DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/rea.2024.i47.09

Formato de cita / Citation: Zakhia, S., & Pérez-Pérez, B. (2024). Does the colonial past influence the model of tourism development? The case of Ehden (Lebanon). Revista de Estudios Andaluces,(47), 186-213. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/rea.2024.i47.09

Correspondencia autores: belenperez@ugr.es (Belén Pérez-Pérez)

Sally Zakhia

Sally.zakhia@net.usj.edu.lb  0000-0001-5705-645X

0000-0001-5705-645X

Department of Geography. Faculty of Humanities. Saint Joseph University of Beirut.

Saint-Joseph University. Rectorate - Damascus Road. PO Box 17-5208 Mar Mikhael. Beirut, Lebanon.

Belén Pérez-Pérez

belenperez@ugr.es  0000-0002-9780-2338

0000-0002-9780-2338

Department of Human Geography. Faculty of Philosophy and Letters. University of Granada.

University Campus of Cartuja. 18071 Granada, Spain.

|

INFO ARTÍCULO |

ABSTRACT |

|

|

Received: 06-10-2023 Revised: 06-11-2023 Accepted: 22-11-2023 KEYWORDS Tourism Legacy of colonialism Sustainable tourism Tourism participation Endogenous resources Lebanon |

This research studies whether the tourism development model in Ehden (Lebanon) is sustainable and balanced, or whether, on the contrary, it responds to the unsustainable pattern of its colonial past. To this end, interviews with local stakeholders, surveys of residents and tourists were carried out and analysed using descriptive statistics and cross-sectional data techniques. The results show that local stakeholders want to promote an integrated tourism development model in Ehden based on territorial resources that involve the local population. The population is willing, for the most part, to get involved in the tourism development model of the town, and tourists are committed to diversified activities centred on the natural and cultural heritage of Ehden, which value the town’s specific resources. However, it has been detected that this is a demand of those with high income that stays in high quality hotels or rural accommodation and is concentrated in the summer months, which denotes a strong seasonality and unsustainability of tourism. It is concluded that, although the colonial past is present in the territory, there is currently a great interest from all the agents involved in tourism to promote an integrated tourism model that could help to boost economic diversification. |

|

|

PALABRAS CLAVE |

RESUMEN |

|

|

Legado turístico del colonialismo Turismo sostenible Participación turística Recursos endógenos Líbano |

La presente investigación estudia si el modelo de desarrollo turístico de Ehden (Líbano), es sostenible y equilibrado o, si por el contrario, responde al patrón de insostenibilidad de su pasado colonial. Para ello, se han realizado algunas entrevistas a agentes locales, encuestas a residentes y a turistas que han sido analizadas utilizando técnicas de estadística descriptiva y datos cruzados. Los resultados muestran que los agentes locales quieren promover un modelo de desarrollo turístico integral en Ehden basado en los recursos territoriales que involucre a la población local. La población está dispuesta, en su mayoría, a involucrarse en el modelo de desarrollo turístico de la localidad y, los turistas, apuestan por actividades diversificadas centradas en el patrimonio natural y cultural de Ehden y valoran los recursos exprofeso de la localidad. Sin embargo, se ha detectado que se trata de una demanda de alto nivel adquisitivo que se aloja en hoteles o alojamientos rurales de alta calidad y se concentra en los meses de verano, lo que denota una fuerte estacionalización e insostenibilidad del turismo. Se concluye que, si bien el pasado colonial está presente en el territorio, actualmente hay un gran interés de todos los agentes que intervienen en el turismo para promover un modelo turístico integral que podría ayudar a impulsar la diversificación económica. |

Tourism has undergone constant expansion and substantial diversification throughout the decades, making it the fastest expanding economic sector (Lee & Chang, 2008). According to UNWTO (2019), prior to the COVID19 pandemic, the tourism sector’s turnover equals or even exceeds that of exports of oil, foodstuffs and automobiles.

Moreover, tourism has emerged as a major actor in international trade, while also serving as one of the primary sources of income for many developing countries. It’s expected, based on the report of the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) (2016) that the contribution of travel and tourism to gross domestic product (GDP) will reach 10.8% by the end of 2026. Nevertheless, there is also strong competition between destinations that plan positioning strategies and marketing actions to implement a whole series of developments actions and new infrastructures, which attract the attention of a greater number of potential visitors to their territory (REF).

The direction of causality between tourism development and economic growth, however, is debatable (Aslan, 2013; Ekanayake & Long, 2012). It has been shown that the benefits of territories, highly focused on tourism, are limited in terms of economic growth and socio-economic resilience (Romão, 2021), due to the fact that they are highly vulnerable to the effects of events such as pandemics (Duro et al., 2021) or climate change (Magnan et al., 2013; Csete & Szécsi, 2015).

In light of these premises, it is critical to include tourism as an activity of endogenous local development (Hummelbrunner & Miglbauer, 1994; Dinis et al., 2019). However, many former colonies of Western countries are resistant to such a model, as imperialism has fostered sustained inequality and unjust and oppressive forms and processes of tourism (Santer, 2019; Higgins-Desbiolles, 2022). This has resulted in an inherited tourism model that has been exogenously organised and articulated to fulfil the requirements of former settlers, continuing its legacy as a neo-colonial phenomenon, which pulls power away from local and regional levels, and concentrates it in the hands of foreign-owned corporations (Williams, 2012) and/or it has provided local economic elites with new opportunities to perpetuate their historical socio-economic advantages (L´Espoir, 2011).

The origin of tourism in Lebanon stems from a time when it was a French colony (Devine & Ojeda, 2017; Higgins-Desbiolles, 2022), implying that it is responding to an external development model that could be controlled by foreign tour operators.

The aim of this work is to find out the main characteristics of Ehden tourism as well as its environmental and social sustainability. The study will be carried out through social research techniques based on preliminary interviews and surveys of residents and tourists designed on the basis of these interviews. It will analyse whether Ehden’s tourism model responds to a tourism model inherited from its colonial past or, on the contrary, whether it is a tourism model that involves the population and is based on the enhancement of local endogenous resources. This work represents an important contribution to research and knowledge of the characteristics of tourism in the mountainous areas of Lebanon, as it is the first to be carried out in this locality using social research techniques and one of the few studies on tourism in this country.

In recent decades, there has been a stream of research related to the growth of tourism and its impact on regional development. Its importance has been widely studied in both developed and developing countries (Henry & Deane, 1997). However, developing countries are becoming important players in the tourism sector and are becoming aware of its economic potential, which has led to an exponential growth of tourism. Some research shows that tourism boosts economic growth by increasing foreign exchange reserves (McKinnon, 1964), which leads to increased investment in new infrastructure, human capital and competition (Blake et al., 2006). It also leads to industrial development, creates employment and increases incomes (Lee & Chang, 2008). Therefore, inbound tourism is considered by several authors to generate positive externalities (Andriatis, 2002).

Furthermore, studies suggest that tourists seek a different and unique destination experience (Poussin, 2009) and increasingly choose to immerse themselves in the true culture of the place (Chambers, 2009). However, many rural destinations in developed countries are saturated with an “artificialisation” of tourism experiences and a loss of territorial identity and cultural trivialisation (Hubbard & Lilley, 2000; Roca & de Nazaré, 2007). Other rural destinations, on the other hand, are preserving their authenticity and can use tourism as a tool for local and/or regional development (Valeiro & Ribeiro, 2007) (figure 1).

Territorial identity refers to a feeling of belonging to a community because of the similarity between members who share cultural values, social values, and common interests attached to a certain territory (Capello, 2018). Therefore, this identity is rooted in the uniqueness of the geographical space and based on associated natural or cultural features. (Alaoui & Abba, 2019; Paasi, 2003) Contrarily, the uniqueness of a place is determined by the interactions between the population and its environment (Pollice et al., 2003). Thus, territorial identity is composed of landscape and climatic or hydrographic (Carneiro et al., 2015; Stoffelen et al., 2019), as well as cultural and social characteristics (Ou & Bevilacqua, 2017). Moreover, some of these characteristics can be considered both determinants and expressions of identity (Simon et al., 2010).

Today, rural areas are increasingly seen as tourist destinations, not only as agricultural regions (Bessière, 1998).

However, the success of tourism development in these territories is dependent on the local population’s involvement as well as the territory’s resources and value (Aguirre et al., 2018), as these serve as the foundation to create integrated products and packages with enough substance to provide real experiences (Kastenholz & Lima, 2011).

While a destination’s ability to compete depends on the abundance of tangible and intangible resources, its capacity to achieve the desired tourism development is correlated with its ability to adopt management practices. This takes into account the relationships that are built between the participants that make up the system as a +-whole (Minguzzi & Presenza, 2010).

Tourism continuously presupposes a connection between social and economic activities and the territory in which they take place, while identifying all relevant resources. The prerequisites for creating the strategies and organisational structure of a tourism system are reinforced by the process of identifying tourism resources (Grant, 1994; Teece et al., 1997). Therefore, in order to have a complete picture of all the tourism resources of a given local system, it is necessary to recognise and order the various components of the natural and built environment (mountains, churches, castles, monuments, etc.). These are in addition to the set of intangible resources, such as local culture or territorial brands and even human resources (Solima & Minguzzi, 2014). Therefore, the debate on the development of social and economic tourism activities is largely based on the examination of a territory.

Although tourism development is based on the promotion of endogenous territorial resources (Spilanis & Vayanni, 2004), we cannot ignore the fact that these resources belong to the local population. However, in former colonial countries, settlers subjugated part of the territorial resources and culture. They introduced their language, religion, gastronomy, festivals and tourism model, among other aspects. Many of these territories have acquired a strong tourist vocation, losing most of their remaining traditional activities and, with them, their identity. Furthermore, they have developed so that activities and accommodation have a strong Western European component (Winter, 2009). This was done to meet the expectations of the settlers with whom the former colonies still maintain a strong link today (McKercher & Decosta, 2007), as they continue to be the main sources of foreign tourists (Kothari, 2015).

Hence, tourism cannot be deemed sustainable or beneficial to the local economy as a whole, because increased tourism damages endogenous resources required by the local population, hurting their environmental circumstances, economic well-being, and increasing social inequity (Briasoulis, 2002). This translates into carrying out a diagnosis of tourism in the territory in order to understand its weaknesses and threats as well as its strengths and opportunities. The objective is usually to recover lost or forgotten traditional activities along with the development of new ones, taking into account the conservation of the natural and cultural environment and incorporating a tourism model that rewards justice with the local population (Jamal & Camargo, 2012; Alisa & Ridho, 2020).

Figure 1. Conceptual map. Source: own elaboration.

Lebanon, one of the smallest states in the Middle East, is at the centre of the eastern Mediterranean basin and occupies a crossroads position between the three continents of Asia, Africa and Europe (figure 3). Historically, Lebanon was a centre of trade and culture that dates back to Phoenician times. It used to be a passageway between the East and West for caravans, traders, missionaries and conquerors. Today the country offers visitors a rich natural, geological, archaeological, historical, and cultural heritage. Known as the “land of milk and honey,” Lebanon is still an exception in the Middle East, where more than 80% of the land is desert (Buccianti-Barakat, 2006). Due to its natural conditions, Lebanon benefits from important hydrographic and agricultural resources. Wine making is an 8,000 year old practice in which a significant amount of wine used to be exported to neighbouring countries such as Egypt, Greece and Assyria. The cedar forests are legendary and during the 1990’s several forests were classified as natural reserves such as the Shouf Biosphere Reserve which represents 5% of the country’s total area.

Lebanon is a territorial reservoir of plant diversity. About 2,600 recorded species make it the richest country in flora and fauna in the Middle East and one of the most important points of global biodiversity and exceptional botanical richness in the region (Sattout, 2009; Bou Dager-Kharrat & Rouhan, 2018). The western range pertaining to the Lebanese Mountains, Mount Lebanon and its villages, has been densely inhabited for a very long time. Between 1920 and 1943 Lebanon was a French colony. In fact, tourism in Lebanon dates back to the time when it was a French colony.

The research was conducted in the northern region, specifically located on Mount Lebanon. Ehden, poetically called “The Garden of Eden”, located at 1500 metres above sea level, is located in the province of Zgharta and belongs to the Ehden-Zgharta township.

Prior to the founding of Zgharta (almost 500 years ago), Ehden was the only town in the area. Nowadays, it’s a well-known summer destination famous for its dry climate, abundant water, and dense forest. However, Ehden has harsh winters, with snows covering most of the town for almost 5 months of the year (December – April).

As per Snow Forecast Lebanon, on average, Ehden has during the first week of December a maximum of 5 degrees Celsius, reaching a low of minus 8 degrees Celsius during the month of January. As for snow, Ehden sees 4 days per week of snow during winter (mostly January and February) reaching about 60 cm in height (figure 2).

Figure 2. Average Snow and Rain in Ehden. Source: Snow Forecast Lebanon.

Ehden is home to the Horsh Ehden Nature Reserve, located on the northwestern slopes of Mount Lebanon. It was classified as a Nature Reserve in March 1992, making it the most important part of its natural heritage. Although the reserve is considered relatively small - some 1,000 hectares and covering 0.1% of the country’s total area, environmental activist Ricardo Haber has, so far, recorded more than 1,058 plant species, representing almost 40% of all wild flora in Lebanon. Moreover, several specialists and researchers consider this forest to be a true relic of nature “Here we find the ecosystem most similar to an ancient forest, thirty-nine species of trees coexist, such diversity is very rare, in Europe only one or two species are found in vast areas,” points out botanist Myrna Semann Haber.

Ehden also has a rich cultural heritage, including traditional architecture and archaeological sites. The religious heritage brings together the structures (buildings), objects and ritual practices specific to each religion and region. Because of the variety of religions in the country, this harmonious coexistence attracts devotees and those interested in religious history and culture.

Figure 3. Location map of Ehden (Lebanon). Source: own elaboration with ArcGIS from World Topographic Map.

The country’s ethnographic heritage is also very varied, with the region’s gastronomy also presenting an attractive image of the country’s culture and its geographical and economic identity. During the summer, several cultural events enliven the town, including the Ehdeniyat International Festival which attracts visitors from all over the country. In addition to its varied natural, cultural and ethnographic heritage, Ehden is listed as “The Favourite Lebanese Village” (L’Orient-Le Jour, 2016) and “The most beautiful Lebanese Village” (NGO Ajmal Baldet Lebnen, 2018) (figure 4).

Figure 4. Ehden during the month of February 2022. Source: own photo taken in Ehden.

A mixed research model was utilised that included qualitative (preliminary interviews with local stakeholders) and quantitative (surveys of residents and tourists) methods. The objective was to find out whether or not Ehden’s tourism model corresponded to an inherited tourism model from its colonial past and how it was perceived by local stakeholders, the local population and tourists.

Seven preliminary interviews were conducted with local stakeholders following a semi-directed interview model (Annex I), which was to be carried out with local council officials, heritage and tourism specialists, entrepreneurs and tourist guides. The aim was to find out what tourism is like in Ehden in order to understand the general context, the main resourcesand its strengths and weaknesses. These interviews served as the basis for the design of the survey questions that were distributed to residents and tourists.

A total of 138 surveys were conducted in Ehden, 70 of which were residents and 68 were tourists, at different times from 2021-2022. Although these are small samples, there are no official records of the population of Ehden and there is a large variability among the sources consulted, although there are fewer and fewer people living permanently in the municipality (150-200 inhabitants) due to the fact that Zgharta (40,000 inhabitants) is much closer and has many more services. Even so, many efforts were made to collect enough responses to allow for respondent variability, but as this was at the time of the COVID19 pandemic, answer questionnaires and tourism was gradually recovering in the town, although it had not yet reached pre-pandemic levels.

In the surveys carried out with residents and tourists, respondents were characterised according to age, gender, level of education, place of residence and occupation. There was also another part of the survey with specific questions for each group. For the present research, only some of the questions from the resident survey and the tourist survey were selected which are part of a wider investigation.

From the residents’ survey, we selected the questions on whether they were in favour or against promoting tourism in Ehden and the questions asking them about their interest and ways of participating in promoting tourism development projects in the locality (Annex II).

From the tourist survey, questions related to the main motivations for visiting Ehden were selected in order to characterise the type of trips made to the village, the type of accommodation preferred by tourists, the length of their stay and whether or not they would like to return to Ehden (Annex III).

Some of the questions were designed as multiple-choice questions in which respondents were asked to indicate whether they agreed or disagreed with a number of issues. This data had to be adapted by subdividing these questions into several questions in which the answers were binomial in nature, counting the options chosen as 1 and those not chosen as 0.

Subsequently, a descriptive statistical analysis of the results as a whole was carried out for each of the samples (residents and tourists), followed by an analysis using contingency tables to perform cross-analyses of the respondents’ preferences according to gender, age or education. The results of the surveys were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics.

With this information, the researchers were able to learn about some of the main characteristics of Ehden’s tourism model, its limitations, and its strengths.

From consultations with representatives of the municipal corporation, experts from the heritage and tourism sector, entrepreneurs and local guides, much information was gleaned about how tourism works in Ehden. Tourism in Ehden is highly seasonal, concentrated during the summer and a few weekends during the winter. Ehden has changed from a traditional mountain town to a tourist-oriented holiday and recreational municipality, where services to the local population have been disappearing or losing continuity. This has led the population to move for most of the year to Zgharta, a nearby coastal service town. Furthermore, people leave Ehden during winter because of the weather and its harsh conditions, making accessibility difficult because of snow and low temperatures. Most houses are not equipped to handle such winters.

According to stakeholders consulted, tourists coming to Ehden mostly stay in high quality hotels and/or rural hotels and particularly value the local gastronomy. This aspect was of concern to the representatives of the local administration, who highlighted the architectural and archaeological heritage of the region and expressed that the municipality does not have archives or registered data on these monuments, which are managed externally by the Department of Antiquities (Lebanese Ministry of Culture). However, they expressed the need for a detailed study of all the monuments, houses and markets in the region with a goal to restore and enhance them in order to attract more tourists to Ehden leading to a comprehensive tourist destination. With respect to religious heritage, the Lebanese Maronite Patriarchate is responsible for the maintenance of churches, monasteries and religious monuments, and the municipality has no power to oppose its decisions. The natural heritage, represented by the Horsh Ehden Nature Reserve, is also managed independently and funded by national and international contributions. For these reasons, the municipal authorities want to promote a comprehensive tourism project for Ehden based on the creation of a territorial brand and, create new hiking trails in the Ehden region, connecting it to other regions such as the Holy Valley of Qadisha, which is a major tourist attraction, as well as revaluing cultural, natural and religious heritage.

According to table 1, which represents the sociodemographic characteristics of the local population, women and men are equally represented in the sample, with 50%-50%. However, by age, the 21-35 age group is over-represented in the sample with 50% of all respondents. This is followed by the 36-50 age group with 34% of the total. The age group with the lowest representation is the 51+ age group with 14%. Most of the respondents are in their prime working years (21-50 years), which lends credibility to this study and the opinions and perspectives of the respondents are useful for tourism stakeholders (79%).

Table 1. Summary of locals’ profile.

|

Variables |

Categories |

% |

Variables |

Categories |

% |

|

Gender |

Female |

50% |

Occupation |

Student |

7% |

|

Male |

50% |

Domestic work |

7% |

||

|

Prefer not to say |

0% |

||||

|

Age |

21-35 |

50% |

Working |

79% |

|

|

36-50 |

34% |

Unemployed |

3% |

||

|

Retired |

4% |

||||

|

>51 |

16% |

||||

|

Residence |

Ehden (Lebanon) |

82% |

Education Level |

Primary/Secondary School |

9% |

|

Out of Ehden |

18% |

Universitary Studies |

91% |

Source: percentage statistical analysis with SPSS. |

It should be noted that the majority of the inhabitants who responded to the survey have higher education, which, although this may differ to some extent from the population average (where there are probably more people without higher education), is very realistic with the formation of the age groups that are most represented. It should be noted that although the sample was distributed homogeneously throughout the territory in paper and digital format, it is a voluntary survey and it is clear that these specialised topics related to tourism planning are of more interest to the active population with a higher level of education.

In order to know the opinion of the population, they were asked if they would agree with the implementation of a comprehensive tourism development model in Ehden, in line with the local authority’s idea of improving the conservation of the natural, cultural and religious heritage and promoting tourism around all territorial resources, to which a large majority answered “Yes” (50.0%), 30% answered “Maybe” and 20% answered “No”.

When analysing the results by age group, we found that those most interested in promoting an comprehensive tourism development model in Ehde are above 51, followed by those aged between 36-50 and finally those under 35, with interest increasing with age.

There is a higher proportion of women (51.4%) interested in developing a comprehensive tourism development model in Ehden, with (48.6%) on the other hand for men.

In terms of education, those most interested in promoting an comprehensive tourism development model in Ehden are those with university studies (53.1%), followed by respondents with primary or secondary studies (16.7%).

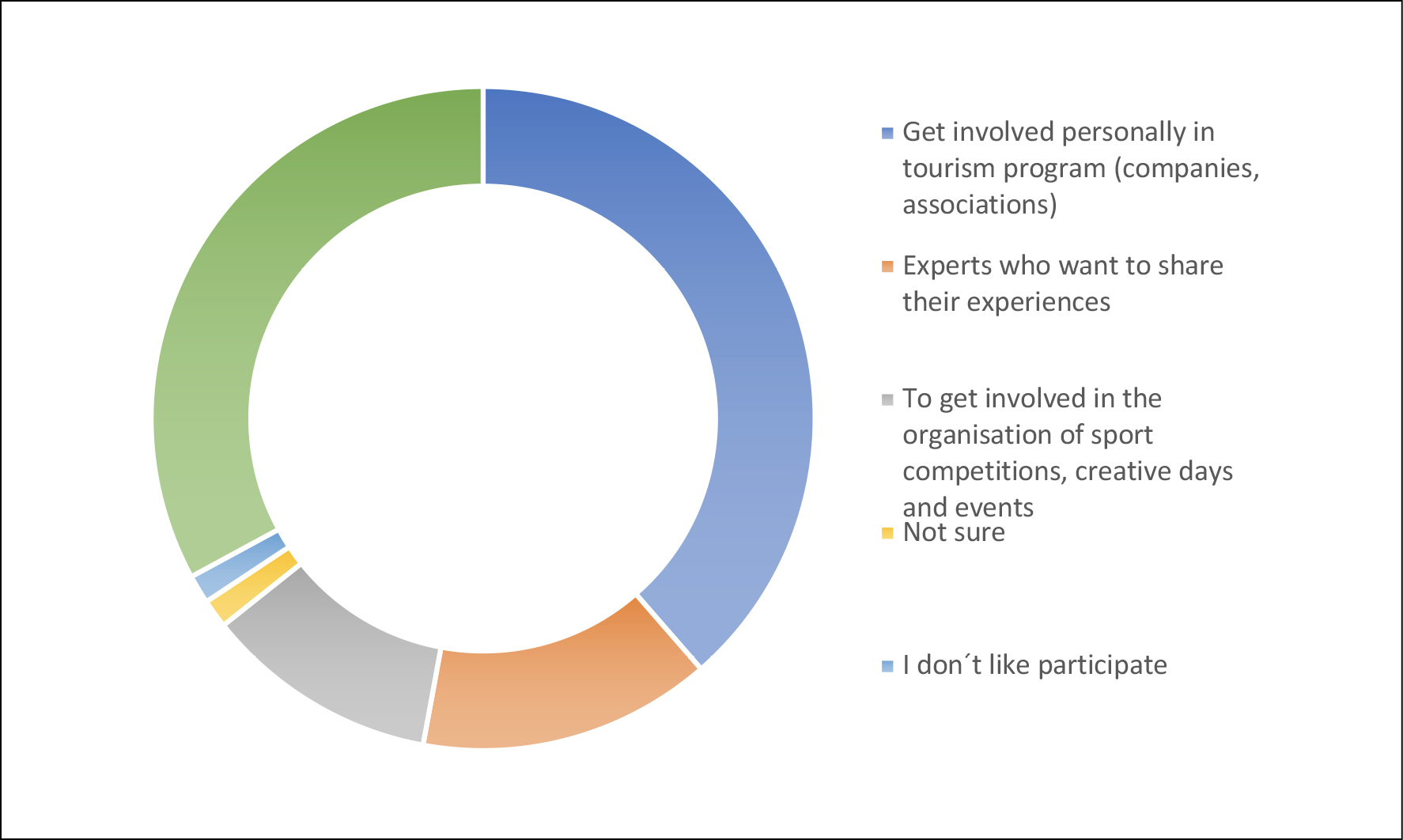

Moreover, when asked if they would be willing to participate in projects to promote comprehensive tourism development, the majority answered “Yes” (38.6%), with (14.3%) responding that they would like to participate by sharing their experiences as experts in the tourism sector and (11.4%) willing to participate in an ad hoc basis in the organisation of events, creative days or competitions. In addition, there was a minority who did not know how they could participate. Moreover, almost a third of respondents did not answer this question (32.9%) and a small percentage said they did not want to participate (figure 5).

Figure 5. Prefers to participate in tourism development projects. Source: own elaboration based on the survey results.

When analysed by age group (Annex IV), a majority of those aged 51 and above were interested in being personally involved in promoting tourism development projects, however, the 36-50 age segment represented less than half (41.7%) and only a quarter of the under 35 age group. By gender (Annex V), men (42.9%) were more willing to personally participate in tourism development projects than women (34.3%) with almost 8 percentage points difference. On the other hand, women (17.1%) showed more interest in participating by sharing their experiences as experts in the tourism sector with almost 6 percentage points difference compared to men (11.4%). Finally, there is equal interest in participating in the organisation of competitions, creative days and events among men and women (11.4%). According to education, 50% of those with primary and secondary education were interested in being personally involved in promoting tourism development projects and 16.7% would like to participate in the organisation of competitions, creative days and other events. Among those with university studies, 27% were interested in being personally involved in promoting tourism development projects, 15.6% would like to be involved in tourism planning as experts and 10.9% would like to be involved in the organisation of competitions, creative days and other events.

Table 2, which represents the socio-demographic characteristics of Ehden’s tourists, shows that women are more represented than men with 19 percentage points of difference. It is also worth noting that 1% of tourists chose not to provide information on their gender, which is unusual in Lebanon and has been considered neutral gender.

When analysed by age group, tourists aged 21-35 are over-represented in the sample with 77% of respondents. This is followed by the 36-50 age group with 19%. Far behind is the above 51 age group with only 4% of respondents. These results show that the tourists who choose this destination are quite young.

In terms of education, most of the tourists consulted have a university education (88%), 9% have a higher education (master’s or PhD) and only 3% have primary or secondary education.

Table 2. Summary of tourists’ profile.

|

Variables |

Categories |

% |

Variables |

Categories |

% |

|

Gender |

Female |

59% |

Occupation |

Student |

16% |

|

Male |

40% |

Domestic work |

4% |

||

|

Prefer not to say (Neutral) |

1% |

||||

|

Age |

21-35 |

77% |

Working |

72% |

|

|

36-50 |

19% |

Unemployed |

6% |

||

|

>51 |

4% |

Retired |

2% |

||

|

Residence |

Lebanon |

77.9% |

Education Level |

Primary/Secondary School |

3% |

|

Abroad |

22.1% |

University Studies |

97% |

Source: own elaboration based on the survey results. |

Tourists from Lebanon accounted for 77.9% of respondents and foreign tourists for 22.1%. The main countries of residence or countries of origin of foreign tourists are KSA and France (26.7% each one), followed by Australia (13.3%), Canada, USA, UAE, Qatar and Spain (6.7% each one) (Annex VII).

In order to understand the characteristics of tourism in Ehden, tourists were asked about the type of tourism activities they completed during their visit to Ehden, what type of events or shows they attended, what type of accommodation they chose, how long and when they travelled, and whether they would like to visit Ehden again.

When tourists were asked about their main motivations for visiting Ehden, it was found that green and adventure tourism were the most important motivations (86.8%) because most tourists consider Ehden to be a nature and adventure paradise. This is understandable, as one of the most significant sites is the Horsh Ehden Nature Reserve. This is followed by gastronomic tourism (64.7%), which has a long tradition in the region, and cultural tourism (64.7%). In addition, religious and/or spiritual tourism (60.3%) is also very relevant, as Ehden is famous for its churches and monasteries that invite spirituality. Finally, luxury and spa tourism plays an important role in Ehden (19.1%) (figure 6).

When analysed by age, all age groups showed the highest interest in green and adventure tourism, followed by gastronomic and cultural tourism and then religious tourism. However, the 35-50 age group showed the most interest in this motivation, and the 51 and above age group showed the least interest. Luxury and spa tourism was of greatest interest to the over 50s and of least interest to the under 35s (Annex VIII).

When analysed by gender, both groups were interested in green and adventure tourism, followed in the case of women by cultural, gastronomic and religious tourism. Men chose gastronomic tourism in second place, religious tourism in third place and cultural tourism in fourth place. Luxury and spa tourism came last, although there was slightly more interest from women. Neutral gender chose green and adventure tourism, cultural tourism and religious and spiritual tourism at the same level (Annex IX).

In terms of education, the Higher Education Group showed more interest in cultural tourism, followed by green and adventure tourism, gastronomic tourism, religious and spiritual tourism and, lastly, luxury tourism and spa. University students were most interested in green and adventure tourism, followed by gastronomic tourism and religious and spiritual tourism at the same level, then cultural tourism and finally luxury tourism and spa. Primary/Secondary School students showed the most interest in gastronomic tourism and secondly in green and adventure tourism, followed by cultural tourism. This group showed no interest in religious and spiritual tourism or luxury tourism and spa (Annex X).

Tourists were also asked which events and shows are of the most interest in Ehden (figure 6), detecting that all respondents were interested in Ehdeniyat International Festivals (100%), followed by gastronomic events such as Kebbeh Events (37%), sport events such as the Automobile et Touring Club du Liban (ATCL) or Lebanon Mountain Trail (LMT) (25%), book fairs (12%), Hiking Events (3%) or other unspecified events (3%) (figure 7).

Next, they were asked about the duration of their stay in Ehden, finding that a majority of tourists spend the whole summer in this locality (71%), which denotes a strong seasonal tourism, and a quarter spend a couple of days or weekends (25%), which associates it with a destination of rest and disconnection relatively close to the cities for a weekend. Finally, only 1% would spend a week in Ehden, with daily-trips accounting for 3% of all respondents.

When tourists were asked if they would visit Ehden again, the responses were very divided, with only 29.9% being clear that they would like to come back. 35.4% said they would not return and 34.7% said they might.

The majority of respondents prefer to stay in high quality accommodations like a hotel of 5-4 stars and Luxury Guest Houses (58.8%) when they travel, followed by those who prefer tourist apartments with 20,6%, hotels with less than 4 stars (19.1%) and their own house 1.5% (table 3).

Figure 6. Types of tourism in Ehden. Source: own elaboration based on the survey results.

Figure 7. Events and shows of interest in Ehden. Source: own elaboration based on the survey results.

Table 3. Type of accommodation preferred by tourists.

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Apartments (Airbnb and others) |

14 |

20.6 |

20.6 |

20.6 |

|

Hotels (less than 4 stars) |

13 |

19.1 |

19.1 |

39.7 |

|

|

High-quality accommodations Hotel (4-5 stars) and Luxury Rural Hotel |

40 |

58.8 |

58.8 |

98.5 |

|

|

Own house |

1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

68 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: own elaboration with SPSS based on the survey results. |

The Lebanese tourism model and therefore the origin of tourism in Ehden comes from the time when it was a French colony (Santer, 2019). Therefore, it was to be expected that it would resemble a very westernised tourism model (Winter, 2009) given that the origin of tourism and its expansion to the world also comes from the West (Cohen, 2008). This is confirmed by the fact that the most important activities are green and adventure tourism, followed by cultural and gastronomic tourism, with an important representation of luxury tourism and spas. This is complemented by contrived attraction resources such as music festivals, sporting events and other activities, similar to the type of activities that attract the interest of the European tourists (McKercher & Decosta, 2007), who are increasingly focused on leisure and enjoyment rather than cultural authenticity and learning as the main reason for travelling (Cohen, 2008). However, it is worth noting that people with higher education have shown an interest in cultural tourism over the rest of the proposed categories. Moreover, religious and spiritual tourism plays a very important role in this territory and shows that the coexistence of religions, churches and sanctuaries has become an important focus of attraction to this area. This differs markedly from western interests, since in the west religious and spiritual tourism has evolved into tourism for recreation and reconnection with oneself, which may or may not take place in destinations with a rich religious base (Palma, 2020).

Likewise, the most valued accommodations by tourists are high-quality hotels with the kind of facilities and services that, while previously intended for luxury tourism, are now widely offered in the west (Torres et al., 2014). While it might be expected that such high-quality hotels would be in the hands of foreign owners or hotel chains, and therefore a significant share of tourism revenues would remain in foreign hands, it has been found in consultations with local stakeholders that most of these hotels are run by local Lebanese inhabitants and were built in the 1990s. The similarities with the European model of accommodation can therefore be related to the fact that settler’ culture tends to permeate for several generations in former colonies and that the main flows of foreign tourists usually come from the country where they were settlers due to historical links (McKercher & Decosta 2007) as evidenced by the significant proportion of French tourists who account for 26.7% of foreign tourists. However, most of the current tourists are nationals, since international tourism has been contained as a result of the economic and political crash that Lebanon has suffered since 2019 and the COVID19 pandemic.

The fact that in Ehden the most demanded type of accommodation is high-end hotels is worrying. These types of hotels are the most consumptive accommodations in terms of land occupation, water and energy consumption, wastewater generation and waste. This is a clear symptom that the requirements of tourist accommodation are not in line with sustainable tourism (Nicholas et al., 2009).

On the other hand, it is obvious that the existing tourism model in Ehden is highly seasonal, concentrated during summer (mostly between July and September) and some weekends during the winter, which reproduces the Fordist model of mass tourism concentrated in a specific period (Marchena, 1994; Garay, 2007), although, in this case, it is in an inland destination.

Stakeholders also reported that there are very few services for the local population, whereas most of which are geared towards satisfying tourism and operate only during the summer or weekends, so that most of the population has opted to move to Zgharta during the winter, leaving very few families staying in Ehden on a permanent basis. This is a symptom of the “destination’s touristification” along the lines of the research done by Honey (2008) and Tosun (2000), that exposed it as a symptom for destinations, where resources and services are not used by the local population as a whole (Briasoulis, 2002). However, the climate also plays a role in this relocation, as it is harder to live in mountainous conditions rather than on the coast.

The results also show the poor sustainability of Ehden’s tourism model and contradict the fact that the most demanded activities are green and adventure tourism, since green tourism is normally related to ecotourism and promotes a model of enjoyment, protection and conservation of the environment, together with the improvement of the wellbeing of local communities (Higham, 2007; Pérez, 2022). However, in the case of Ehden, the concept of green tourism has been distorted (Rozzi et al., 2010), resembling a more touristic model of enjoyment in nature (nature as a backdrop) rather than of enjoyment and enhancement of nature.

On the other hand, the majority of the population is enthusiastic about getting involved in the promotion of a comprehensive tourism development model in Ehden based on a territorial brand image. In addition are those interested in participating as experts sharing their tourism experiences and those who would be willing to get involved in the promotion of festivals, fairs and sporting events. However, it should be noted that more than a third of those consulted did not answer this question or were not interested in getting involved in a project of such characteristics, meaning their motivations need to be explored in greater depth. However, it would be necessary to analyse how to implement a comprehensive tourism development model associated with a brand image for a territory that already shows symptoms of saturation, touristification and environmental unsustainability, so that the problems detected are not exacerbated. This has been stated by various researchers who have increasingly noted the opportunistic nature of the tourism industry, which gobbles up and commodifies all destinations and varieties of travel (Cohen, 2008). The idea proposed to boost Ehden’s tourism development is in line with research by Aguirre et al. (2018) and Kastenholz & Lima (2012), which show that for tourism to have a positive impact on the economy and society in the long term, it is necessary to develop a territorial planning model that values endogenous resources and recovers traditional activities, and in which sustainable and balanced tourism is just another complementary activity. However, care must be taken in territories with symptoms of touristification that should opt for either tourist containment (Mendoza-de-Miguel et al., 2020) or decrease (Andriotis, 2018; Milano et al., 2020) at least in the peak tourist seasons.

On the other hand, continuing with an unplanned, resource-consuming and waste-generating tourism model would go against the need to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the fight against climate change, and would be a model with low resilience, making it highly vulnerable to changes such as pandemics or adverse climatic situations, as explained by Bec et al. (2015).

Nevertheless, tourism businesses are still managed by local people, demonstrating that tourism revenues remain in local hands. However, large enterprises are often dominated by a small part of the privileged population. And it is important to stress that the effects of tourism affect all local people, so solutions must be based on the needs of the population as a whole. This includes restoring their endogenous activities and improving their infrastructure and facilities by incorporating a model of retributive justice (Jamal & Camargo, 2012; Alisa & Ridho, 2020).

This research shows that the legacy of a colonial tourism model oriented towards the needs of tourists and not towards the needs of the local population has resulted in Ehden having a “touristified” territory. Many of the traditional activities and services of the local population have been lost, orienting the local population and the territory exclusively towards the needs of tourists, who have appropriated it and the resources it provides.

The Ehden model has aspects that show that it is not a model of sustainable tourism, as it was not structured on the basis of the development and enhancement of endogenous resources, but rather by promoting leisure and entertainment activities. Moreover, tourism in Ehden does not take into account environmental conservation, is highly seasonal due to the concentration of demand during the summer and some weekends, and focuses on high quality accommodation which is the most resource-consuming (water, energy, soil) and generates wastewater and waste. However, there is great interest on the part of local actors and the population to promote an integrated tourism model in Ehden that would correct the deficiencies detected and have a positive impact on the local population.

As in many western countries, where the opportunistic nature of the tourism industry is increasingly evident, Ehden is aware of the limitations of tourism as the sole engine of economic development and of the problems generated by a totally tourism-oriented development model. Proof of this is that the local corporation and the majority of the population are committed to an integrated tourism development model through the creation of a territorial brand that will solve the problems detected and improve the image of this tourist destination.

The limitations of this research are related to the lack of availability of national data and statistics on the population and tourism and the fact that most of the interviews and surveys were conducted during the COVID19 pandemic and post-pandemic period (2021-2023), which slowed down the collection of information.

As a prospective, it would be necessary to propose a research model that would make it possible to study the needs of the Ehden population in depth and to collect proposals for recovering traditional socio-economic activities and introducing new ones that would serve as a lever to promote endogenous socio-economic development in Ehden for all the inhabitants, in which tourism would cease to be the predominant activity. It would also be necessary to study the possible mechanisms that can be implemented in Ehden to reduce seasonality, diversify the type of accommodation and improve the sustainability of existing accommodation.

This research received no specific grants or funding from any agency in the public, commercial or nonprofit sectors

The stakeholders and residents of Ehden were thanked for their willingness to participate in this research.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in relation to the publication of this article and that: a) they are the authors/coordinators of this article; b) they have the publishing rights to all images, photos and other graphic material that are part of the manuscript; c) as author/coordinator, they are the authors of this article:

Aguirre Bertel, A.M., Arroyo Oviedo, L.P., & Navarro Mesa, C.I. (2018). Turismo alternativo como estrategia de desarrollo local en el municipio de Chalan–Sucre. Económicas Cuc, 39(1). https://doi.org/10.17981/econcuc.39.1.2018.08

Alaoui, Y., & Abba, R. (2019). The R(Evolution) of Territorial Marketing: Towards an Identity Marketing. Journal of Marketing Research and Case Studies, 944163. https://doi.org/10.5171/2019.944163

Alisa, F., & Ridho, Z. (2020). Sustainable cultural tourism development: A strategic for revenue generation in local communities. https://assets.pubpub.org/73pjhgxv/21582062367058.pdf

Andriatis, K. (2002). Scale of hospitality firms and local economic development—evidence from Crete. Tourism Management, 23(4), 333-341.

Andriotis, K. (2018). Degrowth in tourism: Conceptual, theoretical and philosophical issues.

Aslan, A. (2013). Tourism development and economic growth in the Mediterranean countries: Evidence from panel Granger causality tests. Current issues in Tourism, 17(4), 363-372. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.768607

Bec, A., McLennan, C.L., & Moyle, B.D. (2015). Community resilience to long-term tourism decline and rejuvenation: A literature review and conceptual model. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(5), 431-457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1083538

Bessière, J. (1998). Local Development and Heritage: Traditional Food and Cuisine as Tourist Attractions in Rural Areas. Sociologia Ruralis, 38(1), 21-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00061

Blake, A., Sinclair, M.T., & Soria, J.A. (2006). Tourism productivity: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(4), 1099-1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.001

Bou Dager-Kharrat, M.E., & Rouhan, G. (2018). Setting conservation priorities for Lebanese flora—Identification of important plant areas. Journal for Nature Conservation, 43, 85-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2017.11.004

Buccianti-Barakat, L. (2006). Tourisme et développement au Liban: un dynamisme à deux vitesses. Téoros Revue de Recherche en Tourisme, 32-39. https://journals.openedition.org/teoros/1459#tocto1n5

Capello, R. (2019). Interpreting and understanding territorial identity. Regional science policy & Practice, 11(1), 141-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12166

Carneiro, M.J., Lima, J., & Silva, A.L. (2015). Landscape and the rural tourism experience: identifying key elements, addressing potential, and implications for the future. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8-9), 1217-1235. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1037840

Chambers, E. (2009). From authenticity to significance: Tourism on the frontier of culture and place. Futures, 41(6), 353-359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2008.11.003

Cohen, E. (2008). The changing faces of contemporary tourism. Society, 45(4), 330-333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-008-9108-2

Csete, M., & Szécsi, N. (2015). The role of tourism management in adaptation to climate change–a study of a European inland area with a diversified tourism supply. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(3), 477-496. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.969735

Devine, J., & Ojeda, D. (2017). Violence and dispossession in tourism development: A critical geographical approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 605-617. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1293401

Dinis, I., Simões, O., Cruz, C., & Teodoro, A. (2019). Understanding the impact of intentions in the adoption of local development practices by rural tourism hosts in Portugal. Journal of Rural Studies, 72, 92-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.10.002

Duro, J.A., Perez-Laborda, A., Turrion-Prats, J., & Fernández-Fernández, M. (2021). Covid-19 and tourism vulnerability. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100819

Ekanayake, E.M. and Long, & Aubrey E. (2012). Tourism Development and Economic Growth in Developing Countries, The International Journal of Business and Finance Research, 6(1), 61-63, 2012. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1948704

Garay Tamajón, L. A. (2007). El ciclo de evolución del destino turístico: una aproximación al desarrollo histórico del turismo en Cataluña. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/tesis/2007/tdx-1031107-162244/lagt1de1.pdf

Grant, R.M. (1994). L’analisi strategica nella gestione aziendale, il Mulino.

Henry, E., & Deane, B. (1997). The contribution of tourism to the economy of Ireland in 1990 and 1995. Tourism Management, 18(8), 535-553. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(97)00083-6

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2022). The ongoingness of imperialism: The problem of tourism dependency and the promise of radical equality. Annals of Tourism Research, 94, 103382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103382

Higham, J.E. (Ed.). (2007). Critical issues in ecotourism: Understanding a complex tourism phenomenon. Routledge.

Honey, M. (2008). Setting standards: certification programmes for ecotourism and sustainable tourism. In Ecotourism and Conservation in the Americas (pp. 234-261). Wallingford UK: CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845934002.0234

Hubbard, P., & Lilley, K. (2000). Selling the past: Heritage-tourism and place identity in Stratford-upon-Avon. Geography 85(3), 221–232. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40573703

Hummelbrunner, R., & Miglbauer, E. (1994). Tourism promotion and potential in peripheral areas: The Austrian case. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2(1-2), 41-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589409510682

Jamal, T., & Camargo, B.A. (2014). Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: Toward the just destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(1), 11-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.786084

Kastenholz, E., & Lima, J. (2012). The integral rural tourism experience from the tourist’s point of view–a qualitative analysis of its nature and meaning. Tourism & Management Studies, 7, 62-74. https://www.tmstudies.net/index.php/ectms/article/view/335/553

Kothari, U. (2015). Reworking colonial imaginaries in post-colonial tourist enclaves. Tourist Studies, 15(3), 248-266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797615579566

Lee, C.C., & Chang, C.P. (2008). Tourism development and economic growth: A closer look at panels. Tourism Management, 29(1), 180-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.02.013

L’Espoir Decosta, J.N.P. (2011). The colonial legacy in tourism: a post-colonial perspective on tourism in former island colonies [Doctoral disertation, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University]. Institutional repository The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. https://theses.lib.polyu.edu.hk/bitstream/200/6164/1/b24562336.pdf

Magnan, A., Hamilton, J., Rosselló, J., Billé, R., & Bujosa, A. (2013). Mediterranean tourism and climate change: Identifying future demand and assessing destinations’ vulnerability. Regional Assessment of Climate Change in the Mediterranean: Volume 2: Agriculture, Forests and Ecosystem Services and People, 337-365.

Marchena Gómez, M. J. (1994). Un ejercicio prospectivo: de la industria del turismo” fordista” al ocio de producción flexible. Papers de turisme, 14-15, 77-94. https://idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/47162/417-1875-1-PB.pdf?sequence=1

McKercher, B., & Decosta, P. L. E. (2007). The lingering effect of colonialism on tourist movements. Tourism Economics, 13(3), 453-474. https://campus-fryslan.studenttheses.ub.rug.nl/id/eprint/180

McKinnon, R. I. (1964). Foreign Exchange Constraints in Economic Development and Efficient Aid Allocation. The Economic Journal, 47(294), 388-409. https://doi.org/10.2307/2228486

Mendoza-de-Miguel, S., Ferreiro-Calzada, E., Calle-Vaquero, M., & de la García Hernández, M. (2020). “Overtourism” en centros urbanos. ¿Qué opinan los técnicos de la administración local? In G.X. Pons, A. Blanco-Romero, R. Navalón-García, L. Troitiño-Torralba, & M. Blázquez-Salom (Eds.), Sostenibilidad Turística: Overtourism vs Undertourism, (pp. 319-329). https://ibdigital.uib.es/greenstone/sites/localsite/collect/monografiesHistoriaNatural/index/assoc/Monograf/iesSHNB_/2020vol0/31p319.dir/MonografiesSHNB_2020vol031p319.pdf

Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J. M. (2020). Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective. In Tourism and Degrowth (pp. 113-131). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1650054

Minguzzi, A., & Presenza, A. (2010). Destination building. Teorie e pratiche per il management della destinazione turistica. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Nicholas, L. N., Thapa, B., & Ko, Y. J. (2009). RESIDENTS’PERSPECTIVES OF a world heritage site: The pitons management area, st. Lucia. Annals of tourism research, 36(3), 390-412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.03.005

Ou, Y., & Bevilacqua, C. (2017). From Territorial Identity to Territorial Branding: Tourism-Led Revitalization of Minor Historic Towns in Reggio Calabria. Management of World Heritage Sites, Cultural Landscapes and Sustainability. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Palma Hernández, R. (2019). Turismo espiritual: ¿una moda pasajera o una práctica permanente en el viajero de hoy? http://hdl.handle.net/11201/151084

Paasi, A. (2003). Region and place: regional identity in question. Progress in Human Geography, 27(4), 475-485. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132503ph439p

Pérez, B. P. (2022). Turismo sostenible, ecoturismo y la CETS: Sierra Nevada (España). HUMAN REVIEW. International Humanities Review/Revista Internacional de Humanidades, 12(6), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.37467/revhuman.v11.3995

Pollice, F., Claval, P., Pagnini, M. P., & Scaini, M. (2003). The role of territorial identity in local development processes. In Part II: Landscape Construction and Cultural Identity. https://www.openstarts.units.it/server/api/core/bitstreams/ef3f0c9a-5cac-4db0-876d-0b0247cad8a0/content

Poussin, A., & Poussin, S. (2009). Africa trek II: 14,000 kilometers in the footsteps of mankind: From mount kilimanjaro to the sea of galilee. Inkwater Press.

Roca, Z., & de Nazaré Oliveira-Roca, M. (2007). Affirmation of territorial identity: A development policy issue. Land Use Policy, 24(2), 434-442. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.landusepol.2006.05.007

Romão, J. (2021). Nature, Tourism, Growth, Resilience and Sustainable Development. Mediterranean Protected Areas in the Era of Overtourism: Challenges and Solutions, 297-310. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69193-6_15

Rozzi, R., Massardo, F., Cruz, F., Grenier, C., Muñoz, A., Mueller, E., & Elbers, J. (2010). Galápagos and Cape Horn: ecotourism or greenwashing in two iconic Latin American Archipelagoes? Environmental Philosophy, 7(2), 1-32. https://shorturl.at/frEK6

Santer, J. S. (2019). Imagining Lebanon: Tourism and the production of space under French Mandate (1920-1939) (Doctoral dissertation, American University of Beirut). American University of Beirut. https://scholarworks.aub.edu.lb/bitstream/handle/10938/21811/t-7056.pdf?sequence=1

Sattout, E.J. (2009). Terrestrial flora diversity in Jabal Moussa: Preliminary biodiversity assessment and site diagnosis. Beirut. https://www.jabalmoussa.org/sites/default/files/13-%20Terrestrial%20Flora%20Diversity_SiteDiagnosis_Sattout%26Molina_2009.pdf

Simon, C., Huigen, P.P., & Groote, P. (2010). Analysing Regional Identities in the Netherlands. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 101(4), 409-421. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2009.00564.x

Solima, L., & Minguzzi, A. (2014). Territorial development through cultural tourism and creative activities. Mondes du Tourisme, 10, 6-16. https://doi.org/10.4000/tourisme.366

Spilanis, I., & Vayanni, H. (2004). Sustainable tourism: utopia or necessity? The role of new forms of tourism in the Aegean Islands. Coastal mass tourism: Diversification and sustainable development in Southern Europe, 269-291. https://doi.org/ 10.21832/9781873150702-015

Stoffelen, A., Groote, P., Meijles, E., & Weitkamp, G. (2019). Geoparks and territorial identity: A study of the spatial affinity of inhabitants with UNESCO Geopark De Hondsrug, The Netherlands. Applied Geography, 106, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2019.03.004

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088148

Torres Bernier, E., Ramírez Sánchez, R., & Rodríguez Díaz, B. (2014). La crisis económica en el sector turístico. Un análisis de sus efectos en la costa del Sol. Revista de análisis turístico, 18(2), 11-18. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4983222

Tosun, C. (2000). Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management, 21(6), 613-633. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00009-1

Williams, T. R. (2012). Tourism as a neo-colonial phenomenon: examining the works of Pattullo & Mullings. Caribbean Quilt, 2, 191-200. https://doi.org/10.33137/caribbeanquilt.v2i0.19313

Winter, T. (2009). Asian tourism and the retreat of anglo-western centrism in tourism theory. Current Issues in Tourism, 12(1), 21-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500802220695

World Travel and Tourism Council, WTTC (2016). Global travel and tourism economic impact update. WTTC. https://www.arab-tourismorg.org/images/pdf/World2016.pdf

In line with the local authority’s idea of improving the conservation of the natural, cultural and religious heritage and promoting tourism around all territorial resources Would you like/would you agree with the implementation of a comprehensive tourism development model in Ehden?

How would you like to participate in the development of a comprehensive tourism model for Ehden?

What are your main motivations for visiting Ehden?

What type of events or shows did you attend?

What type of accommodation have you chosen?

How long will you spend in Ehden?

|

How would the local population participate in tourism development in Ehden |

|||||||||

|

The initiatives |

Total |

||||||||

|

No answer |

Get involved personally (businesses, associations |

Experts who want to participate in tourism management and planning |

I don’t know how |

I don’t like to participate |

To get involved in the organisation of competitions, creative days and events |

||||

|

Group age |

Under 35 |

Count |

16 |

9 |

8 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

35 |

|

% within group age |

45.7% |

25.7% |

22.9% |

2.9% |

0.0% |

2.9% |

100.0% |

||

|

36-50 |

Count |

7 |

10 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

24 |

|

|

% within group age |

29.2% |

41.7% |

8.3% |

0.0% |

4.2% |

16.7% |

100.0% |

||

|

Above 51 |

Count |

0 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

11 |

|

|

% within group age |

0.0% |

72.7% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

27.3% |

100.0% |

||

|

Total % within group age |

Count |

23 |

27 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

70 |

|

|

32,9% |

38.6% |

14.3% |

1.4% |

1.4% |

11.4% |

100.0% |

Source: own elaboration based on the survey. |

||

|

How would the local population participate in tourism development in Ehden |

|||||||||

|

The initiatives |

Total |

||||||||

|

No answer |

Get involved personally (businesses, associations |

Experts who want to participate in tourism management and planning |

I don’t know how |

I don’t like to participate |

To get involved in the organisation of competitions, creative days and events |

||||

|

Gender |

Female |

Count |

13 |

12 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

35 |

|

% within Gender |

37.1% |

34.3% |

17.1% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

11.4% |

100.0% |

||

|

Male |

Count |

10 |

15 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

35 |

|

|

% within Gender |

28.6% |

42.9% |

11.4% |

2.9% |

2.9% |

11.4% |

100.0% |

||

|

Total % within Gender |

Count |

23 |

27 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

70 |

|

|

32,9% |

38.6% |

14.3% |

1.4% |

1.4% |

11.4% |

100.0% |

Source: own elaboration based on the survey. |

||

|

How would the local population participate in tourism development in Ehden |

||||||||

|

The initiatives |

Total |

|||||||

|

No answer |

Get involved personally (businesses, associations) |

Experts who want to participate in tourism management and planning |

I don’t know how |

I don’t like to participate |

To get involved in the organisation of competitions, creative days and events |

|||

|

Primary/Secondary School |

Count |

2 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

|

% within EL |

33.3% |

50.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

16.7% |

100.0% |

|

|

University |

Count |

21 |

24 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

64 |

|

% within EL |

32.8% |

37.5% |

15.6% |

1.6% |

1.6% |

10.9% |

100.0% |

|

|

Total |

Count |

23 |

27 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

70 |

|

% within EL |

32.9% |

38.6% |

14.3% |

1.4% |

1.4% |

11.4% |

100.0% |

Source: own elaboration based on the survey. |

|

Residency of abroad tourist |

|||||

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Australia |

2 |

2.9 |

13.3 |

13.3 |

|

Canada |

1 |

1.5 |

6.7 |

20.0 |

|

|

France |

4 |

5.9 |

26.7 |

46.7 |

|

|

KSA |

4 |

5.9 |

26.7 |

73.3 |

|

|

Qatar |

1 |

1.5 |

6.7 |

80.0 |

|

|

Spain |

1 |

1.5 |

6.7 |

86.7 |

|

|

UAE |

1 |

1.5 |

6.7 |

93.3 |

|

|

USA |

1 |

1.5 |

6.7 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

15 |

22.1 |

100.0 |

||

|

Missing |

0 |

53 |

77.9 |

||

|

Total |

68 |

100.0 |

|||

|

Residency of all tourist |

|||||

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Australia |

2 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

|

Canada |

1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

4.4 |

|

|

France |

4 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

10.3 |

|

|

KSA |

4 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

16.2 |

|

|

Lebanon |

53 |

77.9 |

77.9 |

94.1 |

|

|

Qatar |

1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

95.6 |

|

|

Spain |

1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

97.1 |

|

|

UAE |

1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

98.5 |

|

|

USA |

1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

68 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: own elaboration based on the survey. |

|

|

AG |

Total |

|||||

|

Under 35 |

Between 35-50 |

Above 51 |

||||

|

Tourism Types |

Cultural |

Count |

32 |

10 |

2 |

44 |

|

% within Tourism Types |

72.7% |

22.7% |

4.6% |

|||

|

Gastronomy |

Count |

32 |

10 |

2 |

44 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

72.7% |

22.7% |

4.6% |

|||

|

Green and Adventure |

Count |

44 |

12 |

3 |

59 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

74.6% |

20.3% |

5.1% |

|||

|

Luxury and Spa |

Count |

9 |

3 |

1 |

13 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

69.2% |

23.1% |

7.7% |

|||

|

Religious and Spiritual |

Count |

30 |

10 |

1 |

41 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

73.2% |

24.4% |

2.4% |

|||

|

Total |

Count |

52 |

13 |

3 |

68 |

Source: own elaboration based on the survey. |

|

Gender |

Total |

|||||

|

Female |

Male |

Neutral |

||||

|

Tourism Types |

Cultural |

Count |

26 |

17 |

1 |

44 |

|

% within Tourism Types |

59.1% |

38.6% |

2.3% |

|||

|

Gastronomy |

Count |

24 |

20 |

0 |

44 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

54.5% |

45.5% |

0.0% |

|||

|

Green and Adventure |

Count |

35 |

23 |

1 |

59 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

59.3% |

39.0% |

1.7% |

|||

|

Luxury and Spa |

Count |

8 |

5 |

0 |

13 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

61.5% |

38.5% |

0.0% |

|||

|

Religious and Spiritual |

Count |

22 |

18 |

1 |

41 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

53.7% |

43.9% |

2.4% |

|||

|

Total |

Count |

40 |

27 |

1 |

68 |

Source: own elaboration based on the survey. |

|

EL |

Total |

|||||

|

Primary/Secondary School |

University |

Higher Education |

||||

|

Tourism Types |

Cultural |

Count |

1 |

36 |

7 |

44 |

|

% within Tourism Types |

2.3% |

81.8% |

15.9% |

|||

|

Gastronomy |

Count |

2 |

37 |

5 |

44 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

4.5% |

84.1% |

11.4% |

|||

|

Green and Adventure |

Count |

2 |

51 |

6 |

59 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

3.4% |

86.4% |

10.2% |

|||

|

Luxury and Spa |

Count |

0 |

10 |

3 |

13 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

0.0% |

76.9% |

23.1% |

|||

|

Religious and Spiritual |

Count |

0 |

37 |

4 |

41 |

|

|

% within Tourism Types |

0.0% |

90.2% |

9.8% |

|||

|

Total |

Count |

2 |

60 |

6 |

68 |

Source: own elaboration based on the survey. |