https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/PH.2020.v34.i07.07

Marina Mozzon-McPherson

The University of Hull

m.mozzon-mcpherson@associate.hull.ac.uk

Maria Giovanna Tassinari

Freie Universität Berlin

Giovanna.Tassinari@fu-berlin.de

ORCID: 0000-0002-1878-454X

Recibido: 17-06-2020

Aceptado: 01-09-2020

Publicado: 17-12-2020

https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/PH.2020.v34.i01.07

Abstract

This article examines the development of the practice of advising in language learning (ALL) and the related establishment of a distinctive role for language learning advisors (LLAs) in the context of Modern Languages in Higher Education. It firstly defines ALL, its principles and interdisciplinary contributions to the construction of reflective dialogue which lies at the heart of advising; these come, inter alia, from counselling, psychology, and coaching. Secondly, it discusses the gradual shift from two distinctive practices (language teaching and advising for language learning) to a more highly integrated academic practice which utilises intentional, skilful reflective dialogue as its distinctive professional feature for successful, sustained, learning conversations. Thirdly, it illustrates this shift through advisors’ professional development stories and their professional needs. Finally, it identifies areas for further research and professional preparation of ALL practitioners and concludes by reflecting on the challenges facing universities, and the positive contribution which ALL can make to address them.

Key words: Advising in language learning, language learning advisors, reflective dialogue, advising skills and competences.

Resumen

En este artículo se examina el desarrollo de la práctica del asesoramiento en el aprendizaje de idiomas (ALL, Advising in Language Learning) y el consiguiente establecimiento de una función distintiva para los asesores en el aprendizaje de idiomas (LLAs, Language Learning Advisors) en el contexto de las lenguas modernas en la enseñanza superior. En primer lugar, se define la ALL, sus principios y aportaciones interdisciplinares a la construcción de un diálogo reflexivo en el centro del asesoramiento; estas provienen, entre otros, del asesoramiento, de la psicología y del coaching. En segundo lugar, se analiza el cambio gradual desde dos prácticas distintivas (la enseñanza de idiomas y el asesoramiento para el aprendizaje de idiomas) a una práctica académica más integrada que utiliza el diálogo reflexivo intencional y eficaz como característica profesional distintiva para diálogos pédagogicos eficaces y continuos. . En tercer lugar, se ilustra este cambio a través de los relatos de desarrollo profesional de los asesores y sus necesidades profesionales. Por último, se identifican las áreas en las que se debe seguir investigando y preparando profesionalmente a los especialistas de ALL y se concluye con una reflexión sobre los retos a los que se enfrentan las universidades y la contribución positiva de ALL puede para abordarlos.

Palabras clave: Asesoramiento en el aprendizaje de idiomas, asesores en el aprendizaje de idiomas, diálogo reflexivo, habilidades y competencias de asesoramiento.

For more than three decades advising for language learning (hereafter ALL) has been part of the language teaching and learning and second language acquisition landscape in the Higher Education context (Riley 1997; Mozzon-McPherson & Visman 2001; Rubin 2007; Mynard & Carson 2012; Shelton-Strong 2020). However, its place both in practice and research is still that of a minor sister. Some language teachers are wary, if not suspicious, of advising, seeing it as a potential competitor to ‘proper’ language teaching. Moreover, with some exceptions, senior management in universities tend to see it as a less expensive alternative to teaching and, consequently, it may become confined to an academic service of self-access centres. These attitudes and reservations are partly due to misconceptions of what advising is, how it can support learners in the development of their language skills and develop their competence in self-regulation and autonomy (Dickinson 1992; Lamb 2000; Little 2007). In recent decades, reflection on existing ALL practice and related research have, however, contributed to addressing such misconceptions by shedding light on the peculiar nature and principles of advising, its theoretical foundations, its varied applications, and its impact on learners, the learning process and teaching (Gremmo 1995, 2009; Carette & Castillo 2004; Mozzon-McPherson 2012; Kato & Mynard 2016; Tassinari 2017).

To this end, this article focuses on the personal and professional development required to become an advisor, and the challenges and opportunities which the shift from a teacher-student perspective to an advisor-advisee relationship can offer. We start by briefly defining ALL and subsequently illustrate the advisors’ competences and skills needed to engage in the intentional use of reflective dialogue which is at the core of the advising process (Gremmo 2011; Mozzon-McPherson 2019). We then provide insights into the principles of reflective dialogue followed by a brief excursus on how experienced language learning advisors describe their journey from teaching to advising. We conclude by reflecting on how advising principles can be integrated into a new approach to language teaching.

As a relatively new form of pedagogical interaction, mostly a one-to-one interaction between a learner (advisee) and an advisor (cf. Clemente 2003: 201), ALL aims at supporting learners as they become aware of their learning process, and transforms it in order to learn effectively according to their needs, goals and the opportunities offered by their social and learning environments. An integral part of the advising process is encouraging the learner to reflect upon their unique learning experience; this includes cognitive, metacognitive and affective dimensions which raise awareness, foster decision-making and enhance personal transformation. Such reflective engagement ultimately contributes to fostering learner autonomy, as the capacity to control one’s own language learning process in the afore mentioned dimensions (Benson 2011).

Core to ALL is the pedagogical dialogue (see Section 4), co-constructed by advisor and advisee, which is key to the advising process. Inherent in this is the advisor’s ability to remain open to the encounter with each advisee, to actively listen and to encourage them, mindful of the advisor’s own learning habits and biases. This process may also include helping the learner with relevant conceptual and methodological information, suggesting specific tools to enhance reflection and promote self-regulation and providing motivational and psychological support, if necessary (see, among others, Gremmo 1995, 2009; Carette & Castillo 2004; Mozzon-McPherson 2012; Kato & Mynard 2016; Tassinari 2016).

Just as with trying to define something as abstract as autonomy in language learning (Benson, 2011), any definition of ALL can only be general, since approaches to advising may differ considerably. In some HE contexts, ALL may be offered as an optional, additional component to a formal language course. Alternatively, it may constitute support for self-directed learning in self-access settings, either in the form of face-to-face sessions or online. In others, it may be integrated in an autonomous language learning module (cf. the ALMS modules at the University of Helsinki Language Centre, Karlsson, Kijsik, & Nordlund 1997). Advising can also be offered either for language learning in general, or for specific skills such as writing or pronunciation (Carson & Mynard 2012). In addition, ALL may range from strictly non-directive to more directive approaches (Spänkuch & Kleppin 2014). As Ciekanski observes “even if advisors share the same professional definition of what an advising relationship is, this definition is constantly renegotiated in relation to the context and to each learner. The notion of collaboration is fundamental to the pedagogical approach to autonomy, and collaborative practices between advisor and learner are encouraged by the very structure of the advising interaction’” (Ciekanski 2007: 125).

The process of scaffolding learning through the use of intentional reflective dialogue, which lies at the heart of advising, draws on its background from various theoretical frameworks from sociocultural theories (Lantolf & Thorne 2007) to client-centred counselling in humanistic psychology (Rogers 1951) and systemic coaching (Gray 2007; Spänkuch 2014; Whittington 2016).

Competences and skills are closely intertwined in ALL, and mapping the journey from language teacher to language learning advisor requires a careful examination of the transition from one to the other, and the identification of the attributes which facilitate such a transition and inform the related professional development of advisors. By competence we mean the overarching, integrated framework of skills, knowledge and abilities; this definition provides us not only with the ‘what’, but importantly the ‘how’, and within the ‘how’ it offers a qualitative measure to evaluate competence. Consequently, it informs the necessary training to form competent advisors or to integrate successful advising into other existing jobs and contexts.

Through a comprehensive review of ALL research, four core competences stand out (see Figure 1). These will be further examined in combination with the skills which support them. Placed in this new setting, when engaged in what are predominantly individual learning conversations, advisors initially focused their work on cognitive and metacognitive skills and strategies to help learners learn (Oxford 1990, 2017; Cohen 1998). This emphasis aligned with research into learner autonomy which was primarily led by educational research (Dickinson 1992; Lamb 2000; Little 2007) whose focus was on aspects of the management of learning, learners’ needs, learning styles, and task design to help learners achieve their intended goals.

Figure 1. ALL Competences.

Consequently, initial competence in ALL stressed conceptual knowledge of: 1. One, or more, foreign languages; 2. Language learning strategies (how to learn); 3. Breadth of resources and technologies (for example the context and tools for learning in a self-access centre).

As the practice of advising grew, advisors’ needs shifted in emphasis to the transformative nature of learning conversations (see the seminal work by Kelly 1996). This more closely linked the practice of advising to that of counselling (Rogers 1951; Egan 1998) and identified a useful set of macro and micro skills as a necessary framework to successfully enable a process of transformation in learning (see Table 1). This is a fundamental shift which called for the need to look for other forms of enquiry in disciplines other than education and started a gradual, distinctive trajectory of advising practices away from teaching.

|

Macro-skills |

Micro-skills |

|

1. Initiating: Introducing new directions and options |

10. Attending: Giving the learner undivided attention |

|

2. Goal-setting: Helping the learner to formulate specific goals and objectives |

11. Restating: Repeating in own words what the learner says |

|

3. Guiding: Offering advice and information, direction and ideas, and suggesting |

12. Paraphrasing: Simplifying the learner’s statements by focussing on the essence of the message |

|

4. Modelling: Demonstrating target behaviour |

13. Summarising: Synthesising the main elements of a message |

|

5. Supporting: Providing encouragement and reinforcement |

14. Questioning: Using open questions to encourage self-exploration |

|

6. Giving feedback: Expressing a constructive reaction to the learner’s efforts |

15. Interpreting: Offering explanations for learner experiences |

|

7. Evaluating: Appraising the learner’s process and achievement |

16. Reflecting feelings: Surfacing the emotional content of learner statements |

|

8. Linking: Connecting the learner’s goals and tasks to wider issues |

17. Empathising: Identifying with the learner’s experience and perception |

|

9. Concluding: Bringing a sequence of works to a conclusion |

18. Confronting: Surfacing discrepancies and contradictions in the learner’s communication |

A wealth of studies (Mozzon-McPherson & Visman 2001; Rubin 2007; Gremmo 2009) started to examine the skills engaged in advisor-advisee dialogic interaction and their related, effective use by experienced advisors. This came to form the foundations of the first specific Postgraduate Qualification in Advising for Language Learning delivered by the University of Hull (2001-2010). The qualification also highlighted the need to gather audio and visual recordings and/or transcriptions of advising sessions in order to describe and observe advising in action (Mynard & Carson 2012; Ludwig & Mynard 2012; Kato & Mynard 2016) and systematically analyse advising discourse in an attempt to measure the impact on learning, identify the qualitative aspects of this approach in facilitating a positive and effective language learning experience, document successful uses of specific interventions, and map the contributing skills to inform further professional development.

On the part of the advisor, the skilful dialogic application of both Kelly’s macro and micro skills requires an ability, willingness and readiness to listen actively and reflect on advisee’s and advisor’s beliefs and values; these guide responses in advising practice and behavioural choices (Mozzon-McPherson 2017a). Whilst the ability to attend, empathize, reflect, confront and question may, consciously or unconsciously, be present in teachers or advisors, the intentional use of dialogue as a reflective tool to generate awareness, self-direction and self-determination in the learning process is fundamental in advising (Gremmo 2011). The concept of intentionality stresses an attribute of capability and decision-making from among a range of actions, and of choice of communicative skills able to generate reflection on alternatives and informed understanding of the selected pathway (Table 1).

McCarthy (2018) describes in detail the practices of a team of eight full-time learning advisors at a university in Japan with professional ALL experience ranging from three to five years. Her study noted that the advisors’ choice to emphasize specific words, themes, or topics influenced the direction of the verbal exchange and that advisors selected advising skills and strategies with a clear direction and purpose in mind; the degree to which they were able to connect their inner thoughts with purposes and actions determined their level of intentionality. During the advising process, advisors used a combination of macro skills (e.g. guiding, rapport building, initiating) and micro skills (e.g. attending, questioning, empathising). McCarthy observed that an awareness of their inner speech proved invaluable in helping advisors to understand their approach to external negotiations with learners and relate them to their own guiding beliefs, values, and behaviours. This self-awareness is fundamental for the professional development of advisors (see Section 5).

As research into advising broadens and deepens, so does the skills mapping. Table 2 summarises additional advising skills mentioned in various studies and extends from McCarthy’s study (2010). Some of these skills, such as clarification, are often a combination of macro and micro skills, whilst others integrate skills observed in use in counselling and coaching (Table 2).

The fundamental shift towards a sociocultural, socio-constructivist perspective of learning, and a person-centred emphasis on the psychology of learning, created the need to better understand the role of communicative and interpersonal skills in hindering or enhancing the learning process. This introduces socio-cultural competence which is the advisor’s ability to handle learning conversations effectively and sensitively: from establishing a good rapport with the learner to attending and understanding their needs and emotions, empathising with them, articulating, responding and negotiating their learning journey in adaptive and reflective ways. This competence necessitates self-regulation, intercultural understanding, and interpersonal knowledge and skills. Whilst self-regulation involves, among other aspects, the management of emotions (Tassinari 2016), intercultural understanding includes acquiring knowledge of, respect for, and the ability to interact comfortably with learners of varying cultural backgrounds. Lack of cultural awareness may lead to significant misunderstandings. This competence is necessary to establish clear rules of reciprocity, joint commitment, and trust.

This takes us to another competence, namely the personal and professional competence consisting of self-awareness and self-management. The former enables the advisor to recognize their own emotions and filters and their effects on themselves and others. The latter allows to manage such emotions, thoughts, and behaviours, organise these within a time-space continuum and communicate them with clarity and sensitivity. The development of this further competence contributes to building self-confidence and adaptability and to sharpening the intentional use of dialogical skills. If advising is a person-centred approach which takes into account the whole person and engages cognitive, meta-cognitive and affective strategies, this shifts the emphasis on training one’s mind to identifying learning needs, tasks, and problems as negotiated positive moments of personal growth as well and knowledge gain. If advising draws attention to emotions as important enablers or blockers in self-development and learning, this strengthens one’s ability to take control of one’s understanding of our surroundings and reactions to them (Mozzon-McPherson 2019: 101). If advising holds an explicit focus on awareness of the underpinning learner’s assumptions, values, and beliefs to understand one’s responses to specific problems and needs, this enhances the development of life-long and autonomous learning.

The fundamental role played by the quality of learning conversations emerges in the process of refining our understanding of the skills and competences of advising and, more specifically, the impact which intentional use of language as a pedagogic tool can have on the outcome of a learning conversation. Seeking guidance in other practices and, in particular, research into counselling therapy discourse (Ferrara 1994), Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP, Mozzon-McPherson 2017a), Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT, Curry 2014) and positive psychology (Mynard 2019) has allowed the advising practice to focus its attention on examining the quality of the dialogic exchange between advisor and advisee. Kelly (1996: 94) identified in the intentional use of dialogue a distinctive attribute of advising and central to transformative learning. Kelly (ibid.) stated that, although learner training programmes might directly, or indirectly, lead to this transformation, counselling usefully provides the framework to develop new ways of interacting with learners. It is through the careful co-construction of intentional reflective dialogue (IRD) (Kato & Mynard 2016) that we can see the interplay of macro and micro skills in action and their impact on the transformative learning experience of both learner and advisor. Dialogical competence completes, therefore, the professional know-how of advisors.

Hidden messages are given off from the very first moment a learner meets an advisor, even before one of the two speaks, so it is important that an advisor pays attention to:

1. The environment in which they meet: e.g. does it allow for undivided attention or are their distractions? These can be noises, interruptions (e.g. phone), furniture lay out (e.g. is the room messy, cold, etc.?). Whilst some distractions may continue to be present, it is useful to acknowledge them, accept them and embrace their presence to ensure they do not become a barrier. This also allows a learner to learn to scan their own environment (e.g. their study space and surroundings) and extend useful adjustment strategies beyond the advising session.

2. The quality of the opening conversation, which should be welcoming, paced, and tailored. Do we know in advance the learner’s name? Have they been there before? If so, have we looked through their records and know what they have been working on (signalling genuine concern)? The opening conversation helps set the tone of the session and builds the first steps for reciprocal trust and commitment.

3. The balance of questioning and listening, which form a significant part of the dialogic exchange. Questioning can take different forms and, depending on what type of questions we use, we can affect the direction of the conversation (Mozzon-McPherson 2019). Open questions invite extended replies which can provide additional information, while closed questions serve to accelerate fact finding and compel the advisee to make choices. Mozzon-McPherson (2017b) noticed, for example, a marked difference in responses when changing from WHY? and WHAT? into more HOW? questions. The latter provide a better opportunity to see the structure of the problem and engage with change, whilst WHY? questions and WHAT? reinforce the status quo (O’Connor & Seymour 1993).

Dialogue is always dynamic and co-constructed. Learners’ utterances represent their perspectives, beliefs, and values shaped by habits and behaviours learnt over time, expressed through forms of dialogue (or absence of) and filtered through emotions (Boudreau, MacIntyre, & Dewaele 2018). Advisors too have to ensure that they manage their own emotions, contradictions, values, and beliefs, and are sensitive to the learner’s viewpoint (Yasuda 2018). That is why it is important that an advisor is fully aware of the impact which a specific use of verbal and non-verbal language can have on the quality and progression of a learning conversation.

Specifically, ALL research (McCarthy 2018) highlights that a good advising session starts with active listening; this entails the advisor’s ability to observe, notice, feel, interpret, and reflect whilst listening to the advisee’s words. At times, this means performing the role of either a mirror or a ‘megaphone’, to amplify, reflect, or distort what has been said in an attempt to ensure co-construction of meaning and negotiate an agreed learning journey (Mozzon-McPherson 2019). The first step of any session is to observe, listen to and notice the argument/s presented by the learner with regard to a specific need and identify a possible starting point. This will then become the intention of the practice. In this balancing act the advisor needs to be able to suspend judgement and, instead, question in order to understand how best to support the learner and equip them with the skills to eventually self-regulate (Oxford 2017). This approach views the other’s needs (the learner’s needs in this case) as legitimate and authentic, and starts from the premise that the learner, who comes voluntarily to see an advisor, has expressed the intention to act in response to a need, a problem, or an interest.

Brockbank, McGill and Beech (2002) noted that an intentional dialogue is different from an ordinary dialogue in a way that existing values, beliefs, and ways of learning are challenged, and ‘taken-for-granted’ actions are questioned with the potential outcome of profound shifts and transformation in both advisors’ and learners’ world views. This kind of intentional dialogue is skilled work (Rogers 1951) which sites advising closer to counselling and psychology with the consequent effect that these dialogical skills needs to be noticed, learnt, and mindfully practised (Mozzon-McPherson 2017b). To do so, advisors need to record their sessions, log their reflections in action, and on action (Kato & Mynard 2016), and identify and qualify core attributes of successful advising discourse.

In the process of noticing, they also realise that communication is a complex and delicate act in which learning is a co-constructed experience at the end of which both parties emerge transformed. Mozzon-McPherson (2019) goes a step further in integrating knowledge from mindfulness practice as another useful enhancer of active listening and stating that mindful listening puts the advisor in a unique position to learn to suspend judgement and expectations and allows the advisee the time and space to express their complete trains of thoughts without interruption. How often have we caught ourselves already thinking of possible resources or advice after a few initial sentences from the advisee? By suspending judgement, mindful listening encourages advisees to feel heard, and to learn to hear themselves as they unpick their language learning problem. It helps to trace where the learner is ‘coming from’ – what purpose, interest, need, or emotion is motivating their ‘take’ in the conversation with the advisor. It also assists in clearly identifying how culturally and emotionally loaded some of the stances taken by the advisee or advisor are, and in accepting that both negative and positive emotions, moods, and attitudes have a place in the learning process (Yamashita 2015).

Empathy, for example, can contribute to reinforcing or creating a deeper understanding between advisor and advisee. Within dialogue it can be expressed through careful use of words aimed at reflecting the learner’s affective state in relation to the problem s/he is trying to address, and is asking advice about. This requires skilled use of pauses, repetition of words used by the advisee, able control of the tone of voice, sensibility at interpreting and mirroring body language, and negotiating turn-taking (Mozzon-McPherson 2017a; McCarthy 2010). The choice of language used in advising is therefore important for a successful cognitive, metacognitive, and affective meaning-making to occur. If advising language is inappropriate it can limit the depth and quality of reflection that learners are able to engage in (Yamashita & Kato 2012). Some research has highlighted the inadequacy felt by some advisors when faced with dealing with feelings and the emotional aspects of learning (Gremmo 1995; Tassinari & Ciekanski 2013), and the need for systematic targeted professional development in these aspects of language learning and advising competences.

From this brief analysis of the role of the use of intentional reflective dialogue in advising, it is clear that more research is needed both to map the dialogic skills engaged in ALL and to evaluate both how advising dialogue is effective in helping learners to succeed and why specific interventions are more conducive to reflection. To achieve this, we must continue to record and analyse advising sessions, learners’ and advisors’ reflective journals, track learners’ achievements in relation to performance as well as other stated improvements. Finally, we must start to generate a large database of audio and written transcripts to be utilized in advisors’ systematic, professional development.

A great number of advisors are and/or have been language teachers. This is due to factors such as institutional management in university language centres, the need to link self-access and classroom learning, the lack of specific educational programmes for advisors and, ultimately, a lack of a professional profile for language advisors. Although there is a lack of precise data, it would appear that for a considerable number of advisors their advising both follows from teaching and in many cases runs parallel to their teaching practice.

In recent years research has started to investigate which pathways teachers take to become advisors, what factors contribute to their professional development, who influences their transformation, and what are their turning points. Narrative and (auto) ethnographical research illustrate these unique journeys (see, among others, Morrison & Navarro 2012; Tassinari 2017; Šindelářová Skupeňová 2019; Howard et al. 2019). Among the recurring experiences mentioned by teachers while undertaking this transformation to advisor are:

— Experiencing the difference between the teacher and advisor role by, for example, “striking a balance between guiding and prescribing”; not planning the advising session and thinking one can cover everything like in a lesson plan, but rather letting the session flow (cf. Morrison & Navarro 2012: 355);

— Perceiving the challenge within this change of role (cf. Šindelářová Skupeňová 2019).

— Struggling with some of the micro-skills in the advising dialogue such as attending, questioning, confronting (Morrison & Navarro 2012: 356-357);

— Eye-opening experiences while practising some of the advising skills. Examples include asking open questions, asking challenging questions (what-if questions), using metaphors, and more in general, using intentional dialogue to enhance reflection (Howard et al. 2019);

— Redefining one’s beliefs and attitudes towards learning and teaching, and integrating these into one’s own teaching (Tassinari 2017: 330, Excerpt 11);

— Opening to the encounter with learners, accepting the learner’s perspective (Tassinari 2017: 324, Excerpt 3);

— Feeling how rewarding the experience of deeper insights into learners’ journeys;

— Witnessing learners’ transformation (see Güven-Yalçın ‘s quote in Howard et al. 2019: 325)

— Returning to teaching with a more flexible, learner-centred attitude (Tassinari 2017: 330, Excerpt 12).

If, on the one hand, it is often perceived as a challenge to leave ‘the teacher’ role with its higher degree of directiveness, guiding, providing materials, assigning tasks, and giving feedback, on the other hand the journey from teacher to advisor is mostly described as an extremely rewarding journey of self-discover, transformation, and self-advising. This is particularly evident in advisors’ reflective writing (see, among others, Yamamoto 2018). Among the eye-opening experiences are questioning one’s own beliefs on language teaching and learning and opening to others’ perspectives. This can be achieved through open, empathetic encounters and nurturing relationships with learners. Within the advising session, a crucial role is played by the advisor’s ability to ask reflective questions, and to let learners find their way towards transformation in their learning behaviour and beyond (Kato & Mynard 2016). This is evident in Šindelářová Skupeňová’s (2019) account of her professional development as an advisor. She describes the milestones of her journey as starting with “the innocent years of a teacher”, during which she basically used to conduct her advising sessions from a teacher’s perspective: giving tips, recommending resources, monitoring progress. In her second step, “the confused years”, she had to review her attitude after she encountered a learner for whom her usual tips and recommendations, her “usual procedure” did not work at all. Therefore, while admitting she did not know what could work for the learner, she asked him to reflect and make suggestions himself. For her this was a turning point away from a consolidated, teacher-directed process, towards a learner-centred, open dialogue. In the next stage, “the forming years”, she participated in professional development and peer-mentoring, learning to let go, to give students time to reflect, to ask reflective questions; afterwards she was able to enter in the stage “from advising to advising better”, thus in an ongoing self- and group reflection.

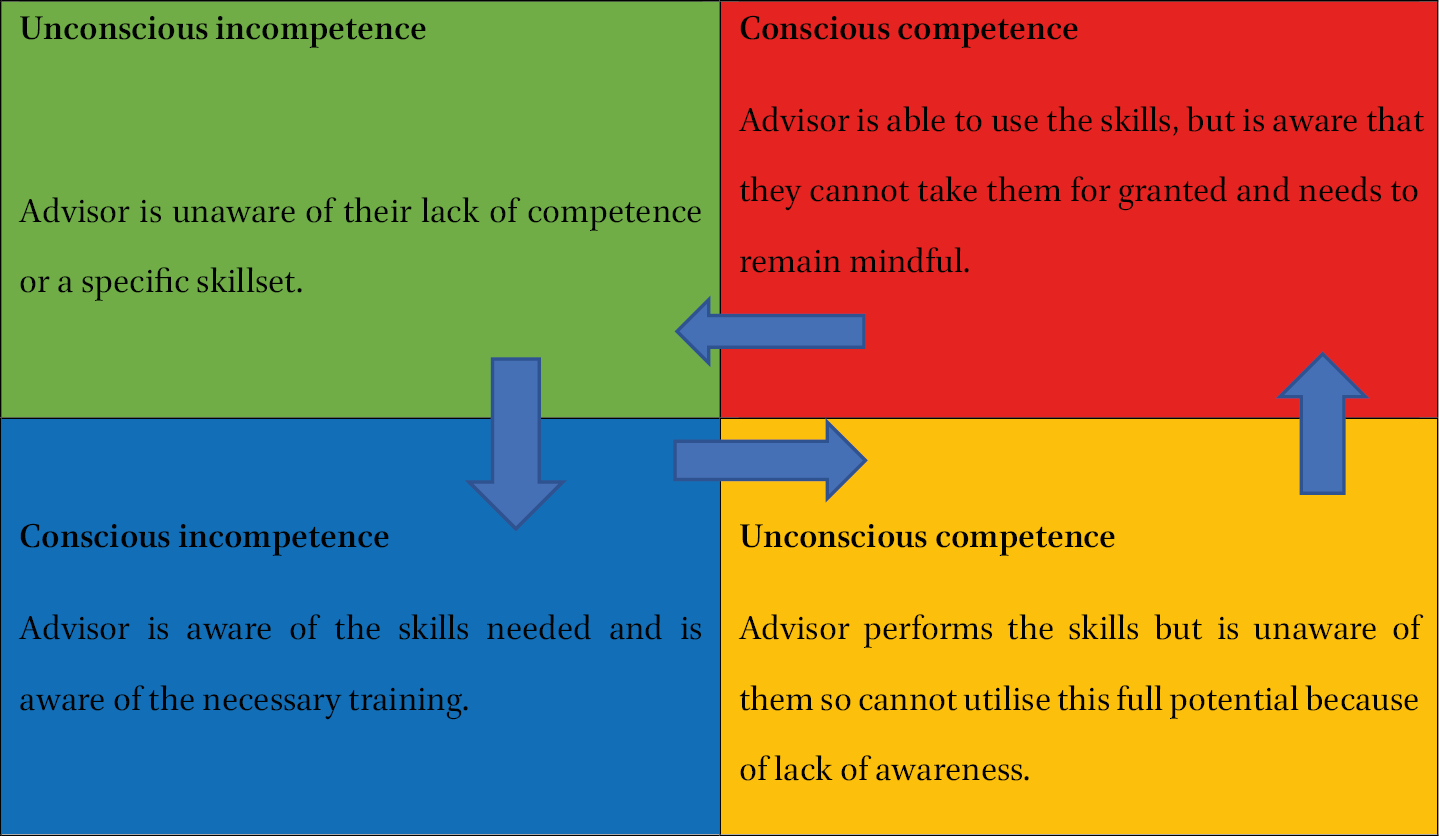

The professional development of advisors can be illustrated through a Four Stages Competence Model, adapted from “Four Stages for Learning Any New Skill”, as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 2. Competence model (Credited to: Gordon Training International by its employee Noel Burch in the 1970s).

At the beginning of one’s advising journey it is crucial to understand the differences between teaching and advising. The boundaries between these types of pedagogical relationships must be recognized in order to be able to fully embrace an open, empathic, non-judgemental approach to learners; as the practice of advising grows, it becomes easier to integrate some of the advising principles into one’s teaching, adapting these to classroom settings (Tassinari 2017). This process calls for new research, as Castro (2019) advocates. He became a language advisor as an undergraduate student, then joined a research project on advising without prior teaching experience, being thus able to reflects how deep this influenced his teaching:

I first became aware of advising in language learning when I was a freshman undergraduate student. At that time, as part of a learning project developed in a university course, advising was offered for language learners in situation of socioeconomic vulnerability. It turned out to be a very positive experience for me due to the feedback I received from the advisees with whom I worked. From this experience, I soon realized that language advising was a way of transforming learning trajectories as it empowered learners through a reflective dialogue. I then joined a research group that focused their efforts in fostering autonomy through language advising (see Magno e Silva 2017), but differently from my research fellows, I was first a language advisor before becoming a language teacher.

In the language classroom, I could not help but wonder how to integrate some advising skills (Kelly 1996) into my teaching practice. Besides my best efforts as a preservice language teacher, I struggled to reconcile these ideas with a strict syllabus that little fostered learner autonomy. I felt, however, that encouraging learner autonomy was part of my teacher identity and therefore could not avoid looking for opportunities for manoeuvers in my classroom. (Castro 2019: 404)

Although a growing literary corpus exists on how advising influences teaching practices in language teaching (Magno e Silva 2016; Tassinari 2017), helping them to gain more autonomy as teachers (Nonato 2014, quoted in Castro 2019) and/or strengthen pre-service language teachers’ L2 teacher self (Morhy 2018, quoted in Castro; Castro & Magno e Silva 2016; Castro 2018), more research in this field is needed (Castro 2019). Integrating advising training into teacher education may help to overcome the separation between these roles and move towards an “ultimate ideal scenario, […] a fluid continuum of the roles” (Tassinari 2017: 331, Excerpt 13).

This article has examined the role of advisors in its gradual, transformative, professional development and its initial distinctive separation from teaching. This started with the conscious choice of a different name (advisor/counsellor), the identification of a separate working space (self-access language centre) and the distinct awareness of new skills and competences observed, learnt and adapted from other disciplines and professional practices (e.g. psychology, counselling, coaching). What followed was the gradual establishment of a global community of practitioners with its own protocols, discourse, growing research and publications, identified professional development requirements and an increasing need for a qualification which could formally recognize their expertise.

Distinguishing advising from teaching was a significant, necessary step in this dynamic, professional journey. It contributed to consciously rejecting traditional paradigms and searching for new ones and the language to describe them. Having shaped its practice, and built advisors’ professional awareness and confidence, there is now a developing trend which recognizes the relevance and impactful role of skilful dialogic, learning conversations. The desire is to integrate some of the distinctive competences and skills of advising back into teaching and/or transfer them into other contexts such as online, academic advising, careers, student welfare and wellbeing.

The nature of ALL requires advisors to comfortably and confidently be in an ever-changing landscape of professional development (as illustrated in Figure 2) which is fundamentally driven by the very nature of its holistic person-centred view of learning and dialogue. This article has highlighted that expert advisors confidently move through these stages of unconscious and conscious competence, notice and try new learning landscapes and tools, and resourcefully balance their own wellbeing and that of their learners whilst pursuing specific learning objectives. This professional mindset and skillset will be crucial in the challenges which Higher Education is about to face globally in the post Covid-19 era in which confident acceptance of change and a mindful focus on co-construction of learning can provide a positive learning environment which prepares students to resourcefully manage uncertainty.

1 Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy (2nd ed.). Longman.

2 Borges, E. F. do, V., & Magno e Silva, W. (2019). The emergence of the additional language teacher/adviser under the complexity paradigm. DELTA: Documentação de Estudos Em Lingüística Teórica e Aplicada, 35(3). https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-460x2019350308

3 Boudreau, C., MacIntyre, P. D., & Dewaele, J.-M. (2018). Enjoyment and anxiety in second language communication: An idiodynamic approach. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 8(1), 149-70. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.1.7

4 Brockbank, A., McGill, I., & Beech, N. (2002). Reflective learning in practice. Gower Publishing.

5 Carette, E., & Castillo, D. (2004). Devenir conseiller: Quels changements pour l’enseignant? Mélanges CRAPEL, 27, 71-97.

6 Castro, E. (2018). Complex adaptive systems, language advising, and motivation: A longitudinal case study with a Brazilian student of English. System, 74, 138-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.03.004

7 Castro, E. (2019). Towards advising for language teaching: Expanding our understanding of language advising. Relay Journal, 2(2), 404-408. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020214

8 Castro, E., & Magno e Silva, W. (2016). O efeito do aconselhamento na trajetória de aprendizagem de uma estudante de inglês. In W. Magno e Silva & E. F. do V. Borges (Eds.), Complexidade em ambientes de ensino e aprendizagem de línguas adicionais (pp. 139-158). Editora CRV. https://doi.org/10.24824/978854441014.1

9 Ciekanski, M. (2007). Fostering learner autonomy: Power and reciprocity in the relationship between language learner and language learning adviser. Cambridge Journal of Education, 37(1), 111-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640601179442

10 Clemente, M. (2003). Learning cultures and counselling. Teacher/Learner interaction within a selfdirected learning scheme. In D. Palfreyman & R. Smith (Eds.), Learner autonomy across cultures (pp. 201-2019). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230504684_12

11 Cohen, A. (1998). Strategies in learning and using a second language. Longman.

12 Crabbe, D., Hoffmann, A., & Cotterall, S. (2001). Examining the discourse of learner advisory sessions. AILA Review, 15, 2-15.

13 Curry, N. (2014). Using CBT with anxious language learners: The potential role of the learning advisor. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(1), 29-41. https://doi.org/10.37237/050103

14 Dickinson, L. (1992). Learner autonomy 2: Learner training for language learning. Authentik.

15 Egan, G. (1998). The skilled helper: A problem management approach to helping (6th ed). Brooks Cole.

16 Ferrara, K. W. (1994). Therapeutic ways with words. Oxford University Press.

17 Gray. D. (2007). Towards a systemic model of coaching supervision: Some lessons from psychotherapeutic and counselling models. Australian Psychologist, 42(4), 300-309. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060701648191

18 Gremmo, M.-J. (1995). Conseiller n’est pas enseigner: Le rôle du conseiller dans l’entretien de conseil. Mélanges CRAPEL, 22, 33-62.

19 Gremmo, M-J. (2009). Advising for language learning: Interactive characteristics and negotiation procedures. In F. Kjisik, P. Voller, N. Aoki & Y. Nakata (Eds.), Mapping the terrain of leaner autonomy (pp. 145-167). Tampere University Press.

20 Gremmo, M.-J. (2011). Advising for language learning: A negociative process. In N. Aoki & Y. Nakata (Eds.), Gakushuusha autonomy: Hajimete no hito no tame no introduction [Learner autonomy: A beginner’s Introduction]. Hitsuji Shobo Editions.

21 Güven-Yalçın, G., Howard, S. L., & Karaaslan, H. (2019). Journey to the advisor within: Exploring challenge, transformation and evolution in advisor stories. Relay Journal, 2(2) 319-322. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020207

22 Howard, S. L., Güven-Yalçın, G., Karaaslan, H., Atcan Altan, N., & Esen, M. (2019). Transformative self-discovery: Reflections on the transformative journey of becoming an advisor. Relay Journal, 2(2) 323-332. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020208

23 Karlsson, L. Kjisik, F., & Nordlund, J. (1997). From here to autonomy. Helsinki University Press.

24 Kato, S. (2012). Professional development for learning advisors: Facilitating the intentional reflective dialogue. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 74-92. https://doi.org/10.37237/030106

25 Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

26 Kato, S., & Sugawara, H. (2009). Action-oriented language learning advising: A new approach to promote independent language learning. The Journal of Kanda University of International Studies, (21), 455-475.

27 Kelly, R., (1996). Language counselling for learner autonomy: The skilled helper in self-access language learning. In R. Pemberton, E. Li, W. Or & H. Pierson (Eds.), Taking control: Autonomy in language learning (pp. 93-113). Hong Kong University Press.

28 Lamb, T. (2000). Finding a voice - learner autonomy and teacher education in an urban context. In B. Sinclair, I. McGrath and T. Lamb (Eds.), Learner autonomy, teacher autonomy: Future directions (pp. 118-127). Longman.

29 Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2007). Sociocultural theory and second language learning. In B. Van Patten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories of second language acquisition: An introduction (pp. 201-223). Lawrence Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429503986-10

30 Little, D. (2007). Language learner autonomy: some fundamental considerations revisited. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1): 14-29. https://doi.org/10.2167/illt040.0

31 Ludwig, C. & Mynard, J. (Eds.) (2012). Autonomy in language learning: Advising in action. IATEFL.

32 Magno e Silva, W. (2016). Conselheiros linguageiros como potenciais perturbadores de suas próprias trajetórias no sistema de aprendizagem. In W. Magno e Silva & E. F. do V. Borges (Eds.), Complexidade em ambientes de ensino eaprendizagem de línguas adicionais (pp. 199–221). CRV. https://doi.org/10.24824/978854441014.1

33 Magno e Silva, W. (2017). The role of self-access centers in foreign language learners autonomization. In C. Nicolaides & W. Magno e Silva (Eds.), Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics and learner autonomy (pp. 183-208). Pontes.

34 McCarthy, T. (2010). Breaking down the dialogue: Building a framework of advising discourse. Studies in Linguistics and Language Teaching, 21, 39-79.

35 McCarthy, T. (2018). Exploring inner speech as a psycho-educational resource for language learning advisors. Applied Linguistics, 39(2), 159-187.

36 Morhy, S. S. (2015). A influência do aconselhamento linguageiro na trajetória de uma aluna de Letras-Inglês. Universidade Federal do Pará.

37 Morrison, B. R., & Navarro, D. (2012). Shifting roles: From language teachers to learning advisors. System, 40, 349-359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2012.07.004

38 Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2012). The skills of counseling: Language as a pedagogic tool. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 43-64). Pearson Education.

39 Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2017a). Considerations on the role of mindful listening in advising for language learning. Zeitschrift für Fremdsprachenforschung, 28(2), 159-179.

40 Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2017b). Reflective dialogues in advising for language learning in a neuro-linguistic programming perspective. In C. Nicolaides & W. Magno e Silva (Eds.), Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics and learner autonomy (pp. 153-68). Pontes.

41 Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2019). Mindfulness and advising in language learning: An alternative theoretical perspective. Mélanges CRAPEL, (40), 88-113.

42 Mozzon-McPherson, M., & Vismans, R. (2001). Beyond language teaching towards language advising. CILT.

43 Mynard J. (2019). Self-access learning and advising: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan & S. Nakamura (Eds.), Innovation in Language Teaching and Learning. New Language Learning and Teaching Environments. The case of Japan (pp. 185-210). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12567-7_10

44 Mynard, J., & Carson, L. (Eds.) (2012). Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context. Pearson Education.

45 Nonato, R. S. (2014). O aconselhamento linguageiro como forma de intervenção e formação docente. Universidade Federal do Pará.

46 O‘Connor, J., & Seymour, J. (1993). Introducing Neuro-Linguistic Programming (revised ed). Aquarian/Thorsons.

47 Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Newbury House/Harper and Row.

48 Oxford, R. L. (2017). Teaching and researching language learning strategies. Self-regulation in context. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315719146

49 Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centred therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory. Houghton Mifflin.

50 Rubin, J. (2007). Language counselling. System, 35(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.11.001

51 Rutson-Griffiths, Y., & Porter, M. (2016). Advising in language learning: Confirmation requests for successful advice giving. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(3), 260-286. https://doi.org/10.37237/070303

52 Shelton-Strong, S. (2020). Advising in language learning and the support of learners’ basic psychological needs: A self-determination theory perspective. Language Teaching Research, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820912355

53 Šindelářová Skupeňová, M. (2019). Reflections of an advisor: a never-ending story. Mélanges CRAPEL, 40(1).

54 Spänkuch, E. (2014). Systemisch-konstruktivistisches Sprachlern-Coaching. In A. Berndt & R.-U. Deutschmann (Eds), Sprachlernberatung – Sprachlerncoaching (pp.51-81). Peter Lang.

55 Spänkuch, E., & Kleppin, K. (2014). Support für Fremdsprachenlerner. Sprachlerncoaching als Konzept und Herausforderung. Jahrbuch Deutsch als Fremdsprache. Intercultural German Studies, 40, 189-213.

56 Tassinari, M. G. (2016). Emotions and feelings in language advising discourse. In C. Gkonou, D. Tatzl & S. Mercer (Eds.), New directions in language learning psychology (pp. 71-96). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23491-5_6

57 Tassinari, M. G. (2017). How language advisors perceive themselves: Exploring a new role through narratives. In C. Nicolaides & W. Magno e Silva (Eds.), Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics and learner autonomy (pp. 305-336). Pontes.

58 Tassinari, M. G., & Ciekanski, M., (2013). Accessing the self in self-access learning: Emotions and feelings in language advising. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(4), 262-280. https://doi.org/10.37237/040404

59 Whittington, J. (2016). Systemic coaching and constellations: An introduction to the principles, practices and application (2nd ed). Kogan.

60 Yamamoto, K. (2018). The journey of ‘becoming’ a learning advisor: A reflection on my first-year experience. Relay Journal, 1(1), 108-112. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010110

61 Yamashita, H. (2015). Affect and the development of learner autonomy through advising. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(1), 62-85. https://doi.org/10.37237/060105

62 Yamashita, H., & Kato, S. (2012). The Wheel of Language Learning: A tool to facilitate learner awareness, reflection and action. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 164-169). Pearson Education.

63 Yasuda, T. (2018). Psychological expertise required for advising in language learning: Theories and practical skills for Japanese EFL learners’ trait anxiety and perfectionism. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(1), 11-32. https://doi.org/10.37237/090103