DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/rea.2021.i41.03

Formato de cita / Citation: Foronda-Robles, C. et al. (2021). The role of the web and social media in the tourism promotion of a world heritage site. The case of the Alcazar of Seville (Spain). Revista de Estudios Andaluces, 41, 47-64. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/rea.2021.i41.03

Correspondencia autor: foronda@us.es (Concepción Foronda-Robles)

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Concepción Foronda-Robles

foronda@us.es  0000-0002-3632-2410

0000-0002-3632-2410

Department of Human Geography, University of Seville. Maria de Padilla s/n. 41004 Seville (Spain).

Caterina Mondelli

mondelli.caterina@yahoo.it  0000-0003-0623-0651

0000-0003-0623-0651

Post-graduate scholarship, Decree Rep. No. 171/2018 - Prot. 1494 of 18/10/2018, at the Department of Humanities and Social Science, University of Sassari (Italy).

Donatella Carboni

carbonid@uniss.it  0000-0002-1050-3344

0000-0002-1050-3344

Department of Humanities and Social Science, University of Sassari, Via Roma 151. Sassari (Italy).

INFO ARTÍCULO

Received: 30-08-2020

Revised: 25-11-2020

Accepted: 05-12-2020

ABSTRACT

The information and communication technologies have revolutionized tourism and the promotion of cultural attractions. They constitute a tool with which to enhance the cultural heritage and economy of a territory in the context of tourism innovation.

The article aims to analyze the potential of the website and social media of the Alcazar of Seville—declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO—in promoting tourism. The quality of this official website and social media was analyzed and evaluated through the 7 Loci model and the Nvivo tool, with weaknesses and strengths being identified. The analysis highlighted weaknesses in areas such as the content, which needs to be optimized, the impossibility of viewing the information in other languages, and the global management of the website and social media, which should be reviewed. The study also presents strengths, including excellent visibility and good positioning in the main search engines, links from the website to social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube) and the adequacy of the time needed to download the pages.

KEYWORDS

Cultural promotion

Alcazar of Seville

Tourism

Web

Social media

RESUMEN

Las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación han revolucionado el turismo y la promoción de atractivos culturales. Estas son herramienta para potenciar el patrimonio cultural y la economía del territorio a partir de la innovación turística.

El artículo tiene como objetivo analizar el potencial de la web oficial y las redes sociales del Alcázar de Sevilla en la promoción turística, Patrimonio Mundial de la UNESCO. La calidad del sitio oficial y sus redes sociales fue analizada y evaluada a través del modelo 7 Loci y la herramienta Nvivo, identificando sus debilidades y fortalezas. El análisis destacó entre las debilidades, el contenido a optimizar, la imposibilidad de visualizar la información en otros idiomas y una gestión global para revisar. El estudio presenta fortalezas como excelente visibilidad y buen posicionamiento en los principales buscadores, enlaces a redes sociales (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram y Youtube) y que los tiempos para descargar las páginas son los adecuados.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Promoción cultural

Alcázar de Sevilla

Turismo

Web

Redes sociales

The advent of digitalization has led to a profound upheaval in the structure of the tourism industry. The Internet, and in particular the Web, allows tourists to find information, to book, to access products and services, and compare tourism offers in an independent way, and thus put together a holiday (Hayles, 2012; Rossi, 2005).

The new technologies allow tourists to express themselves: through Web 1.0 the dissatisfied tourist could only express discontent through confidential questionnaires or pre-established modules, whereas today (from Web 2.0 to Web 4.0) it can be done publicly, with reviews and comments being shared on specialized websites or hotel reservation portals, for example. Web 2.0 is based on three pillars: interaction, sharing and participation.

The proliferation of new digital tools and social media, including PDAs and smartphones, provides online interconnectivity and the ability to offer specific new content, with the limitations (of time and space) of the traditional channel-based services being exceeded (Noti, 2013; Parra-López et al., 2012).

Web 3.0 is characterized by the greater awareness, and consequent greater control, of users with regard to content, and the evolution of graphics from 2D to 3D (Mistilis & Buhalis, 2012). Web 3.0 is a “semantic web”, in which sharing is not only a sharing of information and syntax but a continuous sharing of meanings, of semantics (Kourouthanassis et al., 2015; Tavakoli & Wijesinghe, 2019; Villa, 2015).

The advent of new technological factors is leading the network to the next evolutionary stage: Web 4.0 (Gustafsson, 2019). These factors are:

The new technologies have revolutionized tourism, and nowadays any destination that wants to be competitive must continually update itself according to the wishes of the visitor. Moreover, tourists now look for applications that can enhance the traditional ways of visiting cultural tourism attractions and often have a desire to intensify the travel experience with interactive content (Battelli et al., 2017; Yousaf et al., 2020).

Social media constitute one of the communication channels most used by the general public, which is why cultural heritage companies have assigned more funding to these new Internet advertising technologies. In the current market, the use of social media, blogs and image galleries allows the companies that manage historic monuments to get to their potential customers faster and in real time (Handley 2012; Vila & Vila, 2012). The benefits of having a personalised company website are obvious: the possibility of being connected directly to and obtaining information on or from the customer; reducing costs by eliminating intermediaries; and offering the buyer the convenience of purchasing the product or service directly from the comfort of home or a mobile device. Thanks to the Internet, it is both easier and cheaper to update information, adapt to different situations and change strategy according to changing circumstances (Peukert, 2019). Through social media, for example, users exchange information and opinions on products or monuments and museums. A company reading the various comments on social media or platforms like TripAdvisor can easily understand what does or does not meet the needs and desires of the tourist and so take steps to improve its image (Massarotto, 2011; Van der Zee et al., 2020).

It is evident that a new concept of tourism promotion now exists. Today, heritage organizations assign most of their promotional budget to online channels and less to traditional guides or media. Tourist service operators must face up to the increasingly stiff and global competition and more than ever take into account the satisfaction of the customer, who now has access to a wide selection of tools with which to look for the best offer (Battelli et al., 2017; Cozzi, 2010).

The tourism and cultural attraction sector is hugely influenced by the Web and the new information and communication technologies. The new technologies make it possible to find solutions to problems related to the restoration or conservation and use of cultural heritage, as well helping to improve the management of cultural heritage and enabling the generation of economic development based on innovation (López et al., 2010; Ortega & Labella, 2018; Padilla-Meléndez & del Águila-Obra, 2013; Pallud & Straub, 2014). Therefore, the new technologies play a considerable role in this sector: they are an instrument for the promotion and enhancement of the cultural heritage and the economy of a territory. The contribution of the new technologies to the cultural sector provides an opportunity to preserve, project and spread an area’s cultural heritage more quickly and effectively than with traditional tools; any tourism attraction that intends to be competitive must constantly update itself with new technologies, and this is especially true of cultural tourism, which is a sector that relies on offering and receiving a great deal of information (Garau, 2017; Verdiani, 2011).

The new technologies facilitate the sharing of cultural content, and so the application of multimedia and new technologies to the cultural heritage sector is a necessary condition to guarantee the development of cultural heritage without geographical boundaries. There are several technological solutions commonly adopted in the cultural heritage sector, among the most productive being audio guides, touch screens, interactive paths, virtual visits on portable devices, direct experiments and interactive installations. Thus, the new technologies have undoubtedly led to a greater quality of communication and an increased number of ways to visit a cultural attraction, and are applied in conjunction with the traditional tools still in use, such as explanatory panels and group guides (Bertacchini & Morando, 2013; Charitonos et al., 2012).

The cultural tourist has gone from being a consumer of information to a generator of information on social media, in blogs, and so on, and actively collaborates by offering opinions on tourist destinations (Conti & Moriconi, 2012). The new cultural tourist is able to independently evaluate and analyze what is offered, without pressure from the tourism company, and prefers to consult the reviews and opinions of strangers, as they are in all certainty independent and therefore more reliable than a travel agency or tour operator (Ejarque, 2015).

The new technologies improve the tourist experience and guarantee a return on investment for the tourist destination, having become key tools for the promotion of cultural heritage and establishing the profile of the visitor, at the same time as being very useful for the achievement of excellence in the cultural tourism destinations themselves (Caro et al., 2014; Tom Dieck & Jung, 2017). The international as well as the national tourist is increasingly attracted to culture and thanks to the new technologies can now learn more than previously about the cultural heritage of a territory. Technology used consciously to improve the visitors’ experience of a destination can become an important element of differentiation from the competition.

The presence on the Internet of heritage organizations in the tourism sector and of associated entities has become increasingly important, because of which it is now necessary to invest first and foremost in a website, taking into account and evaluating all those aspects that determine its quality. There are several issues to consider when building a website capable of satisfying the needs of both the site owner and the end user, including the obligation to offer complete, adequate and reliable information, and the provision of all those functions necessary to guarantee for the user ease of access to and navigability within the site.

As the Covid-19 pandemic spreads, millions of people in quarantine have sought out travel and cultural experiences in their homes. The culture was indispensable during this period, and the demand for virtual access to museums, heritage sites, theatres and performances reached unprecedented levels, despite the closure of more than 80% of UNESCO World Heritage properties. Sanitary confinement has demonstrated the importance of new technologies and means in daily life. For this reason, more and more digital solutions are being developed to create virtual tourism experiences.

The aim of this study is to analyze the promotional strategy developed on the official website and on social media by the Alcazar of Seville. To this end, two specific aspects have been considered. First of all, the interventions and activities offered by the Alcazar are analyzed using the 7 Loci model. Secondly, the messages generated on social media are analyzed through a content cloud using Nvivo 11 software.

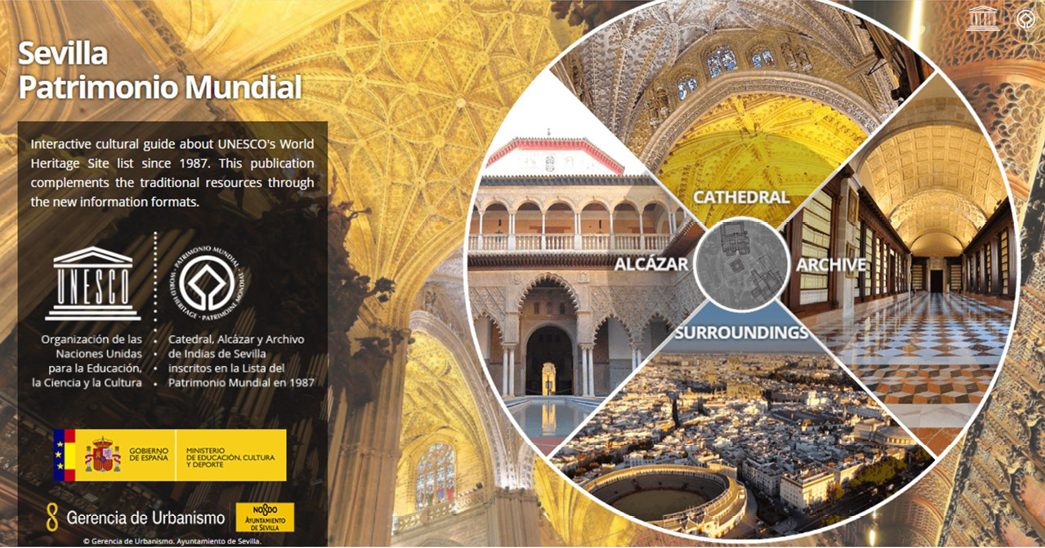

In the city of Seville (Spain), there is a UNESCO World Heritage Site (WHS)—so declared in 1987—consisting of the Cathedral, the Alcazar and the Archivo de Indias (Figure 1). These three buildings form a remarkable monumental complex in the heart of Seville, incorporating vestiges of Islamic culture, centuries of ecclesiastical power, royal sovereignty and the trading power that Spain acquired through its colonies in the New World.

Figure 1. Map of the UNESCO World Heritage Protection Zone, consisting of Cathedral, Alcazar and Archivo de Indias, Seville (Spain). Source: UNESCO (2010).

The three buildings enjoy the highest degree of protection that exists in heritage legislation, at both a regional and a national level, since they have been declared Properties of Cultural Interest in the Monuments category.

The Alcazar of Seville sits on the southern edge of the historic city. The Alcazar is one of the oldest royal residences still in use in Europe. It is a military and palatial complex that consists of different palaces, urban defences and gardens (Tabales, 2010).

The Alcazar comprises a group of buildings of approximately 14,000 m² and gardens that occupy an area of 70,000 m². It presents some specific features: it groups architectural ensembles and gardens from different artistic periods; it is considered the first civic building in Seville; and it faces the challenge of configuring a model of sustainable management and compatibility between public visits and events, tourism and the conservation of cultural heritage (Mínguez, 2012).

The Alcazar is a place of interest for tourists, and manages to strike a balance between publicity and tourist visits and conservation, research and management. The World Heritage of Seville is an example of how cultural heritage is experiencing a remarkable change in dynamics as an engine of economic, social and tourism development (Fernández-Baca & Rodríguez, 2009).

The Alcazar is accessible, with information boards throughout and an audio guide service for visitors. At the same time, complementary activities such as guided tours, temporary exhibitions and concerts are offered within the complex. Due to the beauty of its buildings and gardens, the Alcazar has been a source of inspiration for artists and thinkers over the centuries. In the 19th century it attracted numerous Romantic travellers and from the 20th century on it has become the setting for legendary films.

The number of visits to the Alcazar has increased considerably, the inclusion of this monument in the WHS register certainly having had a significant promotional effect, and continues to grow, in part due to the dissemination of its heritage within the context of World Heritage Sites, but also due to the celebration of events and its use as a setting for TV series, the latter having made an important contribution to this increase. The number of visitors has risen from 1,085,647 in 2008 to 2,067,016 in 2019—190% over 11 years— (Figure 2). The Alcazar visitor profile is 24.5% groups and 75.5% individual visitors, with 40% being Spanish and 60% foreign (Troitiño et al., 2020).

Figure 2. Visitors to the Alcazar from 2008 to 2019. Source: Seville Tourism Website, 2020.

The COVID-19 crisis has left the city empty of tourists. Even so, the Alcazar has remained open, apart from during the period of confinement from March to June. The number of tourist visits has been well below that of other years, due to the reduced capacity imposed by the COVID-19 health and safety regulations: from January to August 2020, the Alcazar received 351,422 visitors (Seville Tourism Website, 2020).

In order to verify the effectiveness of the official website of the Alcazar of Seville as a tool for tourism and cultural promotion, we used the 7 Loci model (2QCV2-3Q). The 7 Loci model is so called because it incorporates the seven loci communes that Cicero introduces in his treatise “Rhetoricorum, seu De inventione rhetorica”, in which he expresses the principles of a good orison (prayer). In the model in question, the seven loci identify seven different elements that comprise a website and which must be taken into consideration when evaluating the quality of the site as a whole.

So that both the strengths and the weaknesses of the official website of the Alcazar—http://www.alcazarsevilla.org/—could be identified and understood, a decision was made to apply the 7 Loci model, as this model facilitates the identification of certain elements, the opportunely combined evaluation of which may lead to suggestions as to how the quality of a website may be improved. Moreover, the application of the 7 Loci model is relatively simple and does not require specific IT skills (Signore, 2005). There are several models available for website evaluation but we chose to work with the 7 Loci model as it is particularly adaptable to the tourism sector and allows the classification of all the features present on existing web sites, even on those that are very innovative. Among the most well known models for assessing the quality of a website, apart from the 7 Loci model, the following should be mentioned: the sectorial indices (Censis-Rur, 2002), Website Quality Features (Yang et al., 2005), Quality Principles for Cultural Websites (Mavromoustakos & Andreou, 2007; Rio & Brito, 2010), A Quality Model for Websites (Polillo, 2005) and Evaluating Web Pages (Biscoglio, 2007; Karkin & Janssen, 2014). The 7 Loci model can be used for different purposes: to compare sites, to deepen the evaluation of a site, to discover the strengths and weaknesses of a site, and so on (Kumar et al., 2017).

The tool used was the NVivo 11 content analysis software for tourism and cultural promotion, and the work was carried out with the Ncapture plugin, which was installed in the Chrome browser. Interesting information was obtained on the publications of the Alcazar of Seville and the actions presented in its strategy. The research began in November 2017 and ended in June 2020.

The contents under study are text and multimedia files—image, video and audio files, for example—taken from the official website (https://www.alcazarsevilla.org/), Facebook (https://es-es.facebook.com/RealAlcazarSevilla/), Twitter (https://twitter.com/sevillaalcazar), Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/realalcazarvilla/) and YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC24bMHEFlmUNAgS7AaYHSjg).

The authors analyzed 324 news posts from the Alcazar website, 1,867 Facebook posts, 5,049 Tweets, 216 Instagram posts and three YouTube videos. The data for 2019 are looked at in more detail those for the other years, and are grouped into the following categories: gardens, palace rooms, events and others.

The promotion of the Alcazar of Seville has changed over the decades and consists of three stages. First, in the 1980s and 1990s, the opening days and hours of the monument were published in the form of announcements in magazines and newspapers. There were also full- or double-page spread ads to promote exhibitions and other cultural activities within the Alcazar complex. Second, since 2000 there has been an expansion in the promotion of the site, which began specifically in May 2000 when the annual magazine “Annotations from the Alcazar of Seville” was first published, this being both a scientific and cultural magazine and a promotional tool. Third, the Alcazar makes itself available for forums and programmes of an academic, cultural and educational character aimed at both promoting this cultural heritage site as a meeting and training space and increasing its presence on social media.

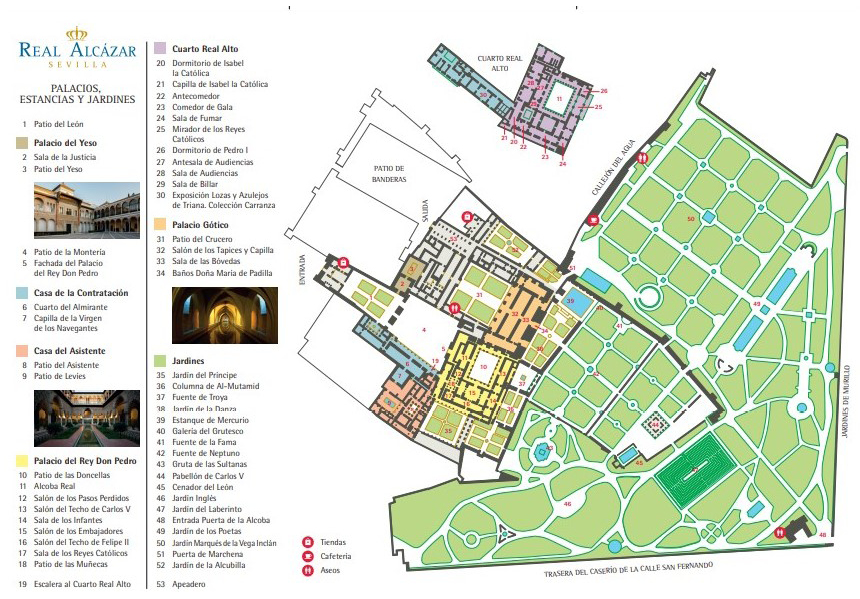

The tour of the Alcazar follows no official itinerary. However, the Alcazar does offer a free map with 53 points of interest (Figure 3) and the opportunity to pay for the audio guide, which is available in eight different languages at a price of 5 euros; alternatively, a guided tour can be taken with one of the external guide organizations that can be found outside the monument.

Figure 3. Map of the Alcazar offered to visitors. Source: Alcazar de Sevilla (2020).

The Alcazar is a much visited cultural monument, so it is essential that its official website be efficient and well structured so that tourists who are visiting for the first time can find as quickly and easily as possible the desired information and services related to ticket booking and opening days and hours in order to avoid long queues, for example. The main results that emerged from the application of the 7 Loci model show a positive identity for the website in question, content to be optimized, considerable problems related to ticket booking services, excellent location and visibility, management issues to be reviewed, especially as regards site maintenance, insufficient use, and feasibility appropriate to the type of website (Table 1).

Table 1. Application of the 7 Loci model to the Alcazar website.

|

7 Loci Model |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

QVIS |

Logo recognizable and clearly visible. |

No trademark related to the Seville or Andalusia brand. |

|

Direct links to social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube channel). |

Lack of UNESCO World Heritage Site logo. |

|

|

Graphic appearance maintains consistency with the brand. |

— |

|

|

QVID |

General information on its cultural heritage, history, events, exhibitions, activities for children, and so on. |

No reference links to regional or municipal bodies. |

|

CVR |

Online ticket booking service. |

Booking services are not always guaranteed and queues at the monument are a problem. |

|

VBI |

Intuitive URL. |

— |

|

Excellent visibility and good positioning on the main national and international search engines. |

— |

|

|

Possibility of contacting the institution. |

— |

|

|

QVANDO |

— |

Slow information updates. |

|

— |

Proper operation of the site during maintenance and updating is not guaranteed. |

|

|

QVOMODO |

Graphic design for viewing the site from a smartphone and/or tablet. |

Available languages: Spanish, English and French (the latter only in the “Tickets” section). |

|

Clear menus, easy navigability, and site map. |

— |

|

|

QUIBUS AUXILIIS? |

Intuitive terms and symbols. |

— |

|

Time required to download the appropriate pages. |

— |

Source: Own elaboration.

Through the 7 Loci model, the main characteristics of the website have been identified, which could be used in the future for making improvements to and ensuring better use of the website.

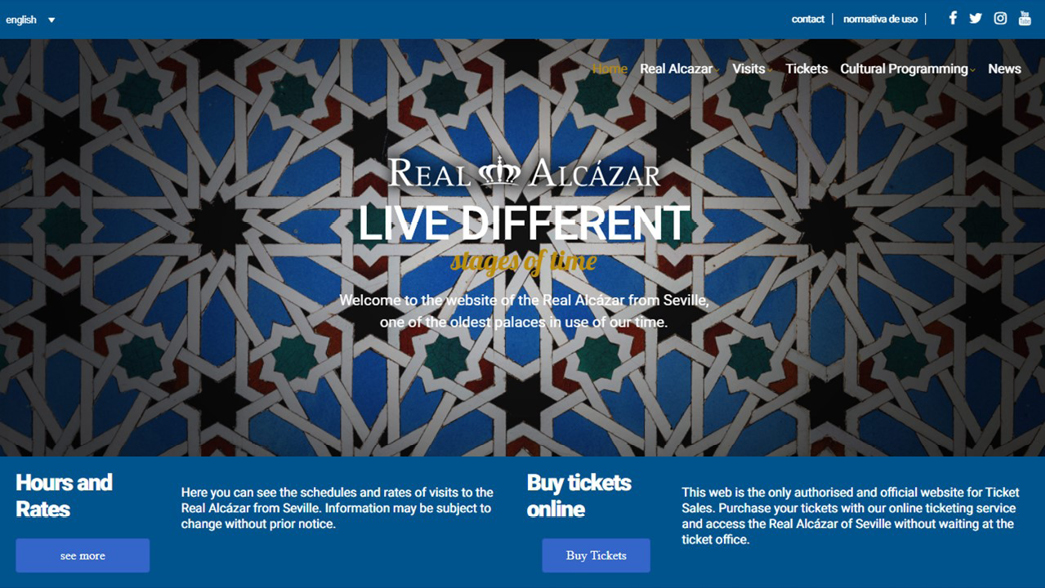

The first dimension of the 7 Loci model, which is the identity of the website, identifies a recognizable and clearly visible logo—communicating the identity of the website—placed in the upper central part of each page. In the top right-hand corner of the homepage are located the logos of the various social media that act as links to the official pages managed by the Royal Alcazar Board of Patronage: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Alcazar official website homepage. Source. Alcazar de Sevilla (2020).

The Alcazar’s promotion strategy is constantly expanding, from the most traditional techniques of monument promotion to promotion on the Web and the most advanced technologies, such as virtual reality or Seville World Heritage (Figure 5), a Web and mobile app providing information about the Cathedral, Alcazar and Archivo de Indias monumental complex, the latter service being increasingly demanded by the digital tourist (Mascort-Albea et al., 2016).

Figure 5. Seville World Heritage app homepage. Source: Ayuntamiento de Sevilla (2016).

On the official Alcazar website, there are several tools that offer visibility and cultural dissemination. Among these tools, some are official, such as the social media—Facebook, Twitter and Instagram—and others are unofficial, such as TripAdvisor. However, they all offer, albeit in different ways, visibility of the asset (Table 2). Table 3 displays the types of content found on social media.

Table 2. Dissemination of content on the Alcazar of Seville. 2011–June 2020.

|

Information |

Start date |

Visits |

Publications |

|

Web news |

March 2012 |

— |

324 news posts |

|

|

January 2013 |

259,788 visits |

1,867 news posts, 818 photos and 33 videos |

|

|

December 2011 |

6,249 followers |

5,049 Tweets |

|

|

April 2017 |

7,362 followers |

216 publications |

|

YouTube |

January 2019 |

94 subscribers |

3 videos |

|

TripAdvisor |

May 2011 |

34,445 opinions |

— |

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 3. Types of content on the Alcazar of Seville’s social media. 2019.

|

Contents |

Web news |

|

|

|

|

Gardens |

— |

17.5% |

30% |

31% |

|

Palace rooms |

— |

30.5% |

44% |

53% |

|

Events |

100% |

52.0% |

26% |

10% |

|

Others |

— |

— |

— |

6% |

Source: Own elaboration.

Since 2012, the news website has focused on providing information on the celebration of events and only publishes an average of 40 publications a year.

The Alcazar’s Facebook page has been more prolific, with 1,867 news items, 818 photos and 33 videos having been posted in the years of activity. It has posted an average of 250 news items a year, with the highest number in 2014 and 2015. The photographs are mostly related to the events that take place throughout the year (52%), followed by images of the palace rooms (30.5%) and the gardens (17.5%).

The strength of Twitter lies in its ability to communicate quickly with large groups at a very low cost. Twitter is a privileged channel on which Tweets inform about, comment on or recommend both travel to the Alcazar to visit events and in general its wealth of heritage. Twitter is an ideal tool for promoting tourism, with shared messages influencing travel choices, in particular those concerning monuments, destinations and itineraries, for those on vacation. @SevillaAlcazar has 5,049 Tweets and 6,249 followers. Of all the Tweets, 70% are Retweets from @NochesAlcazar, @Sevillaciudad, @sevillaalDia, @SevillaTourism, @Ayto-Sevilla, @labienal, @andalucianet, @IAPHpatrimonio and @AndaluciaDestinoDeCine, so the Alcazar itself has only published 30%. On this social media platform, 50% of the publications are photos (44% palace rooms, 30% gardens and 26% events).

When analyzing the most-frequent-content cloud in the Twitter profile (Figure 6), the gardens and courtyard, and the dramatized night visit, along with the numerous events (concerts, conferences, exhibitions and activities for children), stand out. On the second level are the palace and the wealth of heritage. These topics that the Royal Alcazar Board of Patronage focuses on involve its followers and establish a relationship with them through tools such as Retweets and simple comments, where visitors can express their appreciation of the cultural asset in question, and news posts related to historical and/or cultural issues. Therefore, based on the fact that most of the Tweets are related to the field of tourism and cultural promotion, it can be deduced that there is a common communication strategy.

Figure 6. Word cloud from @SevillaAlcazar’s Twitter account. Source: Own elaboration.

The Alcazar’s Instagram account currently contains 306 posts, and from April 2017 to December 2019, 216 were published. Of the total number of posts, 31% are related to the natural heritage of the Alcazar to be found in in the surrounding gardens, 53% to the different rooms of the monumental complex, and 10% to events. On the Instagram platform, the posts are divided into four blocks: Corners of the Alcazar, Exhibitions, Visitors’ photos and Gardens of the Alcazar.

Many people upload photographs tagged #realalcazar or #realalcazardesevilla to their Instagram account. The average number of photos associated with this heritage published per day is around seven, which constitutes a significant degree of dissemination.

On TripAdvisor, 34,445 opinions of the Alcazar have been published, of which 95.7% are excellent or very good, and 4.3% are negative. The reasons for the negative opinions include ticket problems, long queues, the treatment by staff and/or tour guides, and limited information in a foreign language. The majority of the opinions are written in English (38.9%), Spanish (20.6%), French (15.2%) and Italian (13.2%).

Another source of tourist promotion, usually coming under the heading of distinctive events, is the shooting of films and television series at the Alcazar, which was previously ignored as a way to attract visitors. Numerous films and series have been shot in the complex since the beginning of the 20th century (Table 4).

Table 4. Films and TV series shot at the Alcazar of Seville.

|

Films |

TV series |

|

La vida de Cristóbal Colón (1916) |

Réquiem por Granada (1991) |

|

Jalisco canta en Sevilla (1948) |

Game of Thrones (2015–2016) |

|

¿Dónde vas, Alfonso XII? (1958) |

Emerald City (2015) |

|

La femme et le pantin (1959) |

La Peste (2017) |

|

Lawrence of Arabia (1962) |

— |

|

La folie des grandeurs (1971) |

— |

|

The Wind and the Lion (1975) |

— |

|

1492: The Conquest of Paradise (1992) |

— |

|

Carmen (2002) |

— |

|

El caballero Don Quijote (2002) |

— |

|

The Kingdom of Heaven (2005) |

— |

|

Alatriste (2006) |

— |

|

Appelsinpiken (2009) |

— |

|

Ispansi (2010) |

— |

|

Knight and Day (2010) |

— |

Source: Own elaboration.

Films and series shot at the Alcazar have boosted promotion, and the most prominent series thus far has been Game of Thrones, with the kingdom of Dorne being recreated in the complex. These cinematographic scenes lead to an increase in the number of visits to the Alcazar and are mentioned in comments on social media:

“Fabulous tour my young adult children were engaged the entire time and loved the fact that Game of Thrones was filmed there”.

The website as a whole has a simple, intuitive and engaging graphic interface, the high quality sliding images that represent the Alcazar being one of the elements that most clearly reflect these qualities. Another important element is that the tones of the site reflect the brand (blue and brown).

It should, however, be considered that the site is not attributable to an institutional tourism promotion body with the ability to strengthen its reliability (Seville, Andalusia or UNESCO). The content of the site is accurate and the main menu, through which you can access the various drop-down menus—Real Alcazar, Visits, Tickets, Cultural Programming and News—remains unchanged on all the pages.

The homepage highlights the upcoming events and the latest news, partly through the abovementioned sliding images, and contains links to the other pages for tickets without waiting, rules of use, schedules and rates, and online booking for free visits on Mondays, for example. Other important pages are those devoted to the Alcazar gardens and the 360º virtual tour.

On accessing the Alcazar website, it can be seen how the infoticketing system articulates the online ticket options: General tour, Monday free admission, Dramatized night visit, and Free entry and free guided tour for those born or residing in Seville. The website services have not been fully effective in guaranteeing the reliability of transactions carried out through the website. There have been some awkward episodes with online booking, such as when several online entrance tickets were sold for a day that the Alcazar was closed and so the buyers had to be refunded, and when the website did not allow tickets to be purchased in advance. Moreover, the services are not guaranteed to always function correctly and those who book a ticket online often have to queue up anyway. Five services (Table 5) are available on the website, taken from the Regulatory Public Price Ordinance for visits and the provision of services in the Alcazar of Seville (December 2017).

Table 5. Services for visitors to the Alcazar of Seville.

|

Services |

Description |

|

Day |

General admission to the ground floor. Admission to visit the Royal Room. Reduced entry for senior citizens and students from 17 to 25 years old. |

|

Night |

Nocturnal visits outside normal opening hours (congresses, conventions or similar). Dramatized night visit (only in Spanish). |

|

Filming of movies and documentaries |

|

|

Unofficial events |

|

|

Visits to exhibitions/events |

|

Source: Own elaboration based on Alcazar de Sevilla (2020).

The Alcazar is in the ongoing process of changing the online booking system so as to continue making progress in the organization of access to the palace complex and avoid the illegal resale of tickets. In 2019, 60.33% of visitors booked online, using a system that allows the user to choose the time of access, online bookings that year representing an increase of 1,343% compared to 2015. The Alcazar is implementing an online named ticketing procedure—using a system that has already been successfully tested at other Spanish monuments, including the Alhambra in Granada—in order to reduce queues at the gates: every half an hour, 300 of these tickets are available online and 75 at the ticket desk.

The increase in the number of visits in recent years is undoubtedly linked to the growth of tourism in the city, but also to the promotion strategies implemented by the city council (Ayuntamiento de Sevilla), which has programmed numerous cultural, educational and social activities within the Alcazar complex, among the most successful being the following: “The Royal Alcazar, your neighbourhood”; “The Royal Alcazar, your winter palace”; “The Royal Alcazar, your summer palace”; concerts such as those in the Nights in the Gardens of the Royal Alcazar series; and dramatized night visits. In addition, there are the numerous and varied cultural programmes and events for children conceived by the Royal Alcazar Board of Patronage to expand the knowledge of the palace complex in the Sevillian population. The year 2019 should be highlighted, when 880 events were held, of which 94.8% were cultural, including concerts, plays, guided tours, activities developed in summer and over the Christmas period, art exhibitions, photographic exhibitions, book presentations and conferences. All these events were advertised on the website, in magazines and on social media.

Finding the website is not difficult: the URL of the site is easy to remember because it includes the name of the cultural asset: http://www.alcazarsevilla.org/. In addition, the site is easily found through the different search engines, and writing “Alcazar” in the search bar of the most used, such as Google, Bing and Yahoo, will place the site in first position. The phone numbers, e-mail address and postal address of the Royal Alcazar Board of Patronage are provided so that it can be contacted in case of complaints or requests for information.

The feasibility dimension includes an assessment of how the human, financial and temporal resources available are employed in actions related to the correct functioning of the website, such as ensuring that the terms and symbols used are intuitive and the download times for the pages are adequate. The website analyzed is not a particularly dynamic tool for the promotion of the UNESCO World Heritage Site in question, first and foremost, because it does not seem to have been thought of or built for tourists.

With the confinement brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, the website has been modernized with the “Get to know the Royal Alcazar from home” function, where the 360º virtual tour application runs through 15 rooms using Flash technology, which is a little outdated since it cannot normally be seen in a number of browsers. The previously available but now more frequently accessed Garden Atlas digital platform (https://alcazar.nomadgarden.org/) allows users not only to view the botanical inventory but to visualize its impact and quantify the absorption of CO2 (216,628 kg), with the Alcazar gardens being divided into 31 spaces, these falling within the Islamic, Renaissance, modern and interior garden sections.

With the decline of Facebook, Instagram and Twitter have gained greater importance and experienced significant growth in 2017, in that year positioning themselves as the social media that together generated the highest number of interactions. In social media publications, persuasive communication stands out and details the architectural and landscape attributes of the Alcazar.

Prosumers (people who both consume and produce a particular commodity) connected on social media share their experiences and insights. This situation has spawned a new approach that is different to conventional marketing strategies. The new technologies that have been incorporated into official web pages and social media are being used to promote cultural tourism (Nguyen et al., 2017). Social media are being used by monuments (Widrich, 2018), art galleries and museums (Bautista, 2014; Garibaldi, 2015), festival activities (Llopis-Amorós et al., 2019) and tourist destinations (Huertas & Marine-Roig, 2015). A possible downside is posited by those authors who suggest that social media and the new electronic communication channels could be accelerators of the process of overcrowding destinations (Milano, 2018).

The analysis of the Alcazar of Seville shows how the positioning of its website and links to social media is one of its strengths. However, there are also some weaknesses. For example, the Alcazar should make more use of both the UNESCO brand as a World Heritage Site and the Seville logo on the website and social media. Also, it is essential that this tourist attraction improve the online ticket booking service to avoid inconvenience to customers, optimize the website for viewing from smartphones and tablets, and translate all the website and social media content into other foreign languages (English, French, German and Italian). Another pending issue is the application of the load capacity studies of the palace complex, carried out by Troitiño et al. (2020) to help achieve sustainability for the Alcazar and face the challenges presented by an innovative tourism management model.

Social media have changed the experience of visiting a tourist attraction and how institutions relate to their visitors, by allowing these visitors to identify the content they need to communicate and receive, and the best way to do so. The present article highlights the persuasive communication used by the Alcazar and that this mainly details its architectural and landscape attributes. The amount of social big data available from visitors to cultural heritage websites establishes the importance of studying smart tourism applications and services in order to understand user contexts and thus aid decision making, the creation of marketing strategies and more personalized offers, transparency and trust in dialogue with clients and stakeholders, and the emergence of new business models (Del Vecchio et al., 2018).

There are many limitations when working with public opinion through social media but it is a method that is here to stay, with an increasing amount of research being carried out using social big data. The present study does not offer a complete mapping of the the Alcazar’s use of social media, focusing on a specific time period and the main topics of interest therein.

The digital world is constantly evolving and the future is in semantic tourism websites oriented towards artificial intelligence that can organize content by concept and capable of creating virtual spaces where users can interact (Ryu, 2017; Shi et al., 2016).

With the advent of the COVID-19 health crisis, social media have expanded with very positive effects, because since the enforced closure of cultural buildings there has been greater online openness. Cultural initiatives have not ceased, but rather there has been a sharp increase in online cultural initiatives, and this avenue has led to an acceleration in digital transformation processes. Cultural heritage websites and social media now have to offer virtual tours, as well as setting quizzes or running virtually assisted treasure hunts. The evidence of this online activity has stimulated new reflections on the future direction of approaches to digital culture and how it is used (Agostino et al., 2020).

Cultural institutions must manage their communication with prosumers, promoting interactivity, offering an appropriate response and ultimately disseminating their heritage. Culture, tourism and technologies come together for the management of cultural heritage in a smart economy (Katsoni et al., 2017; Koramaz, 2018). Cultural tourism services can develop smart tourism interactions for visitors by collecting and analyzing geo-tagged multimedia data from available social media (Nguyen et al., 2017), as well as augmented reality and holographic displays (Dieck & Jung, 2017), gamification and other smart interface options (Ioannides et al., 2017).

This work was supported by the National Programme of Fundamental Research Projects within the project “Territorial Intelligence versus Tourist Growth. The planning and management of destinations before the new real estate expansion cycle” (Ref. PGC2018-095992-B-I00), financed by the Spanish Government Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities.

All authors undertake to disclose any existing or potential conflict of interest in relation to the publication of our article.

Contribution:

Agostino, D., Arnaboldi, M., & Lampis, A. (2020). Italian state museums during the COVID-19 crisis: from onsite closure to online openness, Museum Management and Curatorship, 35 (4), 362-372. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2020.1790029

Alcázar de Sevilla (2020, 25 de octubre). Alcázar de Sevilla. https://www.alcazarsevilla.org/

Ayuntamiento de Sevilla (2016, 15 de julio). App Sevilla Patrimonio Mundial. https://sig.urbanismosevilla.org/sevilla_patrimonio_mundial/?lang=en

Battelli, E., Cortese, B., Gemma, A., & Massaro, A. (2017). Patrimonio culturale: profili giuridici e tecniche di tutela. Roma: Roma Tre Press. Edited Book.

Bautista, S. S. (2014). Museums in the digital age: changing meanings of place, community, and culture. AltaMira Press.

Bertacchini E. & Morando F. (2013). The Future of Museums in the Digital Age: New Models of Access and Use of Digital Collections, International Journal of Arts Management, 15(2), 60-72.

Biscoglio, I. (2007). Quality Model for Websites: Theories and Criteria of Evaluation. University of California.

Caro, J. L., Luque, A., & Zayas, B. (2014). Aplicaciones tecnológicas para la promoción de los recursos turísticos culturales. XVI Congreso Nacional de Tecnologías de la Información Geográfica, 938-946. http://hdl.handle.net/10045/46827

Censis-Rur (2002). Le città digitali, Rapporto 2001, Milano, Franco Angeli.

Charitonos K.; Blake C.; Scanlon, E.& Jones, A. (2012). Museum learning via social and mobile technologies: (How) can online interactions enhance the visitor experience? British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 802-819. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01360.x

Chung, N., Han, H., & Joun, Y. (2015). Tourists’ intention to visit a destination: The role of augmented reality (AR) application for a heritage site. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 588-599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.068

Conti, E., & Moriconi, S. (2012). Le esperienze turistico-culturali: creare valore per i turisti culturali e gli stakeholders e valorizzare il patrimonio culturale della destinazione turistica. Il caso Marcheholiday. Mercati e competitività, 4, 73-98. https://doi.org/10.3280/MC2012-004006

Cozzi, P. (2010). Turismo & Web. Marketing e comunicazione tra mondo reale e virtuale, Milano. Franco Angeli.

Cumo, F., Garcia, D. A., Stefanini, V., & Tiberi, M. (2015). Technologies and strategies to design sustainable tourist accommodations in areas of high environmental value not connected to the electricity grid. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 10(1), 20-28. https://doi.org/10.2495/SDP-V10-N1-20-28

Del Vecchio, P., Mele, G., Ndou, V., & Secundo, G. (2018). Creating value from social big data: Implications for smart tourism destinations. Information Processing & Management, 54(5), 847-860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2017.10.006

Dieck, M. C.T., & Jung, T. H. (2017). Value of augmented reality at cultural heritage sites: A stakeholder approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(2), 110-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.03.002

Ejarque, J. (2015). Social Media Marketing per il turismo: Come costruire il marketing 2.0 e gestire la reputazione della destinazione. Hoepli Editore.

Fagioli, M. C. (2015). Human Smarties: The Human Communities of the Future. Computational Science and Its Applications (ICCSA), 2015 15th International Conference, 57-61. http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/ICCSA.2015.14

Fernández-Baca, R. & Rodríguez, M.C. (2009). Patrimonio Mundial en Sevilla: Catedral, Alcázar y Archivo de Indias. Revista del Patrimonio Mundial, 53, 10-16.

Galvagno, P. (2019, January 25). Web 4.0: quali differenze? https://www.posizionamento-seo.com/search-engine-marketing/web-4-0

Garau, C. (2017). Emerging technologies and cultural tourism: Opportunities for a cultural urban tourism research agenda. Tourism in the City (pp. 67-80). Springer, Cham.

Garau, C., & Ilardi, E. (2014). The “Non-Places” meet the “Places:” Virtual tours on smartphones for the enhancement of cultural heritage. Journal of Urban Technology, 21(1), 79-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2014.884384

Garibaldi, R. (2015). The use of Web 2.0 tools by Italian contemporary art museums. Museum Management and Curatorship, 230-243. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2015.1043329

Gustafsson, C. (2019). Conservation 3.0–Cultural Heritage as a driver for regional growth. SCIRES-IT-SCIentific RESearch and Information Technology, 9(1), 21-32.

Handley, A. (2012). Content Marketing: Fare business con i contenuti per il web-Video, Blog, Podcast, Ebook e Webinar di successo. Hoepli Editore.

Hayles, N. K. (2012). How we think: Transforming power and digital technologies. Understanding digital humanities, 42-66. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230371934_3

Huertas, A., & Marine-Roig, E. (2015). Destination brand communication through the social media: What contents trigger most reactions of users? Information and communication technologies in tourism (pp. 295-308). Springer, Cham.

Ioannides, M., Magnenat-Thalmann, N., & Papagiannakis, G. (Eds.). (2017). Mixed reality and gamification for cultural heritage (Vol. 2). Springer.

Jung, T.H., Lee, H., Chung, N. & Tom Dieck, M.C. (2018). Cross-cultural differences in adopting mobile augmented reality at cultural heritage tourism sites, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30 (3), 1621-1645. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2017-0084

Karkin, N., & Janssen, M. (2014). Evaluating websites from a public value perspective: A review of Turkish local government websites. International Journal of Information Management, 34(3), 351-363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2013.11.004

Katsoni, V., Upadhya, A., & Stratigea, A. (2017). Tourism, Culture and Heritage in a Smart Economy. Springer International Publishing.

Koramaz, T. K. (2018). 12 Information and communication technologies in cultural heritage management. Cultural Heritage, 155- 166.

Kourouthanassis, P., Boletsis, C., Bardaki, C., & Chasanidou, D. (2015). Tourists responses to mobile augmented reality travel guides: The role of emotions on adoption behavior. Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 18, 71-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmcj.2014.08.009

Kumar, N., Dadhich, R., & Shastri, A. (2017). MAQM: a generic object-oriented framework to build quality models for Web-based applications. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 8(2), 716-729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-016-0512-5

Llopis-Amorós, M. P., Gil-Saura, I., Ruiz-Molina, M. E., & Fuentes-Blasco, M. (2019). Social media communications and festival brand equity: Millennials vs Centennials. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 40, 134-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.08.002

Lopez, M.; Margapoti, I.; Maragliano, R. & Bove, R. (2010). The presence of Web 2.0 tools on museum website: a comparative study between England, France, Spain, Italy, and the USA, Museum Management and Curatorship, 25(2), 238-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647771003737356

Mascort-Albea, E. J., Ruiz-Jaramillo, J., López Larrínaga, F., & Peña Bernal, A. D. L. (2016). Sevilla, Patrimonio Mundial: guía cultural interactiva para dispositivos móviles. PH, (90), 152-168.

Massarotto, M. (2011). Social Network: costruire e comunicare identità in Rete. Apogeo Editore.

Mavromoustakos, S. & Andreou, A.S. (2007). WAQE: a Web Application Quality Evaluation Model, International Journal of Web Engineering and Technology, 3 (1), 96-120. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWET.2007.011529

Mich, L., Franch, M., & Gaio, L. (2003). Evaluating and Designing the Quality of Web Sites. IEEE Multimedia, 1(10), 34-43. https://doi.org/10.1109/MMUL.2003.1167920

Milano, C. (2018). Overtourism, social unrest and tourismphobia. A controversial debate. PASOS, 16, 551–564.

Mínguez, C. (2012). The management of cultural resources in the creation of Spanish tourist destinations. European Journal of Geography, 3(1), 68-82.

Mistilis, N., & Buhalis, D. (2012). Challenges and potential of the Semantic Web for tourism. e-Review of Tourism Research (eRTR), 10(2), 51-55.

Nguyen, T. T., Camacho, D., & Jung, J. E. (2017). Identifying and ranking cultural heritage resources on geotagged social media for smart cultural tourism services. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 21(2), 267-279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-016-0992-y

Noti, E. (2013). Web 2.0 and the its influence in the tourism sector. European Scientific Journal, ESJ, 9(20), 115-123.

Ortega, G., & Labella, A. (2018). El uso de dispositivos para la interpretación de los bienes culturales en Andalucía. International Journal of scientific management and tourism, 4(1), 589-630.

Padilla-Meléndez, A., & del Águila-Obra, A. R. (2013). Web and social media usage by museums: Online value creation. International Journal of Information Management, 33(5), 892-898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2013.07.004

Pallud J.& Straub D.W. (2014). Effective website design for experience-influenced environments: the case of high culture museums, Information Management, 51, 359-373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.02.010

Parra-López, E., Gutiérrez-Taño, D., Diaz-Armas, R. J., & Bulchand-Gidumal, J. (2012). Travellers 2.0: Motivation, opportunity and ability to use social media. Social media in travel, tourism and hospitality: Theory, practice and cases, 171-187.

Peukert, C. (2019). The next wave of digital technological change and the cultural industries. Journal of Cultural Economics, 43(2), 189-210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-018-9336-2

Polillo, R. (2005). Un modello di qualità per i siti web. Mondo digitale, 4(2), 32-44.

Rio, A., & Brito, F. (2010). Websites Quality: Does It Depend on the Application Domain? Quality of Information and Communications Technology, 493-498. https://doi.org/10.1109/QUATIC.2010.86

Rossi, C. (2005). Le imprese dell’intermediazione turistica di fronte alla sfida del digitale. Risposte strategiche e condotte operative. Napoli: Liguori.

Ryu, K. H. (2017). Research on Semantic Web-Based Custom Travel Model. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 12(20), 9794-9798.

Seville Tourism Website (2020, November 13) Anual Report https://www.visitasevilla.es/en/professionals/research-statistics

Shi, M., Zhu, W., Yang, H., & Li, C. (2016). Applying semantic web and big data techniques to construct a balance model referring to stakeholders of tourism intangible cultural heritage. International Journal of Computer Applications in Technology, 54(3), 192-200. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJCAT.2016.079873

Signore, O. (2005). A comprehensive model for web sites quality. Web Site Evolution (WSE 2005). 30-36. https://doi.org/10.1109/WSE.2005.1

Tabales, M. Á. (2010). La transformación del Alcázar de Sevilla y sus implicaciones urbanas. Archeologia dell´Architettura XIV, 117-130.

Tavakoli, R., & Wijesinghe, S. N. (2019). The evolution of the web and netnography in tourism: A systematic review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 48-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.10.008

Tom Dieck, M. C., & Jung, T. H. (2017). Value of augmented reality at cultural heritage sites: A stakeholder approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(2), 110-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.03.002

Troitiño, MA; Troitiño, L.; Salmeron, P. & Pérez, RM (2020). La visita pública del Real Alcazar de Sevilla. Bases para la reordenación funcional del conjunto monumental. Apuntes del Real Alcázar 20, 126-169.

UNESCO (2020, 25 October). UNESCO World Heritage Cathedral, Alcazar and Archivo de Indias in Seville (Spain). https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/383/

Van der Zee, E., Bertocchi, D., & Vanneste, D. (2020). Distribution of tourists within urban heritage destinations: A hot spot/cold spot analysis of TripAdvisor data as support for destination management. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(2), 175-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1491955

Verdiani, G. (2011). Il ritorno all’immagine, nuove procedure image based per il Cultural Heritage. Lulu. com.

Vila, T. D., & Vila, N. A. (2012). El fenómeno 2.0 en el sector turístico. El caso de Madrid 2.0. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 10(3), 225-238. https://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2012.10.031

Villa, D. (2015). Crowdsourced Heritage Tourism Open-Data, Small-Data and e-Participatory Practices as Innovative Tools in Alps Cultural Heritage Topic: Information Technology and e-Tourism. Cultural Tourism in a Digital Era (pp. 229-230). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15859-4_19

Widrich, M. (2018). Moving Monuments in the Age of Social Media. Future Anterior, 15(2), 132-144.

Yang, Z., Cai, S., Zhou, Z., & Zhou, N. (2005). Development and validation of an instrument to measure user perceived service quality of information presenting web portals. Information & Management, 42(4), 575-589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2004.03.001

Yousaf, A., Amin, I., Jaziri, D. and Mishra, A. (2020). Effect of message orientation/vividness on consumer engagement for travel brands on social networking sites. Journal of Product & Brand Management, Ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2546