Philologia Hispalensis · 2025 Vol. · 39 · Nº 1 · pp. 255-276

ISSN 1132-0265 · © 2025. E. Universidad de Sevilla. · (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED)

INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE: CURRENT TRENDS AND CRITICAL DIMENSION

COMPETENCIA COMUNICATIVA INTERCULTURAL: TENDENCIAS ACTUALES Y DIMENSIÓN CRÍTICA

Jacqueline García Botero

Universidad del Quindío

Margarita Alexandra Botero Restrepo

Universidad del Quindío

Cristian Camilo Reyes-Galeano

Universidad del Quindío

mailto:ccreyes@uniquindio.edu.co

Yeray González-Plasencia

Universidad de Salamanca

Recibido: 25-07-2024 | Aceptado: 18-10-2024

Cómo citar: García Botero, J., Botero Restrepo, M. A., Reyes-Galeano, C. C. y González-Plasencia, Y. (2025). Intercultural communicative competence: current trends and critical dimension. Philologia Hispalensis, 39(1), 255-276. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/PH.2025.v39.i01.10

Abstract

This article reports a systematic review of Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC) in the field of foreign language teaching and learning with the aim of identifying tendencies in ICC research. Based on the PRISMA methodology (Urrútia & Bonfill, 2010), there was conducted an analysis of 79 research and reflection articles written between 2010 and 2022 which met all the criteria established in a search protocol. The search was developed in two phases. The first phase places emphasis on identifying various trends regarding ICC and the second one focused on the critical dimension of ICC. The analysis of all the studies lead to the identification of several challenges that could be assumed from future researchers: approaching ICC from a critical perspective, implementing innovative strategies for the development of ICC, analyzing ICC into policies and curriculums. The foray into this field broadens the view of what language teaching should be in the education of tomorrow.

Keywords: Intercultural Communicative Competence, foreign languages, PRISMA declaration.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta una revisión sistemática de la Competencia Comunicativa Intercultural (CCI) en el campo de la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras con el objetivo de identificar tendencias investigativas en la investigación de la CCI. Con base en la metodología PRISMA (Urrútia & Bonfill, 2010), se realizó un análisis de 79 artículos de investigación y reflexión escritos entre los años 2010 y 2022 que cumplieron con todos los criterios establecidos en un protocolo de búsqueda. La búsqueda se desarrolló en dos fases. La primera fase puso énfasis en las tendencias investigativas en el campo de la CCI y la segunda se centró específicamente en la dimensión crítica de la CCI. El análisis de todos los estudios condujo a la identificación de varios desafíos que podrían ser asumidos por los futuros investigadores: abordar las CCI desde una perspectiva crítica, implementar estrategias innovadoras para el desarrollo de la CCI, analizar las CCI en políticas y currículos. La incursión en este campo amplía la visión de lo que debería ser la enseñanza de idiomas en la educación del mañana.

Palabras clave: Competencia Comunicativa Intercultural, lenguas extranjeras, declaración PRISMA.

1. Introduction

Intercultural Communicative Competence (hereinafter, ICC), studied from the context of bilingual education, is a topic of growing interest in recent years, mainly due to the contemporary dynamics generated by globalization and by the post-pandemic society that brought along social, political, economic, and cultural changes that undoubtedly created new communication scenarios. Thus, migratory phenomena, the use of new technologies as mediation in the educational field and, hence, the study of bilingualism as a linguistic reality that permeates all the dynamics of the current society, particularly the school system, make the study of language contact relevant from different perspectives.

From a sociolinguistic perspective, the study of ICC allows the analysis of the complexity of language and the different scenarios of contact between languages-cultures and the linguistic and cultural riches that contribute to the understanding of the teaching and learning processes. From a psycholinguistic perspective, studying ICC makes possible the understanding of bilinguality, properly speaking, such as the individuals’ intercultural competence, self-recognition, cultural identity and, overall, the recognition of individuals and their abilities to communicate in an increasingly interconnected world.

This article offers a general panorama of ICC current tendencies identified in the literature making emphasis on all the studies that bring the critical dimension into discussion. This systematic review gives educators, researchers and policy makers challenges and opportunities in the field of foreign language education to better teaching and learning processes in every educational context.

2. Literature review

Although the literature uses the terms IC (intercultural communication) and ICC as synonymous, this article adheres to the ICC concept given that – as indicated by Byram (1997) – this is the term that involves the interaction with a foreign language. ICC has been defined by multiple authors as an ability to carry out adequate and effective communication with people from other cultures (Byram, 1997; Fantini & Tirmizi, 2006; Oliveras Vilaseca, 2000) and as an ability to communicate appropriately, bearing in mind affective, cognitive, and procedural dimensions (Bennett, 2008; Meyer, 1991; Vilá Baños, 2005; Wiseman, 2002). In this regard, Wiseman explains “ICC competence involves the knowledge, motivation and skills to interact effectively and appropriately with members of different cultures” (Wiseman, 2002: 208); on his part, Bennett describes ICC as “a set of cognitive, affective and behavioral skills and characteristics that support effective and appropriate interaction in a variety of cultural contexts” (Bennett, 2008: 97). Research on ICC proposes culture and identity as inseparable elements in bilingual processes (Borghetti, 2019; Herrera Pineda, 2018; Herrera-Torres & Pérez-Guerrero, 2021; Soto-Molina & Méndez-Rivera, 2021); the use of technology as innovative strategy to promote ICC effectively (Manzanares Triquet, 2020; Zadi et al., 2021); study of minority languages as strategy to strengthen cultural identity (Howard-Malverde, 1998; Sumonte, 2020); new instruments to analyze ICC (González Plasencia, 2019).

The study of ICC and its relationship with foreign language teaching and learning shows that 2021 is the year with most investigations reported in the literature (following the search protocol stablished)[1], as evidenced in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Number of publications consulted from 2010 to 2022

Note. Original research data.

Shen (2021) states that, although globalization has raised interest in the study of ICC, it was the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic that increased its study, mainly through the mediation of technology in the educational field, which allowed for greater interaction among different cultures. Recently, the study of ICC continues to gain interest, and a significant number of investigations now center their analysis on the critical dimension of ICC (Aguirre et al., 2022); pedagogical strategies for the development of ICC (Nguyen, 2022; Villegas Paredes et al., 2022); analysis of cultural aspects in the writing by college students (Castrillón-Hernández et al., 2022); and measurement instruments of the IC (Luo & Chan, 2022).

Thereby, this article introduces the analysis of different studies in the field of ICC and bilingual education, considering the following guiding questions:

- What are the research trends on the intercultural communicative competence (ICC) in the field of foreign language teaching?

- How is the critical dimension included in ICC studies?

3. Methodology

This section accounts for the methodological procedure carried out to develop the systematic review. It includes the explanation of the search protocol and the results obtained in each of the four steps developed (identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion).

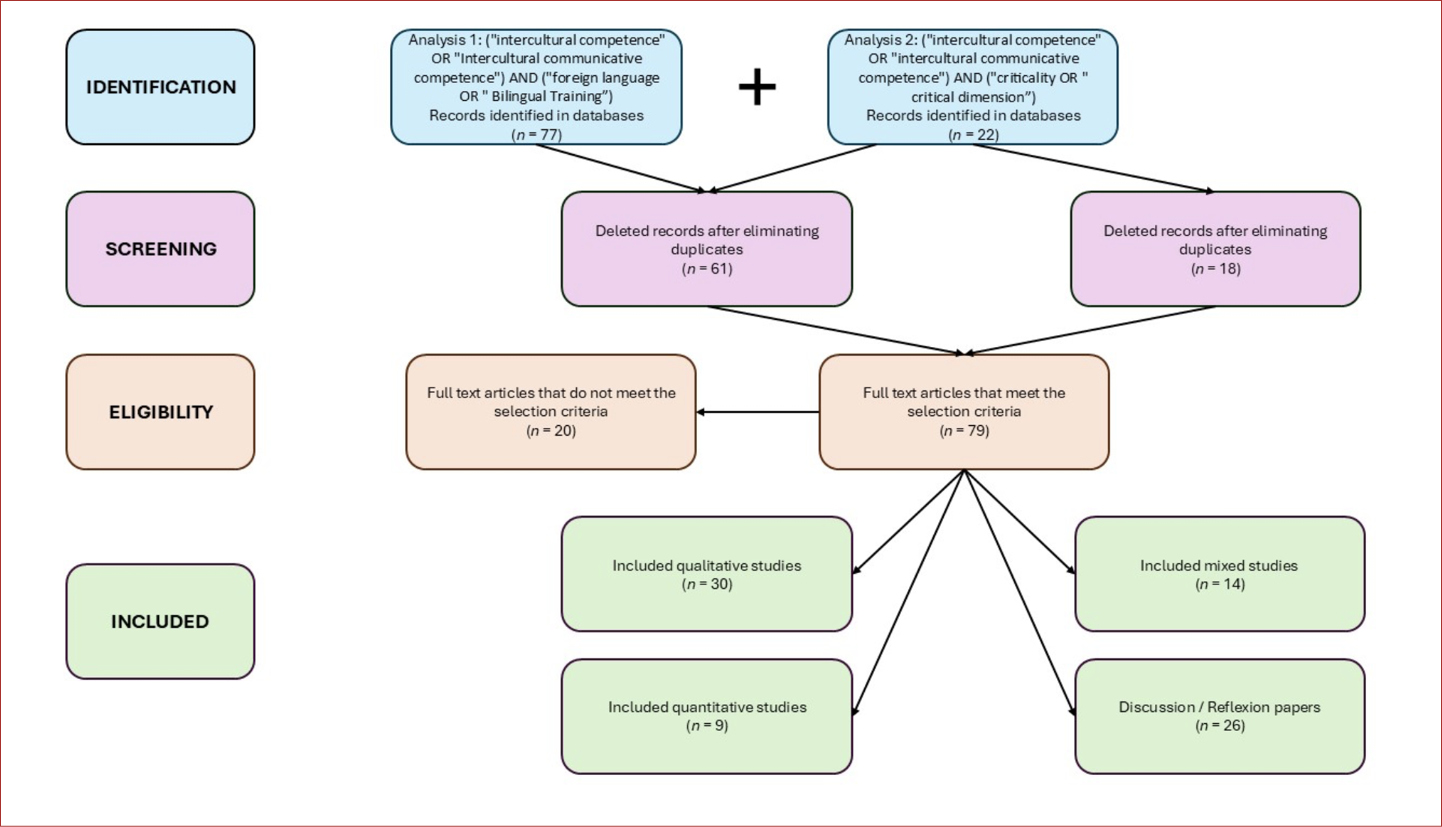

This systematic review adhered to the PRISMA declaration (Urrútia & Bonfill, 2010). The review was developed in two phases. The first one places emphasis on identifying various trends regarding ICC and the second one focused on the critical dimension of ICC. In both phases of the study, the protocol stablished the following inclusion criteria: studies conducted in English and Spanish on ICC, in all school contexts – nationally and internationally – since 2010 to the present and which followed the content variables established (ICC, foreign language, bilingual education/ critical dimension, criticality). The principal exclusion criterion established the fact of not having open access to the articles consulted.

3.1. Phase 1. ICC trends in foreign language teaching

In this phase the search strategy used was the following (“intercultural competence” or “Intercultural communicative competence”) and (“foreign language” or “Bilingual Training”).

- Step 1. Identification

The databases consulted in the identification process were: Academic search, EBSCO, Science Direct, J-gate, Scielo, Sage, Oxford and Scopus. Table 1 shows the number of articles identified.

Table 1

Data bases consulted in the first phase

|

Data bases |

Articles |

Percentages |

|

Academic search |

21 |

27,3% |

|

EBSCO |

20 |

26,0% |

|

Science Direct |

20 |

26,0% |

|

Other sources[2] |

16 |

20,8% |

|

TOTAL |

77 |

Nota. Original research data.

As shown in Table 1, a total of 77 articles were identified using the search strategy aforementioned. This first procedure was carried out considering the titles and abstracts of each study to determine their coherence with the criteria established.

- Steps 2 and 3. Screening and eligibility

In the process of screening (which includes the deletion of duplicates) and eligibility (which is a complete reading of the texts to verify the inclusion criteria) 16 articles were excluded. Thus, 61 articles were part of the study.

3.2. Phase 2. ICC and critical dimension

In the second phase, the search strategy used was (“intercultural competence” or “intercultural communicative competence”) and (“criticality” or “critical dimension”)

- Step 1. Identification

- Step 2 and 3. Screening and eligibility

- Jacqueline García Botero: Conceptualization, Data curation, Research, Methodology, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review.

- Cristian Camilo Reyes Galeano: Formal analysis, Data curation, Research, Methodology.

- Margarita Alexandra Botero Restrepo: supervision, visualization, editing.

- Yeray González Plasencia: supervision, visualization, editing.

- Jacqueline García Botero (author): conception of the idea, writer, editor.

- Margarita Alexandra Botero (author): writer, supervisor, editor.

- Cristian Camilo Reyes Galeano (author): writer, editor.

- Yeray González Plasencia (author): writer, supervisor, editor.

In the identification process it was possible to select a total of twenty-two (22) articles in the Web of Science (WOS), SCOPUS and Academic Search databases as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Data bases consulted in the second phase

|

Data bases |

Articles |

Percentages |

|

WOS |

8 |

36,36% |

|

SCOPUS |

6 |

27,28% |

|

Academic Search |

8 |

36,36% |

|

TOTAL |

22 |

Note. Authors’ creation.

In the process of screening and eligibility 4 articles were excluded because they corresponded to duplicates in the different databases. Thus, a total of 18 articles made part of the review. Figure 2 summarizes the process developed in the two phases.

Figure 2

Phase 1 and 2

Note. Authors’ creation.

As shown in the diagram, a total of 79 articles were included in both phases. In phase 1 several tendencies were identified, including: the countries where ICC is most studied, the methodology implemented in ICC studies, and the contexts where ICC is mostly analyzed; in phase 2 it was possible to analyze how is ICC from its critical dimension approached in FL settings.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Phase 1. ICC research trends

Addressing the first question: What are the research trends on the intercultural communicative competence (ICC) in the field of foreign language teaching? It was possible to identify several tendencies as shown below:

4.1.1. ICC and research methodologies

One of the first tendencies around ICC and bilingual education deals with the research methodology. Most of the studies in this field were conducted primarily from a qualitative perspective (n=25; 40,99%); few studies addressed said variable from a quantitative (n=9; 14,75%) or mixed perspective (n=11; 18,03%), and most of the papers corresponded to reflections and review papers (n=16; 26,23%).

Studies that focused on the qualitative and mixed synthesis inquired mainly on the attitudes, perceptions, and conceptions of students and/or teachers regarding the intercultural communicative competence, as in the research by Ponce de Leão (2018) who describes the perceptions, profile, and practice of nine teachers from schools in Portugal about ICC. The teachers in said context, according to the results, continue to grant relevance to the development of the communicative competence (focused on the linguistic competence) and assume that including the cultural aspect is time consuming; they express their desire to contribute to the development of ICC, but this is not reflected in their teaching practice because they have no clarity on the type of skills that must be developed in students to achieve said goal. Likewise, English teaching, in this context, is associated mainly with cultural aspects of the United States and the United Kingdom, leaving the other Anglophone countries out of study; this is evidenced in the materials chosen by the teachers. It is concluded, then, the need to train the teaching staff on ICC so they can bring it effectively to the classroom.

Żammit (2021) in her research with Maltese teachers reached similar conclusions. Although teachers showed a positive attitude with regards to the introduction of ICC, in their teaching practices there is no real didactic transposition in the classroom. The foregoing due to the lack of training in this topic. The author concludes by highlighting the need to develop intercultural skills in foreign language teachers so they can interact effectively with people from other cultures and, above all, so they can promote this skill in their students.

In this same line, Naidu (2020), in Australia, reported homogeneous findings in a qualitative study with 10 teachers of Indonesian as foreign language, which shows the need for formal training of teachers, given that although official documents and institutional policies recognize interculturality as an important aspect in the curriculum, confusion remains on the part of the teaching staff regarding the language-culture relationship and, hence, a conscious practice where culture is integrated into the teaching and learning processes is not carried out effectively.

From a mixed approach, and within the Colombian context, the study by Patiño Rojas et al. (2020) sought to identify beliefs and perceptions about the concept of ICC of 241 students from the third, fifth, seventh, and ninth semesters in the English-French foreign language career in a public university through a survey and a questionnaire of open questions for focal groups. From this research, it is concluded that there is a need to involve ICC in a more solid way to consolidate a critical interculturality and that future professors must be more informed about cultural aspects as central contents in the communication process. It also concludes that it is necessary to train professors in the field of foreign language teaching so they can consolidate into their practice the language-culture relationship.

From this same approach, the research by Permatasari & Andriyanti (2021) created an action plan to develop ICC among college students, given that it recognizes that many English professors, in Indonesia, do not integrate the teaching of the culture and use didactic and pedagogical materials that ignore the importance of cultural elements in teaching a foreign language. Shen (2021), also in the Asian continent, proposes a pedagogical strategy to develop ICC among college students by recognizing that “The persisting problem is that most of the scholars have focused more on language ability development while few have paid on ICC development” (Shen, 2021: 188); this author creates a model to teach ICC denominated “Online ICC Training Model”, which after its implementation proves having positive effects on the level of intercultural communicative competence of students.

In the case of quantitative research, the studies towards ICC primarily report the levels of this competence reached by teachers and students. It is the case of the research by Espinoza-Freire & León-González (2021) who analyzed, from the cognitive, procedural and affective dimension, the ICC level of 442 primary education teachers in Ecuador[3]. The study arrives at conclusions quite similar to those reported in qualitative and mixed studies; although the importance of ICC is recognized, there are still many weaknesses on how this knowledge is put into practice. Among the results of said study, medium to high level of knowledge is evidenced about the regulatory framework that supports intercultural education, but low level of knowledge about the methodologies incorporated in the classroom to develop ICC. In other words, the findings evidenced are not congruent among the dimensions; even though high percentages are observed in the cognitive and affective dimension, the opposite is evident in the procedural dimension. Alfonzo De Tovar (2020), with this same methodology and considering Fantini’s model (2006), assessed ICC from four dimensions: knowledge, skills, attitudes, and cultural awareness, and reports the impact of mobility programs in the development of ICC of college students in Spain. The results of this research highlighted the importance of intercultural instances or didactic strategies that permit contact between native and non-native students to improve the skills of intercultural speakers.

The reflection and discussion articles found in the literature emphasize on the analysis of critical interculturality in curricular policies and designs (García León & García León, 2014)); the importance of teacher training for the development of ICC (Quintriqueo et al., 2017); the need to develop ICC in the foreign language classroom (Fernández Sánchez-Alarcos, 2021; Noreña Peña & Cano Vásquez, 2020; Sánchez-Torres, 2014; Rico Troncoso, 2018); and the incorporation of new technologies as strategy to improve ICC (Abril Hernández, 2018; Hřebačková, 2019; McCloskey, 2012).

As aforementioned, studies on ICC in the field of foreign languages are carried out primarily under a qualitative methodology; There are few studies that approach this variable from a quantitative or mixed perspective; In this sense, González Plasencia (2020) proposes that given the nature of the components of the CCI, it would be advisable to use mixed methods that holistically capture the development of this skill.

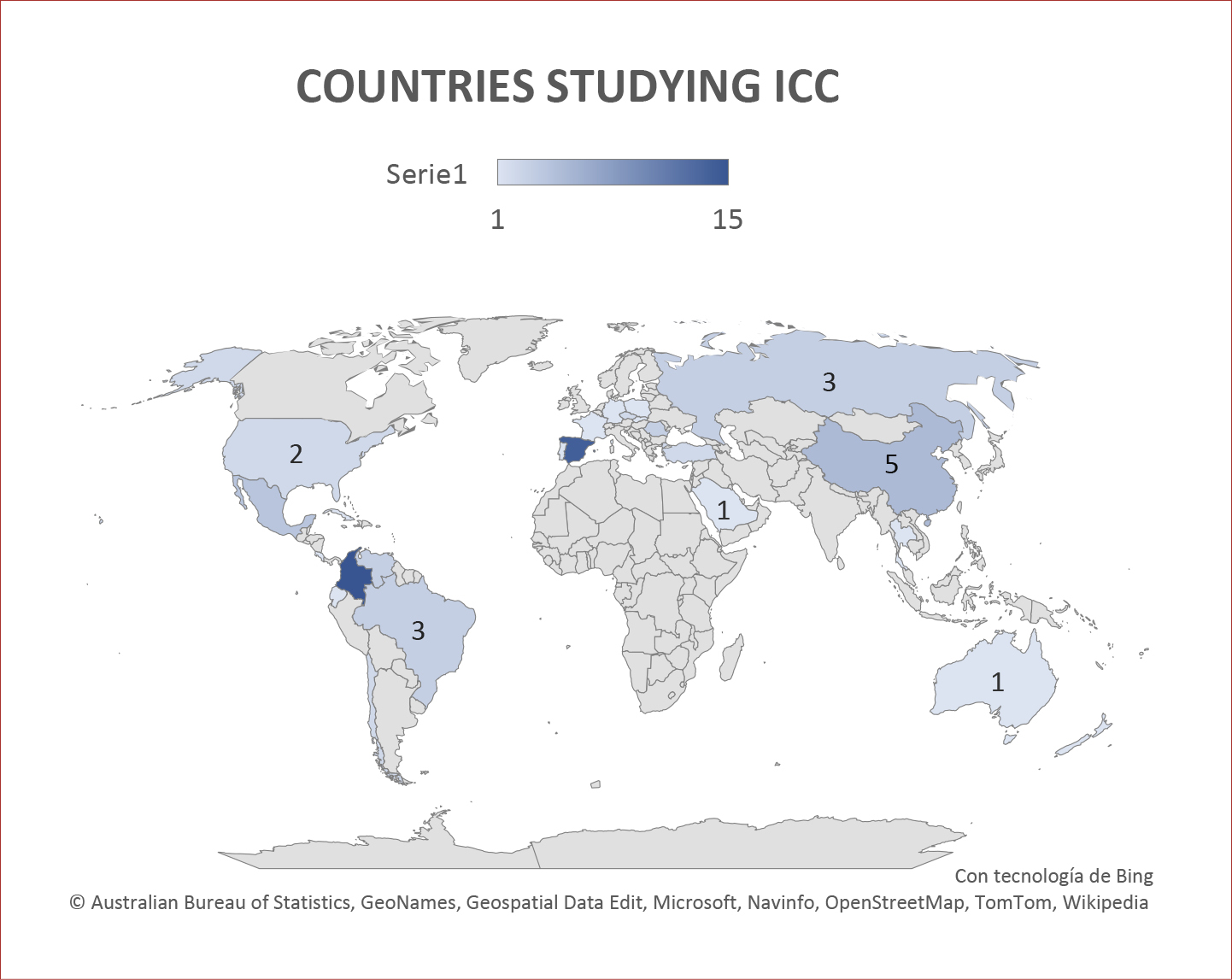

4.1.2. ICC and Geographic location

Another tendency found through this review deals with ICC and the geographic location of its studies, identifying many European and Latin American countries interested in this field as can be evidenced in Figure 3; this tendency, however, considers the fact that within the inclusion criteria established in the search protocol the languages Spanish, English and French were selected and some other studies might had been excluded due to this criterion.

Figure 3

ICC and geographic location

Note. Author’s creation.

For Latin American countries, like Bolivia, Chile, Cuba, Mexico, and Ecuador, emphasis is made on interculturality, but from the ethnic/indigenous communities or migration contexts (Howard-Malverde, 1998; Sumonte, 2020). For European countries, like Russia, Portugal, France, Rumania, Poland, and Slovakia, a very low number of investigations into ICC in the field of foreign language teaching and learning is reported in the databases consulted (as aforementioned, it might be related with the limitations of the language of the studies reviewed). Spain and Colombia are the countries that reported more research in this field, with 14 and 15 cases respectively, which represents 47,55%. In these contexts, many of the studies focus on the development of pedagogical or didactic proposals to promote ICC in foreign language classrooms. The research by Mejía & Agray Vargas (2014), for example, shows the experience of 10 Australian students of Spanish as a foreign language who lived an intercultural experience in situ. Through a short stay in Colombia, the authors demonstrate that these types of strategies permit foreign language students greater understanding about linguistic and cultural aspects that favor their intercultural communicative competence. Other strategies, such as telecollaborative experiences (Evaluate group, 2019; Villegas-Paredes et al., 2022), portfolios (López-Fernández, 2014), practice communities (Arismendi Gómez, 2021), and didactic strategies based on fictionality (Herrera Pineda, 2018), demonstrate that by making the academic community aware of the importance of recognizing culture (both their own and that of others), allows the development of intercultural skills that impact positively on the linguistic and cultural knowledge; that is, after implementing didactic and/or pedagogical proposals, there is an evident reconfiguration of concepts and classroom practices that favor the inclusion of intercultural speakers.

4.1.3. ICC and contexts of study

Now, considering the different contexts in which studies towards ICC were developed, it was possible to identify a different tendency, demonstrating that is the university context the focus for ICC researchers. The data collected from the 77 initial documents indicate that, in the university context a total of fifty-two (n=52; 67,53%) articles study ICC from this context, while in primary and secondary level a total of eleven (n=11; 14,28%) articles were identified; the 18.19% left correspond to articles directed to both contexts. Equally important, the search identified that most of the research on ICC is focused mainly on analyzing students (n=36; 46,75%) and teachers (n=33; 42,85%) separately, rather than in interaction (n=8; 10,4%).

Some of the articles in this tendency are the reflection by García León & García León (2014) and the reflection by Rico Troncoso (2018). The former proposes that critical intercultural educational is part of experiences and it should be always in the frame of a contextualized dialogue. In this sense, it is important for professors and students to recognize the importance of the language-culture relationship and it can be transcended, as the authors also suggest, to a bilingual education that is positioned in an emancipatory interest, that is, a critical perspective that transcends merely from linguistic and sociolinguistic knowledge to the pragmatic field; where it is not only possible to analyze reality but also to propose and make changes. The latter, proposes that communicative competence should not be the sole goal of language teaching; instead, intercultural abilities should be enhanced to better communication. The author also emphasizes in the need to recognize the language and culture relationship; arguments also proposed by the reflections by Barrera Vázquez & Cabrera Albert (2021), Martínez Lirola (2018) and Paricio Tato (2014).

4.2. Phase 2. ICC and the critical dimension.

Considering the second question of this review: How is the critical dimension included in ICC studies? There can be evidenced a strong tendency of research studies towards ICC in its critical dimension. Kumaravadivelu (2006) explained this critical turn as

The critical turn is about connecting the word with the world. It is about recognizing language as ideology, not just as system. It is about extending the educational space to the social, cultural, and political dynamics of language use, not just limiting it to the phonological, syntactic, and pragmatic domains of language usage. It is about realizing that language learning and teaching is more than learning and teaching language. It is about creating the cultural forms and interested knowledge that give meaning to the lived experiences of teachers and learners. (Kumaravadivelu, 2006: 70)

In this regards, several studies have been carried out, researching on diverse topics that approach this dimension: critical language awareness (Farias, 2005)[4], critical interculturality (Gutiérrez, 2022), citizenship education (Calle Díaz, 2017; Ahn, 2015), intercultural citizenship (Porto, 2013, 2019; Porto et al., 2018), Intercultural Service Learning (ISL) (Rauschert & Byram, 2018), critical intercultural communicative competence (Leal Rivas, 2020; Marimón Llorca, 2016), criticality (García Balsas, 2021; Parks, 2018), and critical cultural consciousness (Parks, 2019).

4.2.1. Critical Language Awareness

Farias’s reflection (2005) proposes the integration of critical language awareness (CLA) with critical pedagogy for teaching English as a foreign language. The author, who returns to the postulates of Fairclough & Donmall, defines CLA as that conscious recognition of the nature and function of language as a social practice, “the sensitivity of a person and his awareness of the nature of language and its role in human life” (Donmall, 1985 in Farias, 2005: 112). From critical pedagogy, and considering the contributions of Freire, the author emphasizes in three principles: 1) Teaching as emancipatory 2) Teaching focused on the recognition of difference 3) Teaching analyzed from power relations, especially in excluded sectors. In this sense, the author suggests that CLA and Critical pedagogy could have great benefits for understanding the complexity and richness of communication and language and empowers students to reflect on the nature and function of language in society. Furthermore, it proposes that a focus on critical awareness of language allows teachers to decentralize their practices from a grammatical perspective towards an inclusive of the social and political dimensions. The author proposes that English teachers could use the concentric circles model proposed by Kachru in 1985 to explore the implications of the spread of English in the world and establish the relationship between the center and the periphery.

In this same line of thought, and mainly considering power relations, the recognition of difference, equity and justice, Gutiérrez (2022) proposes approaching the teaching of English as a foreign language taking into account critical interculturality (CI). Starting from the basis that language and culture are dynamic and that language goes beyond representing a linguistic code, the author highlights the critical intercultural approach as a way of recognizing diversity, of generating spaces of criticism in which the appreciation of different perspectives is privileged, reversing prejudices and stereotypes, consolidating identities and recognizing the value of their own life stories and establishing an explicit connection of the importance between language and culture. This is how the author presents a didactic strategy implemented in her courses over a period of three years and shares with the academic community the work units she carried out to account for said intercultural approach. These units are based on the critical recognition of who we are and where we come from, exploring the origin of names (of each student), the effects of colonization, identities and diversity. It also explores the role and composition of contemporary families, the diversity of communities and the different ways in which many people are discriminated against and marginalized. The author concludes by highlighting that although this strategy can be improved by teachers and researchers, it is a starting point to understand how all the theoretical foundations can be put into practice in a meaningful way.

4.2.2. Critical Intercultural Communicative Competence

Now, focused on the teaching of Spanish as a foreign language (ELE), the critical dimension has been oriented towards the so-called “critical intercultural communicative competence (CCIC)”, a term that was born from the research of Marimón-Llorca (2016) and is taken up in the research by Leal Rivas (2020) but which has not been sufficiently explored from other research in the field of bilingual training and interculturality and which could receive great contributions from other perspectives. The ICCC is described by Marimón-Llorca as the expansion of ICC where language, discourse, society and diversity come together and as “a verbal and social «know-how» aimed at developing the ability to understand the language and interact from the individual understood as social actor” (Marimón Llorca, 2016: 199). From her study with 19 students learning Spanish as a foreign language, Marimón Llorca puts his concept of ICCC into practice by analyzing an opinion journalistic text based on four stages: 1) From the image to the words in which it is introduced essential vocabulary for the understanding of the text; 2) Approach to the textual organization from which aspects of syntactic order are analyzed to obtain a list of actors (subjects), actions (verbs), and values (adjectives); 3) Critical understanding of the text presenting the different perspectives on the main topic, and emphasizing those stereotypical visions to generate discussion; 4) Critical expression that implies the participation of students in the reconstruction of the text based on new syntactic and lexical combinations that allows them to assume a different perspective positioned from respect and cultural diversity. From this experience, the author concludes that the ICCC allows us to reflect on the role of language, its form and function in the construction of new perspectives.

From this same conception, and returning to the concept of ICCC proposed by Marimón Llorca (2016) and Leal Rivas (2020) conducted a research with Italian students learning Spanish as a foreign language whose objective was to analyze cognitive subprocesses in academic writing. From the functional dimension, this study starts from the recognition of language as a communication vehicle through which meanings are constructed and reconstructed. Similarly, the author recognizes intercultural communicative competence as a language learning that is consciously generated and that delves into linguistic and cultural diversity as part of the teaching and learning process. The author also positions critical intercultural communicative competence as a process that has its foundations in the communicative intention, in one’s own experience as a starting point for the reconstruction of meanings and in the understanding of the structure of the text that gives importance to the semantic, lexical, and grammatical logic of the organization of the text. From this research, it is concluded that approaching writing processes based on a critical understanding allows the improvement of cognitive subprocesses such as planning, textualization and revision.

4.2.3. ICC and citizenship education

Now, addressing the critical dimension of ICC from the conception of language teaching as a platform for the creation of global citizens, studies around citizenship education, intercultural citizenship and intercultural service-learning have generated different contributions to this dimension, as shown by research in the international context by Porto et al. (2018), Porto (2019), Ahn (2015) and Rauschert & Byram (2018). In 2018, Porto, Houghton and Byram report some studies that were part of a proposal for a special issue on intercultural citizenship education to a language teaching research journal. Considering Byram’s contributions, criticality is defined as the center of citizenship education since it allows conscious action that starts from self-reflection and personal and social transformation through intercultural dialogues. Thus, the studies reported by the authors discuss criticality, nativism, the intercultural speaker, loyalty to the nation-state, internationalism and action in the community, which are part of intercultural citizenship education.

The study by Uzum et al. (2017), for example, focused on the analysis of the use of inclusive and exclusive plural pronouns in multicultural education textbooks in the United States, concluding that there is a great need for textbooks’ creators to reflect the cultural and linguistic diversity of students and to promote a critical and reflective understanding of cultural and linguistic identities. In the case of nativism – which the authors define as a belief based on the fact that native speakers have superior linguistic competence and a deeper understanding of the culture associated with the language – Derivry-Plard’s study (2013) focused on the figure of the native language teacher in Japan and its impact on language teaching, concluding that the figure of the native language teacher can lead to discrimination and exclusion of non-native speakers in language teaching and that it is important to promote a critical and reflective understanding of linguistic and cultural identities in intercultural education. Another of the several investigations reported by Porto et al. (2018), focuses on intercultural service-learning. Thus, they return to the study of Wu (in Porto et al. 2018) who carried out a two-week experience with Taiwanese students in a Filipino community which allowed them to develop intercultural skills and have a significant impact on the life experience of the participants.

Another study reported by Porto (2018), in Argentina, showed a case study with seventy-six (76) Argentine students and twenty-three (23) British students (mostly) of foreign languages to promote language learning from the CLIL methodology (Content Integrated Learning and Foreign Languages) and it was also based on the development of intercultural citizenship. Based on a telecollaboration experience between students around a historical-social theme of interest to both contexts (the Falklands War). The author highlighted the theory of intercultural citizenship as a valuable tool to improve language teaching and promote intercultural understanding and attitudinal, procedural, and cognitive dimensions.

In Korea, based on the concept of intercultural critical consciousness – proposed by Byram – Ahn (2015) carries out an analysis of the teaching of English in immersion fields and suggests that although in these contexts the development of Intercultural citizenship, this is an important task for teachers and researchers, since it is possible to guide students to critically integrate into society and help their development through concrete actions. The author confirms the importance of equipping students to function in a diverse world, with the objective, among other things, of overcoming stereotypes, understanding otherness and promoting the understanding of their own cultural values.

Along the same lines, but in the Colombian context, Calle Díaz (2017) recognizes that bilingual training contexts are an appropriate scenario to promote the development of global citizenship since it is from these areas where greater diversity and confluence of different cultures can be evident. Likewise, the author suggests that the social and political dimensions should not be foreign to the educational field and that it is the role of the school to “educate good citizens” who assume a participation in the construction of society. In this sense, the author analyzes how Colombian policies contribute to the promotion of global citizenship and suggests that although basic standards for citizen competencies have been introduced in the curricula, which are based on peace and coexistence, democratic participation, plurality, identity and the appreciation of differences; and the chair for peace that lays its foundations in justice, human rights, the sustainable use of natural resources, historical memory, among others, the discourse is still far from practice in the classrooms. Furthermore, as the author analyzes, institutional policies adopt a superficial view of global citizenship and adopt basic levels of those proposed by UNESCO for its development in the classroom.

4.2.4. ICC oriented models

Finally, from the critical dimension of intercultural communicative competence, it was possible to identify studies that have contributed to the oriented models of the ICC. It is the case of the research of Parks (2018) who, based on research with students enrolled in a degree program in German at four universities in the United States and the United Kingdom, proposes a sixth knowledge to the framework provided by Byram: “knowing how to recognize oneself” (savoir se reconnaitre). This knowledge is defined by the author as:

The ability to critically reflect on the world and themselves from a perspective situated outside the learners’ own culture/cultures and that of the target culture (TC). Through this critical reflection, learners are able to recognise themselves as members of a society that is foreign to others and discover how their own beliefs, behaviours and discourse are comparably culturally marked. (Parks, 2018: 120)

In this way, Parks explains, the learner is situated in a multilingual perspective that allows him to reflect on his own culture(s) and the culture of the target language from “outside” his own perspective, allowing, in turn, to recognize his discourse as culturally comparable. The author, likewise, contributes a new element to literature: “communicative criticality,” which she describes as a new form of criticality that arises specifically from the learning of foreign languages in which there is a recognition of semiotic systems and linguistic aspects of the L1 and the FL, so that, based on the comparison and understanding of the limitations in one’s own language and in the foreign language, there can be a reconstruction of the “I” concomitantly with the development of said knowledge.

5. Conclusions

Responding to the initial research question: What are the research trends on intercultural communicative competence (ICC) in the field of foreign language teaching? The following trends may be proposed. In the first place, considering research methodologies, it was found that the qualitative approach prevails in ICC research related to the field of bilingual education. From this approach, teaching profiles and students and professors’ perceptions towards ICC are mainly analyzed. Overall, a homogeneous conclusion is observed in the different studies analyzed: there is minimum development of ICC in the classrooms due to, primarily, the lack of knowledge about the language-culture relationship, which leads to classroom practices focused on the development of linguistic skills and where cultural aspects are ignored or shyly and momentarily included.

Secondly, in the databases consulted, Spain and Colombia are the countries that in recent years have focused their research interest on interculturality and foreign language teaching. In these countries, different strategies have been explored to develop intercultural skills by using technology as a primary tool at the forefront of changes and situations imposed by current society. Thereafter, regarding the population studied in the field of interculturality, a dichotomous analysis is evident in most of the studies; that is, students and professors are analyzed separately, not in the same interaction; besides, the university context is the one that researchers study more. These findings represent a challenge for future research that seek to explore ICC from a holistic perspective and from different academic settings.

Considering the second question that guided this review, it was possible to analyze how ICC is introduced in language teaching. Thus, it could be evident that the importance of language awareness, citizenship education, critical interculturality, otherness, among many other constructs are nowadays leading the academic discussions. What the critical turn highlighted is the importance of moving from theory to practice, and the need of including ICC into educational policies and curriculums. For this to happen, teacher training is necessary so that the concept of ICC is strengthened from the conceptual, methodological, and didactic view. Recognizing the language-culture conceptual perspective will be the starting point to develop ICC; without this recognition, the task of transcending to teaching from the merely linguistic view would be difficult to solve. A call is made for the development of intercultural values in foreign language classrooms from the recognition of the self to the recognition of others.

All these findings highlight the importance of going beyond conventional language teaching and promoting a critical and intercultural approach that connects language learning with a deeper understanding of the social, political and cultural dynamics of societies. Language teaching based on intercultural communicative competence from its critical dimension allows the construction of active citizens, who assume a critical and reflective role to face society’s problems.

Credit Author contribution statement

Authors’ contribution

References

Abril Hernández, A. (2018). Edublogs in Foreign Language Teaching: Integrating Language and Culture. Letral, (20). http://hdl.handle.net/10481/59113

Aguirre, F., Cardona, E., Vargas, D., Villa, V. & Herrera, J. (2022). Análisis crítico del impacto del MCER en las competencias interculturales de los estudiantes de décimo semestre del programa de Licenciatura en Lenguas Modernas de la Universidad del Quindío a partir de los criterios establecidos por Amandine Denimal, Francois Rastier a y Catherine Walsh. Revista de Investigaciones Universidad Del Quindío, 34(1), 12-21.

Ahn S. Y. (2015). Criticality for Global Citizenship in Korean English Immersion Camps. Language and Intercultural Communication, 15(4), 533-549. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2015.1049612

Alfonzo De Tovar, I. C. (2020). Desarrollo de la competencia intercultural en contextos prurilingües y pluriculturales: programa universitario de movilidad idiomática. Tonos Digital, (38).

Arismendi Gómez, F. A. (2021). Formación de formadores de lenguas extranjeras en educación intercultural por medio de una comunidad de práctica. Folios, (55), 199-220. https://doi.org/10.17227/folios.55-12893

Barrera Vázquez, S. & Cabrera Albert, J. (2021). Culture, Interculturality and Education: Referents of the Teaching-learning of Foreign Cultures. Mendive, 19(3), 999-1013.

Bennett, J. M. (2008). Transformative Training: Designing Programs for Culture Learning. In Contemporary Leadership and Intercultural Competence: Understanding and Utilizing Cultural Diversity to Build Successful Organizations (pp. 95-110). Sage.

Borghetti, C. (2019). Interculturality as Collaborative Identity Management in Language Education. Castledown, 2(1), 20-38. https://doi.org/10.29140/ice.v2n1.101

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Multilingual Matters.

Castrillón-Hernández, P., García-Ruiz, J., Gutierrez-Ceballos, L., Morales-Palacios, M. & Tovar-Lopez, M. (2022). Convenciones culturales y tipos de modalidad en la producción escrita argumentativa, género columna de opinión, en L1, L2 y L3 de estudiantes de IX semestre de la licenciatura en lenguas modernas de la universidad del Quindío: Un estudio de caso. Revista de Investigaciones Universidad Del Quindío, 34(1), 536-541.

Calle Díaz, L. (2017). Citizenship Education and the EFL Standards: A Critical Reflection. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’. Professional Development (Philadelphia, Pa.), 19(1), 155-168. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.55676

Derivry-Plard, M. (2013). The Native Speaker Language Teacher: Through Time and Space. In S. A. Houghton & D. J. Rivers (Eds.), Native-speakerism in Japan: Intergroup Dynamics in Foreign Language Education (pp. 243-255). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.27080058.24

Espinoza-Freire, E. E. & León-González, J. L. (2021). Intercultural Competences of Primary Education Teachers in Machala, Ecuador. Información Tecnológica, 32(1), 187-198. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07642021000100187

Evaluate group. (2019). Evaluating the Impact of Virtual Exchange on Initial Teacher Education. Research Publishing Net. https://www.unicollaboration.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/EVALUATE_EPE_2019_v2.pdf

Fantini, A. & Tirmizi, A. (2006). Exploring and Assessing Intercultural Communication. World Learning Publications.

Farias, M. (2005). Critical Language Awareness in Foreign Language Learning. Literatura y Lingüística, (16), 211-222. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0716-58112005000100012

Fernández Sánchez-Alarcos, R. (2021). En torno a la noción de interculturalidad en la enseñanza de segundas lenguas: Didáctica cultural, hermenéutica y literatura. Hispanic Research Journal, 21(3), 207-220. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682737.2020.1874711

García Balsas, M. (2021). Interculturalidad, dimensión crítica y lengua en uso: análisis de producciones textuales de aprendices de ELE. Tonos Digital, (41).

García León, D. & García León, J. (2014). Educación bilingüe y pluralidad: Reflexiones en torno de la interculturalidad crítica. Cuadernos de Lingüística Hispánica, (23), 49-65. https://doi.org/10.19053/0121053X.2338

González Plasencia, Y. (2019). Comunicación intercultural en la enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/b16100

González Plasencia, Y. (2020). Instrumentos de medición de la competencia comunicativa intercultural en español LE/L2. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 7(2), 163-177. https://doi.org/10.1080/23247797.2020.1844473

Gutiérrez, C. (2022). Learning English From a Critical, Intercultural Perspective: The Journey of Preservice Language Teachers. Profile: Issues in Teachers’. Professional Development (Philadelphia, Pa.), 24(2), 265-279.

Herrera Pineda, J. (2018). La ficcionalidad como estrategia didáctica en el desarrollo de la competencia comunicativa intercultural en las lenguas extranjeras. Lenguaje, 46(2), 242-265. https://doi.org/10.25100/lenguaje.v46i2.6582

Herrera-Torres, D. M. & Pérez-Guerrero, C. M. (2021). ¿Cómo fomentar la competencia comunicativa intercultural desde el enfoque por tareas? Pro-Posições, 32(1), 1-32.

Howard-Malverde, R. (1998). Grasping Awareness: Mother-tongue Literacy for Quechua Speaking Women in Northern Potosí, Bolivia. International Journal of Educational Development, 18(3), 181-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-0593(98)00004-2

Hřebačková, M. (2019). Teaching Intercultural Communicative Competence through Virtual Exchange. Training. Language and Culture, 3(4), 8-17.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). TESOL Methods: Changing Tracks, Challenging Trends. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 59-81. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264511

Leal Rivas, N. (2020). Critical Intercultural Communicative Competence: Analysis of Cognitives Sub-processes in Academic Writing Samples in University Students of Spanish Foreign Language (Sfl). Porta Linguarum, (34), 169-192. https://doi.org/10.30827/portalin.v0i34.16739

López-Fernández, O. (2014). University Teaching Experience with the Electronic European Language Portfolio: An Innovation for the Promotion of Plurilingualism and Interculturality / Experiencia docente universitaria con el Portfolio Europeo de Lenguas electrónico: una innovación para la promoción del plurilingüismo y la interculturalidad. C&E, Cultura y Educación, 26(1), 211-225. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2014.908667

Luo, J. & Chan, C. K. Y. (2022). Qualitative Methods to Assess Intercultural Competence in Higher Education Research: A Systematic Review with Practical Implications. Educational Research Review, 37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100476

Manzanares Triquet, J. C. (2020). Gamification, a Novel Pedagogical Method to Overcome the Challenge of Teaching Spanish in Chinese Universities. Publicaciones de La Facultad de Educación y Humanidades Del Campus de Melilla, 50(3), 271-309.

Marimón-Llorca, C. (2016). Hacia una dimensión crítica en la enseñanza de español como lengua extranjera: La Competencia Comunicativa Intercultural Crítica (CCIC). Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada, 29(1), 191-211. https://doi.org/10.1075/resla.29.1.08llo

Martínez Lirola, M. (2018). La importancia de introducir la competencia intercultural en la educación superior: propuesta de actividades prácticas. Revista Electrónica Educare, 1-19. https://www.scielo.sa.cr/pdf/ree/v22n1/1409-4258-ree-22-01-40.pdf

McCloskey, E. M. (2012). Global Reachers: A Model for Building Teachers’ Intercultural Competence Online. Comunicar, 19(38), 41-49. https://doi.org/10.3916/C38-2012-02-04

Mejía, G. & Agray-Vargas, N. (2014). Intercultural Communicative Competence in SFL Immersion Courses, an Experience with Australian Students in Colombia. Signo y Pensamiento, 33(65), 104-117. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.SYP33-65.lcci

Meyer, M. (1991). Developing Transcultural Competence: Case Studies of Advanced Foreign Language Learners. In D. Buttjes & M. Byram (Eds.), Mediating Languages and Cultures: Towards and Intercultural Theory of Foreign Language Education (pp. 136-158). Multilingual Matters.

Naidu, K. (2020). Attending to ‘Culture’ in Intercultural Language Learning: A Study of Indonesian Language Teachers in Australia. Discourse (Berkeley, Calif.), 41(4), 653-665.

Nguyen, H. T. T. (2022). Empowering Intercultural Communication Competence for Foreign Language-Majoring Students through Collaboration-Oriented Reflection Activities. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 11(1), 110-122.

Noreña Peña, D. & Cano Vásquez, L. (2020). Interculturalidad, enseñanza y aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera. El papel del docente. Revista Q, 11(22), 74-84.

Oliveras Vilaseca, A. (2000). Hacia la competencia intercultural en el aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera. Edinumen.

Paricio Tato, S. (2014). Competencia intercultural en la enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras. Porta Linguarum, (21), 215-226. https://www.ugr.es/~portalin/articulos/PL_numero21/14%20%20Silvina.pdf https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.30491

Parks, E. (2018). Communicative Criticality and Savoir se Reconnaître: Emerging New Competencies of Criticality and Intercultural Communicative Competence. Language and Intercultural Communication, 18(1), 107-124. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2017.1401691

Parks, E. (2019). The Separation between Language and Content in Modern Language Degrees: Implications for Students’ Development of Critical Cultural Awareness and Criticality. Language and Intercultural Communication, 20(1), 22-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2019.1679161

Patiño Rojas, D. M., Conde Borrero, C. & Espinosa González, L. (2020). Creencias y percepciones de los estudiantes sobre la competencia comunicativa intercultural del programa de Licenciatura en Lenguas Extranjeras de la Universidad del Valle. Folios, 53. https://doi.org/10.17227/folios.53-8001

Permatasari, I. & Andriyanti, E. (2021). Developing Students’ Intercultural Communicative Competence through Cultural Text-based Teaching. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11(1), 72-82. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v11i1.34611

Ponce de Leão, A. (2018). Interculturality in English Language Teaching. Via Panorámica: Revista de Estudios Anglo-Americanos, 7(2), 1646-4728. https://ojs.letras.up.pt/index.php/et/article/view/5070

Porto, M. (2013). Language and Intercultural Education: An Interview with Michael Byram. Pedagogies, 8(2), 143-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2013.769196

Porto, M. (2018). Does education for Intercultural Citizenship Lead to Language Learning? Language, Culture and Curriculum, 32(1), 16-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2017.1421642

Porto, M. (2019). Does education for intercultural citizenship lead to language learning? Language, Culture and Curriculum, 32(1), 16-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2017.1421642

Porto, M., Houghton, S. A. & Byram, M. (2018). Intercultural Citizenship in the (Foreign) Language Classroom. Language Teaching Research, 22(5), 484-498. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817718580

Quintriqueo, S., Torres, H., Sanhueza, S. & Friz, M. (2017). Competencia Comunicativa Intercultural: Formación de profesores en el contexto poscolonial chileno. Alpha (Osorno), (45), 235-254. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-22012017000200235

Rauschert, P. & Byram, M. (2018). Service Learning and Intercultural Citizenship in Foreign-Language Education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 48(3), 353-369. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2017.1337722

Rico Troncoso, C. (2018). The Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC) in the Contexts of Teaching English as a Foreign Language. Signo y Pensamiento, 37(72), 77-94.

Sánchez-Torres, J. (2014). Interculturality in the English Subject at the Spanish/English Bilingual Schools of Seville, Spain. Elia, 14(1), 67-96.

Shen, L. (2021). An Investigation of Learners’ Perception of an Online Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC) Training Model. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 16(13), 186-200. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v16i13.24389

Soto-Molina, J. E. & Méndez-Rivera, P. (2021). Flipped Classroom to Foster Intercultural Competence in English Learners. Panorama, 15(29), 32-51. https://doi.org/10.15765/pnrm.v15i29.1706

Sumonte, V. (2020). Developing Intercultural Communicative Competence in a Haitian Creole Language Acquisition Program in Chile. Ikala, 25(1), 155-169. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v25n01a09

Urrútia, G. & Bonfill, X. (2010). Declaración Prisma: Una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Medicina Clínica, 135(11), 507-511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2010.01.015

Uzum, B., Yazan, B. & Selvi, A. F. (2017). Inclusive and Exclusive Uses of We in Four American Textbooks for Multicultural Teacher Education. Language Teaching Research, 22(5), 625-647. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817718576

Vilá Baños, R. (2005). La competencia comunicativa intercultural. Un estudio en el Primer Ciclo de la ESO. Universitat de Barcelona.

Villegas-Paredes, G., Canto, S. & Rodríguez Moranta, I. (2022). Telecolaboración y competencia comunicativa intercultural en la enseñanza-aprendizaje de ELE: un proyecto en educación superior. International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Learning, (4), 97-118. https://doi.org/10.30827/portalin.vi.21446

Wiseman, R. (2002). Intercultural Communication Competence. In E. B. Gudykunst & B. Mody (Eds.), Handbook of International and Intercultural Communication (pp. 207-224). Sage.

Zadi, I. C., Montanher, R. C. & Monteiro, A. M. (2021). Digital Game for Learning English as a Second Language using Complex Thinking. Revista Científica General José María Córdova, 19(33), 243-262. https://doi.org/10.21830/19006586.727

Żammit, J. (2021). Maltese as a Foreign Language Educators’ Acquisition of Intercultural Capabilities. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-021-00116-3

[1] This search protocol is explained with more detailed in the Methodology section (§ 3).

[2] J-gate, Scielo, Sage, Oxford, Scopus.

[3] The instrument used was a questionnaire of 34 questions grouped in every dimension and organized in a Likert scale from 0 to 10. The questionnaire was expert validated and piloted in the studied context. To determine the reliability of the instrument the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient test was conducted.

[4] This publication is not included in the sample of research analyzed for the selected period. However, we consider it necessary to cite this work given its relevance and influence with respect to “critical language Awareness” in the subsequent decade, as illustrated in the following section.