DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/rea.2023.i45.04

Formato de cita / Citation: Buitrago-Esquinas, E.M. et al. (2023). A literature review on overtourism to guide the transition to responsible tourism. Revista de Estudios Andaluces, (45), 71-90. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/rea.2023.i45.04

Correspondencia autores: ovando@us.es (Rocío Yñiguez-Ovando)

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Eva María Buitrago-Esquinas

esquinas@us.es  0000-0003-4113-5836

0000-0003-4113-5836

Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales. Universidad de Sevilla. Avenida Ramón y Cajal, 1. 41018 Sevilla, España.

Concepción Foronda-Robles

foronda@us.es  0000-0002-3632-2410

0000-0002-3632-2410

Facultad de Turismo y Finanzas. Universidad de Sevilla. Avenida San Francisco Javier, s/n. 41018 Sevilla, España.

Rocío Yñiguez-Ovando

ovando@us.es  0000-0002-7370-6632

0000-0002-7370-6632

Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales. Universidad de Sevilla. Avenida Ramón y Cajal, 1. 41018 Sevilla, España.

|

INFO ARTÍCULO |

ABSTRACT |

|

|

Received: 30/05/2022 Revised: 09/06/2022 Accepted: 16/12/2022 KEYWORDS Overtourism Conceptual framework Literature review Responsible tourism Covid-19 |

Although the pre-pandemic tourism debate was led by Overtourism, when the pandemic erupted, the increasing literature on this topic was still in an initial stage. The mobility restrictions derived from Covid-19 stopped Overtourism, but the problem is still far from being eradicated. There is an increasingly need for a solid body of knowledge on which to build recovery to avoid making past mistakes. A comprehensive pre-pandemic literature review is carried out, by proposing an overtourism conceptual framework that integrates its causes and consequences. How the pandemic could become an opportunity to transition to a responsible tourism model is discussed. |

|

|

PALABRAS CLAVE |

RESUMEN |

|

|

Overtourism Marco conceptual Revisión de literatura Turismo responsable Covid-19 |

El debate turístico previo a la pandemia estuvo protagonizado por el fenómeno del overtourism, con un crecimiento exponencial de la literatura científica. No obstante, en el momento de la irrupción del coronavirus, este topic aún estaba en un estadio inicial. Aunque las restricciones de movilidad derivadas del Covid-19 frenaron el overtourism, el problema está aún lejos de haberse erradicado. Hoy es más patente la necesidad de un cuerpo sólido de conocimientos sobre el cual construir la recuperación del sector, evitando cometer los errores del pasado. Este trabajo realiza una revisión exhaustiva de la literatura previa a la pandemia, proponiendo un marco conceptual para el análisis del overtourism que integra sus causas y consecuencias. Se discute cómo la pandemia podría convertirse en una oportunidad para la transición hacia un modelo de turismo responsable. |

The Covid-19 pandemic has paralysed the world and has caused immense human and economic losses. However, like all crises, it is an opportunity: this stoppage of activity can and should be employed to rethink the desirable tourist model for the future (Lew et al., 2020). The revival of the sector must be carefully planned and implemented in order to prevent the pre-pandemic overtourism situations from being repeated.

Before the pandemic, one of the hot topics in the tourism debate, especially in urban tourism, was overtourism. UNWTO (2018) defines overtourism as “the impact of tourism on a destination, or parts thereof, that excessively influences the perceived quality of life of citizens and / or the quality of visitors experiences negatively. (…) It is the opposite of Responsible Tourism, which is about using tourism to make better places to live in and better places to visit”(p. 4).

Although most of the issues underlying overtourism were not new to the sector (overcrowding, carrying capacity, destination irritation index, tourism area life cycle), additional nuances had emerged that required innovative formulae both for its scientific analysis and for those responsible for its management. Information and communication technology (ICT) and globalization modified not only the way of travelling, but also the business model (Boluk et al., 2019). Tourist flows grew exponentially and concentrated in certain places, mainly cities; this in turn generated overcrowding situations that damaged both the quality of life of the resident and the satisfaction of the tourist. The geopolitical context in which tourist activity takes place is becoming increasingly complex. The elements that make up the tourism system and the different agents that participate there are more connected and their relationships are more profound. Overtourism is a multidimensional phenomenon that must be tackled in a multidisciplinary way, by combining approaches that incorporate economics, geography, ecology, sociology, political science, and psychology.

Although scientific work on overtourism had increased in the previous pandemic years, no widely accepted conceptual framework had yet been established on which future studies could be based and through which those responsible for tourism management can support their decisions (Capocchi et al., 2020).

Since overtourism became a ‘fashionable’ term (Capocchi et al., 2019) in a significant part of the existing literature, it is often only mentioned in the introduction or in the conclusions as part of the pre-covid tourism problems. Besides, many studies that carried out specific analyzes of overtourism did so in a partial way and focused on a limited number of its causes and/or consequences (Del Chiappa et al., 2018; Milano et al., 2019). Certain literature reviews also exist, but again they are partial studies in which only a few of the dimensions associated with the term are analyzed (see, e.g., Dodds & Butler, 2019). Recently, theoretical conceptualization and modelling studies have begun to be published, which could be taken as the starting point for the rigorous analysis of the phenomenon (Mihalic, 2020; Nilsson, 2020; Wall, 2020). Our work belongs to this new line of research. Thus, an exhaustive review of the scientific literature earlier pandemic is carried out in order to contribute towards the development of a systematic and integrated conceptual framework that can guide the post-pandemic tourism model. Specifically, the following objectives are set out:

Our paper therefore makes a double contribution. On the one hand, it enriches the existing literature by systematising previous results and contributes towards the construction of an integrated conceptual framework for the analysis of overtourism. On the other hand, the results achieved in this paper could be significant for policy makers since they provide tools to handle overtourism. This can provide a key to overcoming past mistakes and to planning a suitable transition from pre-pandemic overtourism to a post-pandemic responsible tourism model.

This paper is structured as follows: This Introduction is followed by the description of the research method and sample profile; Section 3 proposes a conceptual framework for the analysis of overtourism, presented in pictorial form, from the literature review carried out; Section 4 discusses pre-pandemic alternatives for the management of overtourism; Section 5 presents the results and discusses how the pandemic can be converted into an opportunity for the transition to a post-pandemic responsible tourism model; and finally, a set of concluding remarks is laid out in Section 6.

This paper shows results through the collection, assessment, and integration of pre-pandemic scientific literature on overtourism. A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis (QIMS) of the existing literature on overtourism was carried out in order to bring to light the elements that characterize this complex and multidimensional phenomenon (Gough et al., 2013). As a non-linear conceptualization of a cross-study data collection tool, QIMS is intended to merge topics from a collection of related studies into a holistic understanding.

The papers have been reviewed and synthesized using in both deductive and inductive methods by determining a collection of linked overtourism features based on how they are applied in the literature. Therefore, the selected documents were coded in a double process: in a first stage, those codes recurring in the academic tourism literature were deductively determined; in a second phase, an inductive method was utilized, by extracting new codes from the particularized study of each of the papers in our sample. This codification has enabled a detailed analysis of the dimensions of overtourism discussed in the literature, which has served as the basis for the design, in pictorial form, of a holistic conceptual framework regarding the phenomenon.

Data for QIMS was collected through the use of purposive sampling to select relevant papers on overtourism. These studies were found using scientific databases, mainly those of the Web of Science and Science Direct. The search was then completed with Google Scholar. In addition, relevant publications were identified as they were cited in the publications under scrutiny. Keywords used in the search included different forms of writing ‘overtourism’ and, given its multidisciplinary character, the search tackled various areas of knowledge (sociology, geography, economics, politics, ecology and psychology). The search period ranged from 1990 to the onset of the covid-19 pandemic (early 2020).

The first search resulted in the collection of approximately 200 articles. After a filtering process, in which repeated documents and previous versions of the same work were excluded, the sample was reduced to 154 papers. A first screening of those documents was carried out largely based on abstracts and executive summaries to sort out irrelevant publications. In all, we collected 99 unique studies (see the complete list in the Supplementary Material).

According to the objectives of the work, the final sample was coded. Our coding framework was developed in an iterative process. Initial coding dimensions were developed deductively, based on the knowledge of the topic from the academic tourism literature: identification of the work; treatment of overtourism; type of paper; tourist typology and geographical area. Additional coding dimensions were added inductively throughout the coding process, based on the profound review of our sample. They were added to identify the topics related to overtourism addressed in the work: measurement (indicators, surveys, interviews, and social networks), causes (supply, demand, management), impacts (touristification, gentrification, degradation, and sociopsychological impacts), and management alternatives (integral planning, strategic goals and measures). An overview of the information of all the studies is available as Supplementary Material.

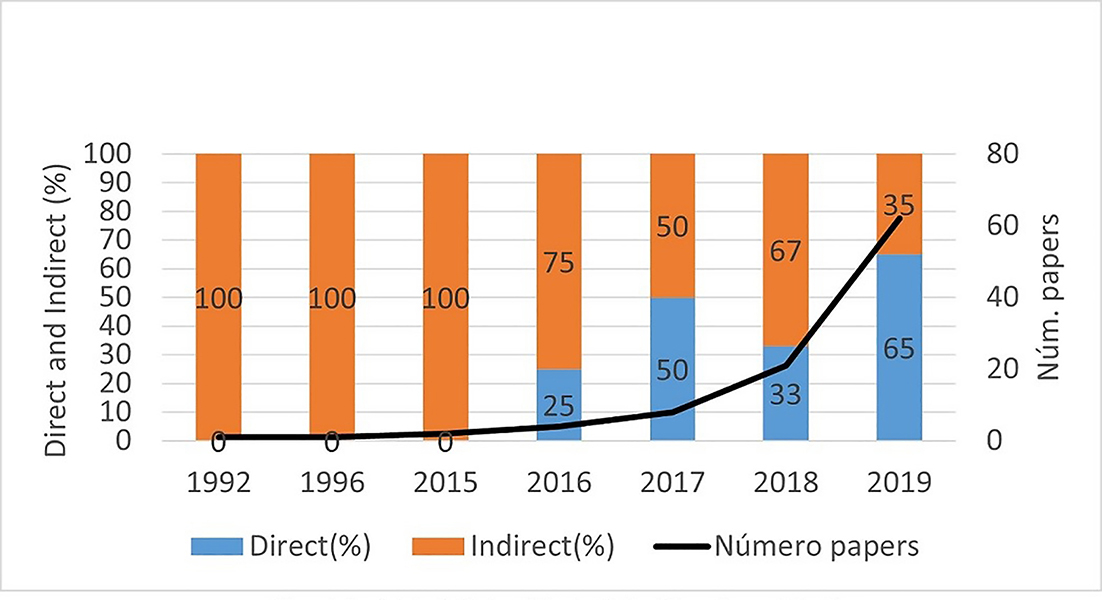

We observed that 80% of the papers had been published in the last two years of the period studied, which confirms that we are dealing with a term whose study is recent, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Trends in the Publication of Direct and Indirect Papers. Source: Authors´own.

Almost half of the selected papers refer to overtourism indirectly (49%) and, in many cases, overtourism is reduced to a mere quote in the introduction or in the conclusions as a cause or side effect of the main topic of the paper.

Although most of the work in the entire sample is empirical (55%), most of those who handle overtourism directly are theoretical and carry out partial analyzes focused on a number of the causes, consequences, and/or alternatives proposed in order to tackle the phenomenon. Only half of these studies that deal with overtourism directly include any type of measurement of overtourism. On the other hand, they are mostly case studies of specific cities (40%) and of these, 86% are located in Europe (figure 2).

Figure 2. Features of the sample of direct papers. Source: Authors´own.

The photography obtained from the pre-pandemic literature review shows that overtourism became a ‘fashionable’ word, which has been largely used in exploratory case studies, located mainly in European cities, and focused solely on one of the dimensions of overtourism. In fact, together with the deficiencies in the measurement of overtourism (Buitrago & Yñiguez, 2021), one of the main weaknesses of these studies is their partial focus.

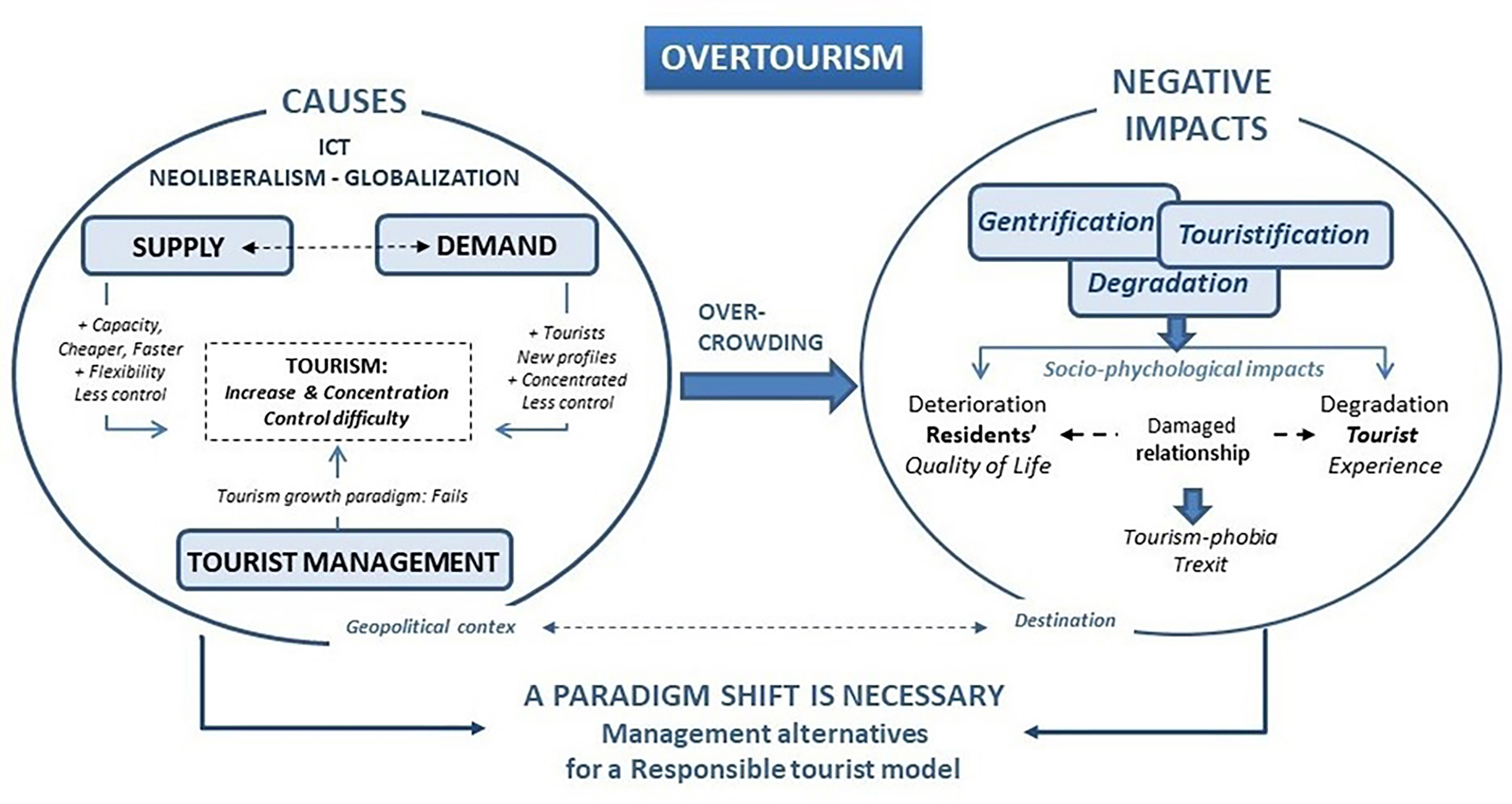

In order to overcome this lack of an all-encompassing approach, our work proposes an integrated conceptual framework design presented in pictorial form and based on the conclusions of the reviewed work. Although overtourism is a multidimensional concept that presents differential elements in each case, we have striven to group its possible causes and consequences through an integrated theoretical framework, focusing on its driving forces and on the new nuances that explain both the emergence of the phenomenon and the need for new multidisciplinary approaches to its scientific study and its management.

Despite the fact that the concept of sustainable tourism is widely consolidated theoretically (Butler, 1974; Inskeep, 1991), there are major shortcomings in its practical implementation. In fact, the very existence of overtourism situations is a clear reflection thereof. The term responsible tourism has been developed over the past decade (see, e.g., Goodwin, 2011) to expand the sustainable tourism paradigm by focusing not only on the theoretical pillars of sustainability, but also on the actions and behaviours necessary for its effective implementation. According to Mihalic (2020), in this work, the phenomenon of overtourism is analyzed in the conceptual framework of (ir)-responsible tourism, delving into the theories that support both its causes and its consequences.

In summary, and as shown in figure 3, the increasingly complex geopolitical contexts linked to the expansion of the neoliberal economic paradigm, ICT, and globalization, have accelerated changes both in the way of travelling and business models and in tourism policy (Boluk et al., 2019). Guided by these driving forces, tourist flows have grown exponentially, having concentrated both spatially and temporally, whereby the tourism industry is increasingly controlled by unregulated capital flows. Furthermore, tourism policy, focused on tourism growth strategies, has granted power to the private sector and has failed to react with sufficient speed and flexibility. Faced with this situation, tourists and residents compete for scarce resources, often in fragile environments, which has generated serious economic, social, environmental, and institutional impacts on destinations. Therefore, a major contradiction is revealed that can largely explain the difficulties in managing overtourism: While the causes are especially linked to the global scale, the impacts are focused on the local scale.

Figure 3. Integrated Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of Overtourism. Source: Authors´own.

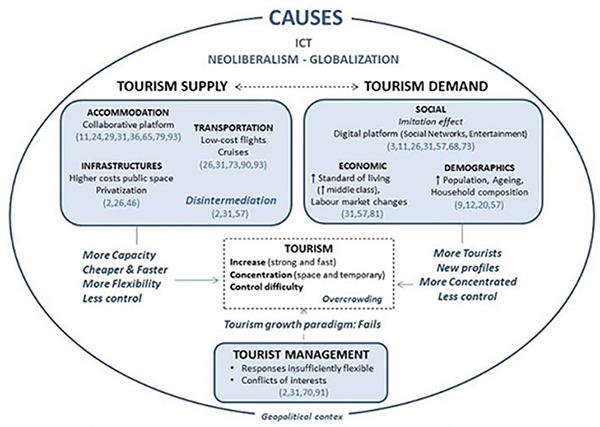

In figure 4, from the literature review carried out, the possible causes of overtourism (on the side of supply, demand, and tourism management) have been systematized by them in the underlying geopolitical context, and references to the paper that addressed these causes are given (the numbers in the figure correspond to the code of the reviewed papers).

Supply factors are strongly influenced by both technological advances and the neoliberal economic paradigm, which has generated profound changes throughout the tourist industry (accommodation, transport, infrastructure and intermediary sectors). The expansion of the internet has fostered a process of disintermediation in a large part of the tourism subsectors by reducing costs, making travel more flexible, and rendering tourism more difficult to control (Alexis, 2017). At the same time, the spread of neoliberalism and globalization has led to a tourism industry that is more highly susceptible to global capital flows (Bianchi, 2018) and more dependent on the global travel supply chain operating outside the destination communities (Milano et al., 2019). In accommodation, the most significant change is found in the rise of digital platforms that allow direct contact between hosts and tourists. Many residential homes are subject to tourist use, when they are rented and/or temporarily exchanged by their owners through platforms such as Airbnb, HomeAway, and Home Exchange (Sarantakou & Terkenli, 2019). The tourist can make the reservation directly, view the accommodation and even discover the experience of previous clients. This type of accommodation is more difficult to control than traditional tourism accommodation, making its expansion more complex to limit (Ghidouche & Ghidouche, 2019). This new business model has attracted large corporations and large investors by fostering intense real-estate speculation processes, especially in urban centres (González-Pérez, 2020). All this has markedly increased the supply of tourism accommodation and reduced its prices, making it possible for more tourists to concentrate in the same place at the same time, thereby causing overtourism and intensifying the gentrification process (Novy, 2019).

Transport is also responsible for this excess tourism, particularly low-cost airlines and large cruise ships. The liberalization of international aviation and the growing use of online distribution channels explain the profound change in the commercial models of air transport, dominated today by low-cost airlines. These airlines, by offering lower prices for more destinations, allow more people to travel to farther destinations (Dodds & Butler, 2019) and enable more short trips to be made throughout the year (Peeters et al., 2018). In turn, this increase in customers generates new price reductions, which again encourage more trips. The existence of low-cost flights has become a determining factor both in the decision to travel and in the choice of destination (Nilsson, 2020). On the other hand, large cruises allow an enormous number of tourists to visit destinations without having the limitation of having to stay there overnight. Accommodation at the destination no longer constitutes a limitation to tourist demand. Cruise tourists spend little time at each destination and visit only the most prominent attractions, which explains the large concentration of tourists in the same space at the same time (Seraphin et al., 2018). Furthermore, transport is another sector where collaborative economy platforms have appeared (BlaBlaCar, Uber, Cabify, shared bicycles or scooters, etc.) and have altered both ways of travelling and moving around (Novy, 19).

Likewise, overtourism is also explained by changes in the infrastructures that support such transport. The prevailing neoliberalism in the global economy has led to the privatization of certain infrastructures, making it more difficult to control tourist arrivals, since the interests of the owners are often in opposition to this control (Alexis, 2017).

In short, the tourist industry is currently less intermediated and is more flexible and varied, destinations are more accessible and affordable for tourists, there is greater accommodation capacity, and most importantly, the industry is more difficult to control (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Overtourism Conceptual Framework: Causes. Literature review. Note: The numbers in parentheses correspond to the code of the reviewed papers that deal with causes of overtourism. See references in Table A1 of the Appendix. Source: Authors´own.

On the demand side, a combination of demographic, economic, and social factors linked to the aforementioned driving forces have led to a sharp increase in tourism and the appearance of new consumption patterns that have contributed to the concentration of tourism in both space and time.

Demographic factors include the growth of the world’s population, the ageing of the population, and the appearance of increasingly diverse households. UNWTO (2013) points out that these trends affect both the number of tourists and the patterns of demand (frequency and duration of trips, products demanded, spending and tourist behaviour). Intergenerational differences and differences in the composition of households diversify the ways of travelling: millennials and baby boomers; singles or couples (heterosexual or homosexual); in family groups; or groups of friends. In general, the number of trips has increased and their duration has been shortened. These short-term trips are limited to visiting the main tourist attractions of the destination, thereby contributing towards its overcrowding (McKinsey & WTTC, 2017).

On the demand side, a combination of demographic, economic, and social factors linked to the aforementioned driving forces have led to a sharp increase in tourism and the appearance of new consumption patterns that have contributed to the concentration of tourism in both space and time.

Demographic factors include the growth of the world’s population, the ageing of the population, and the appearance of increasingly diverse households. UNWTO (2013) points out that these trends affect both the number of tourists and the patterns of demand (frequency and duration of trips, products demanded, spending and tourist behaviour). Intergenerational differences and differences in the composition of households diversify the ways of travelling: millennials and baby boomers; singles or couples (heterosexual or homosexual); in family groups; or groups of friends. In general, the number of trips has increased and their duration has been shortened. These short-term trips are limited to visiting the main tourist attractions of the destination, thereby contributing towards its overcrowding (McKinsey & WTTC, 2017).

Globalization of media and social networks has become an accelerator of this overcrowding process (Jang & Park, 2020). On the one hand, the internet and social networks offer new horizons regarding where to travel, what to visit, and how to live certain experiences, thereby generating a multiplier effect (Papathanassis, 2017). In this sense, digital social recommendation platforms, such as TripAdvisor, are an effective lever of persuasion in the stages of collecting information from consumers (Bourliataux-Lajoinie et al., 2019). All this opens up new horizons, but it also tends to focus visits on the most highly recommended destinations and attractions. Facebook, Instagram, and Pinterest further accelerate these processes through the so-called imitation effect. The publications posted on these networks by influencers create fads and trends with repercussions on millions of followers, who travel to the same place and at the same time to attain the same photo. Thus, as Nilsson (2020, p. 665) points out, “marketing power is shifting away from destinations toward an amorphous network of influencers and common users, managed by profit seeking algorithms”.

Similarly, globalization of the media and the entertainment industry contributes to this effect. Platforms, such as Netflix, HBO, and Amazon Prime, allow films and series to be seen around the world, thereby converting the settings where they are filmed into tourist attractions for millions of fans (Dodds & Butler, 2019). These trends occur with greater intensity with the Millennials; this generation is entering their peak-earning years and uses this income to travel in a different way to previous generations.

Economic factors have also exerted a decisive influence on overtourism demand. The growing middle class in many countries means that more people can afford to travel. According to McKinsey and WTTC (2017), this is especially significant in countries such as China and India where the expansion of the middle class is incorporating millions of new tourists every year. Improvement in standard of living associated with increased income modifies consumption patterns and attitudes towards work and leisure. There is a reduction in working hours and greater flexibility in the workplace, which leaves more free time for leisure, travel, and personal development. Again, this results in a greater number of shorter trips, which tend towards the concentration of the visitors in the most significant attractions.

Finally, tourism management based on the paradigm of permanent economic growth characteristic of neoliberalism has been largely responsible for the processes analyzed above. This paradigm has led to destination planning strategies to capture more demand in a public-private collaboration framework (García-Hernández et al., 2019). These growth strategies have been associated, in many cases, with selling cities as tourist commodities, thus handing over their control to global supply chains that operate outside communities (Milano et al., 2019). In a sector where market failures are well documented (Buitrago & Caraballo, 2019), this loss of control of public space explains a major part of the aforementioned problems.

As overtourism has worsened, managers of certain destinations have sought to regain control by proposing management alternatives. These alternatives have been clearly insufficient to overcome overtourism, since they are primarily measures at the destination level within the prevailing paradigm and fail to act on the driving forces of overtourism at the global level (see Section 4.1). Overtourism is not just a matter of the number of tourists, but also involves how these tourists are managed (UNWTO, 2018).

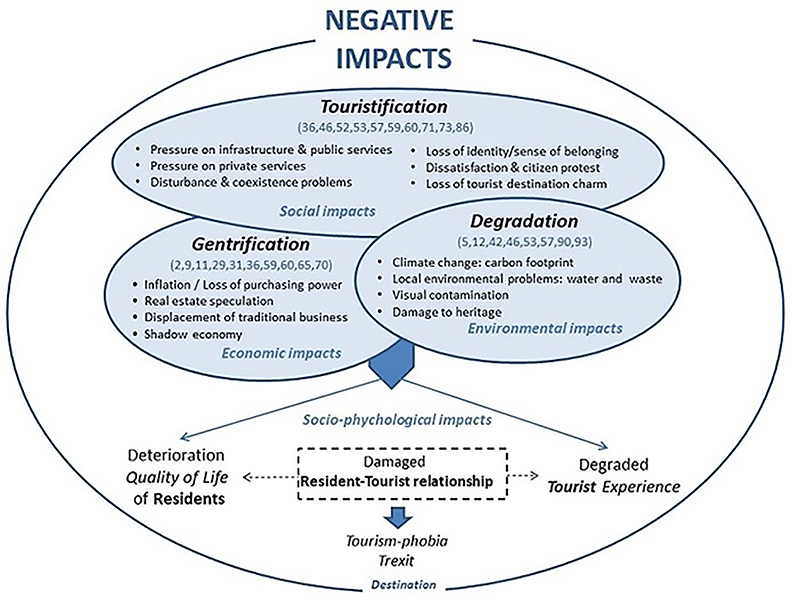

Despite the extensive general scientific literature on the impacts of tourism, there are few studies that analyze the specific impacts of overtourism, and even scarcer are those that do so empirically by providing solid methodologies that demonstrate the causality of such impacts. Most studies we have reviewed focus on the study of negative impacts, which confirms that this is certainly an unsustainable phenomenon to be avoided.

On the other hand, although the reviewed work analyzes economic, environmental and social impacts, overtourism is mainly associated with how residents and tourists perceive these impacts and how these perceptions affect quality of life and satisfaction with the trip. This introduces a new group of sociopsychological impacts into the game, thereby necessitating the use of measurement tools in addition to social indicators to capture the implicit subjective elements. Surveys and interviews with residents, stakeholders and tourists are emphasized, since they enable information to be collected on the perceived impacts, both on the level of irritation and attitudes of residents towards the future of the sector, and on tourist satisfaction.

Based on the literature review carried out, in figure 5 the possible impacts of overtourism are systematized and the references to the studies that have analyzed these impacts are given.

Figure 5. Overtourism Conceptual Framework: Negative Impacts. Literature review. Note: The numbers in parentheses correspond to the code of the reviewed papers that deal with negative impacts of overtourism. See references in Table A1 of the Appendix. Source: Authors´own.

A major part of the resources that the tourist uses and/or consumes is shared with residents at the destinations. The excess of tourists caused by overtourism puts intense pressure on resources that are scarce and, on many occasions, fragile. Pressure is placed on infrastructure, public services, leisure activities, accommodation, commercial activities, and environmental resources. This can result in alterations in economic activity, the way of life, and the identity of destinations.

Overtourism is degrading the environment, both locally and globally. Forms of transport linked to overtourism generate serious impacts on climate change (see the review carried out by Veiga et al. (2018)). Low-cost airlines have led to an increase in the number of short-term trips on long-haul flights with a high carbon footprint (Butler, 2018). Regarding cruises, the degradation of maritime environments must also be added to the carbon footprint (Trancoso, 2018).

Furthermore, overtourism has a significant impact at the local level, mainly due to water consumption and waste generation (Baños et al., 2019). Likewise, excessive tourism situations endanger fragile environments such as historical heritage (Jamieson & Jamieson, 2019; Seraphin et al., 2019) and/or protected areas (Maingi, 2019).

Economic impacts lead to gentrification in several ways. On the one hand, the increases in demand produced by excess tourism place an upward pressure on prices, negatively affecting the purchasing power of the resident (Milano, 2018). This process is especially intense in the real-estate market, where speculative dynamics are frequent. One of the forms of hosting characteristic of overtourism involves the rental activity through P2P platforms. The increase in housing for tourist use reduces the supply of residential housing, resulting in increased house prices for both rental and purchase (Gutiérrez-Tao et al., 2019). As a result, members of the local population are forced to leave the tourist neighbourhoods, thereby promoting tourist gentrification (Panayiotopoulos & Pisano, 2019).

Another problem related to this type of accommodation is that it presents high levels of the shadow economy, which exerts a very negative impact on public income, generates unfair competition against other forms of accommodation, and makes it more difficult for tourism managers to control both its quantity and quality (Goodwin, 2017).

Recent studies point towards an intense relationship between tourist gentrification and commercial gentrification due to the touristification of the city’s historic centre (Peeters et al., 2018). The intensification and concentration of tourism in these areas has led to the substitution of traditional commerce for activities more geared towards tourism, mainly in the form of souvenir and restaurant franchises. These new economic uses imply a loss of identity of the neighbourhood (Gravari-Barbas & Jacquot, 2019) that affects both local inhabitants (by increasing the reasons for their exodus to other areas) and tourists themselves (due to the loss of charm and authenticity of the destination).

Overtourism, by involving a high spatio-temporal concentration, increases the pressure on infrastructures, public services, and leisure activities, which generates overcrowding situations. Furthermore, when overtourism is linked to certain tourist typologies, it exacerbates problems of security and coexistence, vandalism, crime, noise, and solid waste disposal (see Smith et al. (2019) regarding Budapest).

All the aforementioned issues diminish the quality of life of residents (Gutiérrez-Taño et al., 2019) and create negative experiences for tourists (Liu & Ma, 2019). Relations between residents and tourists are undermined, which explains why anti-tourism citizen movements have emerged in destinations like Barcelona: a phenomenon known as ‘anti-tourism’ or “tourismphobia” (Milano et al., 2019; Papathanassis, 2017). When these limits are reached, the process can become irreversible (Cheung & Li, 2019). In this respect, the work of Perkumienė & Pranskūnienė (2019) is highly interesting, in which, based on a review of the literature, the balance between the right to reside and the right to travel is discussed.

As has been pointed out, the very existence of the phenomenon of overtourism constitutes practical evidence of the lack of implementation of the pillars of sustainability, which makes it necessary to take another step to facilitate the effective implementation of a responsible tourism model. In this context, the third pillar of an integrated conceptual framework for the analysis of overtourism must include management alternatives, that is, governance models that enable the transition. In this Section, we include the conclusions of the earlier pandemic literature review regarding the alternatives that have been developed. Then, in Section 5, we present the results and discuss how the changes that are taking place in the sector as a result of the pandemic may represent an opportunity for the transition towards a responsible tourism model.

As the situations of overtourism worsened, the responsible for certain destinations proposed various management alternatives in order to regain control. In Table 1, the contributions of the earlier pandemic literature review carried out on this topic have been systematized. Overtourism management measures have been classified into categories (Regulatory measures, Financial and tax measures, Measures on ICT, Marketing measures and Awareness and sensitization measures), whereby the objective(s) with which they are linked are indicated (Adjust the flow of tourism to the carrying capacities, Promote a new behaviour of tourists and residents, Adapt the tourism sector to environmental aims) and the related papers are referenced.

Table 1. Strategic goals and measures for the management of pre-pandemic overtourism. Literature review.

|

INTEGRAL PLANNING (3,8,20,24,38,47,57,59,60,71,81,90) |

|||

|

MEASURES |

STRATEGIC GOALS |

||

|

Adjust tourism flow (3,59,60,65, 67,71,83,90,91) |

Promote a new behaviour tourists & residents (3,11, 29,31,57,65,73,91,93) |

Adapt tourism to environmental aims (5,8,12,18,46, 57,59,71,83,90,93) |

|

|

1. Regulatory measures (5,8,26,29,31,38,42,46,57,73,91,93) |

— |

— |

— |

|

Limit flights, ships, or passengers disembarking |

X |

— |

X |

|

Limit accommodation in hotels or tourist apartments (e.g., moratorium on new hotel licences, control over licensed and unlicensed accommodation, introduction social licences to operate through sharing-economy platforms). |

X |

— |

X |

|

Review regulations regarding opening times of visitor attractions |

X |

X |

— |

|

Review regulations regarding access for large groups to popular attractions |

X |

X |

— |

|

Limit any unacceptable social behaviour on the part of tourists (e.g., fines for walking around half-naked or for drinking in public spaces) |

— |

X |

— |

|

2. Financial and tax measures (3,11,18,31,57,59,91) |

— |

— |

— |

|

Promote investment in facilities and infrastructure to involve residents (e.g., crowdfunding or matching grants) |

— |

X |

— |

|

Tourist taxes (e.g., “bed tax” on accommodation, “day visitor” tax) |

X |

X |

X |

|

3. ICT measures (3,8,11,18,20,26,42,46,47,59,91,93) |

— |

— |

— |

|

Big data, smart technological solutions, and specific applications |

X |

X |

X |

|

4. Marketing measures (11,18,20,57,60) |

— |

— |

— |

|

Demarketing |

X |

X |

|

|

Tourist selection strategies |

X |

X |

|

|

Promotion of less popular attractions/destinations/itineraries |

X |

X |

X |

|

5. Awareness and sensitization measures (5,24,31,57,59,91,93) |

— |

— |

— |

|

Engaging local communities in tourist activity |

— |

X |

— |

|

Educating tourists regarding the issues of sustainability and overcrowding |

— |

X |

X |

|

Communication campaigns to foster positive coexistence between tourists and residents |

— |

X |

— |

|

Creation of city experiences that benefit both residents and visitors could be advisable |

— |

X |

— |

|

Awareness campaigns to reduce environmental impact (e.g., more sustainable use of water in hotels; or ‘flying shame’ campaign to replace planes with other transports fewer pollutant) |

— |

X |

X |

|

Note: The numbers in parentheses correspond to the code of the reviewed papers that deal with alternative strategies to handle overtourism. See references in Table A1 of the Appendix. |

|||

Hitherto, these alternatives have clearly proven insufficient to overcome overtourism (Butler & Dodds, 2022), since very few proposals act on the driving forces of overtourism at a global level and/or impose changes in the dominant socio-economic paradigm. They mostly comprise destination-level measures focused on alleviating the local consequences of overtourism and remain within the prevailing paradigm.One example of such measures is known as the 5D solutions: Deseasonalization, Decongestion, Decentralization, Diversification and Deluxe tourism. These measures, if implemented in isolation, are only technical solutions that could temporarily alleviate some of the negative impacts of overtourism, but would fail to eradicate them by not addressing their underlying causes (Milano et al., 2019). In fact, staying within the status quo of continued tourism growth and consumption, 5D solutions could even contribute to perpetuating situations of overtourism (Hall, 2019).

The same happens with many of the initiatives carried out in practice in the context of smart cities. Many of them remain mere technical solutions framed in neoliberal ideals. An “intelligent ecosystem” is created that favours the privatization of public services and the interests of global private corporations, thereby generating an increased dependence on technology and a depoliticization of city management (García-Hernández et al., 2019, p.11). The holistic concept of a smart city should be implemented, which would combine the digital revolution and the democratic revolution (Cardullo & Kitchin, 2018), so that smart cities can become a true alternative.

Driven by social movements of resistance to overtourism, the growing literature under development involves the ability to promote a paradigm shift in tourism planning: tourism degrowth (see Milano et al. (2019) for an analysis of the theoretical bases of tourism degrowth and its application to the case of Barcelona). The following questions lie at the centre of this debate: Who benefits from the continued growth of tourism? How are the costs and benefits of overtourism shared? As discussed in Section 3, while the costs of overtourism are borne by the destination communities, a large part of its benefits are absorbed by global chains outside its scope. Therefore, Milano et al. (2019, p. 1870) advocate a change from ‘growth for development’ to ‘degrowth for liveability’.

Although sustainable degrowth (Kallis et al., 2018) could become an alternative to overtourism, conflicting interests regarding tourism and the external forces that dominated pre-pandemic tourism explain the real difficulties for its implementation.

Despite the emergence of the aforementioned approaches to management, the pre-Covid tourism reality continued to be dominated by situations of overtourism (Butler & Dodds, 2022). Although recent awareness of the problems derived from this phenomenon and the apparently broad consensus that responsible tourism must be the model to follow (Burrai et al., 2019; Koščak & O’Rourke, 2021), the problem lay in the implementation of the changes necessary for the transition, in the actors involved, and in the different roles assumed by the public administration. The global geopolitical context and the dynamics of the tourism system itself, conditioned by multiple conflicting interests, explain that breaking the existing inertia and reprogramming the sector when it is running is a practically impossible task (it is not possible to change the engine of a Formula1 car in full race: a pit stop is necessary).

The COVID-19 pandemic paralysed economic activity, with immediate devastating effects on the tourism sector. UNWTO (2021) shows a 74% fall in international arrivals for 2020, which translates into a loss of $ 1,300 million in export revenues from international tourism. Overnight, it went from overtourism to undertourism or zero tourism (Gössling et al., 2021; Kainthola et al., 2021). However, this “halt” in activity could have become an opportunity to reset the situation and, by breaking the inertia indicated, to change the existing paradigm and begin the effective transition towards responsible tourism (Niewiadomski, 2020).

Furthermore, the pandemic has modified individual and collective attitudes and behaviours that are inducing not only relevant changes in society and in the business sector, but also political-institutional transformations (Brouder, 2020). Much of these changes are in line with the characteristics of responsible tourism (Brouder, 2020), which also presents an exciting opportunity to regain control of spaces and societies.

On the demand side, tourists and residents have begun to prefer safer and less crowded environments, slower rhythms of life, close-proximity and nature trips, and the local area is valued with greater involvement with the community, thereby increasing both concern and environmental occupation. Although it is too early to confirm, a change in values is beginning to point towards those of responsible tourism (Lew et al., 2020).

On the supply side, the changes that the pandemic is inducing in the business sector also represent an opportunity to replace the previous model. Certain mainstream business formats are declining and, simultaneously, others are emerging (Chaney & Seraphin, 2021), which invest in practices of a more sustainable nature. We are in a favourable context for innovation in which reforms that the tourism industry still had pending are accelerating, such as the ecological and digital transitions (Nunes & Cooke, 2021).

Finally, the political-institutional transformations derived both from the changes in the international geopolitical situation and from the growing role of public institutions in the management of Covid could become the main spring for the change of model. The international situation experienced temporary deglobalization due to mobility restrictions, which forced each country to demonstrate its mechanisms to the market (Niewiadomski, 2020). Likewise, the role of public institutions in managing the pandemic and its consequences is being decisive: first, in relation to health and safety; second, in the protection of the most affected groups; third, in the reactivation of economic activity; and fourth, in the promotion of models of a more sustainable, responsible, and resilient nature against future shocks (Brouder, 2020). This last point is crucial to ensure an effective transition to responsible tourism. In a context in which bailouts are necessary to reactivate the economy and where social and environmental objectives are more present, conditioning said aid to the effective fulfilment of these objectives can serve as the trigger for change. This is the case of the European Union, which has conditioned its NextGenerationEU rescue plan on the Member States making progress in the ecological and digital transition (European Commission, 2020). All the aforementioned factors could represent a golden opportunity to overhaul overtourism and to lay the foundations for the implementation of a model for responsible tourism.

Even if the pandemic has opened up a favourable scenario for the change of model, it could also carry serious risks. The urgency for a rapid recovery and to compensate for the losses caused during periods of confinement can lead to strategies that revert to focusing on increasing the number of tourists without worrying about the externalities they generate (Hall et al., 2020). This second scenario, defended by a part of the tourism industry and certain governments, could lead to new situations of overtourism: re-overtourism.

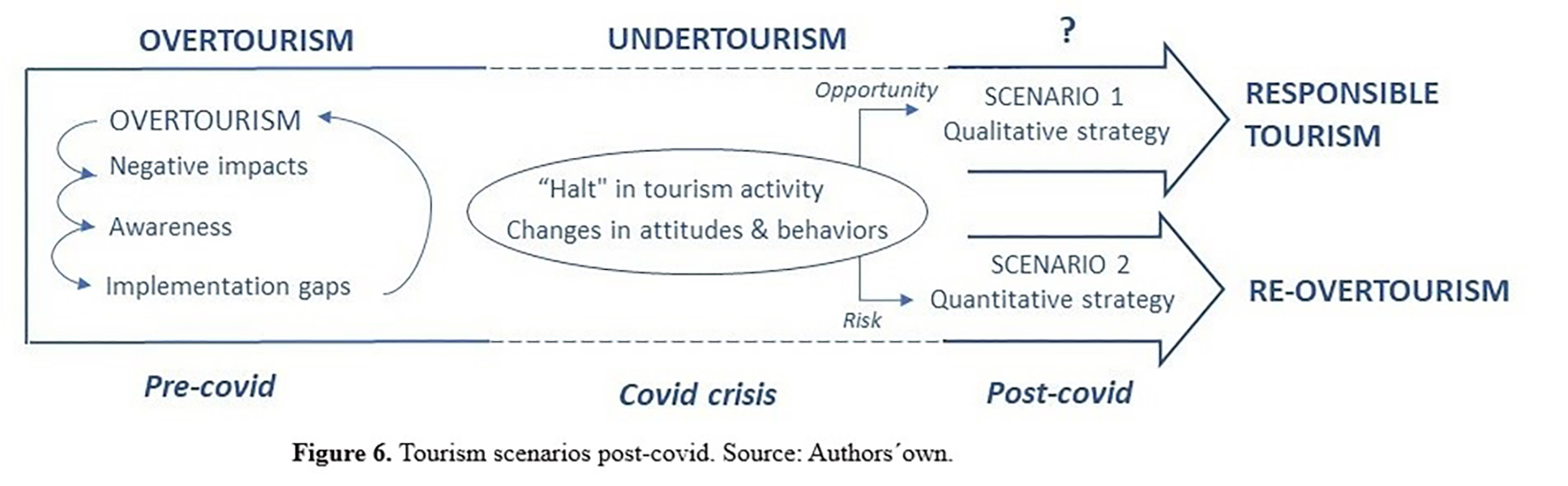

In figure 6, based on the pre-Covid tourism situation and the opportunities that the pandemic has revealed for the change of model, the possible scenarios are summarized.

Figure 6. Tourism scenarios post-covid. Source: Authors´own.

Faced with this situation, the various administrative levels share a common responsibility, but with differentiated roles. The supranational level is appropriate for the assumption of the leading role in the paradigm shift, by establishing the theoretical bases to guide the strategies to be followed and by providing the necessary funding for their implementation. The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations could provide a suitable framework (see Boluk et al., 2019).

The local level has the mission of adapting these strategies to the reality of its territory and society, while working in three perspectives: normative, organizational, and innovative (Fontaniri & Traskevich, 2021; Pasquinelli & Trunfio, 2021). Thus, strategies are characterized by their integral, participative, flexible, smart, and sustainable character. These strategies are integral, in the sense of addressing both the driving forces and causes of overtourism, in order to prevent overtourism and its consequences from mitigating their effects. They are also participative to the extent that the design and implementation of the actions must be based on cooperation and co-management between all stakeholders (public and private, global and local levels). Flexibility involves adapting to each specific situation since there are no one-size-fits-all recipes. Strategies must also be smart to promote changes in tourism governance, taking advantage of the opportunities provided by ITC (Perles-Ribes et al., 2020), but without forgetting the identity and history of the destination, in terms of ambidextrous management (Seraphin et al., 2018). Sustainability is achieved by including approaches that go beyond quantitative growth models of tourism, through the long-term, socially, culturally, and environmentally sustainable development of tourism (Benner, 2019; Higgins-Desbiolles, 2018).

In this work, a literature review on earlier pandemic overtourism has been carried out to contribute towards the development of a systematic and integrated conceptual framework.

This review of the literature has enabled us to characterize the state of research in this area, determine its main limitations, and establish future lines of work. Although the literature on overtourism has grown exponentially in recent years, most research deals with the subject in a very indirect and partial way. The research studies that tackle overtourism as their main topic are mostly exploratory case studies focused on specific cities (mainly European), which carry out partial analyzes of only a certain dimension of the phenomenon. The main limitations found involve the partial focus and the deficiencies in the measurement of the studies. Although overtourism is an eminently quantitative term (it refers to an excessive amount of tourism), most of the work analyzed assumes the existence of overtourism without offering new tools and/or measurement methodologies to corroborate this supposition. Likewise, the causes or consequences of overtourism are addressed theoretically and in isolation, with few empirical studies that provide solid methodologies to demonstrate causality among the factors analyzed. Furthermore, these studies do not focus on the underlying causes or drivers of overtourism.

The debate over whether overtourism is a new phenomenon remains open in the Academy with reputed arguments reported both in favour (Doods & Butler, 2019; Mihalic, 2020; Nilsson, 2020) and against (Capocchi et al. 2020; Wall, 2020). After having reviewed the literature, we are situated on the front line since, although overtourism is rooted in concepts that are highly consolidated in the tourism literature, it also presents relevant new nuances that make it necessary to introduce new analytical approaches, new ways of measuring, and especially new management approaches that avoid repeating the pre-pandemic mistakes (Butler & Dodds, 2022).

We propose a multidisciplinary conceptual framework that systematizes in pictorial form the different dimensions of overtourism, centres on its driving forces, and integrates its causes and consequences by focusing on new nuances that explain the emergence of the phenomenon. In this way, we extend the approach offered by most of the authors who have negotiated with the conceptualization of the phenomenon and who have focused solely on the consequences (Mihalic, 2020; Perkumienė & Pranskūnienė, 2019) or on the causes (Doods & Butler, 2019; Nilsson, 2020). In doing so, we have been able to reveal a major contradiction that may explain the difficulties in overcoming overtourism. Although the driving forces and causes are in the global context, the negative impacts are primarily concentrated in destinations.

According to Mihalic (2020) and Burrai et al. (2019), the analysis framework in which we have developed the conceptual model is that of (ir)-responsible tourism. The existence of situations of overtourism provides empirical evidence of the lack of implementation of the ideas of sustainability. Hence, to overcome overtourism, it is also necessary to consider facilitators of responsibility, understood as the step towards action. Therefore, in addition to integrating causes and consequences into the conceptual framework of overtourism, we have considered the role of tourism governance by analyzing both the management alternatives that have been proposed and the opportunities that may arise from the pandemic for the change of model.

In the pre-Covid stage, the problems derived from overtourism (gentrification, degradation, and touristification) and their damaging impacts on the quality of life of the resident and on the satisfaction of the tourist were unmasked, and revealed the urgent need to promote a change of model; however, it remained impossible to implement. Most of the proposed measures have to date remained within the existing tourism growth paradigm and have not addressed the true driving forces behind overtourism. These measures are at the local level and deal with some of the consequences of overtourism but, by themselves, have insufficient capacity to modify its global underlying causes. The very inertia of the neoliberal economic system and the acceleration in ICT together with the loss of control over destinations explains the difficulties in changing the model. When any machine is at full capacity, it is difficult to repair its engines. The Covid-19 pandemic paralysed tourism activity and has induced changes in society and in the business sector and has triggered political-institutional transformations. All this is presented as a golden opportunity for the transition towards responsible tourism: the real challenge for the new post-Covid era is not when tourism will return, but how it will return.

In this respect, a debate has been opened among academics in which we find sceptical voices regarding the transition (Brouder, 2020; Hall et al., 2020) and other more optimistic researchers with whom we identify (Gössling et al. 2021; Lew et al., 2020). We expect a global adaptation of the sector to new values that facilitate responsible tourism: that destinations adapt to sustainability (green energy, circular economy, safeguarding of heritage, citizen participation, stable employment); that local destinations and markets are rediscovered; that the boom in slow tourism becomes a trend for the future; that security is established as one more characteristic for destinations; that the capacity for resilience becomes the central element of the sector, thereby allowing destinations to remain flexible and to adapt to increasingly changing realities. We have the reasons and the occasion to provide the transition from overtourism to responsible tourism: it is now time to take action. Tourism research has, today more than ever, the mission of signalling the way forward.

This work opens relevant lines of future research. On the one hand, using a similar methodology, it would be possible to deepen the analysis of overtourism in different geographical areas or tourist typologies. On the other hand, it would be interesting to complete this review of the pre-pandemic tourism literature with a review of the post-pandemic literature in order to assess the differences.

The Authors would like to express their appreciation to the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments provided during the revision of the paper.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain’s Government (Ref. PGC2018-095992-B-I00). Also, the research is partially supported by the Research Groups of Research in Applied Economics (SEJ132 and SEJ 258. Plan Andaluz de Investigación, Junta de Andalucía, Spain).

the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in relation to the publication of this article. All authors have been equally involved in all stages of the research as well as in both the drafting of the content and the manuscript revision processes.

Alexis, P. (2017). Over-tourism and anti-tourist sentiment: An exploratory analysis and discussion. “Ovidius” University Annals, Economic Sciences Series, 17(2), 288-293.

Alonso-Almeida, M.D., Borrajo-Millán, F., & Yi, L. (2019). Are social media data pushing overtourism? The case of Barcelona and Chinese tourists. Sustainability, 11(12), 33-56. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123356

Baños, C.J., Hernández, M., Rico, A.M., & Olcina, J. (2019). The Hydrosocial Cycle in Coastal Tourist Destinations in Alicante, Spain: Increasing Resilience to Drought. Sustainability, 11(16), 4494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164494

Benner, M. (2019). From overtourism to sustainability: A research agenda for qualitative tourism development in the Adriatic (Paper No. 92213). MPRA.

Bianchi, R. (2018). The political economy of tourism development: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.08.005

Biddulph, R., & Scheyvens, R. (2018). Introducing inclusive tourism. Tourism Geographies, 20(4), 583-588. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1486880

Boluk, K.A., Cavaliere, C.T., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 847-864. https://doi.org// 10.1080/09669582.2019.1619748

Bourliataux-Lajoinie, S., Dosquet, F., & del Olmo Arriaga, J.L. (2019). The dark side of digital technology to overtourism: the case of Barcelona. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 11(5), 582-593. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-06-2019-0041

Brouder, P. (2020). Reset redux: possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 484-490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760928

Buitrago, E.M., & Caraballo, M.A. (2019). Exploring the links between tourism and quality of institutions. Cuadernos de Turismo, 43, 215–247. https://doi.org/10.6018/turismo.43.09

Buitrago, E.M., & Yñiguez, R. (2021). Measuring Overtourism: A Necessary Tool for Landscape Planning. Land, 10(9), 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10090889

Burrai, E., Buda, D.M., & Stanford, D. (2019). Rethinking the ideology of responsible tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 992–1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1578365

Butler, L. (2018). Challenges and Opportunities. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 10(6), 635-641. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-07-2018-0042

Butler, R. (1974). The social implications of tourist developments. Annals of Tourism Research, 2(2), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(74)90025-5

Butler, R. W., & Dodds, R. (2022). Overcoming overtourism: a review of failure. Tourism Review, 77(1), 35-53. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-04-2021-0215

Capocchi, A., Vallone, C., Amaduzzi, A., & Pierotti, M. (2020). Is ‘overtourism’ a new issue in tourism development or just a new term for an already known phenomenon? Current Issues in Tourism, 23(18), 2235-2239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1638353.

Capocchi, A., Vallone, C., Pierotti, M., & Amaduzzi, A. (2019). Overtourism: A literature review to assess implications and future perspectives. Sustainability, 11(12), 3303. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123303

Cardullo, P., & Kitchin, R. (2018). Smart urbanism and smart citizenship: The neoliberal logic of ‘citizen-focused’ smart cities in Europe. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X18806508

Chaney, D., & Seraphin, H. (2021). Covid-19 crisis as an unexpected opportunity to adopt radical changes to tackle overtourism. Anatolia, 31(3), 510-512. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2020.1857804

Chaudhry, P.E., Cesareo, L., & Pastore, A. (2019). Resolving the jeopardies of consumer demand: Revisiting demarketing concepts. Business Horizons. 62 (5), 663-677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2019.05.002

Cheung, K.S., & Li, L.H. (2019). Understanding visitor–resident relations in overtourism: developing resilience for sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(8). 1197-1216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1606815

Del Chiappa, G., Atzeni, M., & Ghasemi, V. (2018). Community-based collaborative tourism planning in islands: A cluster analysis in the context of Costa Smeralda. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 1(8), 41-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.10.005

Dodds, R., & Butler, R. (2019). The phenomena of overtourism: a review. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(4), 519-528. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-06-2019-0090

European Commission, (November, 2020). EU’s next long-term budget & NextgenerationEU. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/eu-budget/long-term-eu-budget/eu-budget-2021-2027_es#latest (Accessed December 2020).

Fontanari, M., & Traskevich, A. (2021). Consensus and diversity regarding overtourism: the Delphi-study and derived assumptions for the post-COVID-19 time. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 11(2), 161-187. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTP.2021.117375

García-Hernández, M., Ivars-Baidal, J., & Mendoza, S. (2019). Overtourism in urban destinations: the myth of smart solutions. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 83, 2830, 1–38. http://dx.doi.org/10.21138/bage.2830

Ghidouche K.A.Y., & Ghidouche, F. (2019). Community-based ecotourism for preventing overtourism and tourismophobia. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 11(5), 516-531. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-06-2019-0035

González-Pérez, J.M. (2020). The dispute over tourist cities. Tourism gentrification in the historic Centre of Palma (Majorca, Spain). Tourism Geographies, 22(1), 171-191. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1586986

Goodwin, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for tourism. Goodfellow Publishers Limited

Goodwin, H. (2017). The Challenge of Overtourism (Working Paper No. 4, 1-19). Responsible Tourism Partnership.

Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C.M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

Gough, D.A., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2013). Learning from research: systematic reviews for informing policy decisions: a quick guide. Nesta, London.

Gravari-Barbas, M., & Jacquot, S. (2019). Mechanisms, actors and impacts of the touristification of a tourism periphery: the Saint-Ouen flea market, Paris. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(3), 370-391. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-11-2018-0093

Gutiérrez-Taño, D., Garau-Vadell, J.B., & Díaz-Armas, R.J. (2019). The influence of knowledge on residents’ perceptions of the impacts of overtourism in P2P accommodation rental. Sustainability, 11(4), 1043, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041043

Hall, C.M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 27 (7), 1044-1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456

Hall, C.M., Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2020). Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 577-598. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759131

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2018). Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 157-160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.017

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). The “war over tourism”: challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(4), 551-569. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1803334

Inskeep, E. (1991). Tourism planning: An integrated and sustainable development approach. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Jamieson, W., & Jamieson, M. (2019). Overtourism management competencies in Asian urban heritage areas. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(4), 581-597. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-08-2019-0143

Jang, H., & Park, M. (2020). Social media, media and urban transformation in the context of overtourism. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6(1), 233-260. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-08-2019-0145

Kainthola, S., Tiwari, P., & Chowdhary, N. R. (2021). Overtourism to Zero Tourism: Changing Tourists’ Perception of Crowding Post Covid-19. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, 9(2), 115-137. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83909-706-520211002

Kallis, G., Kostakis, V., Lange, S., Muraca, B., Paulson, S., & Schmelzer, M. (2018). Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 43(1), 291–226.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-025941

Koens, K., Postma, A., & Papp, B. (2018). Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability, 10(12), 4384, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124384

Koens, K., Melissen, F., Mayer, I., & Aall, C. (2021). The Smart City Hospitality Framework: Creating a foundation for collaborative reflections on overtourism that support destination design. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management. 19, 100376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.100376

Koščak, M., & O’Rourke, T. (2021). Post-Pandemic Sustainable Tourism Management: The New Reality of Managing Ethical and Responsible Tourism. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003153108

Lew, A.A., Cheer, J.M., Haywood, M., Brouder, P., & Salazar, N.B. (2020). Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation of 2020. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 455-466. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1770326

Liu, A., & Ma, E. (2019). Travel during holidays in China: Crowding’s impacts on tourists’ positive and negative affect and satisfactions. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 41, 60-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.09.008

Maingi, S.W. (2019). Sustainable tourism certification, local governance and management in dealing with overtourism in East Africa. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 11(5), 532-551. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-06-2019-0034

McKinsey & WTTC. (2017). Coping with Success: Managing overcrowding in tourist destinations. World Travel and Tourism Council, London.

Mihalic, T. (2020). Concpetualising overtourism: A sustainability approach. Annals of Tourism Research. 84, 103025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103025

Milano, C. (2018). Overtourism, malestar social y turismofobia. Un debate controvertido. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 16(3), 551-564. https://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2018.16.041

Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J.M. (2019). Overtourism and degrowth: a social movements perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1857-1875. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1650054

Niewiadomski, P. (2020). COVID-19: from temporary deglobalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 651-656. http://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757749

Nilsson, J.H. (2020). Conceptualizing and contextualizing overtourism: the dynamics of accelerating urban tourism. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6(4), 657-671. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-08-2019-0117

Novy, J. (2019). Urban tourism as a bone of contention: four explanatory hypotheses and a caveat. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(1), 63-74. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-01-2018-0011

Nunes, S., & Cooke, P. (2021). New global tourism innovation in a post-coronavirus era. European Planning Studies, 29(1), 1-19, https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1852534

Panayiotopoulos, A., & Pisano, C. (2019). Overtourism dystopias and socialist utopias: Towards an urban armature for Dubrovnik. Tourism Planning and Development. 16 (4), 393-410. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1569123

Papathanassis, A. (2017). Over-tourism and anti-tourist sentiment: An exploratory analysis and discussion. “Ovidius” University Annals, Economic Sciences Series, 17(2), 288-293.

Pasquinelli, C., & Trunfio, M. (2021). The missing link between overtourism and post-pandemic tourism. Framing Twitter debate on the Italian tourism crisis, Journal of Place Management and Development. Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-07-2020-0073

Peeters, P.M., Gössling, S., Klijs, J., Milano, C., Novelli, M., Dijkmans, C.H.S., Eijgelaar, E., Hartman, S., Heslinga, J., Isaac, R., & Mitas. O. (2018). Research for TRAN Committee-Overtourism: impact and possible policy responses. European Parliament, Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies, Transport and Tourism.

Perkumienė, D., & Pranskūnienė, R. (2019). Overtourism: Between the right to travel and residents’ rights. Sustainability, 11(7), 2138, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072138

Perles-Ribes, J. F., Ramón-Rodríguez, A. B., Moreno-Izquierdo, L., & Such-Devesa, M. J. (2020). Machine learning techniques as a tool for predicting overtourism: The case of Spain. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(6), 825-838.https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2383

Pinke-Sziva, I., Smith, M., Olt, G., & Berezvai, Z. (2019). Overtourism and the night-time economy: a case study of Budapest. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-04-2018-0028

Sarantakou, E., & Terkenli, T.S. (2019). Non-institutionalized forms of tourism accommodation and overtourism impacts on the landscape: the case of Santorini, Greece. Tourism Planning and Development, 16(4), 411-433. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1569122

Seraphin, H., Sheeran, P., & Pilato, M. (2018). Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management. 9, 374-376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.01.011

Seraphin, H., Zaman, M., Olver, S., Bourliataux-Lajoinie, S., & Dosquet, F. (2019). Destination branding and overtourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 38(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.11.003

Smith, M.K., Sziva, I.P., & Olt, G. (2019). Overtourism and resident resistance in Budapest. Tourism Planning and Development, 16(4), 376-392. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1595705

Trancoso, A. (2018). Venice: the problem of overtourism and the impact of cruises. Journal of Regional Research. 42, 35-51. https://www.redalyc.org/jatsRepo/289/28966251003/28966251003.pdf

UNWTO (2013). Demographic change and tourism. European Tourism Commission and UNWTO, Madrid.

UNWTO (2018). ‘Overtourism’? understanding and managing urban tourism growth beyond perceptions. UNWTO, Madrid.

UNWTO (2021). Covid-19 y el sector turístico. UNWTO. Available at: https://www.unwto.org/es/covid-19-y-sector-turistico-2020 (Accessed December 2020).

Veiga, C., Santos, M.C., Aguas, P., & Santos, J.A.C. (2018). Sustainability as a key driver to address challenges. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 10(6), 662-673. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-08-2018-0054

Wall, G. (2020). From carrying capacity to overtourism: a perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 212-215. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-08-2019-0356

Table A1. Selected papers codes

|

2 |

(Alexis, 2017) |

52 |

(Liu & Ma, 2019) |

|

3 |

(Alonso-Almeida et al., 2019) |

53 |

(Maingi, 2019) |

|

5 |

(Baños et al., 2019) |

57 |

(McKinsey & WTTC, 2017) |

|

8 |

(Benner, 2019) |

59 |

(Milano, 2018) |

|

9 |

(Biddulph & Scheyvens, 2018) |

60 |

(Milano et al., 2019) |

|

11 |

(Bourliataux-Lajoinie et al., 2019) |

65 |

(Novy, 2019) |

|

12 |

(Butler, 2018) |

67 |

(Panayiotopoulos & Pisano, 2019) |

|

18 |

(Chaudhry et al., 2019) |

68 |

(Papathanassis, 2017) |

|

20 |

(Cheung & Li,2019) |

70 |

(Peeters et al., 2018) |

|

24 |

(Del Chiappa et al.,. 2018) |

71 |

(Perkumienė & Pranskuniene, 2019) |

|

26 |

(Dodds & Butler, 2019) |

73 |

(Pinke-Sziva et al., 2019) |

|

29 |

(Ghidouche & Ghidouche, 2019) |

79 |

(Sarantakou & Terkenli, 2019) |

|

31 |

(Goodwin, 2017) |

81 |

(Seraphin et al.,2018) |

|

36 |

(Gutiérrez-Taño et al., 2019) |

83 |

(Seraphin et al., 2019) |

|

38 |

(Higgins-Desbiolles, 2018) |

86 |

(Smith et al., 2019) |

|

42 |

(Jamieson & Jamieson, 2019) |

90 |

(Trancoso, 2018) |

|

46 |

(Koens et al., 2018) |

91 |

(UNWTO, 2018) |

|

47 |

(Koens et al., 2021) |

93 |

(Veiga et al.,2018) |

|

Note: The complete list of the 99 papers reviewed can be found in the Supplementary Material. |

|||