1,78% |

|

|

ATAC |

✓ |

970.575.203 |

11.302.047 |

1,16% |

||

|

GTT |

✓ |

423.326.000 |

2.231.000 |

0,53% |

||

|

COTRAL |

✓ |

347.560.366 |

558.000 |

0,16% |

||

|

AVM VENEZIA |

✓ |

299.793.305 |

5.893.790 |

1,97% |

||

|

ENTE AUTONOMO VOLTURNO |

✓ |

313.843.006 |

NOT SPECIFIED |

/ |

||

|

TPER |

✓ |

✓ |

294.026.000 |

1.031.000 |

0,35% |

|

|

ACTV |

✓ |

249.926.202 |

NOT SPECIFIED |

/ |

||

|

ANM |

✓ |

194.678.377 |

1.385.000 |

0,71% |

||

|

AMT |

✓ |

✓ |

246.848.520 |

772.656 |

0,31% |

Source: own elaboration.

As illustrated in table 1, merely two PTAs currently employ selling rights practices for bus and metro stations and lines (ATM and AMT). All PTAs rent advertising spaces inside and outside their vehicles. Conversely, only one PTA experiments with CMM (TPER), the subject of this paper. Table 1 also reports total revenues, revenues from sponsorships and advertising, and the percentage incidence of the latter on the total.

In order to better contextualise the area of operation of the PTAs selected for this survey, table 2 provides some basic statistical information on the territories to which the PTAs belong.

Among the common patterns, the involvement of private sponsors for the direct financing of services or infrastructure, such as the naming of stations or lines, stands out (2 PTAs today plus 1 in the past). The sale of advertising space is a common practice, with advertisements on vehicles, stations and infrastructure. In addition, in the Italian scenario, only one agreement has so far been identified with private companies to guarantee the mobility of their employees, with the aim of financing dedicated lines or concessionary agreements (see section 4.1). This initiative has been applied in a densely populated urban centre, where there is greater visibility for the sponsors.

Despite the lack of initiatives, some differences can also be highlighted. The main differences concern the approach between regions and cities: large urban centres, such as Milan and Rome, are more likely to experiment with innovative sponsorship than rural areas. The type of infrastructure involved varies, with branding of railway stations implying long-term agreements, while buses and trams are used for short-term campaigns. Another distinguishing element is social acceptance: some communities are more open to branding (e.g. residents of large cities such as Milan and Genoa), while others show resistance linked to cultural sensitivities or the protection of public heritage. Finally, the duration and nature of the agreements vary, as do the types of sponsors involved, ranging from multinationals to local companies.

Table 2. Public Transport Authorities and basic statistics of their Cities/Regions.

|

PTA |

City/Region |

Population (2024) |

Area (km²) |

Population Density (inhabitants/km²) |

Predominant Economic Activities |

|

ATM |

Milan |

1,371,499 |

181.8 |

7,539 |

Finance, Fashion, Industry, Technology |

|

ATAC |

Rome |

2,751,747 |

1,287.4 |

2,138 |

Tourism, Government, Services |

|

GTT |

Turin |

851,199 |

130.2 |

6,538 |

Automotive, Manufacturing, Technology |

|

COTRAL |

Lazio Region |

5,714,745 |

17,236.5 |

332 |

Agriculture, Tourism, Manufacturing |

|

AVM / ACTV |

Venice |

250,290 |

414.6 |

603 |

Tourism, Shipbuilding, Manufacturing |

|

Ente Autonomo Volturno |

Campania Region |

5,593,906 |

13,667.9 |

409 |

Agriculture, Tourism, Manufacturing |

|

TPER |

Bologna |

390,098 |

140.9 |

2,768 |

Food Industry, Education, Services |

|

ANM |

Naples |

913,704 |

119.0 |

7,678 |

Tourism, Shipbuilding, Agriculture |

|

AMT |

Genoa |

562,422 |

240.3 |

2,340 |

Shipping, Trade, Tourism |

Source: own elaboration.

As a result of the aforementioned work, it was possible to outline the state of the art of the Italian context. In Italy, as in other countries, the public transport sector requires large amounts of public funding, and its costs have recently increased as a result of political decisions requiring public transport operators to switch to electric vehicles and to make a wide range of technological adjustments (Aamodt et al., 2021). Because of this, local governments employ commercial sponsorship to raise extra funds from the private sector (Vuolteenaho, 2022). In the public transportation industry, there are primarily two ways to achieve this goal: sale of the name rights of bus or metro lines and stations (Scauzillo, 2016; Rose-Redwood et al., 2021), and full or partial decoration of vehicles with advertising panels (Hess & Bitterman, 2016). Figure 4 also shows the third option discussed in this study, namely the corporate mobility management: it will be described in the next section.

Figure 4. Sponsorship modalities employed and hypothesized in Italian LPT sector.

Source: own elaboration.

With regard to the partial or total decoration of vehicles, already widely spread even at a global level (Hess & Bitterman, 2016), it is applied in all 20 Italian regional capitals.

Regarding the sale of station and line naming rights, activity already widespread in other global metropolises such as Dubai (Sotoudehnia, 2013), the first Italian city to introduce such a measure was Rome in 2013, with an agreement signed between ATAC (Rome PTA) and Vodafone to rename the metro station “Termini – Vodafone”. Recently, however, only the northern cities of Milan and Genoa have included this practice (relating only to the renaming of stations) in their revenue generation strategies, and only Genoa continues to this day.

The Milan administration began in 2015 to allow private companies to put their name on the main metro stops through a sponsorship contract: Mediaset Premium was the forerunner in the San Siro Stadio stop. The sponsorships have so far concerned only a few stops on the M5 line, the last metro line built through project financing.

However, in 2020 the City of Milan decided to change strategy and prevent the renaming of stations by selling the exclusive right to name the whole line: the official reasons are not known, but the local authorities probably want to protect the cultural identity of the station names (Boyd, 2000), which are more characteristic than the name of the line.

As a result, while private companies no longer have the right to brand the name of the stations, they can still obtain exclusive rights to the internal advertising space, creating an immersive user experience.

Currently, the only two stations where this type of branding is active are the San Siro Stadio station (Coca Cola) and the Tre Torri station (Allianz Generali).

In addition, many of the other stations on the M5 line have been subject to a partial branding exercise for a period of less than a year. Figure 5 shows the configuration of the M5 line in Milan in 2019, with the stations subject to renaming activity (red) and the only station (green) subject to the temporary sale of internal advertising space (but not “renaming”).

Figure 5. Renamed metro station (red) and the station with immersive user experience (green), Milan, in 2019. Source: own elaboration.

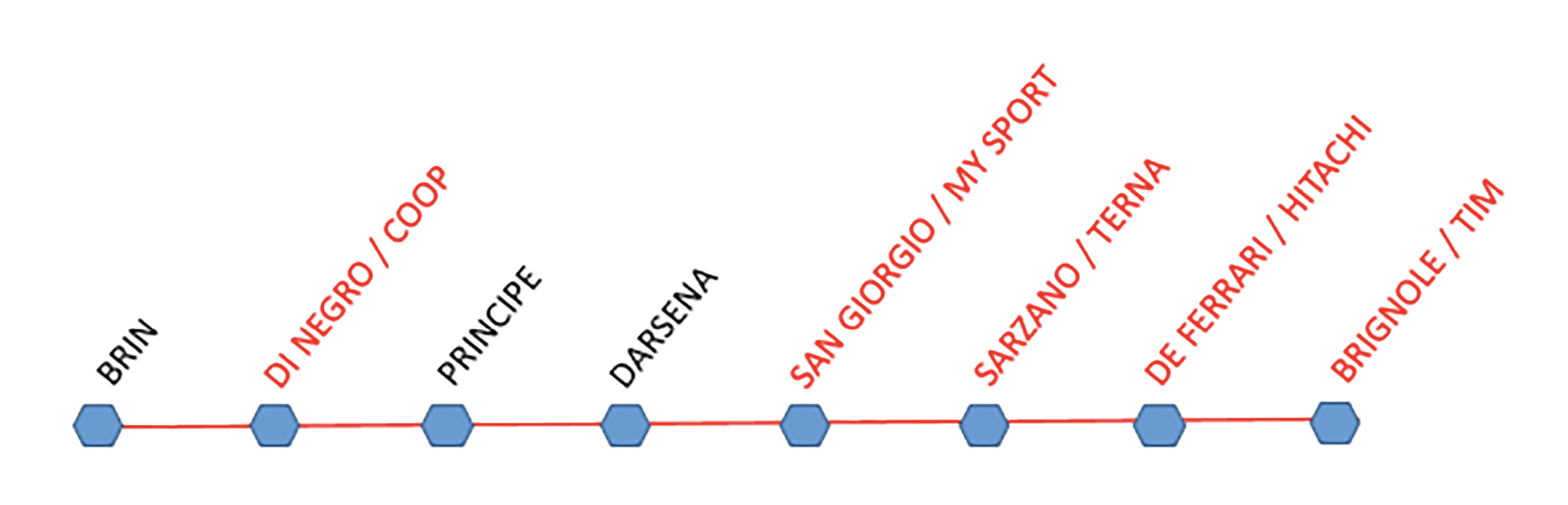

In the city of Genoa, the “Your Metro” project was launched in February 2020, aimed at attracting sponsors and new revenue through the renaming of some metro stops. To date, five out of eight stops have been sponsored by private companies who have added their brand to the original name of the station (Figure 6). The “Adopt a Bus” project, on the other hand, aims to raise funds by selling advertising space (€25,000 per year each) to sponsors both inside and outside the vehicles. Partial or full decoration of vehicles also applies to metro trains.

Figure 6. Renamed metro stations (red) in Genoa, Italy, in 2023. Source: own elaboration.

AMT’s sponsorship and advertising revenues for 2023 increased to €772,656, as presented in table 1, constituting 0.31% of the total value of production of the PTA. When compared with the company’s revenues from sales and services (core business), which equalled €80,191,517 in 2023 and accounted for 32.49% of the total, it is clear that there is still much room for improvement on this path.

Genoa’s PTA, AMT Spa, wants to take things a step further by securing private funding for a whole service line.

In June 2023, AMT announced a public tender for the award of a 24-month sponsorship contract (€950,000 in total). This contract concerns the single line 782, which connects Santa Margherita Ligure with the village of Portofino, one of the most glamorous and exclusive locations in the world, capable of attracting millions of tourists. AMT is offering the winning sponsor high visibility by fully decorating all eight electric buses operating on the line and renaming the line with its own brand.

In relation to the third aspect of figure 4, Corporate Mobility Management (CMM) is a strategic approach adopted by companies with the objective of managing and optimising the travel of their employees, customers and suppliers (Wong, 2018). This is done with the intention of reducing the use of private cars, improving environmental sustainability and increasing the overall efficiency of travel related to work (Gorges et al., 2021; Klopfer et al., 2023; Frank et al., 2024). The corporate mobility manager is the professional figure responsible for developing, implementing and monitoring sustainable mobility strategies within a company. He is responsible for implementing mobility solutions, promoting and encouraging the use of alternative transport modes, creating partnerships with car sharing and bike sharing services, and improving accessibility to public transport services. Examples of this kind of initiatives include carpooling programs with internal platforms for sharing cars between employees traveling on similar routes, incentives for cycling with the provision of safe parking, showers and changing rooms, and economic incentives for bikers. The promotion of teleworking and time flexibility reduces the number of trips at peak times, although the literature shows that the overall number of trips with LPT increases (Ravalet & Rérat, 2019), while agreements with public transport companies offer discounted or free passes to employees.

One such example is the practice of numerous Italian PTAs entering into commercial agreements with universities to permit students enrolled to travel on their respective networks at no cost (main case studies in table 3).

Table 3. Main case studies of agreements between Italian Universities and local PTAs.

|

University |

PTA |

Agreement |

|

University of Brescia |

Arriva Italia |

50% discount on public transport passes for students |

|

University of Florence |

Autolinee Toscane |

Discounts of up to 82% on the cost of local public transport passes for students |

|

Università di Padua |

Trenitalia Busitalia |

Welfare PLUS 10% offer, a 10% discount valid for the purchase of tickets for private travel on Frecciarossa, Frecciargento and Frecciabianca trains. Discounts on local buses. |

|

University of Siena |

Autolinee Toscane |

Discounts on local LPT. |

|

University of Trento |

Trentino Trasporti Spa |

“Libera circolazione” allows students to travel on public transport at a discounted rate throughout the Province of Trento. |

|

University of Turin |

GTT GRANDA BUS |

Refund of GTT and GRANDA BUS transport service subscriptions purchased. |

Source: own elaboration.

Furthermore, it is necessary to describe the case study of the first agreement in Italy between a private company and the local PTA for the construction of two new public transport lines. This specific project was financed entirely by Philip Morris Manufacturing & Technology Bologna with the intention of providing a benefit not only to the employees of the company but also to the wider community of the city of Bologna.

The tobacco manufacturing company decided to fully finance the creation of lines 676 and 677 which connect the city of Bologna with the Valsamoggia industrial area located in the hinterland. This is the first agreement of this kind in Italy for multimodal transport (TPER and Trenitalia are naturally involved in the initiative). Furthermore, in order to encourage its employees to reduce car use, Philip Morris also provided them with a free subscription to use on board all TPER vehicles in the metropolitan area. Figure 7 shows the new multimodal line 677, which connects Bologna’s main railway station to the Philip Morris factory.

Figure 7. New line 677 in Bologna from Bologna Central Station and Philip Morris.

Source: own elaboration based on TPER.it (2024).

The agreement between TPER and Philip Morris is a virtuous example of public-private cooperation in public transport. The Bologna PTA has also concluded more than 40 CMM agreements with companies in the area, aimed at promoting the use of public transport at reduced costs (around 30,000 season tickets). In this type of agreement, TPER undertakes to offer a fare reduction of up to 15% of the value of the annual subscription in return for a contribution from the other party of between 5 and 15%. Another good example of a CMM established by TPER over the years is the one signed with the company that manages Bologna Airport (Aeroporto di Bologna). In this case, TPER offers a very tailored season ticket to the airport’s employees (almost 3.000 people): they can benefit from different ticket versions according to their needs, choosing between train, bus, shuttle and car-sharing (table 4). Figure 8 shows some of the private companies and public entities involved in CMM with TPER.

Table 4. Aeroporto di Bologna agreement with TPER.

|

Users |

Mode of transport |

|

Aeroporto di Bologna employees (approximately 3,000) |

All TPER buses of the urban, suburban and extra-urban lines of the Bologna area |

|

Marconi Express People Mover shuttles |

|

|

Metropolitan Railway Service trains (urban area, lines to/from Casalecchio, San Lazzaro, Rastignano, Portomaggiore and Vignola) |

|

|

Regional trains |

|

|

A carnet of minutes of the free-floating electric car sharing |

Source: own elaboration based on TPER.

Figure 8. Private companies and public entities involved in mobility management. Source: TPER.it (2024).

On the basis of what has been said in this section, it is now possible to make some final observations in the next section.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The global trend of reduced public spending on urban transport is a consequence of the implementation of austerity policies by governments in order to respond to periods of economic crisis, such as the global financial collapse of 2008 and the recent global pandemic. In light of the aforementioned scenario, there is a risk that local public transport will lose ground to private transport. It is therefore evident that alternative forms of financing for public transport are required with the utmost urgency if the service is to be made efficient and appreciated by users. It is only through such measures that the desired shift in modal use from private to public transport can be achieved, with concomitant benefits in terms of the environment and public health. To the best of our knowledge, this topic has not been addressed in academic literature thus far. Consequently, this study makes a pioneering contribution to the field by exploring the potential for private sector involvement in LPT for the first time. By analysing international literature, initially focusing on private sponsorship contracts in sectors where they are already present and then in reference to the transport industry, the authors were able to present a comprehensive overview of the current state of public-private partnerships in this sector.

Furthermore, two additional methodological steps were undertaken to achieve this objective within the Italian context. Initially, the Italian PTAs were identified through a web search on leading search engines, an examination of their official websites, and an analysis of their financial statements. Finally, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the Italian LPT sector, the communications manager of ASSTRA, the national transport association, was interviewed. From this inquiry, three solutions have emerged that demonstrate the potential for public-private integration in the public transport sector. These include the renaming of metro lines and stations (currently operational in Genoa and Milan), the partial or total decoration of vehicles (already implemented in numerous locations), and Corporate Mobility Management (CMM).

In examining the case study of TPER in Bologna, we delved deeply into the subject of CMM, which is the strategic approach adopted by private companies with the aim of managing and optimising the travel of their employees, customers and suppliers. The principal objective of this type of initiative is the establishment of a service that is accessible not only to employees of the sponsoring company but also to the general public, including employees.

This initiative represents the inaugural tangible example of efficacious involvement of private actors in the public transport sector. This was made possible through the financing by Philip Morris Manufacturing & Technology Bologna of two public transport lines that connect the city of Bologna with the industrial area where the company’s manufacturing facility is situated. The service, which was required for the transportation of company employees, is now accessible to all citizens, thereby increasing the reach and efficiency of the TPER service. The TPER case study serves as a model for private financing of public transport, offering clear benefits for both companies and the community.

For private companies, the primary benefit is the potential to enhance the mobility of employees, customers and suppliers, thereby optimising logistical efficiency and reducing travel expenditures. Moreover, these initiatives contribute to enhancing the company’s reputation by underscoring its commitment to sustainability and social responsibility, while also fortifying its connection with the local community.

From a community standpoint, these agreements signify an enhancement of the public transport provision, through the financing of new lines or services that, although initially designed for company employees, are made accessible to all citizens. This enhancement in accessibility, alongside the concomitant reduction in private traffic and the resultant decrease in environmental impact, underscores the multifaceted benefits of these initiatives. The integration of public and private sectors fosters the efficiency of urban mobility systems, yielding tangible benefits in terms of inclusivity, sustainability, and the quality of service for the entire community.

CMM practices are also critical in supporting local economic development by improving access to key employment centres and infrastructure, such as industrial estates or airports. For example, the partnership between TPER and Philip Morris in Bologna facilitates employees’ commutes while improving connectivity to the airport area, making the region more attractive for business and investment.

The objective of this study is to present the current state of public-private partnerships in the Italian market, with a view to offering guidance to PTA managers and policy makers on how they might enhance the efficiency of their public transport services. It should be noted that this study was conducted exclusively at the Italian level, thereby leaving the possibility for future research in other countries. Moreover, further research could encompass the utilisation of questionnaires and in-depth interviews with PTA management and policy makers.

Responsibilities and conflicts of interest

The author undertakes to disclose any existing or potential conflict of interest in relation to the publication of his article.

REFERENCES

Aamodt, A., Cory, K., & Coney, K. (2021). Electrifying transit: A guidebook for implementing battery electric buses (No. NREL/TP-7A40-76932). National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), Golden, CO (United States). https://doi.org/10.2172/1779056

Abratt, R., Clayton, B.C., & Pitt, L.F. (1987). Corporate objectives in sports sponsorship. International journal of Advertising, 6(4), 299-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.1987.11107030

Alonso-Dos-Santos, M., Vveinhardt, J., Calabuig-Moreno, F., & Montoro-Ríos, F. (2016). Involvement and image transfer in sports sponsorship. Engineering Economics, 27(1), 78-89.

AMT (2023). How to take your brand to Portofino. https://www.amt.genova.it/amt/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Presentazione-portofino-ITA.pdf

Beard, J.R., de Carvalho, I.A., Sumi, Y., Officer, A., & Thiyagarajan, J.A. (2017). Healthy ageing: moving forward. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 95(11), 730. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.203745

Boeuf, B., Carrillat, F.A., & d’Astous, A. (2018). Interference effects in competitive sponsorship clutter. Psychology & Marketing, 35(12), 968-979. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21149

Boyd, J. (2000). Selling home: Corporate stadium names and the destruction of commemoration. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880009365580

Burlando, C., & Cusano, I. (2018). Growing Old and Keep Mobile in Italy. Active Ageing and the Importance of Urban Mobility Planning Strategies. TeMA-Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, 43-52.

Candelo, E. (2014). Nuove opportunità per il marketing. Strategie di marca e sponsorizzazioni di eventi sportivi, culturali, sociali e musicali. GRAPHICUS, 5-6.

Caprio, V. (2008). Progetto Reti degli Sportelli per lo Sviluppo. I contratti di sponsorizzazione. http://focus.formez.it/sites/all/files/dossier_sponsorizzazioni.pdf

Carrillat, F.A., Harris, E.G., & Lafferty, B.A. (2010). Fortuitous brand image transfer: Investigating the side effect of concurrent sponsorships. Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367390208

Citroni, G., Lippi, A., & Profeti, S. (2019). In the shadow of Austerity: Italian local public services and the politics of budget cuts. In Lippi, A., Tsekos, T. (Eds.) Local Public Services in Times of Austerity across Mediterranean Europe. Governance and Public Management (pp. 115-140). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76225-8_6

Copeland, R., Frisby, W., & McCarville, R. (1996). Understanding the sport sponsorship process from a corporate perspective. Journal of Sport management, 10(1), 32-48. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.10.1.32

Cornwell, T.B., Relyea, G.E., Irwin, R.I., & Maignan, I. (2000). Understanding long-term effects of sports sponsorship: Role of experience, involvement, enthusiasm and clutter. International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 2(2), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-02-02-2000-B005

Cornwell, T.B., & Kwon, Y. (2020). Sponsorship-linked marketing: Research surpluses and shortages. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48, 607-629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00654-w

Currie, G., & Fournier, N. (2020). Why most DRT/Micro-Transits fail–What the survivors tell us about progress. Research in Transportation Economics, 83, 100895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2020.100895

Davison, L., Enoch, M., Ryley, T., Quddus, M., & Wang, C. (2014). A survey of demand responsive transport in Great Britain. Transport Policy, 31, 47-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2013.11.004

Enoch, M., Potter, S., Parkhurst, G., & Smith, M. (2006). Why do demand responsive transport systems fail?

Fatima, K., & Moridpour, S. (2019). Measuring public transport accessibility for elderly. In MATEC Web of Conferences (Vol. 259, p. 03006). EDP Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201925903006

Frank, L., Klopfer, A., & Walther, G. (2024). Designing corporate mobility as a service–Decision support and perspectives. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 182, 104011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2024.104011

Furuhata, M., Daniel, K., Koenig, S., Ordonez, F., Dessouky, M., Brunet, M. E., & Wang, X. (2014). Online cost-sharing mechanism design for demand-responsive transport systems. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 16(2), 692-707. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2014.2336212

Gorges, T., & Holz-Rau, C. (2021). Transition of mobility in companies–A semi-systematic literature review and bibliographic analysis on corporate mobility and its management. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 11, 100462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2021.100462

Gwinner, K., & Swanson, S. R. (2003). A model of fan identification: Antecedents and sponsorship outcomes. Journal of services marketing, 17(3), 275-294. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040310474828

Hess, D.B., & Bitterman, A. (2016). Branding and selling public transit in North America: An analysis of recent messages and methods. Research in transportation business & management, 18, 49-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2016.01.001

Jansson, J.O. (1980). A simple bus line model for optimisation of service frequency and bus size. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 53-80.

Jara-Díaz, S.R., & Gschwender, A. (2009). The effect of financial constraints on the optimal design of public transport services. Transportation, 36, 65-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-008-9182-8

Kar, A., Carrel, A. L., Miller, H.J., & Le, H.T. (2022). Public transit cuts during COVID-19 compound social vulnerability in 22 US cities. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 110, 103435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2022.103435

Klopfer, A., Frank, L., & Walther, G. (2023). Quantifying emission and cost reduction potentials of Corporate Mobility as a Service. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 125, 103985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2023.103985

Lan, J., Xue, Y., Fang, D., & Zheng, Q. (2022). Optimal Strategies for Elderly Public Transport Service Based on Impact-Asymmetry Analysis: A Case Study of Harbin. Sustainability, 14(3), 1320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031320

Laws, R., Enoch, M., Ison, S., & Potter, S. (2009). Demand responsive transport: a review of schemes in England and Wales. Journal of Public Transportation, 12(1), 19-37. https://doi.org/10.5038/2375-0901.12.1.2

Light, D., & Young, C. (2015). Toponymy as commodity: Exploring the economic dimensions of urban place names. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(3), 435-450. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12153

Maestas, A.J. (2009). Guide to sponsorship return on investment. Journal of Sponsorship, 3(1).

Mageean, J., & Nelson, J.D. (2003). The evaluation of demand responsive transport services in Europe. Journal of Transport Geography, 11(4), 255-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6923(03)00026-7

Meenaghan, J.A. (1983), “Commercial sponsorship”. European Journal of Marketing, 17(17), 5-73. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004825

Meenaghan. T, (1991). Sponsorship—Legitimizing the medium. European Journal of Advertising, 25(11). 5-10. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000000627

Nickell, D., & Johnston, W.J. (2020). An attitudinal approach to determining Sponsorship ROI. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 38(1), 61-74. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-11-2018-0512

Ortiz, I., & Cummins, M. (2021). Global austerity alert: looming budget cuts in 2021-25 and alternative pathways. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3856299

Perera, S., Ho, C., & Hensher, D. (2020). Resurgence of demand responsive transit services–Insights from BRIDJ trials in inner west of Sydney, Australia. Research in Transportation Economics, 83, 100904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2020.100904

Ravalet, E., & Rérat, P. (2019). Teleworking: Decreasing mobility or increasing tolerance of commuting distances? Built Environment, 45(4), 582-602. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.45.4.582

Rose-Redwood, R., Vuolteenaho, J., Young, C., & Light, D. (2019). Naming rights, place branding, and the tumultuous cultural landscapes of neoliberal urbanism. Urban Geography, 40(6), 747-761. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1621125

Rose-Redwood, R., Sotoudehnia, M., & Tretter, E. (2021). “Turn your brand into a destination”: Toponymic commodification and the branding of place in Dubai and Winnipeg. In Naming Rights, Place Branding, and the Cultural Landscapes of Neoliberal Urbanism (pp. 100-123). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003163268-6

Scauzillo, Steve. (2016, December 7). LA County Metro seeing $$$$ with new opportunity to sell naming rights to rail lines, stations. San Gabriel Valley Tribune. https://www.sgvtribune.com/2016/12/07/la-county-metro-seeing-with-new-opportunity-to-sell-namingrights-to-rail-lines-stations

Sun, G., & Lau, C.Y. (2021). Go-along with older people to public transport in high-density cities: Understanding the concerns and walking barriers through their lens. Journal of Transport & Health, 21, 101072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2021.101072

TPER (2024, June 11). https://www.tper.it/bo-677

Van Hoof, J., Marston, H.R., Kazak, J.K., & Buffel, T. (2021). Ten questions concerning age-friendly cities and communities and the built environment. Building and Environment, 199, 107922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107922

Vuolteenaho, J. (2022). Toponymic Commodification: Thematic Brandscapes, Spatial Naming Rights and the Property–Name Nexus. The Politics of Place Naming: Naming the World, 109. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394188307.ch6

Waite, N. (1979). Sponsorship in context.

Walraven, M., Bijmolt, T.H.A., & Koning, R.H. (2014). Dynamic effects of sponsorship: The development of sponsorship awareness over time. Journal of Advertising, 43(2), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.835754

Walraven, M., Bijmolt, T., Koning, R., & Los, B. (2016). Benchmarking Sports Sponsorship Performance: Efficiency Assessment With Data Envelopment Analysis. Journal of Sport Management, 30(4), 411-426. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2015-0117.

Wong, Y.Z. (2018). Corporate Mobility Review; How Business can Shape Mobility.

Wong, R.C.P., Szeto, W.Y., Yang, L., Li, Y.C., & Wong, S.C. (2018). Public transport policy measures for improving elderly mobility. Transport policy, 63, 73-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.12.015

World Bank (2023). Urban Development. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview.

World Health Organization (2020a). Ageing.

World Health Organization. (2020b). Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report.

APPENDIX 1

STRUCTURE OF THE INTERVIEW WITH ASSTRA

Introduction and General Context

- What is the current state of sponsorship agreements between public transport companies and private entities in Italy?

- Is it possible to brand public transport services under Italian regulations?

Sponsorship Models and Practical Applications

- Are sponsorship agreements more commonly focused on selling advertising spaces by PTAs to private entities, or on mobility agreements for employees of private companies?

- When a transport service is financed by a private entity, is it open to all citizens, or is it exclusively reserved for the employees of the funding organization?

- Are PTAs able to manage advertising spaces independently, or must they outsource this management to third parties?

Application Dynamics and Urban Contexts

- In which urban contexts or types of infrastructure are these sponsorship agreements more easily applied and more widely adopted?

- What are the dynamics that govern sponsorship agreements related to station naming or the branding of public transport infrastructure?

Challenges and Critical Issues

- What are the main challenges or critical issues that limit the spread of sponsorship agreements between PTAs and private entities?

- Are such agreements generally well accepted by the population? What are the possible consequences of these deals on the social fabric of the area?

Comparison with Other Sectors and Success Stories

- Are the dynamics governing commercial agreements in public transport similar to those found in other sectors, such as the sports industry?

- What are the best examples of successful private sponsorships in public transport at the national level? Can these successful cases be replicated in other cities or contexts?

Future Perspectives and Stakeholders

- Who are the most suitable and strategic stakeholders for the implementation of such sponsorship agreements?

- Do you believe these tools have growth potential and can contribute to making public transport systems more sustainable?