Feasibility of Managing Traditional Knowledge

from the Cultureon the Territory

Catherine Sylvia Rosas-Bustos

crosas@unap.cl  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3999-3463

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3999-3463

Facultad de Ingeniería y Arquitectura. Universidad Arturo Prat (UNAP), Chile.

Universidad Arturo Prat, Iquique. Código Postal: 1110939.

María José Vázquez-Cueto y Francisco Gutiérrez-López

KEYWORDS

Traditional Knowledge

Management

Heritage

Rural Communities

Indigenous Communities

Today Latin America faces a constant flow of migration from rural to urban areas. According to ECLAC, Argentina, Brazil and Chile’s rate of urbanization is higher than 80% followed by Costa Rica and Mexico with 60% and 70%. Bolivia and Guatemala present lower rates.

This scenario is a challenge in the global context. According to Goya, Vrsalovic and Sainz, (2010), the rural economic system present both connection and disconnection, which exposes the culture of the rural and indigenous communities to regular harm as their worth as producers and consumers loses value in the global economic system.

OBJECTIVES

The aforementioned, as a consequence, has led to the loss of heritage, demonstrating the urgency to seek management strategies of traditional knowledge (which from now on I will refer to as T.K.) in order to safeguard rural and indigenous heritage as a primary resource for their development.

The management strategies presented in this article seek to foster the sustainable development in rural communities, taking into consideration the systemic evaluation of the viability of each T.K, their acceptability and convenience. It aims for their recovery and valuing on the local and regional level within a specific local network of exchange. After all, Varela’s proposal evaluates the existence of resources, the willingness and will of the groups or communities (2001).

METHODOLOGY

In order to achieve this process, an instrumental definition of T.K. must be established, allowing for the calculation of its operational value. De la Cruz (2005) cited by Bolvito, Macario and Sandoval (2008) «makes a classification of the types of TK presented below: theoretical knowledge…practical knowledge… process knowledge…». (p. 121)

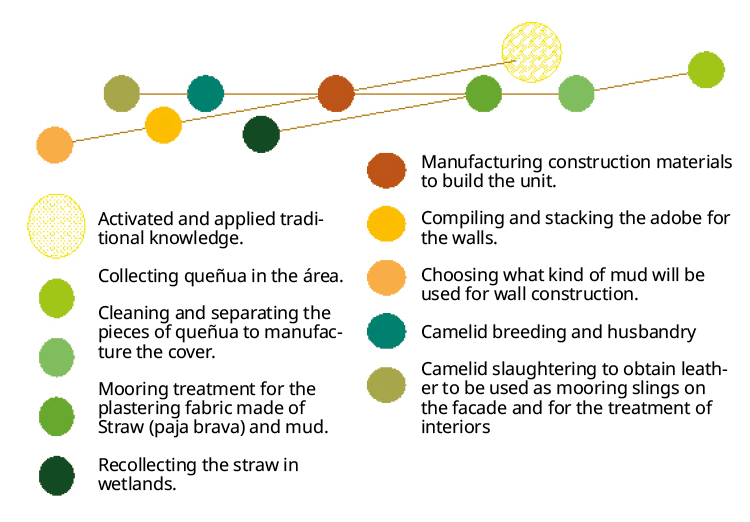

This definition is effective in terms of the practical evaluation of T.K. management, since it takes shape within the spheres of the “being” of the community, the “doing” in its action on its territory, plus the “know-how”, “El ser, el hacer y el saber cómo hacerlo.” This implies accessing new venues to knowledge as we know it, as an addition to the old form of knowledge. This new venue takes into account the process of development and updates. Considering the territorialization or local realization in the production cycle (figure 1) as a system in terms of management or this local territorialization as a discipline.

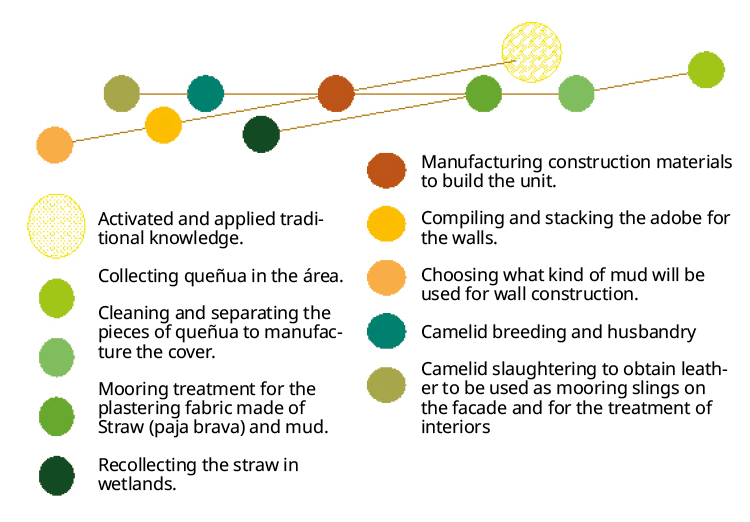

In order for this systemic phenomenon to allow us to demonstrate the feasibility of managing T.K., we must first define the activities that make up the territorial use and occupation program (figure 2) that includes the activities that constitute “doing”, which are pertinent to the T.K.

Figure 1. Productive cycle of traditional knowledge. Source: Author.

These activities in themselves make up a habitable unit, which in itself is a space-time. They are connected with other activities through another space-time, generating a territorial chain, which determines its expression as heritage, purely centered on the application, production and development of mutual collaboration with their environment.

Figure 2. Environmental scope of knowledge. System that correlates to local activities within territorial units pertaining to traditional knowledge. Source: Rosas-Bustos, 2014, p. 61).

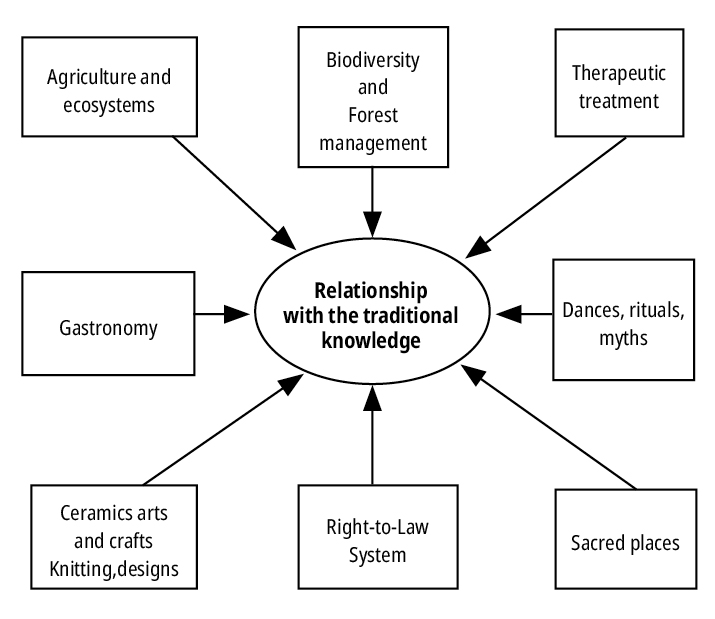

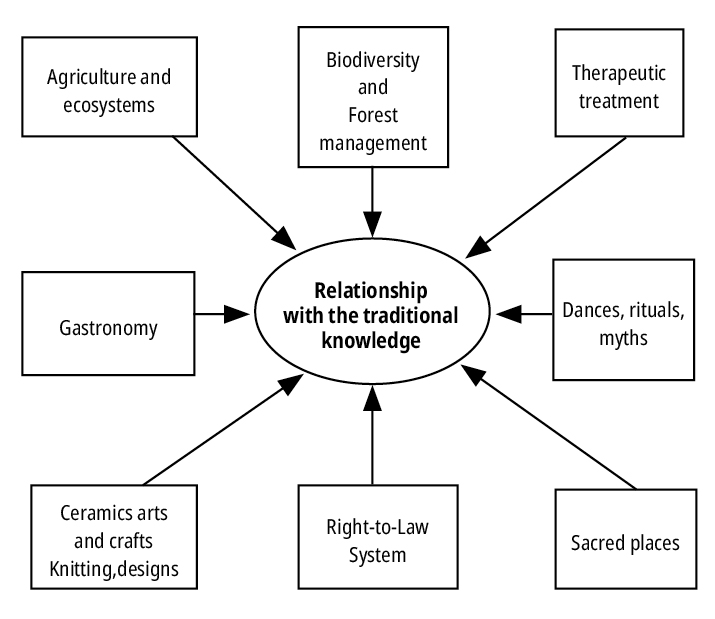

This unit connects with other units, forming relationships between the T.K. The grouping of these units encompass all the cultural expressions of a particular community (figure 3)

Figure 3. Relationships between traditional knowledge. (Traslation) Source: Bolvito, Macario & Sandoval, 2008, p.121)

This is how the environmental and territorial scope of knowledge (figure 2) adds to the totality of the connection of the T.K., which proposes that the internal cultural management within a particular community defines the exchange and interconnection between the T.K. (figure 4).

Figure 4. Exchange and sustainance amongst expressions of traditional knowledge. Source: Rosas-Bustos, 2014, p.63.

MAIN RESULTS

In order to quickly verify the models, which refer to the systemic unit of the T.K., including the territorial scope and the interrelation that is formed within this knowledge, two case studies will be considered. The first case is the “Construction System of mud and straw houses, in the small Andean town of Colchane, the northern area of the Tarapacá region of Chile.” Located in the Andean highland territory, where the Aymara indigenous community lives. In addition, I will introduce a second case, the Handcraft Women in the Tapatío River Basin in the Talca region, in the Southern area of Chile.

In the case of the traditional knowledge applied by the Aymara, their cultural practices stem from the scope of the territory, with the aim of being able to build houses. The general system includes a stone masonry base that sits on adobe and/or stone walls. The roof is made up of a mix of dirt in cloth, mixed with wild straw, supported by a structure of queñuas tied with intestines and camelid leather (Rosas-Bustos, 2014, p. 340).

Image 1. TERRITORY UNIT-LOCAL COMMUNITY. Setting, Isluga province, Town of Colchane.In this ceremonial town there are still some houses with thatched grass roofs and mud walled units made of dirt and stone. Source: Author.

|

Image 2. APPLIED KNOWLEDGE. Facade built by Thatch-mudded cloth. Stone-walled house. Source: Author.

|

Image 3. ONE STEP IN THE BUILDING PROCESS. After the adobe is formed out of mud and aglutinated thatch, the blocks are piled up and set to dry. Source: Author.

|

Image 4. PRESENT LOCAL CONTEXT. Sacred town of Isluga, town of Colchane. New and old housing. Source: Author.

This diagram includes the T.K. environmental and territorial scope. It is implemented as a building technique for Aymara housing, where each action was developed by the Isluga community, aimed at building a traditional house encompassing the following framework (figure 5).

Figure 5. General systems that list the local activities pertaining to the traditional knowledge. This process pertains to the Aymara houses adobe, stone building system located in Isluga. Source: Rosas-Bustos, 2014, p. 66.

This masonry technique is slowly vanishing. The knowledge linked to the execution of mud and straw roofing was replaced by zinc and aluminum sheets, attached to wood or metal frames brought from the city. Sometimes these walls are reinforced with rocks to withstand the strong winds in the area.

This analysis reveals that this traditional knowledge is no longer working on its territorial scope. This suggests that if the value given to this T.K. is not restored, the patrimonial value or the patrimonialization process will not support its productive cycle. This may result in unsustainable activities in the community. This knowledge’s intrinsic value cannot be traded in higher exchange system. The Aymara traditional architectural patrimony may be at risk.

Image 5. Adobe units covered by sheets of zinc nailed to the roof structure and reinforced by rocks.

Source: Author.

Image 6. Handcraft fruit jam. Source: Author.

Image 7. Mapuche vertical woven textile. Source: Author.

Image 8. Handcrafted sea shells. Source: Author.

Image 9. Organic agriculture. Source: Author.

Image 10. Organic agriculture by the sea. Source: Author.

In order to prevent this from happening, reaching out to the comunity to verify willingness to generate potential value for these practices is needed. Developing ways to reintroduce these cultural practices in order to reactivate the development of this T.K. is a viable option. This needs to be discussed with and verified by the community. Assessing their willingness to engage in such activity is valuable.

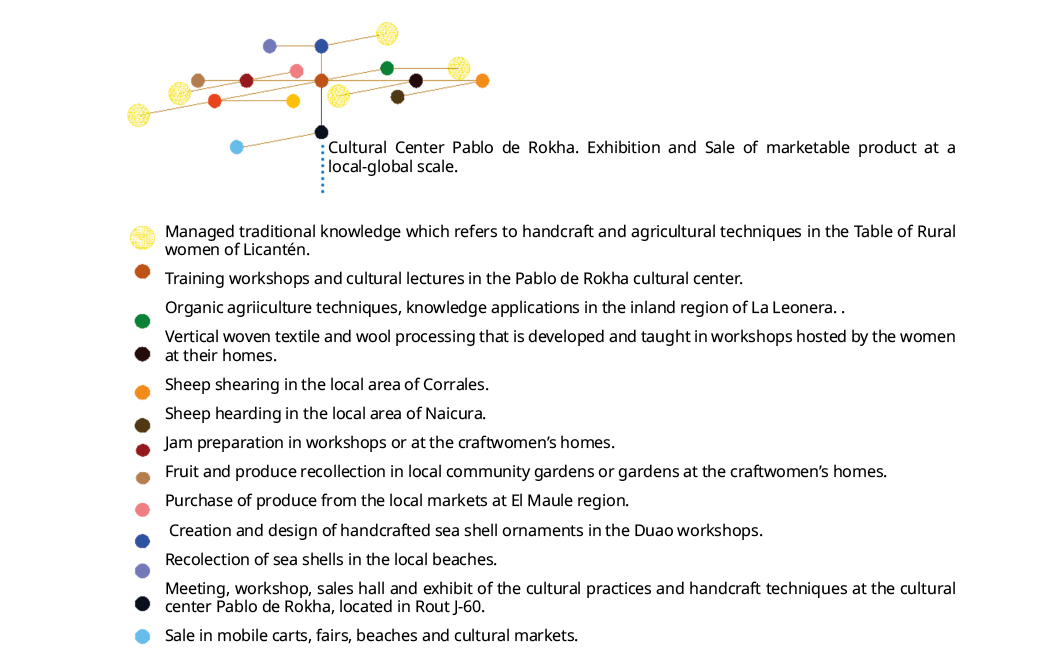

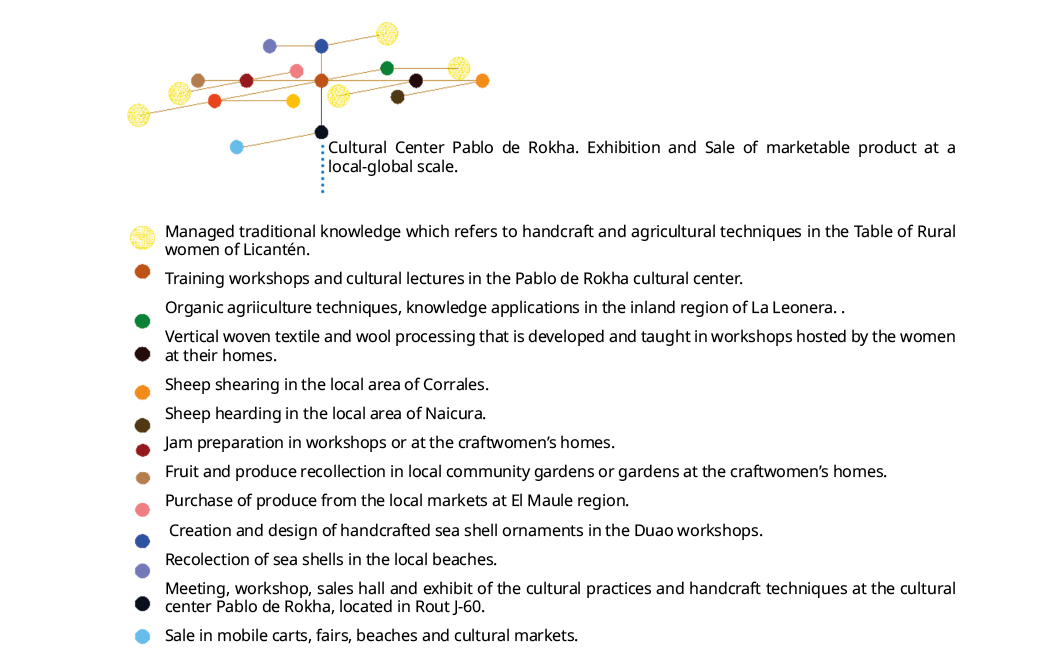

The second case of study is “Mesa de mujeres rurales de la comuna de Licantén, región del Muele, sur de Chile.” or “Board of rural women from Licanten, in the local region of Maule in the Southern Chile. This is a rural organization of women who live in southern Chile. Their T.K. is used to produce handcraft fruit jams, and Mapuche vertical woven textiles and sea shell decorative art, organic agriculture and traditional pottery in greda, or red clay. The diagram summarizes the interconnection amongst these activities and T.K. exchange within the territory (figure 4) and it is applicable to the framework that conforms this organizationand its T.K. Evidently, these communities occupy specific territories. In this case, the occupancy of the territory takes place in the Mataquito River Basin (figure 6). This network develops into a system of joint comercial exchange that functions as an organization.

Figure 6. General system that defines the scope of the project “Mesa de Mujeres Rurales de Licantén” or Board of Rural Women in Licantén. It defines the activation of local units and a structure of traditional knowledges in the area of the Mataquito River Basin. Source: Rosas-Bustos, 2014, p. 466.

This local unit and territorial organization comes from a series of T.K. formulated according to the production from a specific territory. This land or territory tells a cultural story stemming from the indigenous heritage. It is evident (image 11), that as these items are sold and comsumed elements and symbols are exchanged between sellers and buyers. The clay artisan women from Licanten incorporate weaving symbols on looms and iconography of Mapuche origin, giving a proper meaning to the expression of their art from their interpretation.

Their work transmits artistic messages of cultural expression. Another evidence of T.K. exchange takes place in the handcraft of pottery and leather, (image 13). The protector of the Virgen del Rosario in the traditional celebration in the Mataquito River Basin is called “Baile de los negros de Lora” or “Dance of peoples from African Descent from Lora.” This particular celebration centers on Virgin del Rosario.

Some of the pottery and figurines handcrafted leave a trace that reminds handcrafters and consumers of these cultural traditions.

In this particular case, one must take into consideration the network that spreads over the territory that houses this women’s organization. The application of the framework for interconnection and exchange of traditional knowledge facilitate an investment of resources to develop a process of sustainable management of this local territory.

Evaluation of such activities that facilitate this interconnection and exchange is imperative. In order to increment the activity and to generate both new forms of production and development, it is crucial to turn the T.K. into patrimony and resources for this community’s future development.

Image 11. Clay pot in preparation with engraving of the interpreted symbol of the Mapuche cultrún.

Source: Adriana Maureira.

Figure 7. Location map of the territory of Lora where the “black dance” party is held. Source: http://www.turismovirtual.cl/

Image 12. The Encuerado dance protects the Virgin. Women dressed in costumes for the “Baile de los negros” dance. Source: Maureira y Calquín, 2012, p.106.

Image 13. Red clay figurines that represent the leatherman, a character from the “baile de los negros de Lora dance” These figurines were handcrafted by Adriana Maureira. This is a handicraft product from the Board of Rural Women from Licantén or “Mesa de Mujeres Rurales de Licantén.” Source: Author.

CONCLUSION

Finally, this article calls for an operative definition of the T.K. born from the need to seek strategies of management: turning these T.K. into patrimony and resources for rural and indigenous communities is essential to prevent rural-urban migration. It implies the production cycle of the T.K. inside the local territory under the configuration of “being” and “doing”, el “ser” y “hacer”. This premise can become an initial point for strategy implementation as a means to create viable routes for a sustainable management of this patrimony. Understanding the environmental scope of each system of knowledge and its systemic interaction is a preliminary step to anticipate their effective management. This approach will assist the decision-making process and it will also contribute to take the necessary steps to assure effectiveness. This aspect is useful when it comes to deciding what innovation or reinsertion projects are socially culturally, environmentally and economically profitable for the rural and indigenous communities.

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0